The Disgraced Monk with Seditious Prayer Beads

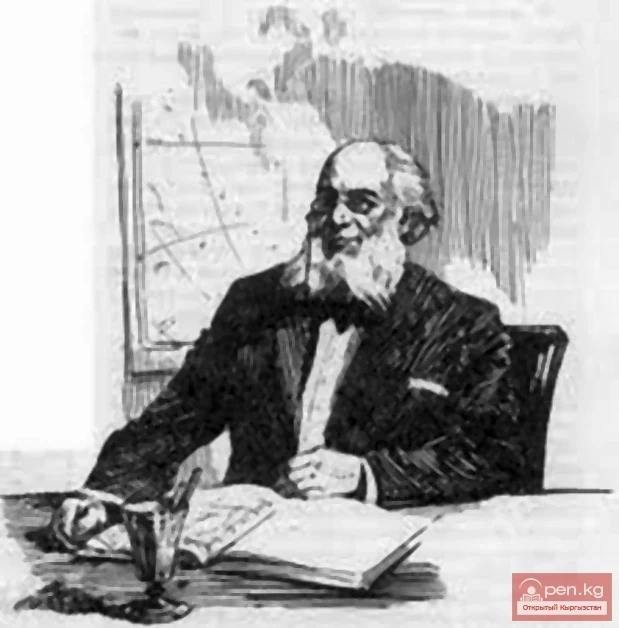

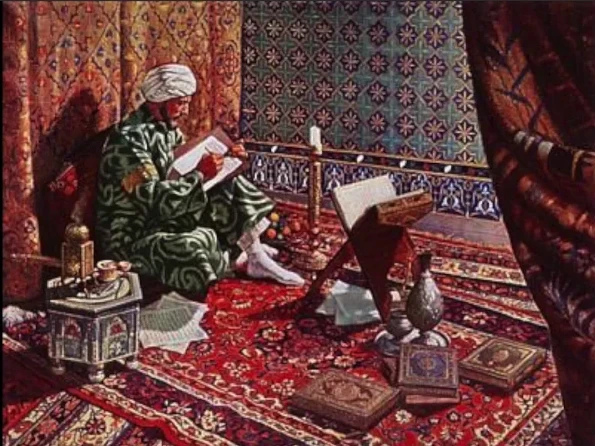

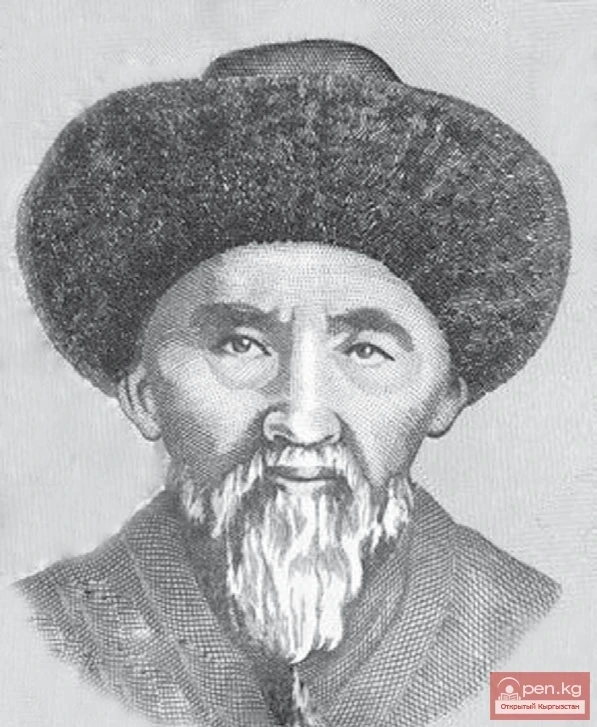

In early May 1853, in the cold cell of the St. Alexander Nevsky Lavra in St. Petersburg, a lonely and forgotten prominent Russian sinologist, a scholar of international renown — the monk Iakinf — was dying. He had long ceased to eat and respond to the questions of the novice who was voluntarily caring for him. The day before his death, one of his colleagues from the Asian Department visited him. The old man's faded brown eyes were motionless. It seemed he neither saw nor heard his visitor. Finally, the visitor asked a question in Chinese. The dying man instantly transformed; his eyes sparkled, and a flush appeared on his sharply protruding cheekbones. He smiled and began to speak. He spoke for a long time and continuously, as if savoring the language, to which he had devoted all his strength in understanding its finest nuances. By morning, he was gone. On the modest obelisk above the monk's grave, buried within the confines of the lavra, one can still read the hieroglyphs that say: "He constantly and diligently worked on the historical works that immortalized his glory."

Let us briefly turn to the milestones of his extraordinary life and truly scientific feat.

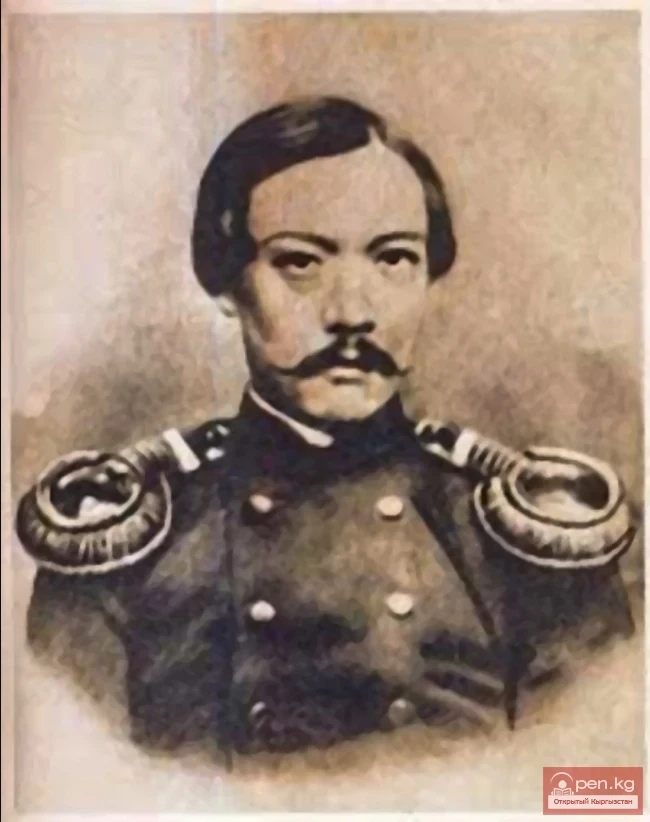

The outstanding Russian orientalist Nikita Yakovlevich Bichurin, known to the world by his monastic name Iakinf, was born on August 29, 1777, in a remote Chuvash village to the family of a deacon of the local church. Having brilliantly graduated from Kazan Seminary, he took monastic vows in 1802 and became the archimandrite of the Irkutsk Ascension Monastery. However, for violating the statutes, the young archimandrite was stripped of his position and exiled to the Tobolsk Monastery. The Holy Synod was in dire need of talented church figures. Therefore, in 1807, Father Iakinf was appointed head of the Russian spiritual mission in China and archimandrite of the Sretensky Monastery in Beijing.

This appointment marked an important stage in N. Ya. Bichurin's life. It was here that his abilities as a historian and linguist were revealed. Throughout his 14 years in China, he studied the Chinese spoken and written language with extraordinary energy and persistence, researched and translated Chinese historical chronicles into Russian, and wrote historical works. The archimandrite was burdened by the affairs of the spiritual mission and the monastery's economy. Practically, he did not engage in them, granting complete freedom of action to his assistants. As expected, the mission's economy fell into such decline and neglect that upon his return to Russia in 1821, Iakinf was stripped of his rank and exiled to the Valaam Monastery.

This fact did not discourage the exile. It seemed that he himself sought detachment from all burdensome responsibilities associated with high church positions. In the secluded cell of the monastery, he continued his uninterrupted vigils over the Chinese books brought from Beijing, the number of which was so great that a caravan of 15 strong camels delivered them to Russia.

Four years later, he was released from his Valaam cell at the request of a prominent figure in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, P. L. Shilling, and traveler E. F. Timkovsky, who highly valued Iakinf's unique sinological knowledge and hoped to find practical applications for it. The Tsar ordered N. Ya. Bichurin to be assigned to the Asian Department. However, the new official was not seen at work; he secluded himself in the cell of the Alexander Nevsky Lavra and continued his ascetic labor. In three years (1828-1830), N. Ya. Bichurin published six books and numerous articles in well-known journals. The astonished world eagerly acquainted itself with the country revealed by the disgraced monk as if from the inside. For the first time in European literature about China, it was not portrayed as a backward exotic country with a poor and destitute people. Iakinf managed to view China not with the contemptuous gaze of a European but through the eyes of a Chinese person, truthfully and respectfully reflecting what he saw in his works. In 1848, the scholar sharply opposed the plundering of China by European powers as a result of the "Opium War," for which he was criticized by reactionaries of all kinds and nations, who regarded the act of defending China as an "attack on European culture." However, even N. Ya. Bichurin's opponents could not help but note his unique work ethic and encyclopedic knowledge in the field of sinology. The well-known German scholar J. Klaproth, who constantly debated with N. Ya. Bichurin, wrote: "Father Iakinf alone accomplished as much as an entire scholarly community could do."

N. Ya. Bichurin never took his monastic title seriously. He closely linked his fate with the progressive Russian public thought. His friendship with A. S. Pushkin is well known. In the poet's library, there are books by N. Ya. Bichurin with authorial inscriptions. A. S. Pushkin used them in his historical works, especially in "The History of Pugachev."

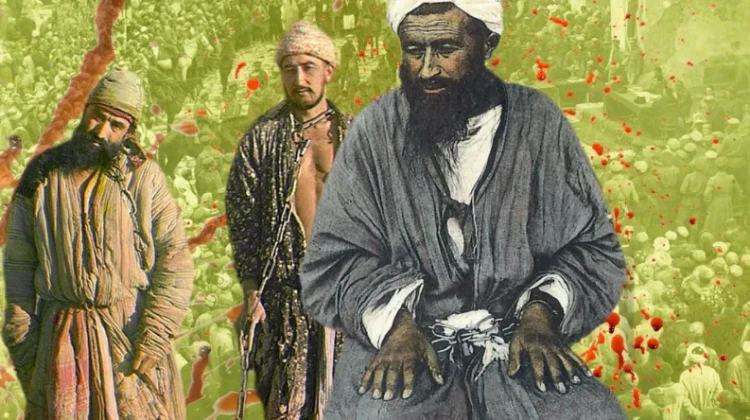

In 1830, N. Ya. Bichurin committed an act unprecedented in Nicholas-era Russia. Five years after the Decembrist uprising on Senate Square, when even the names of the exiles were dangerous to pronounce, he met in Transbaikalia with one of the leaders of the Decembrists, N. A. Bestuzhev. What the scholar and the revolutionary discussed remains unknown. However, the silent witnesses of this meeting speak eloquently of their mutual friendly disposition. In the Kyakhta Museum, there is a portrait of N. Ya. Bichurin painted by N. A. Bestuzhev. He also gifted the monk prayer beads made from his own shackles. With these seditious prayer beads, the disgraced monk appeared in the salons and drawing rooms of St. Petersburg. Such an open demonstration did not go unnoticed. The monk became dangerous. And when in 1831 N. Ya. Bichurin submitted a petition to be relieved of his spiritual rank, the Synod, wishing to rid itself of the restless monk, agreed. Nevertheless, Nicholas I imposed a resolution on the petition: "On the 20th day of this May (1832 — Ed.), His Majesty graciously ordered: to remain in residence as before in the Alexander Nevsky Lavra, not allowing the abandonment of monasticism."

Through his asceticism and scientific knowledge, N. Ya. Bichurin earned deep respect from European and Russian scholars. In 1828, he was elected a corresponding member of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences, and in 1831 — a member of the "Asian Society" in Paris. His books were translated into European languages. For his works, N. Ya. Bichurin was awarded the full Demidov Prize four times (in 1834, 1838, 1842, and 1851). He was a regular contributor to nearly twenty periodicals. By the end of his life, feeling a decline in strength, N. Ya. Bichurin withdrew from all public and current literary affairs, secluded himself in the Lavra cell, and began writing the main work of his life — the three-volume "Collection of Information about the Peoples Inhabiting Central Asia in Ancient Times" (1846-1848).

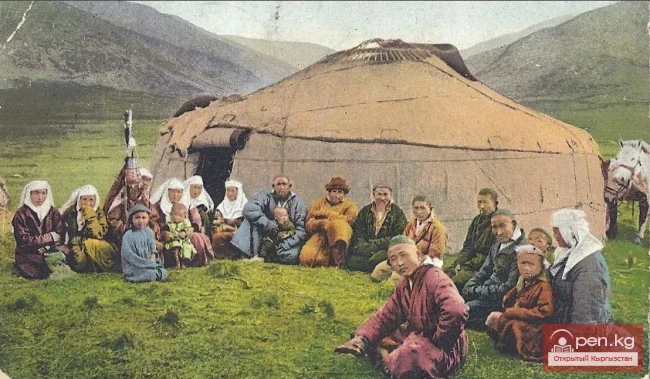

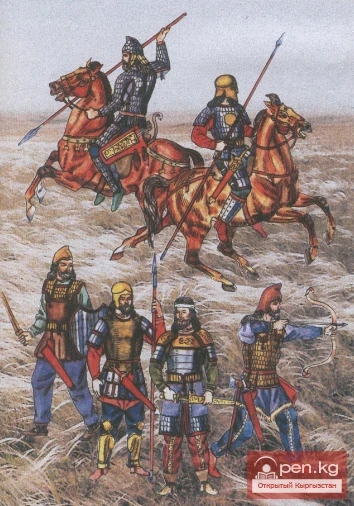

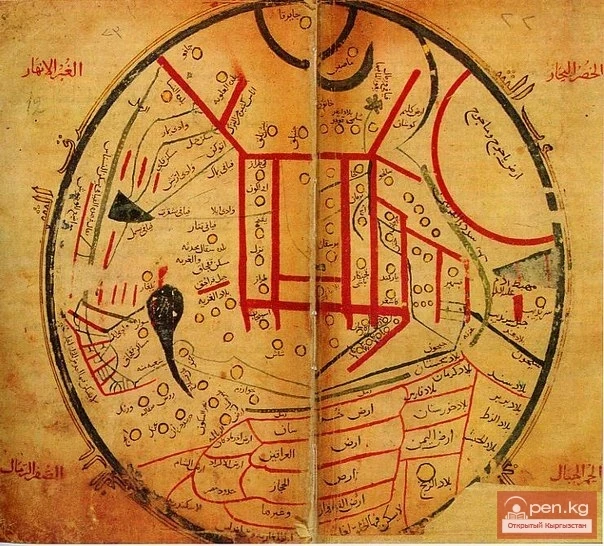

In the humanities, there are works that remain relevant for 10-20 years; rare are the writings that have not lost their scientific significance after 50 years, and truly unique are those that have survived for centuries. To the latter, with full justification, one can refer to the monumental three-volume work of N. Ya. Bichurin, "Collection of Information about the Peoples Inhabiting Central Asia in Ancient Times," which scholars have been referring to for almost 150 years. The "Collection of Information" contains a vast amount of material on the history of the peoples of Southern Siberia, the Far East, Central and Central Asia from the 2nd century BC to the mid-9th century, expertly compiled and translated from ancient Chinese chronicles, inaccessible not only to the average reader but also to scholars who are not sinologists. The translations are accompanied by meticulously executed commentaries and ancient Chinese maps.

The significance of this work by N. Ya. Bichurin (Iakinf) for the history of Central Asia cannot be overstated. Thanks to him, the names of the tribes that inhabited Kyrgyzstan in ancient and medieval times became known, along with the main points of their political history, information about their dynastic, ethnic, and trade connections. The sources, first introduced into scientific circulation by N. Ya. Bichurin, made possible the existing periodization of the history of ancient and medieval Kyrgyzstan and the correlation of the main archaeological material with it.

The ethnic attribution of archaeological materials obtained from the waves of Issyk-Kul at the settlement of Sarybulun has compelled us, like many researchers, to also turn to the invaluable information left for posterity in the works of our renowned sinologist.

Iranian-speaking nomads — the Sakas