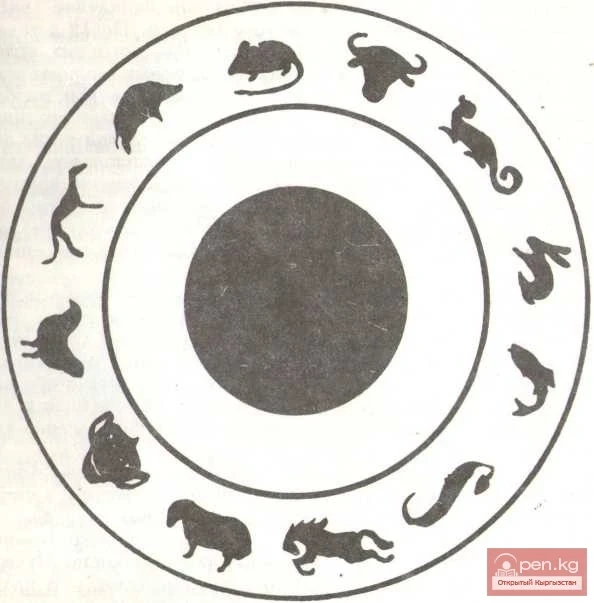

Kyrgyz Calendar with a 12-Year Cycle

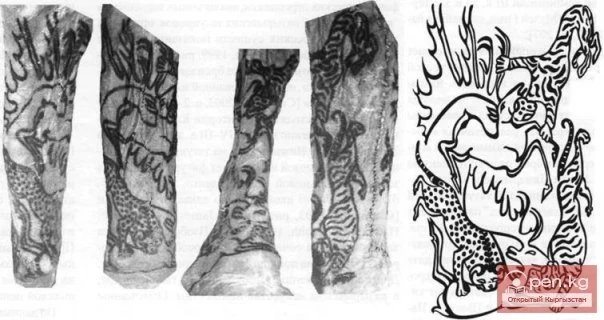

Among the Kyrgyz (as well as many other peoples), a 12-year cycle of counting years was practiced, where a specific year was named after an animal: chychkan — mouse, uy — cow, bars — snow leopard (sometimes jolbors — tiger), koyon — hare, zhayaan — catfish (sometimes dragon), zhylaan — snake, zhylyky — horse, koy — sheep, mechin — monkey, took — chicken, it — dog. The acceptance of the 12-year cyclicality contains, on one hand, a certain objective basis, and on the other, reflects the figurative thinking of the people, identifying the character of the year with the character of the animal whose name it bears. For example, the Kyrgyz believed that a person born in the year of the tiger should be strong, brave, flexible, and pursue their goals, but can also be vain, overconfident, and selfish. Men born in the year of the snake are quite passionate, while women are beautiful, romantic, and fickle; in the year of the sheep, they are calm and patient with cold and hunger. Women born in the year of the mouse tend to be short, have many children, and are energetic in their actions.

Those born in the year of the horse become popular, have a cheerful character, are intelligent, perceptive, talented, skilled in many things, and everything goes well for them, etc.

Interesting are the explanations of the ancestors of the Kyrgyz regarding why the mouse, rather than a larger animal like the camel, made it into the calendar of year names. Many different animals awaited the arrival of the year with impatience, but the cunning mouse stealthily climbed onto the hump of the camel and saw the approach of the year before the overconfident camel did (relying on its height, the camel ended up with nothing).

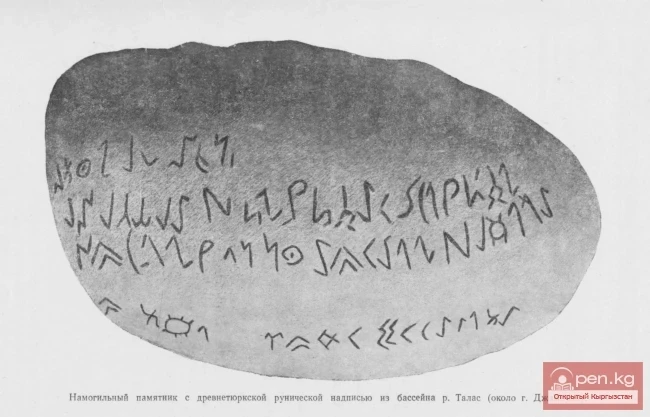

The world-renowned historian, academician V. V. Bartold noted that in the Chinese history of the Tang dynasty (618—907 AD), “... it is precisely the Kyrgyz who are mentioned as having a twelve-year cycle of years denoted by the names of animals.”

The Kyrgyz calendar was relatively accurate. “This cycle, as a unique invention of the Kyrgyz, perhaps the only phenomenon mentioned in history, deserves special attention.”

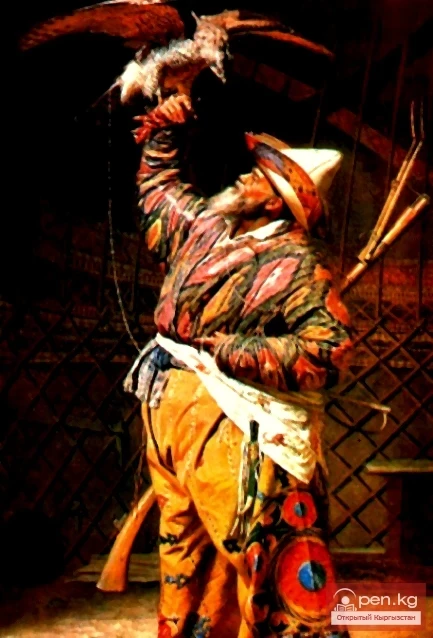

Let us turn to examples showing how the animal cycle was applied in practice, in life. Each 12-year cycle was called muchol by the Kyrgyz. It was used to determine a person's age. First, they would visually assess how many 12-year cycles a person had lived. Then they would find out in which year they were born. For example, if a person was born in the year of the mouse, the count would go as follows: from the year of the mouse to the year of the mouse inclusive is 13 years (bir muchol — one cycle), another mouse — 25 years (eki muchol — two cycles); suppose this year is the year of the monkey, before the monkey comes the cow (26 years), tiger (27 years), hare (28 years), dragon (29 years), snake (30 years), horse (31 years), sheep (32 years), monkey (33 years). Thus, this person is 33 years old. In each family, when a son turned 13, they would slaughter a ram, inviting relatives, friends, and the birthday boy's companions. The head of the family (father or mother, if the father was absent) would give a speech before the feast: “You have completed one cycle; always be ready to overcome life's difficulties.” After this ceremony, the father would fully trust the son to independently herd the livestock, hunt with trained birds, etc. A boy whom adults trusted to go to the formidable khan and engage him in debate to save the city from the attack of his troops was 13 years old and no more. Sons were married off before they turned two cycles, believing that by that time they had matured as men. At the same time, they followed the rules: if a son was born in the year of the snake, the bride could be a girl born in the year of the cow, chicken, or horse, but under no circumstances in the year of the monkey, tiger, or boar.

Thus, for young men, brides could most often be girls born in the year of the cow, horse, or chicken and aged between 13 and 17. Marriages at such an age were justified by the fact that, in the climatic conditions of Central Asia, girls matured earlier.

Throughout the 12-year cycle, people remembered unusual phenomena occurring in nature (severe frosts, droughts, famines, livestock deaths), as well as historically significant moments in social and political life, for example, in which year there were civil wars or attacks from external enemies and how much time had passed since then. The 12-year cycle was used to compare the severity or mildness of weather conditions in different years. According to the folk calendar, in the year of the dog, winter is mild; in the year of the wild boar, on the contrary, it is harsh and cold; in the year of the mouse, winter is average; in the years of the tiger and hare, it is even more moderate; in the year of the fish, summer is rainy, winter snowy; in the year of the snake, on the contrary, summer is dry, with no precipitation, and winter is moderate; in the year of the sheep, grasses grow well, snow is not deep; in the year of the monkey, summer is hot, and winter has little snow; in the year of the cow, summer is rainy, winter is moderate; in the year of the chicken, summer is hot, winter is moderate, etc.

People guided their daily lives by this knowledge. For example, in the year of the pig and the year of the fish, livestock was kept near the forest, knowing that during a cold, harsh, and snowy winter, there would always be feed there — the tops of shrubs, young tree shoots, etc. In the year of the snake and the monkey, farmers avoided sowing grain in dry and non-irrigated areas, as they anticipated a dry summer.

With the beginning of each new cycle, people would say: Adamdyn katary keldi — His cyclical year has arrived. It was believed that during this time, people were more prone to illness and death.

Now all these facts can be scientifically explained. It has been established that, on average, every 11.2 years, the Sun experiences the highest number of spots, flares, etc. This period is called the solar activity cycle, which is particularly strong every 80—90 years. At the end of each 11—12-year cycle, the Earth feels the effects of magnetic storms, during which auroras are observed (sometimes visible in moderate and even low latitudes) and strong deviations of the magnetic needle (notable disruptions in telegraph and radio communications), as well as increased thunderstorms, hurricanes, and downpours.

Doctors have established that during magnetic storms, most people suffering from ischemic heart disease, hypertension, and other conditions experience worsened health, hypertension crises, angina attacks, rhythm disturbances, weakness, decreased work capacity, etc.

Outbreaks of infectious diseases such as influenza, dysentery, and others also rhythmically follow the maximum of chromospheric outbursts on the Sun. In short, the empirical knowledge accumulated by the people over their centuries-old history is confirmed by modern scientific data. Indeed, the activation of natural processes associated with the periodicity of solar activity generally coincides with the beginning of the 12-year cycle. This was the case, for example, in 1984, the year of the mouse, at the beginning of which many adverse natural phenomena were observed.

The main source of knowledge for the people has always been their labor activity, during which experience was accumulated, causes and effects of phenomena were compared, and observations were generalized. Rationalistic views of the surrounding world were formed under the influence of such important discoveries for humans as the invention of tools for labor and hunting, better hunting techniques, the study of animal behavior to determine the edibility and medicinal properties of grains, herbs, and roots, and the emergence and development of animal husbandry and agriculture. Centuries-old observations and skills of the people were passed down from generation to generation: “Wise advice is the richest inheritance,” says a Kyrgyz proverb.

From disparate information about nature, pre-scientific knowledge of the Kyrgyz about the weather gradually formed. The observations and experiences of many generations of Kyrgyz were enriched by previously accumulated knowledge. By applying and testing their knowledge in practice, people gradually acquired increasingly accurate information about the nature surrounding them. Here, it seems appropriate to quote the words of A. I. Herzen: “If you do not chop the written word with an axe, the experience gained cannot be burned away with fire.”

V. V. Bartold, relying on the study of sources of ancient rituals, wrote that “... according to the Kyrgyz, fire was the purest element and destroyed all impurity.” The Kyrgyz said: “The Sun is a burning fire; the rays of the Sun warm the Earth.” This was confirmed by practice.

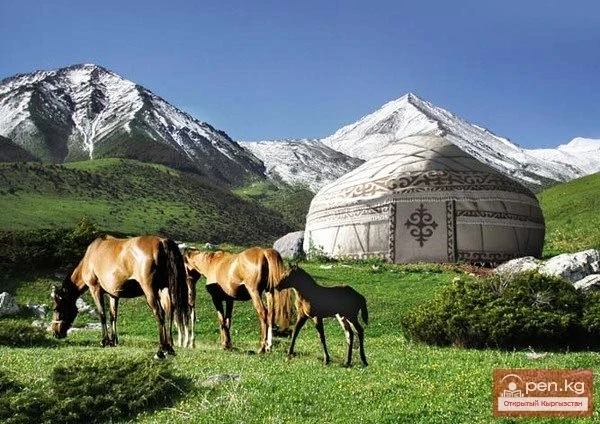

The immediate reason that compelled the Kyrgyz to constantly watch and observe the starry sky was the seasonality of work, the need to determine the time for sowing and harvesting grains, and the migration of livestock to the high pastures (dzhailoo) and back. It was believed that all pregnant mares should give birth approximately from April 1 to April 20, neither earlier nor later. Early births resulted in offspring that could not withstand the spring cold, while births occurring after April 20 meant that the young would not have enough time to strengthen before winter, which also led to death. Sowing of grain crops was not done before the second half of chyn kurana — March, as only by that time the soil warmed up and there was enough moisture in it.