Saka and Scythians through the Eyes of Cherilus

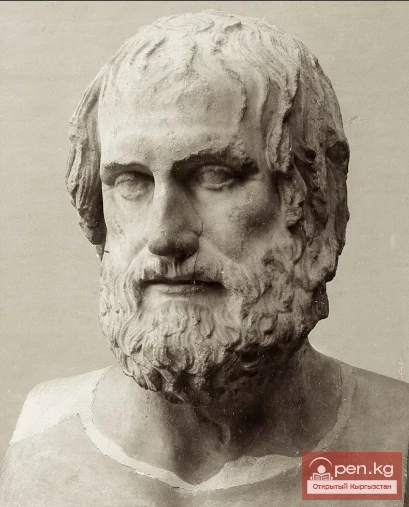

The author of the poem "Persica," the ancient Greek poet from the island of Samos, Cherilus, wrote:

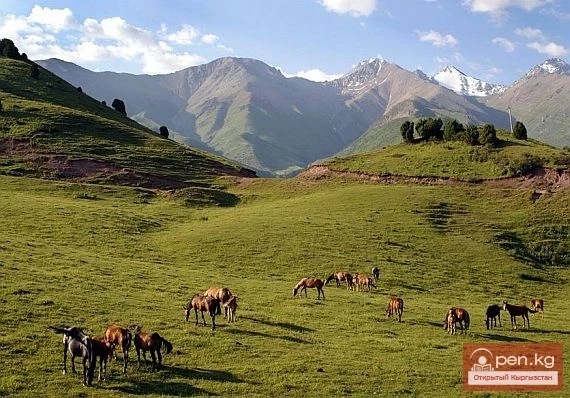

Saka, shepherds of sheep, of Scythian lineage,

Living in Asia, with abundant wheat.

Although the poem, written in the 5th century BC, has survived to us in fragments, there are few poetic lines that so succinctly and concisely address two main controversial questions of the real history of the Saka, which have long been the subject of discussions among modern historians. The first postulate of Cherilus — "Saka... of Scythian lineage" — was convincingly proven in the 19th century by the prominent Russian orientalist V. V. Grigoriev in a work titled with a slightly rephrased line from Cherilus. The scholarly world accepted the identity "Saka=Scythians," although there were still stubborn individuals who rejected it. The situation is more complicated with the second postulate — "shepherds of sheep... in Asia, with abundant wheat." How should we interpret Cherilus? Did he mean that the Saka herded sheep in Asia, where other peoples cultivated abundant grains, or did the Saka-shepherds also grow wheat themselves? This question is very important for historians, as it concerns the type of economy of the Saka: pure pastoralists or both pastoralists and farmers?

This question is also relevant regarding the economy of the Usuns.

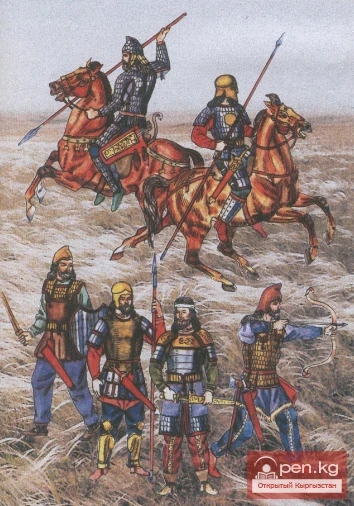

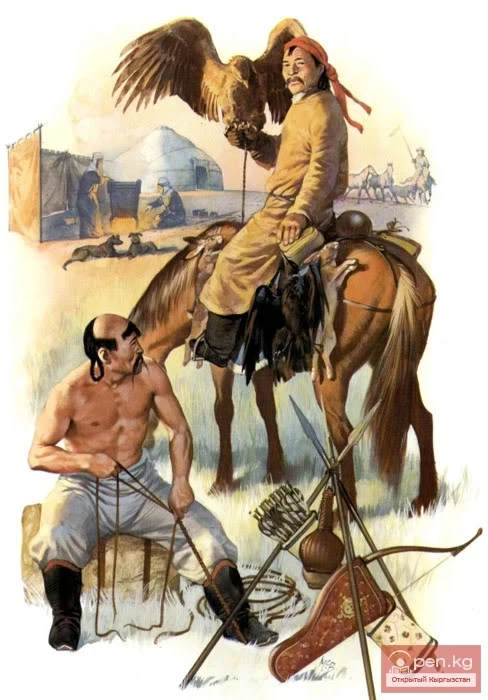

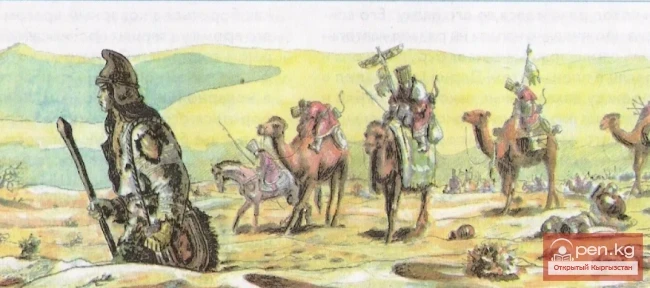

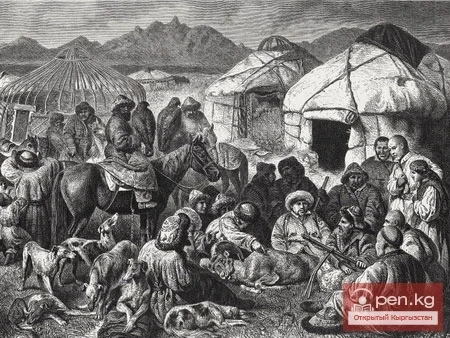

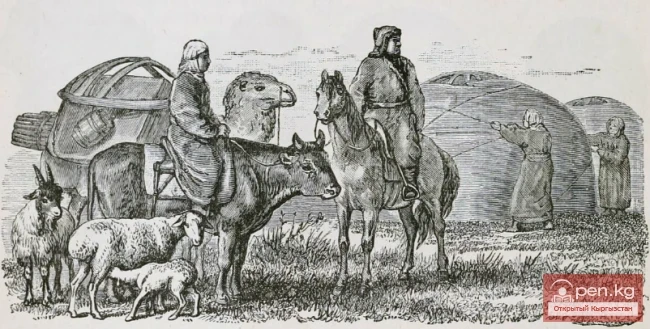

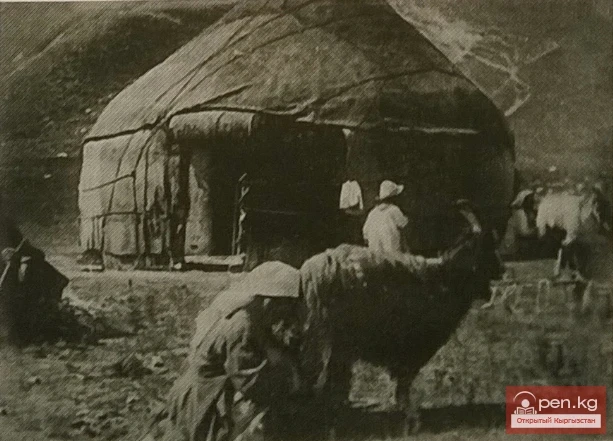

Ancient Greek authors vividly depicted the unfamiliar nomadic lifestyle of the Saka (Scythians). There were heavy covered wagons, which served as mobile homes, vast flocks of sheep, herds of horses, and cattle, along with the owners of this livestock — armed riders with taut bows, so "merged" with their horses that they had almost forgotten how to walk on their crooked legs, and the specific smell of nomads, and kumis, and many other exotic details that excited the imagination of the sedentary inhabitants of Greek city-states — farmers and craftsmen.

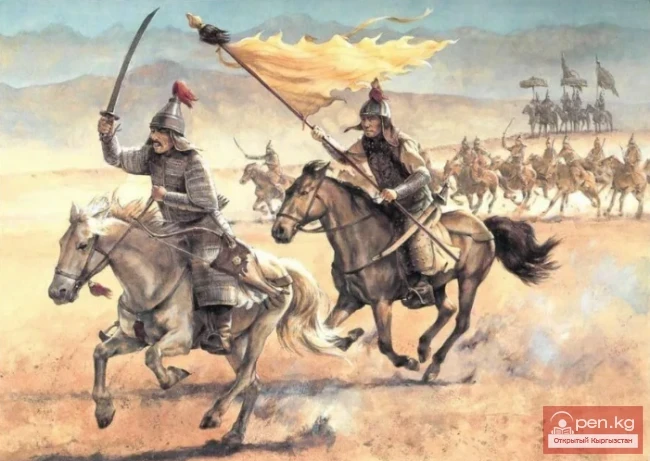

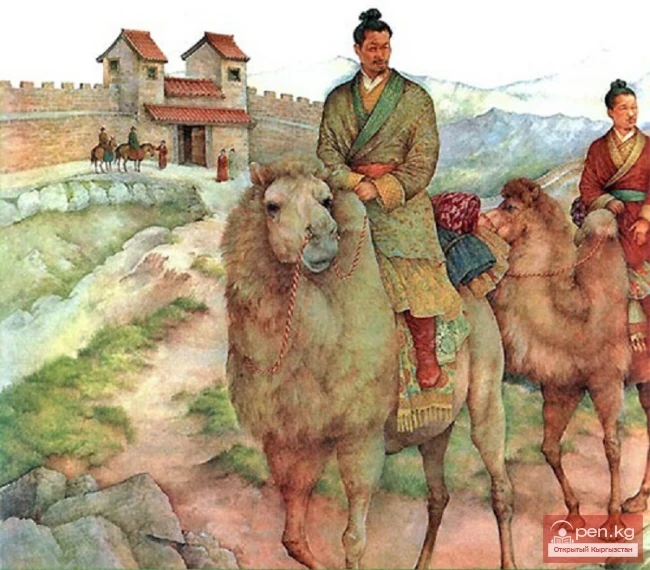

The same was written, independently of the Greeks, by ancient Chinese chroniclers about the Usuns and Huns for the rice growers and silk weavers of the Yellow River valley, frightened by the frequent raids of nomads.

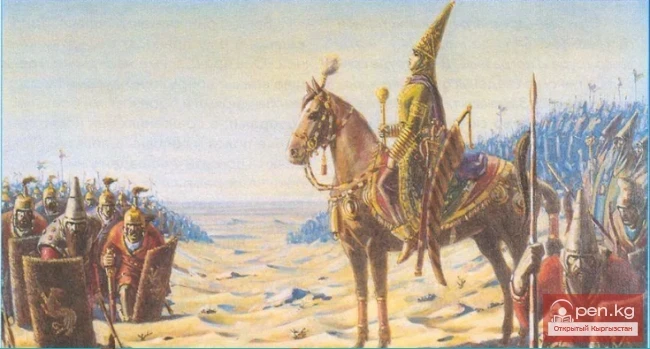

In agricultural civilizations, a stereotype of the nomadic herder was formed — the eternal shepherd-vagabond, wandering across the boundless expanses of steppes and mountains and knowing no homeland. He was conceived in one place, born in another, and raised far from both. The stunning emergence of the Cimmerian nomads and Central Asian Scythians into the Near and Minor Asia gave rise to the legendary image of the centaur — a horse with the torso of a man, which, as the embodiment of the nomadic herder, entered the mythology of many peoples.

The moral character of the nomads, judging by ancient writings, certainly left much to be desired.

For the steppe dwellers, it was nothing to organize mounted bandit groups for raids on agricultural oases, to burn settlements, to kill men, and to take women captive. From the skulls of slain enemies, they made cups from which they drank at feasts, wiping their beards with the scalps taken from those same heads. The nomads drank wine without diluting it with water, getting drunk to excess. And if they did dilute it, it was only with their own blood when concluding important friendly alliances. The nomads killed elderly men and then feasted on their flesh.

Such "tales" abound in the works of ancient authors from both the Mediterranean coast and the banks of the Yellow River. However, there is also a difference between them.

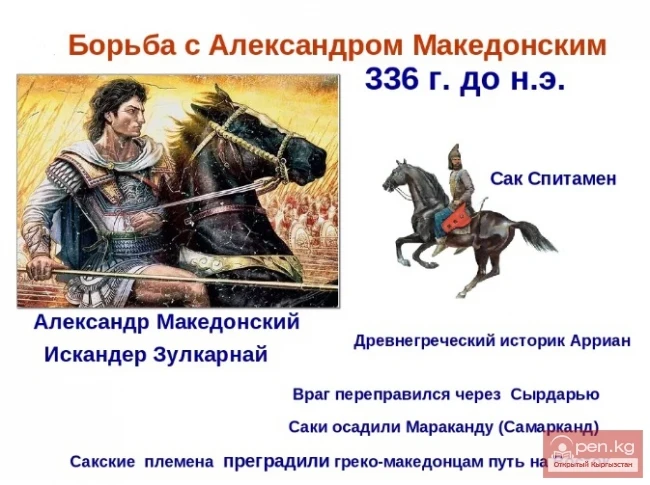

Ancient Greek authors, describing the Saka and Scythians, portray them as strange, incomprehensible, stern, yet just, wise, and active people. Their works include narratives about the wisdom of the Scythian Anacharsis, who was declared one of the seven sages of the world, the inventor of the flint, the anchor, the potter's wheel, and descriptions of the irresistible charm of the Saka queen Zarina, as well as the patriotism of the shepherd Shirak, who gave his life for the freedom of his native land.

We find nothing similar in the works of ancient Chinese authors, where nomads are depicted as predators who do not recognize human laws, lacking shame and conscience, whose thoughts are directed only towards murder for the sake of plunder. "Like wild beasts and birds" are how nomads are characterized in the "Han Shu" chronicle.

Thus, the rather harsh yet appealing image of the nomad created in the pages of Greek authors becomes repulsive and beast-like if one relies solely on ancient Chinese chronicles. This is just one example of the bias in ancient writings, which, indeed, manifests itself most vividly and immediately catches the eye. We cannot truly assume that the nomads were one way towards the Greeks and completely different in their contacts with the Chinese. The truth is simple: the Greeks and their colonies in the Black Sea region were in constant and predominantly friendly trade and cultural relations with their Scythian neighbors. Greek authors were greatly sympathetic to the successful struggle of the Scythians and Saka against the eternal enemy of Ancient Greece — Iran. There were no idyllic relations between the Greeks and Scythians; nevertheless, they rarely escalated into open hostility. In Central Asia, everything was the opposite. Ancient China and the nomads engaged in a long struggle, with varying success — a struggle for survival, in which deception, treachery, blows from around the corner and from behind, false oaths, and assurances were not considered disgraceful. Ancient Chinese empires, conducting a traditional great power policy towards "barbarians," cultivated hatred and contempt for them, emphasizing the inherent savagery and eternal backwardness of the steppe dwellers. Without such official propaganda, it is unlikely that the mobilization of vast human resources for campaigns deep into the steppes and especially for the construction of the Great Wall of China, as well as strategic military roads to it, would have been possible.

What Do the Kurgans of Preissykul Say??