It is known that the Bronze Age in Fergana was universally replaced by the time of the dominance of early nomads — the Saka-Haomavarka.

A vivid testament to the presence of the latter in the vicinity of Osh is the burial ground of Tuleyken, which was partially studied by A.N. Bernshtein. This is one of the connecting links between the Chust culture and the Davan kingdom — one of the ancient slaveholding states in the Fergana Valley. In the suburban areas of modern Osh (in particular, on the lands of the Kalinin collective farm in the Kara-Suu district), other monuments of antiquity have also been discovered.Somewhere not far from the city, in the 3rd century BC, the reconnaissance units of Alexander the Great passed through. Here, after receiving resistance, they were forced to turn sharply southeast, leaving only legends about themselves. The Suleiman Mountain of Osh inspired one of these legends about Alexander the Great and the famous Czechoslovak journalist Julius Fučík, who visited here in the 1930s. In his travel essays about Suleiman Mountain, there are lines: “At its peak, a large stone shines in the sun, smooth as a mirror. Look into this mirror and you will see the past, still quite recent, but more terrifying than the tale of the dragon that crawled from the peak of the opposite Tash-Ata and swallowed the entire army of Alexander the Great…”

But a legend is a legend. Authentic archaeological materials already irrefutably confirm that at this time, the population of the independent state of Davan lived here, famous for its "heavenly horses," whose images on the Aravan rocks have conveyed their "heavenly" lightness to our days.

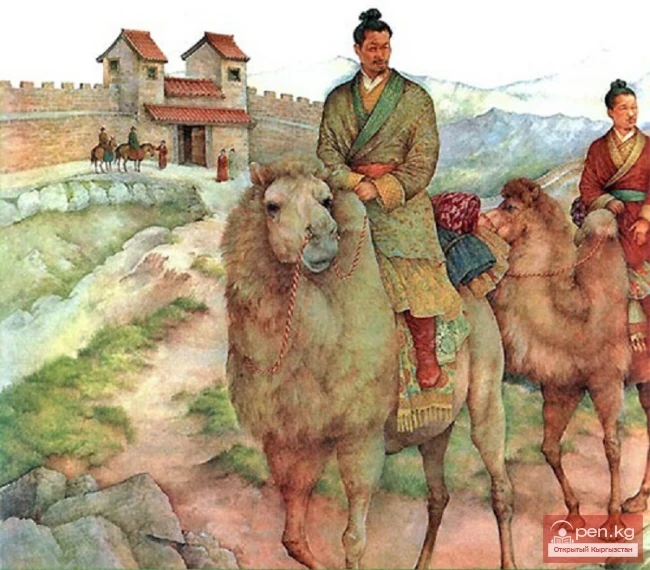

In the 3rd–1st centuries BC, the lands of modern Osh region and neighboring areas were inhabited by both pastoral nomads — the Saka, Usuni, and others, as well as ancient land cultivators, conditionally referred to as Davanites. The latter, as known from Eastern written sources, engaged in both animal husbandry and agriculture. Far beyond the valley, Davan's argamaks were famous. The population cultivated barley and rice, sowed alfalfa (for feeding livestock), and grew grapes and fruit trees. The Davanites traded with countries of the West and East, being connected to them by the Great Silk Road.

Archaeological finds discovered in the territory of the city, as well as during excavations of the surrounding hills — tepe and at the Akburin settlement, indicate significant development of agricultural culture during the period of the Davan kingdom. It can be assumed that the emergence of Osh as a city dates back to this time. However, only in the early Middle Ages, after the Arab invasion, did Osh develop into a major urban center.

In the 1st–4th centuries AD, the cities and villages of Fergana were part of the slaveholding state of Kushan. To this day, heavily leveled burial mounds from the Kushan period remain in the vicinity of Osh, where burials with various accompanying inventory have been discovered, including vessels made on a potter's wheel, jewelry, and weapons.

Recent finds from the same period near the city at multi-layered sites (the Koshtepe settlement near the village of Madaniyat and others) are also of interest in this regard.

Subsequently, in the 5th–8th centuries, some of the settlements, still known as Davan (about 70 large and small settlements of that time were mentioned in Eastern chronicles in the Fergana Valley), functioned as castles and fortresses of the early feudal society period in Fergana. It is likely that Osh also developed during this time, with its special significance determined by the important cult-ideological function caused by the traditional worship of the famous mountain.

Summarizing the archaeological excavations and determining the stages of the formation of the city of Osh, Yu.A. Zadneprovsky writes that the first stable sedentary-agricultural settlement that arose here three millennia ago is the progenitor of the modern city, its ancient core. The second stage is associated with the early Iron Age and is represented by materials from the so-called Eilat period (6th–4th centuries BC). The third stage refers to the Davan kingdom in Fergana at the turn of our era.

Archaeological work continues. The outlined contours of the ancient history of the city are being filled with new concrete material every year. The establishment of the Osh Regional Museum-Reserve serves as a new stimulus for expanding excavations, deepening research, and our understanding of the origins of the city of Osh itself.