The History of the Economy of Southern Kyrgyz in the 19th Century

In the history of the economy of southern Kyrgyzstan, the 19th century was a turning point: they began to transition from the main form of economy—animal husbandry—to agriculture. This process had been partially observed earlier, but in the 19th century, it took on a more intensive character. The degree of development and spread of agriculture was determined by socio-economic factors, although it also significantly depended on natural and geographical conditions, which influenced the types of economies.

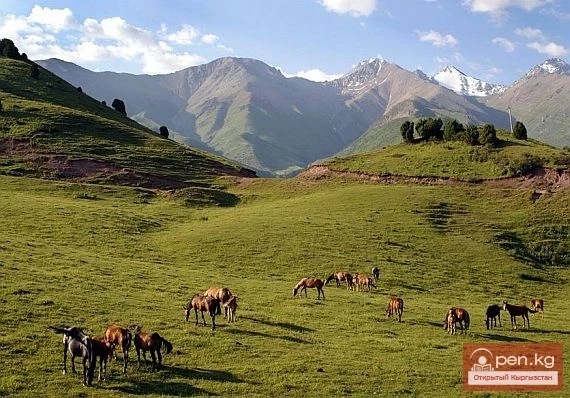

The nature of the southern part of the Osh region is rich and diverse. Its relief, formed by the mountain ranges of Pamir-Alai and Tien Shan, includes the southern part of the vast Fergana Valley. High mountains, covered with eternal snows and rich in tree, shrub, or herbaceous vegetation, are combined with ridges, intermountain high plateaus, narrow gorges, and spacious fertile valleys. From ancient times, two types of economies have developed here: pasture-animal husbandry and agriculture.

In the Alai region (as well as in the basin of the ALAIKU River), transhumant-pastoral animal husbandry predominated, facilitated by the presence of excellent natural pastures. The picturesque Alai Valley, located at an altitude of 3000-3200 m above sea level between the Alai and Zaalai mountain ranges, has long attracted nomads with its lush vegetation, which has high nutritional qualities. To this day, it is renowned as the largest area for transhumant-pastoral animal husbandry and has inter-republican significance, similar to Suusamyr in northern Kyrgyzstan. Agriculture in the Alai region was supplementary, and bread was mostly imported. Agriculture developed in the basins of the Kara-Kuldja and Tar rivers. The natural conditions of this area are favorable for both agriculture and animal husbandry.

In other places, alongside irrigated agriculture (in the valleys of the Kok-Suu, Isfara, Sukh, and Laylak rivers), rain-fed agriculture was also being developed: houses were being established. At the same time, in the mountainous parts of these regions, the natural conditions favored the preservation of pastoral economies.

It is characteristic that of the total area used for various crops, two-thirds were under rain-fed lands and only one-third under irrigated lands.

Although by the early 20th century, agriculture had already taken firm positions, the transition to it was not always associated with a break from animal husbandry. Due to deep traditions, animal husbandry continued to occupy a prominent place in Kyrgyz economy, but centuries-old nomadic skills and pastoral economies gradually gave way to settled, agricultural ones.

At that time, nomadic herding with livestock grazing in summer, autumn, and winter pastures was still based on a communal-tribal principle. In large common pastures, a specific territory was assigned to each community or group of ails.

Kyrgyz people raised sheep, goats, horses, camels, and cattle. The leading branch of animal husbandry was sheep breeding. The sheep were predominantly of the Kyrgyz breed with fat tails, known for their great endurance and high meat yield, though they had coarse wool. In the southwestern regions, they raised Hissar breed sheep (ysar koy). Goat breeding developed significantly here compared to other regions.

They preferred two-humped camels. In 1913, their numbers were already low, and they were primarily owned by wealthy households. In the western regions, there were significantly fewer camels than in the eastern ones, which is likely explained by the longer preservation of nomadic traditions in the latter.

Cows were kept everywhere. Dairy products were used for family needs. Bulls served as draft power in agricultural economies. In Alai (as well as in Eastern Pamir), yaks were raised, valued not only for their high-quality dairy products but also as indispensable pack animals well adapted to high-altitude conditions.

Horses were mainly of the Kyrgyz breed, widely used not only for riding (and for packing) but also for obtaining kumys. In the western regions, donkeys were used in households.

Among the cultivated agricultural crops, spring wheat and barley occupied the main place, with the latter being predominantly grown in high-altitude areas. They also sowed millet in the past, but, according to the elders, its sowing has gradually decreased. Corn was mainly sown in the northeastern and western regions. In these same regions, rice was cultivated. In the west, Kyrgyz people sowed jujube (a type of sorghum).

By the early 20th century, southern Kyrgyz people had mastered cotton as a technical crop, and melons and watermelons as garden crops.

Under the influence of neighboring settled agricultural populations, small gardens appeared among the Kyrgyz (mainly in the southwestern regions), where they grew onions, carrots, and herbs. In household plots, at the beginning of the 20th century, some households began to plant fruit trees and vineyards. In the households of large beys and feudal nobility, apricot trees (uruk) were grown on large areas.

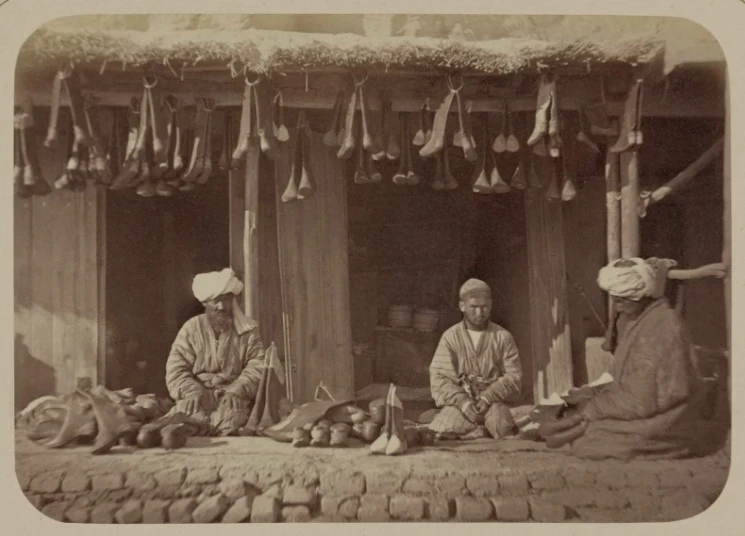

Despite the introduction of new crops into economic circulation, land cultivation and harvest were carried out with the most primitive tools. The universal tool was the ketmen (hoe). They plowed with a wooden plow (omach) with an iron tip. Only in certain areas of the northeastern part of the region, under the influence of Russians, did the plow appear. They harvested crops with sickles (orok). Grain was threshed with the help of horses and bulls. For transporting hay and harvest from rain-fed lands in mountainous areas, they used a sled (chiyne). In the western part of the Alai Valley, in addition, sleds borrowed from Tajiks (chigina) were used.

As everywhere among the Kyrgyz, hunting occupied a certain place in the economy. They hunted wild animals with flintlock guns.

Read also:

The 19th Century — A Century of Radical Change in the Lives of the Kyrgyz

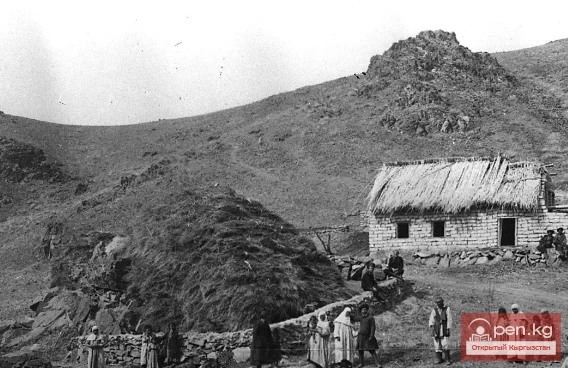

Settlements and Permanent Housing The 19th century was a turning point in the life of the Kyrgyz....

The title translates to "Dwellings of the Kyrgyz."

SETTLEMENT AND DWELLING The presence of two different types of economic activities in the 19th and...

Aliens from the Flat Ferghana

The First Settlers Southwestern Fergana is a mountainous area that is part of the Turkestan Range...

Natural Regions and Occupations of the Population of Kyrgyzstan

The Population of Kyrgyzstan in the 19th - Early 20th Century Most of the country's territory...

Agriculture of the Southern Kyrgyz in the 19th - Early 20th Centuries.

The second half of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century were filled with...

Ethnic History of the Southern Kyrgyz Tribes

The territory of the Osh region occupies the southwestern part of Kyrgyzstan. Its area is 75.5...

Conclusions on the Study of the Settled Dwellings of the Southern Kyrgyz

The study of the sedentary dwellings of the southern Kyrgyz allows us to draw some conclusions....

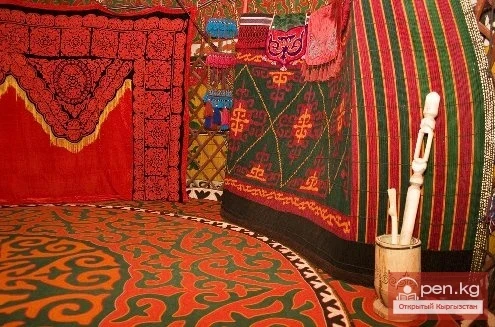

Felt Wall Carpets "Tush Kiyiz"

An interesting fact is the existence of felt wall carpets called 'tush kiyiz' (also...

Localization of the Tribal Groups of the Kyrgyz

Localization of the tribal groups of Kyrgyz...

Southern Kyrgyz Embroidery

Embroidery of the Southern Kyrgyz Southern Kyrgyz embroidery is the result of centuries of...

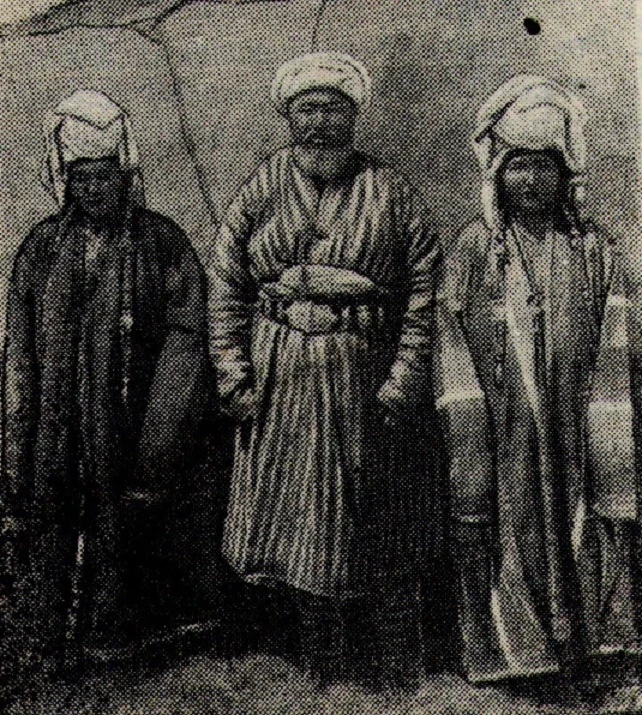

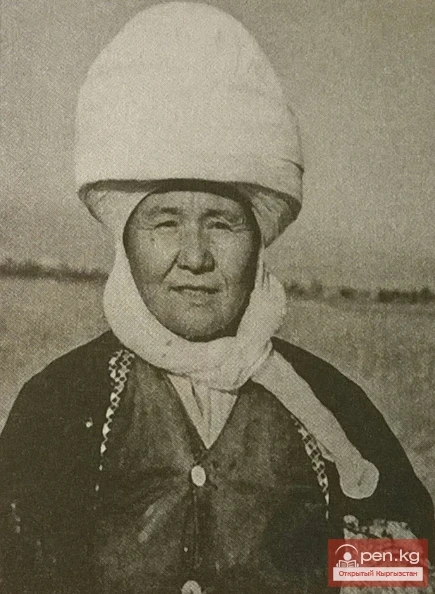

Clothing of the Southern Kyrgyz. Part - 1

The clothing of the southern Kyrgyz has not received special attention in literature. There are...

The Ethnonym "Kyrgyz"

For a proper understanding of the ethnic processes that led to the formation of the Kyrgyz...

Weaving

Among other domestic crafts, weaving held one of the primary places among the Kyrgyz in the past....

The Unknown Country of Kyrgyzstan

In Central Asia lies an amazing mountainous region, intersected by the powerful ridges of the Tien...

Agriculture among the Kyrgyz

AGRICULTURE Agriculture was an important area of economic activity for the Kyrgyz, ranking second...

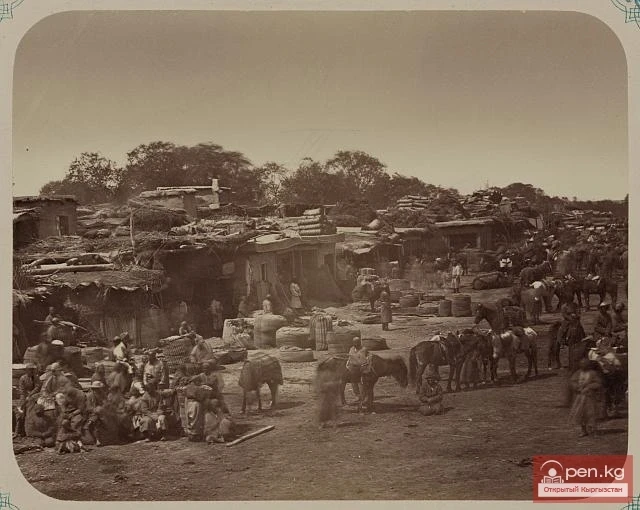

Osh. Population

Growth of the Population of Osh “Although the colonial path of development that Central Asia took...

Clothing of the Southern Kyrgyz. Part - 2

Among the ready-made items purchased by Kyrgyz people, in addition to light robes, were quilted...

In the Kyrgyz Republic, the yield of certain crops in 2025 decreased due to a lack of irrigation water, - Ministry of Economy

- In the first nine months of 2025, the gross agricultural output of the country reached 348.4...

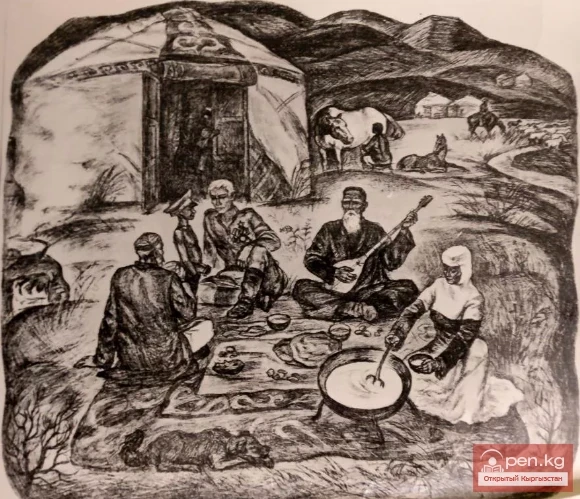

The Culture of Nutrition Among the Kyrgyz Has a Deep History

The food culture of the Kyrgyz has a deep history. The formation of its main ethno-cultural...

Cattle Breeding Among the Kyrgyz in the 20th to Early 21st Century

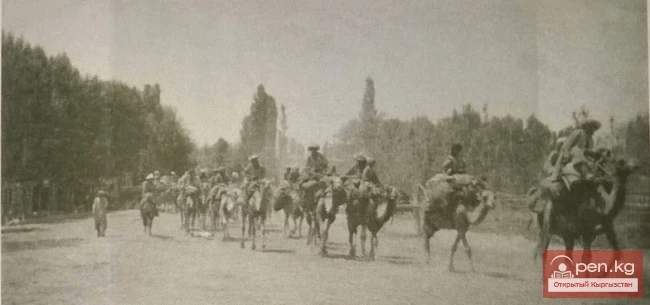

Migration near the village of Troitskoye. Kara-Kyrgyz. Syrdarya region. 1902. Animal Husbandry in...

Kydyrmaev Adashbek

Kydyrmaev Adashbek (1943), Doctor of Agricultural Sciences (2001) Kyrgyz. Born in the village of...

The Spread of Kyrgyz Pile Weaving

Pile weaving has long been known to the Kyrgyz living in the territory of the modern Osh region,...

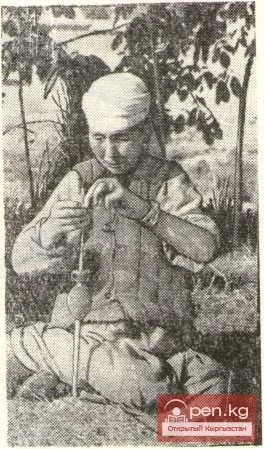

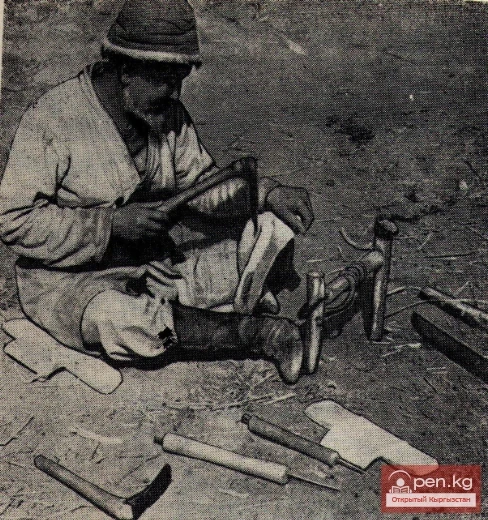

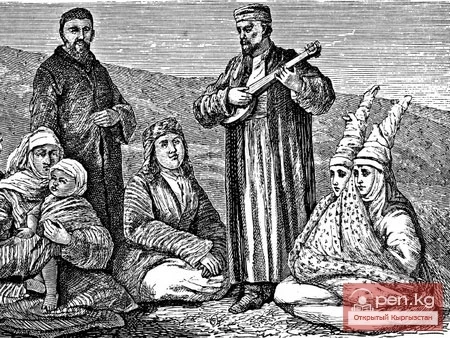

Production of Musical Instruments and Saddles by Kyrgyz People

Kyrgyz Woodworking Masters Woodworking masters also make musical instruments (Fig. 84) from...

Quality testing of food wheat has begun at the Ministry of Agriculture and Melioration of Kyrgyzstan.

The Grain Expertise Center of the Ministry of Agriculture and Melioration of the Kyrgyz Republic...

Agriculture, Forestry, and Fishing

The gross output of agricultural products, forestry, and fishing in January-June 2014 amounted to...

What types of climate are found in Kyrgyzstan?

The Climate of Mountainous Kyrgyzstan The climatic conditions of the country are determined by the...

Lyashenko Ivan Vasilyevich

Lyashenko Ivan Vasilievich (1906-1983), Doctor of Economic Sciences (1972), Professor (1974)...

Felt Clothing of the Kyrgyz - Kementai

Among the herders in northern Kyrgyzstan, felt clothing in the form of a kementai cloak was...

The Economy of the Kyrgyz in the VI—XVIII Centuries

The economy of Kyrgyzstan during the era of Turkic states experienced syncretic development (a...

The Economy of the Kyrgyz from Ancient Times to the 6th Century

The tribal communities inhabiting the Central Tien Shan, Issyk-Kul, Chui, and Talas valleys...

Agriculture, Land Resources of Kyrgyzstan

Land Resources of Kyrgyzstan The climatic features dictate the development of agricultural sectors...

Cattle-Breeding and Agricultural Economy of the Ussurians

Idealization of Nomads in Ancient Greek Literature In ancient Greek literature, there is a clear...

Embroidery - a widespread form of Kyrgyz folk art in the past

Embroidery Embroidery is one of the most widespread forms of Kyrgyz folk art in the past. The...

Cattle Breeding among the Kyrgyz

Migration in the Alai Range. Early 20th century. Kyrgyz SSR HERDING The leading sector of the...

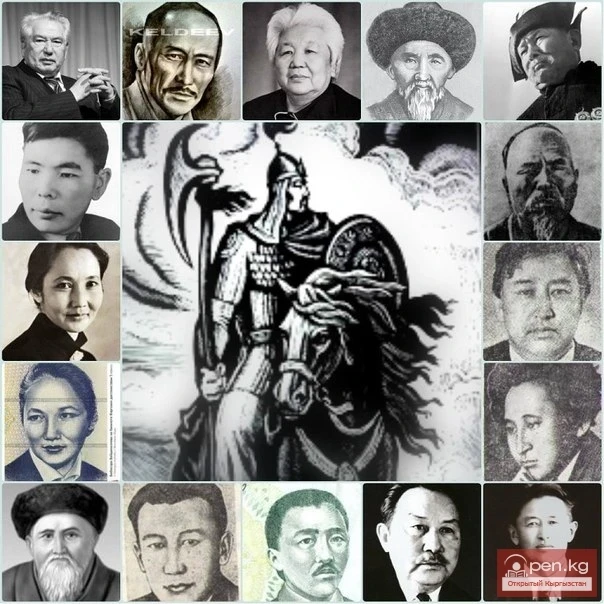

Ethnic History of the Kyrgyz People

History of the Origin of the Kyrgyz People The problem of the origin of the Kyrgyz people is one...

Formation and Development of the National Costume of the Kyrgyz People

National Clothing and Costumes of the Kyrgyz The formation and development of the national costume...

Baking Bread Among Different Territorial Groups of Kyrgyz People

Bread and Bread Products. Bread baking was most widespread in the southern regions and also in...

Worldview Concepts of the Surrounding World

Most geographical names in Kyrgyzstan have local etymology. The origin of several toponyms is...

Kokshaal-Too and Peak Dankov

Remoteness, wildness, and mystery are the concepts that characterize and give an idea of this...

The Prolonged Process of the Kyrgyz Transition from Nomadism to Agriculture

Land Conflicts Conflicts over land frequently occurred between the nomadic Kyrgyz and the settled...

Attractions of the City of Osh

Osh - one of the oldest cities in Central Asia, located on the southeastern edge of the Fergana...

The Atbashi Ridge

Atbash The mountain range belongs to the southern arc of the Inner Tien Shan in Kyrgyzstan. It...

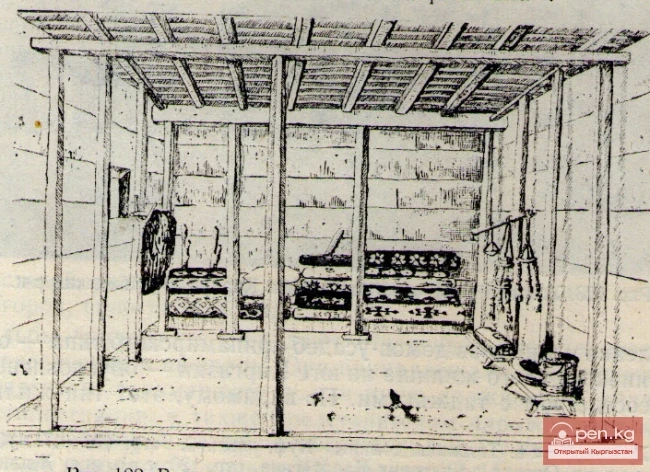

Interior Design of a Pamir-Type House

In the early 20th century, Kyrgyz people also built houses similar to the described type, but...

Fergana Range

Fergana Ridge A mountain range in the Tien Shan that stretches from southeast to northwest,...

Resolution on Economic and Cultural Construction and Prospects for the Development of the Kirghiz ASSR

Resolution of the Council of People's Commissars of the RSFSR On May 31, 1930 (i.e., at the...

A.N. BERNSTEIN - Researcher of Ancient Cultures of Central Asia. Part - 3

The Brilliant Insights of the Talented Scholar - Alexander Natanovich Bernstein In his work...

Oruzbaev Asangaliy Umurzakovich

Oruzbaev Asangaliy Umurzakovich (1930), Doctor of Economic Sciences (1974), Professor (1975),...