Central Asia and Tian Shan in the 6th—5th centuries BC

In the first millennium BC, a new ethnic community—the Saka—emerged from a conglomerate of Bronze Age tribes. The transition from primitive society to class society was accompanied here by the development of a new mode of economy—nomadic animal husbandry and the formation of large tribal unions. In the 8th—1st centuries BC, nomadic tribes inhabited the vast expanses of Eurasia from Tuva to Ukraine (including its territory), referred to in ancient Persian cuneiform texts as Saka and by Europeans as Scythians. It is presumed that the word “Saka” meant “strong man (warrior).”

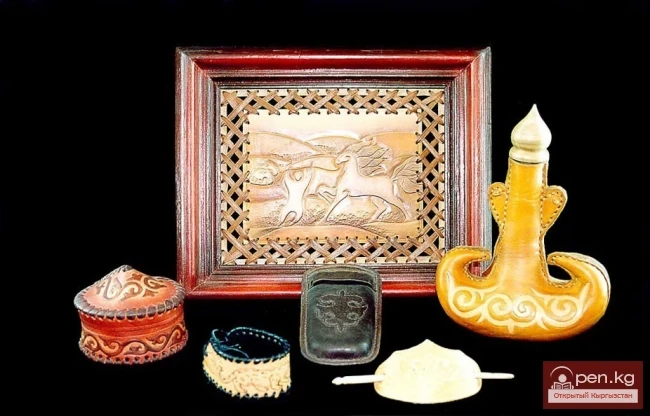

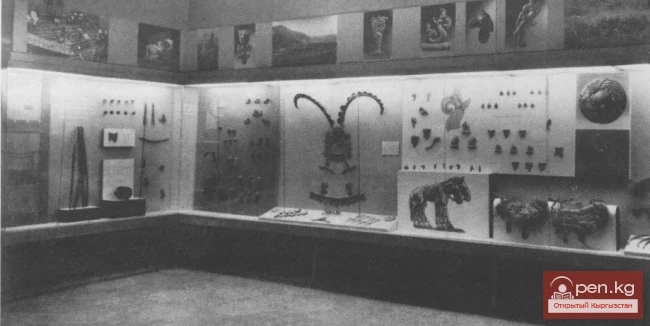

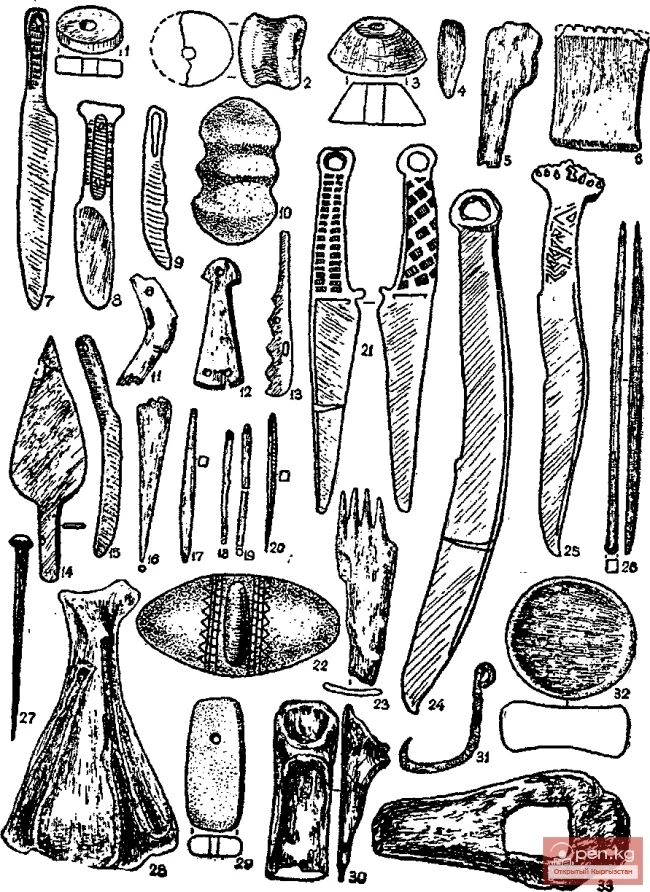

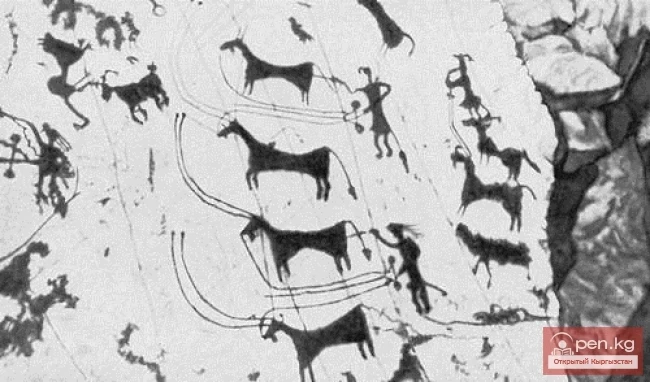

Many archaeological finds testify to the unity of these nomadic tribes. During excavations of burial mounds on the western and eastern fringes of their territories, archaeologists discovered similar weapons and household items, horse gear, and other domestic artifacts decorated in the so-called “Scytho-Siberian animal style.” In other words, across a vast area, including Semirechye and Tian Shan, a unified process of forming the culture of ancient nomads was underway.

In the 6th—5th centuries BC, the Central Asian tribes of the Saka formed into two major tribal unions, so it is only possible to speak of the borders of their territories approximately. One of them occupied the territory from the Caspian Sea and Uz-boy to Central Tian Shan and the Ili River.

According to ancient written sources, in the 6th—5th centuries BC, two major confederations of tribes inhabited the territory of Central Asia and Tian Shan: the Saka—Tigrahauda (according to Persian sources), also known as the Saka—Ortocoribantia (according to ancient Greek sources), and the Saka—Haumavarga (according to Persian sources), also known as the Saka—Amurgi (according to ancient Greek sources).

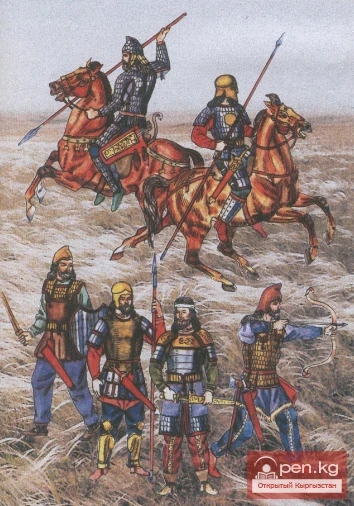

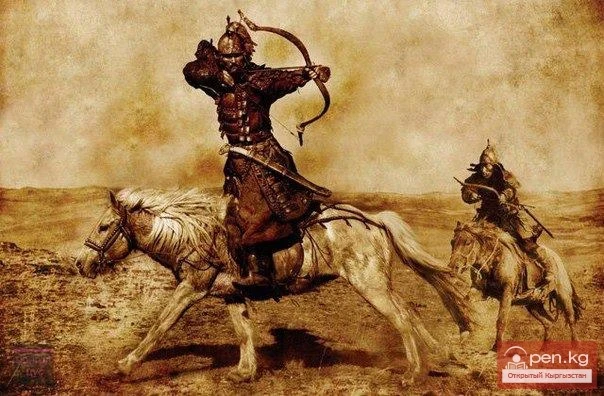

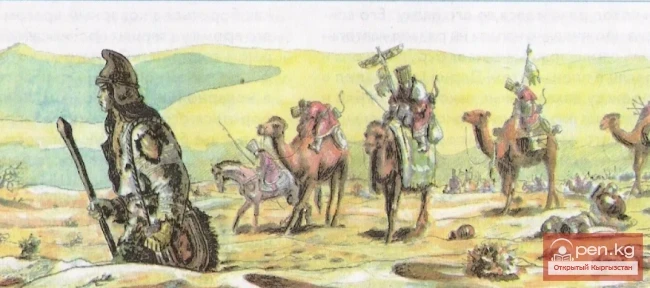

The Saka union consisted of the tribes of Yaksarts, Massagets, Issedones, and Daidaks. The Saka were a warlike tribe that played an active role in the political events of Central Asia in the first millennium BC. Every adult Saka was considered a warrior and was obliged to take part in a campaign at the call of the leader, fully armed and on his horse. The Saka cavalry was considered the best in the world.

The Economy of the Saka.

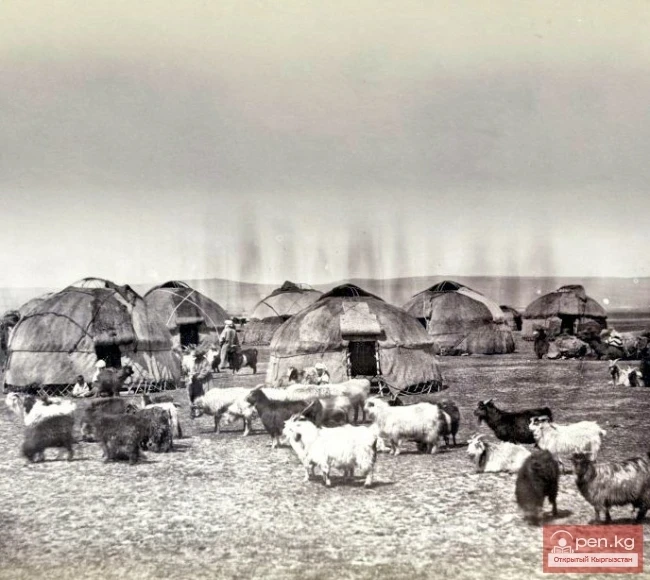

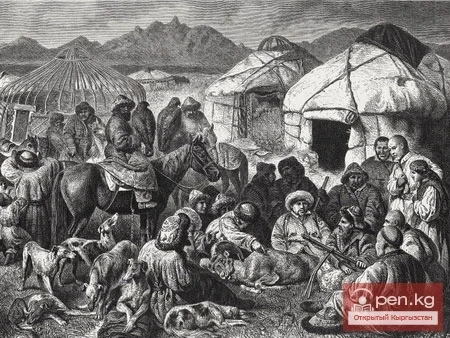

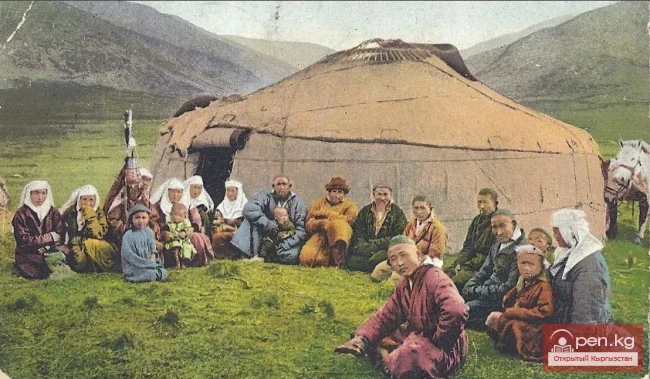

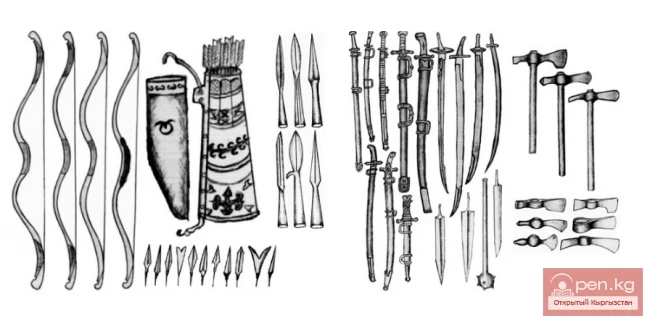

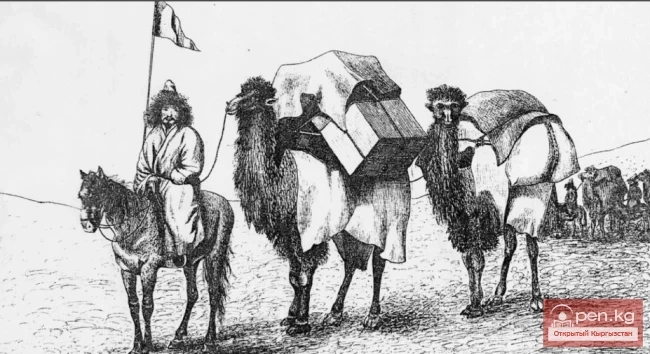

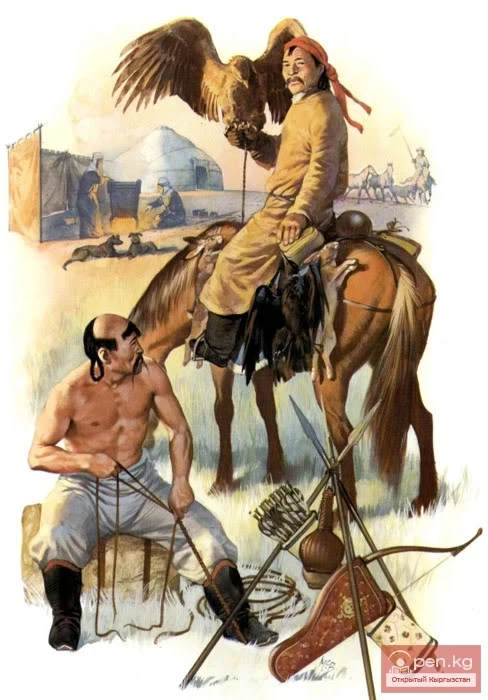

The Saka spoke a language of Eastern Iranians. Based on the remains of ancient people found by archaeologists in Alai, Central Tian Shan, in the Ketmen-Tyube area, it was established that they externally belonged to the Europoid race. Only a small part of the Saka had Mongoloid features. They engaged in nomadic animal husbandry year-round. Depending on the season, they migrated with numerous flocks of sheep and herds of horses across pastures. For that era, nomadic economy was a progressive form, as it provided valuable products such as meat, milk, butter, cottage cheese, and kumis. From wool and hides, nomads made warm, durable clothing, kiyiz felt coverings and carpets for their dwellings, and they wove ropes from horsehair. They mastered unsuitable for agriculture territories such as steppe plains, deserts, and semi-deserts, as well as foothill gorges and ravines. Most importantly, ancient nomads knew how to manufacture necessary tools, weapons, axes, knives, spearheads, as well as household items like dishes, mirrors, needles, and jewelry from metal. Bronze still had significant use in the economy of the nomads. By the beginning of the first millennium BC, people learned to smelt iron. Thus, the Iron Age succeeded the Bronze Age, which continues to this day.

Social Structure of the Saka.

A few written sources have preserved scant information about the social structure of the Saka who lived in the 6th—5th centuries BC. They mention the words “king,” “lord,” and “warrior.” In general, their social structure can be characterized as follows: small patriarchal clans united into nomadic communities, several such nomadic communities formed a tribe, and tribes united into tribal unions. By the 5th century, property and social inequality began to manifest in the social structure of the Saka, evolving into class distinctions. This is also confirmed by archaeological excavations. Under large burial mounds of kings, archaeologists find real treasures, for example, up to 4,000 items made of gold and silver, while in the graves of ordinary community members, there are one or two clay bowls.

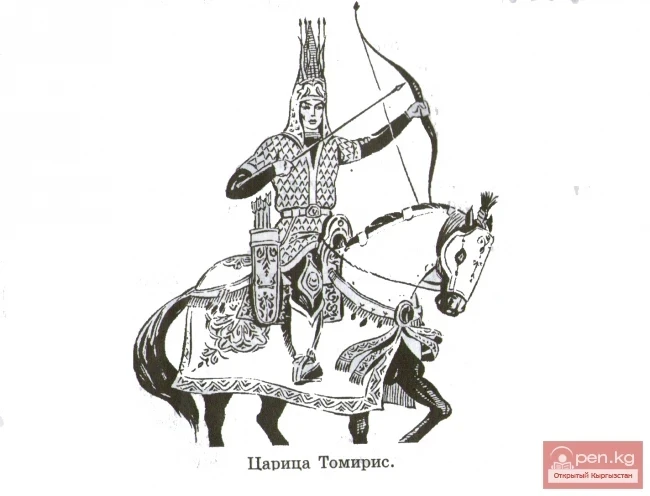

At the very bottom of the social pyramid were slaves, captured by the Saka during battles and wars. However, they did not play a significant role in the economy due to their small numbers. Every Saka who reached adulthood was considered a warrior. At the call of the leader, he donned military armor, took weapons such as a bow, sabre, axe, mounted his horse, and set out for a campaign. From early childhood, Saka boys were trained to sit in the saddle, handle a horse, and shoot a bow, which is why Saka cavalrymen were considered the best in the world. The warriors were so skilled with the bow that while galloping, they could turn around and accurately hit their target. The kings of Assyria invited the Saka as mentors for their warriors to teach them archery. In the 5th—4th centuries BC, heavily armed cavalry units dressed in iron armor, helmets, and chain mail appeared in the Saka cavalry. They formed the elite guard of the kings.

The Army.

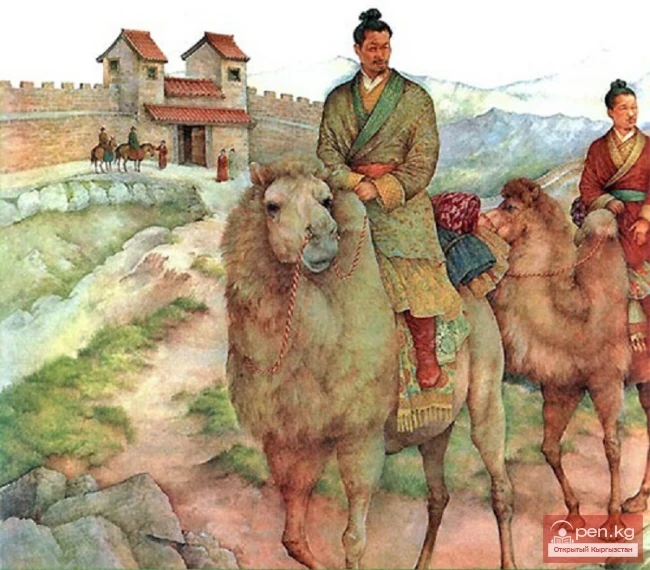

The nomads of Central Asia maintained peaceful and military relations with the Persians, the people of Iran, and participated in the economic, cultural, and political life of the ancient world. A twelve-thousand-strong detachment of Saka helped the Persian king Cyrus II achieve victory in the war against the powerful Assyria. The Saka participated in athletic competitions held in the palace of the Persian ruler. For example, one Saka youth won all the equestrian competitions organized by Cyrus II.

As the great Herodotus recounts in his “Histories,” the Saka participated in all significant events of that period as early as the 5th century BC, such as the Greco-Persian Wars (500—449 BC). As allies, sometimes as mercenaries, the Saka fought on the side of the Achaemenids. The Saka cavalry defeated the Athenian hoplites (heavily armed infantry) at the Marathon battle (490 BC). The Saka infantry participated in the battles at Thermopylae (480 BC) and Plataea (479 BC). It is also known that the steppe Saka were part of the crews of Persian warships. To conquer Greece, the Persian commander Mardonius included the Saka in his elite troops. According to written sources, camps for Saka troops were established in the cities of Egypt and Babylon, and the Persian garrison stationed in the Egyptian city of Memphis was entirely formed from Central Asian Saka. The name of one of them, Sakiat, has been preserved in written sources and has reached us. In various locations of the former Persian empire, which stretched from Central Asia to Egypt, clay figurines wearing pointed hats, dressed in coats, and shod in boots, resembling Saka warriors, as well as Tian Shan Saka-Tigrahauda, have been found.

Military Successes of the Saka.

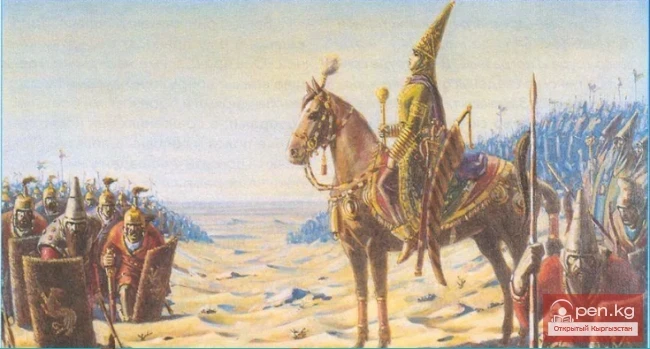

The Saka had an unparalleled international reputation: they were considered invincible warriors. In the 6th century BC, the Tigrahauda Saka were forced to engage in a fierce struggle for their independence against a very strong enemy, the Persian king Cyrus I. In 550 BC, this ruler decided to subjugate the increasingly powerful Saka tribes of the Massagetae in the northeast of the Persian state, led by Queen Tomyris, and then conquer Egypt.

To fight against Cyrus II's hundred-thousand-strong army, Queen Tomyris had to oppose it with an equally powerful force. Not only the Saka tribes, whose lands Cyrus II intended to subjugate, but also tribes from neighboring territories, as well as other Saka-Tigrahauda tribes, including those from Semirechye and Issyk-Kul, joined the fight against the Persians.

In the summer of 530 BC, halting his troops before the river that separated him from the Saka, Cyrus II sent envoys to Queen Tomyris, who was a widow, with a proposal to become his wife. Understanding that the Persian king sought not a wife but the vast possessions of the Saka, their wealth, and brave warriors, the queen declined. Cyrus II, who was only waiting for a pretext to start a war, crossed the river at the head of his troops. The Saka observed him but did not attempt to interfere. Tomyris believed that the enemies would find it difficult to fight on foreign soil, and when they turned back, the wide expanse of the river would become an insurmountable barrier for them. Advancing deep into Saka territory, Cyrus II halted his troops. He decided to cunningly lure the Saka into a trap: he pretended to be frightened and turned back, leaving behind, as if in haste, a large supply of wine. The plan was simple, but the outcome was successful. As Cyrus II had anticipated,

Tomyris sent a third of her army in pursuit, led by her only son Sparganist. The Saka occupied the deserted Persian camp, found the wine, and, taking advantage of their commander's inexperience, held a feast. Under the cover of night, Cyrus II returned and destroyed the carelessly sleeping Saka. According to some sources, Sparganist was killed by the Persians, while others say he was captured but took his own life, unable to bear the shame. Tomyris sent an envoy to Cyrus II demanding that he immediately leave Saka land and return her son's body. The letter ended with a threat: “If you do not do this, I will make you drink blood, I swear by the sun that the Massagetae worship”. Cyrus II ignored the threat. A fierce battle began, in which the Saka managed to lure the Persians into a narrow gorge and slaughter them. According to legend recorded by the Greek historian Herodotus, Tomyris ordered that the head of King Cyrus II be placed in a wineskin filled with blood and proclaimed: “You wanted blood. You got it!”

However, later the Saka were subdued by his successor Darius Hystaspes in 519—518 BC. The united forces of the Saka tribes of Central Asia, including those occupying the territory of ancient Kyrgyzstan, participated in the hard struggle against the Achaemenid state. In response to the mobilization of all Achaemenid forces from the Mediterranean to the Hindu Kush (Cyrus II had a two-hundred-thousand-strong army), the Saka kings had to concentrate the nomadic forces from Tian Shan to the Caspian Sea. Only in this way could the Saka meet the foreign invaders with dignity.

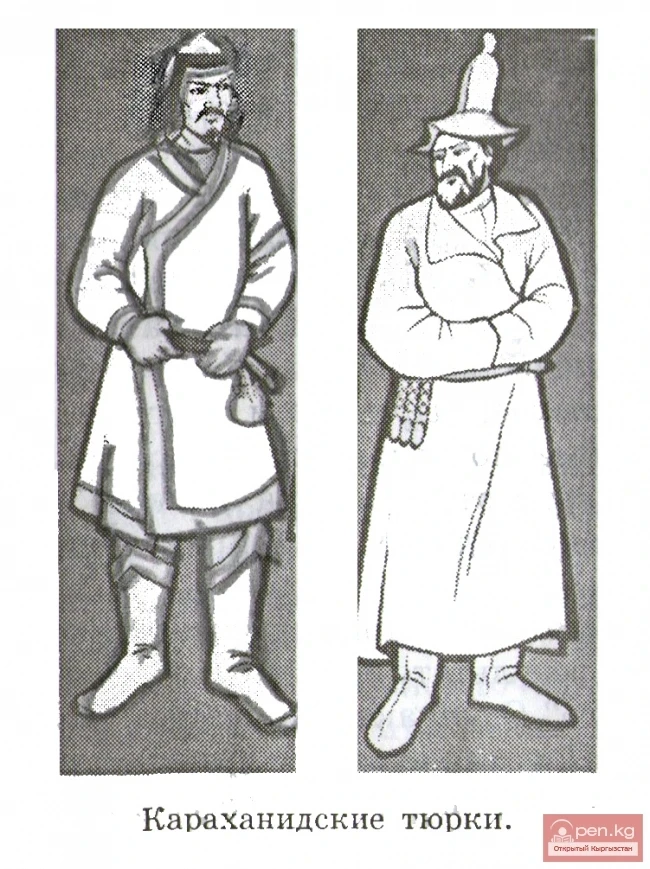

Significant influence in agriculture came from contacts with the sedentary population, especially the Sogdian people, distant ancestors of the Tajiks, who began to settle in the Chuy and Talas valleys. Over time, they mixed with the Turkic-speaking population, adopting its customs and traditions.

The Saka, inhabiting Fergana, the Tashkent oasis, and Tian Shan, had to defend their independence in the struggle against one of the greatest conquerors in world history—Alexander the Great. The conqueror defeated the armies of Achaemenid Iran in a series of battles and was already on the banks of the Syr Darya in 329 BC. Here, near modern Khujand, he built a city. The king of the Saka, who lived north of the river, realized that this city was “a yoke on his neck.” (There is an opinion that this king's residence was in Ketmen-Tyube, on the territory of present-day Kyrgyzstan). The nomadic ruler sent envoys to Alexander. The speech addressed to the conqueror, as transmitted by the ancient historian Quintus Curtius Rufus, testifies to the dignity, skill, and excellent orientation of the ancient Tian Shan diplomats in world politics: “If the gods wished to make the size of your body equal to your greed, you would not fit on all the earth. You boast that you have come to pursue robbers here, while you yourself are robbing all the tribes you reach. You have occupied Lydia, captured Syria, hold Persia, Bactria is under your power, and you have coveted India: now you stretch your greedy and hateful hands to our herds. Cross only the Tanais (Syr Darya—Ed.) and you will learn the breadth of our expanses. We pursue and flee with equal swiftness; consider whom you would like to have in us, enemies or friends”. Alexander did not heed the words of the nomadic sages and crossed the Syr Darya. In a bloody battle, the Greeks won, but then returned across the river and never crossed the border again.

The Saka managed to preserve their independence. The influence of Greek culture only slightly touched the tribes of the Tian Shan Saka. In numerous burial mounds of that time, excavated by archaeologists in Ketmen-Tyube, in the Issyk-Kul region, and in Alai, alongside the traditional set of Saka weapons and household items made in the so-called “Scytho-Siberian animal style,” decorations clearly bearing the spirit of Hellenism are found.

In the territory of present-day Kyrgyzstan, turbulent political and military events occurred:

a) for five centuries, starting from the 7th century BC, the pastures were owned by Iranian-speaking Saka (Eastern Scythians), distant ancestors of the nomadic peoples of Central Asia.

b) The successors of the Saka were the Iranian-speaking Usuni—from various ethnic groups of Central Asia.

c) From the 3rd century BC, they were succeeded by the Huns.

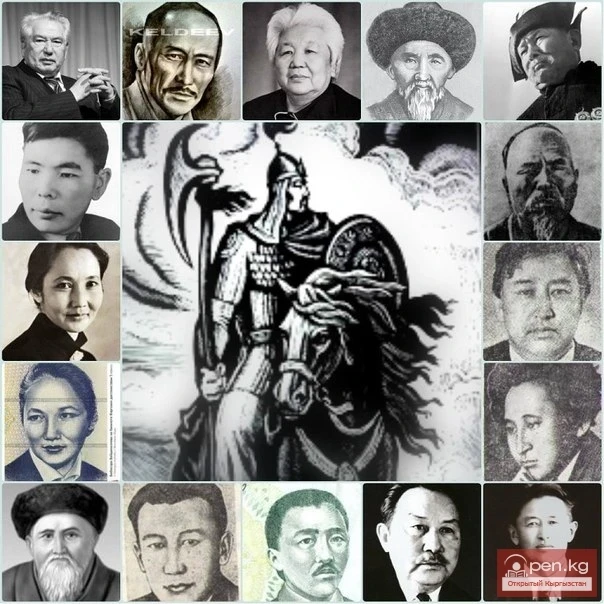

Kyrgyz in Antiquity