Idealization of Nomads in Ancient Greek Literature

In ancient Greek literature, there is a clear idealization of nomads. The goal: to improve Greek society. The method of improvement: a return to the lifestyle of heroic ancestors. For clarity, the morals of those raised in the harsh and free natural conditions of "barbarian" steppe life were contrasted with the refined and corrupted morals in Greek city-states. This idealization reached its peak in the biography of the Scythian prince Anacharsis, son of King Gnurus and uncle of King Idanthyrsus, who defeated the hordes of the Persian king Darius (514 BC). It is characteristic that in the 18th century, the image of the same Anacharsis was used by Rousseau and writers of his circle for public condemnation of the unbridled luxury and extravagance of the French court and the aristocracy that imitated it.

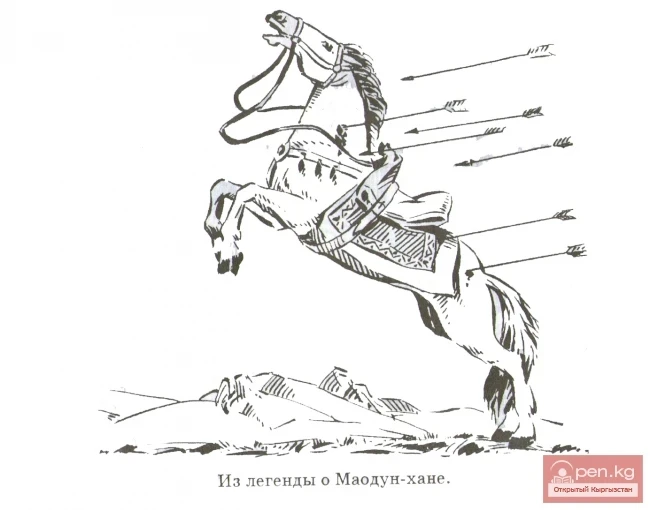

In Central Asia, idealization was not in vogue. Here lived "realists." And if the Han Chinese officially preached nomadophobia, then the northern "barbarians" were raised in the same spirit towards the Han. It is telling, for example, that the Avar (Juan-Juan) princess, who married the Chinese emperor, surrounded herself with a large group of her tribesmen, who behaved boldly and provocatively at court.

The "steppe Amazon," upon becoming empress, became famous only for never having spoken a word of Chinese in her life.

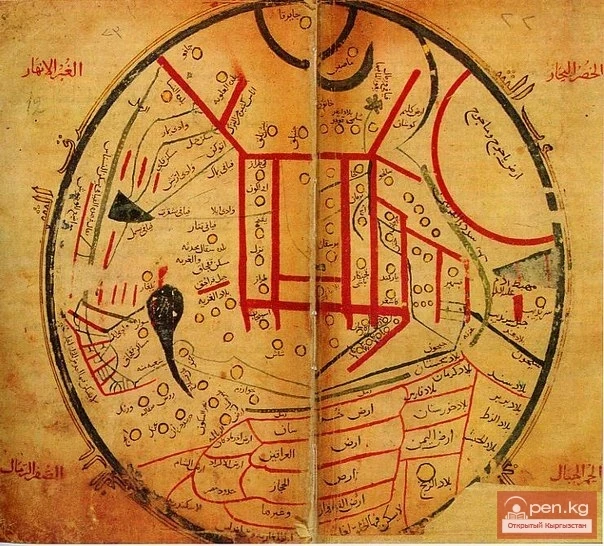

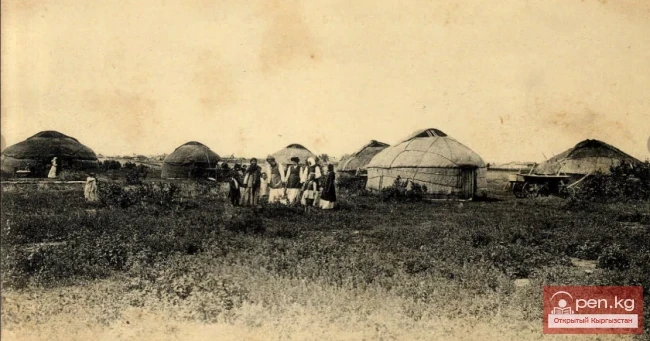

However, both "idealists" and "realists" unanimously, albeit for different reasons, highlighted only one side of the complex economy of their neighbors — nomadic cattle breeding. Information about other sectors of labor activity is rare and vague. Thus, in the Chinese dynastic chronicles, the formula "roaming in search of grass and water" became a cliché for characterizing the economic activities of all steppe peoples from ancient times to the 19th century inclusive. Other occupations, according to the chroniclers, were not worth mentioning.

Even serious historians of the 19th and 20th centuries did not always critically perceive the multiple and unambiguous information from ancient authors about nomadic cattle breeding as the only type of economy of the steppe dwellers in antiquity.

Hence the economic-demographic calculations that dictated incorrect political conclusions.

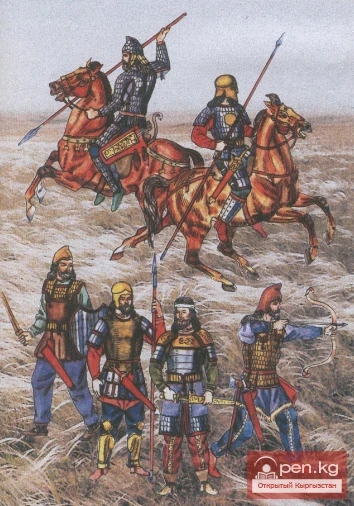

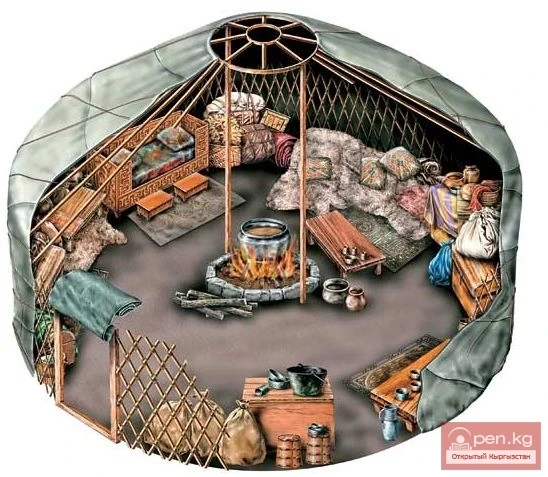

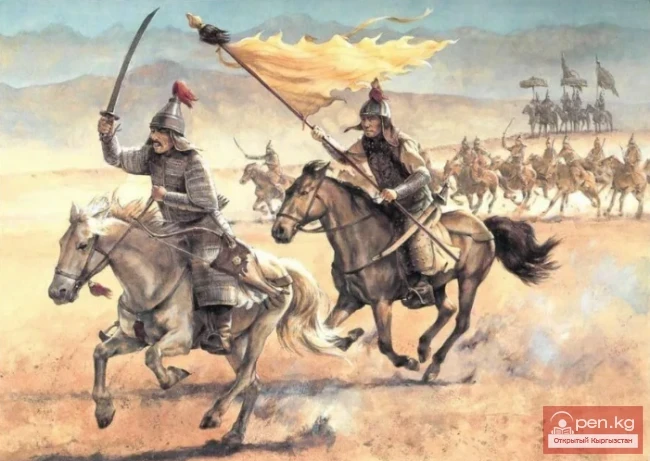

Indeed, these historians wrote, for grazing livestock, no matter how many there were, there is no need for a large number of herders. This means that a large number of the population, free from active labor, concentrated in ails, which could easily be assembled into mounted detachments for raids on neighbors. The object of the nomads' attacks was not so much the steppe dwellers, who had nothing to take besides livestock and who, as a rule, could stand up for themselves, but the cities and settlements of farmers. Here, behind clay walls (not such an insurmountable barrier), were the grains, fabrics, high-quality metal products, precious ornaments, and, finally, people who did not possess the martial skills of a steppe dweller. These people could be captured and then sold into slavery.

So, wolves — steppe dwellers, and sheep — farmers. From here it is not far to the harmful and incorrect theory of the "eternal, irreconcilable enmity" between the steppe and oases, between cattle breeders and farmers, leading to a division into civilized and wild, historical and non-historical peoples.

In reality, everything is not so simple and unambiguous. Thanks to the work of archaeologists in the Black Sea region, Kazakhstan, and Central Asia, both large and small settlements of ancient cattle breeders have been discovered, indicating the development of agriculture and crafts among them.

Settlements from the Usun period have also been found within the Semirechye region, including the northern areas of Kyrgyzstan. However, even before the discovery of these settlements, some scholars, based on the materials from the excavations of Usun burial mounds, expressed reasonable doubts that the Usuns were exclusively engaged in nomadic cattle breeding. M. V. Voievodsky and M. P. Gryaznov in 1928-1929 excavated a number of Usun burial mounds in the vicinity of the cities of Tokmak and Przhevalsk (Karakol). In the burials, grain grinders, charred wheat grains, millet husks, and a large quantity of fragile and heavy ceramic dishes unsuitable for frequent transportation were found.

From this, the conclusion follows: the economy of the Usuns was cattle-breeding and agricultural, with a leading role for cattle breeding.

Over time, this conclusion was agreed upon by almost all archaeologists, but they noted that it does not stem from the excavation materials, but was only a correct theoretical assumption. Indeed, what do the findings of grain remains indicate? Only that it was consumed as food, and not a word about how it was obtained. The Usuns could have grown the grain themselves, but they could also have exchanged it for livestock or products of cattle breeding in the agricultural regions of Fergana or, for example, Eastern Turkestan, with which they had close political ties. What does the discovery of a grain grinder indicate? Exclusively that the grain obtained by unknown means was turned into flour and groats.

Descriptions of the Saka and Scythians by Ancient Greek Authors