Kyrgyz Woodworking Masters

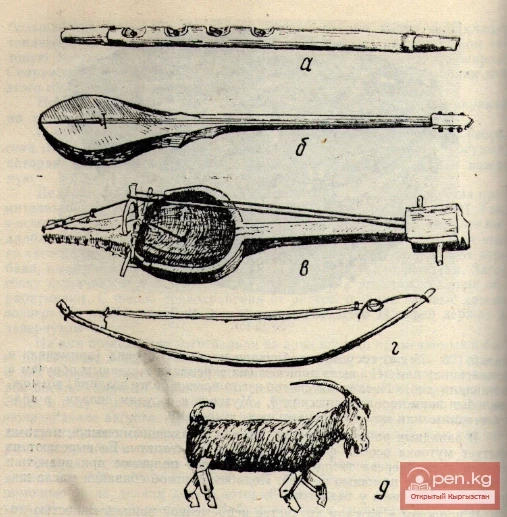

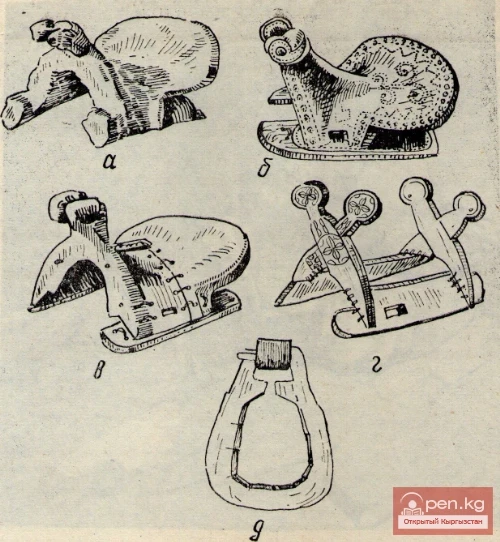

Woodworking masters also make musical instruments (Fig. 84) from juniper and apricot wood.

The southern Kyrgyz string instrument (komuz) is essentially identical to that made by Kyrgyz masters in the north. There are many variations in the length of the neck and the degree of flattening of the resonator.

In the past, ancient Kyrgyz musical instruments such as the bowed kyiak (also called kyzhak) and the flute choor were made in the south. Now, the youth do not play them. The elderly are forgetting them as well. Masters no longer make the widely popular entertainment goat tak teke, which was activated while playing the “komuz”.

Saddles of Andijan type with a bifurcated head at the high front bow are produced everywhere in the region (Fig. 85).

The production of saddles for sale was particularly developed in the eastern part of the Osh region, in the Uzgen and Soviet districts. Here, in some villages, there were up to ten or more specialists.

The masters we observed make saddle bows from a single piece of wood as well as composite ones.

Separate parts are joined with rawhide straps (kyok). Holes are drilled using a primitive drill, widely used by woodworking masters (Fig. 86, 88).

The finished saddle bow is covered with camel skin, which is secured with small nails in such a way that they create a pattern (Fig. 85, b).

Some wooden items were traditionally decorated with painting and carving. Painting is most characteristic for the “dzhavan” cabinet. Its front side is covered with a multicolored pattern that includes a wide variety of motifs. This technique is not typical for the Kyrgyz and, most likely, like the “dzhavan” itself, was borrowed from the Uzbeks.

Flat-relief wood carving is characteristic of the Kyrgyz. We notice it on the cases for bowls, which have survived in many homes in southern Kyrgyzstan. The ornament is large, has rounded lines, and the typical motif of a spiral predominates. The tools for carving included chisels, a gouge, a wooden hammer, a mallet, and a knife with a curved blade.

The carving that decorates the front side of the stands for “dzhuk” — “sekichik” — has a different character. It is primitive. The ornament is cut along the contour with a sharp knife. The pattern is simple: in the form of nets, diagonal crosses, four-, six-, and eight-petaled rosettes. In terms of the character of the pattern and the technique of execution, there is a complete analogy with the carving on the door frames of the yurt.

We did not encounter masters skilled in applying patterns to wooden products in southern Kyrgyzstan. Apparently, after the Kyrgyz transitioned to a sedentary lifestyle, the art of carving began to decline without further development.

A comparison of woodworking techniques and the range of products among southern and northern Kyrgyz leads to the conclusion that despite some peculiarities observed among southern Kyrgyz, this type of material production has uniform forms among all groups of Kyrgyz and undoubtedly dates back to very ancient times: This is evidenced by archaeological finds on the territory of modern Kyrgyzstan and Altai.

In our time, woodworking in rural areas has taken a different direction and is carried out at completely different organizational levels. In collective farm workshops, carpenters and joiners often have specialized training. Their work is largely mechanized, with the use of jigs and modern tools. The workshops serve the production needs of the collective farms, where they also produce accessories for wheeled transport, construction parts for collective farmers' houses (frames, doors, etc.), furniture, and some household items that correspond to the national lines of the Kyrgyz population.

The production of wooden vessels by the Kyrgyz