The Basis of the Ancient Calendar.

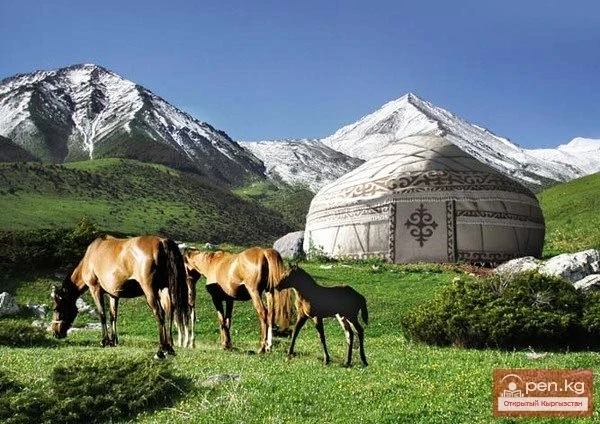

Even ancient hunters, observing the change of seasons and seasonal changes, learned to correlate them with periodic phenomena in nature. People knew that the river freezes in severe cold, that before the ice forms, trees shed their leaves, grass turns yellow and fades, and the days become shorter. The rhythm of people's lives and the cyclicity of their economy depended on the alternation of the seasons. People understood that after a certain period of time, all natural cycles repeat. They had no concept of the irreversibility of time; it was perceived as a moving circle of the eternal return of seasonal cycles.

Cyclicity and the closure of time is one of the central ideas of the worldview characteristic of many ancient cultures. It dates back to the ancient Indian Vedas, finding reflection in the concept of the World Wheel. In one form or another, this idea still exists in various teachings, shaping the worldview of many people in Eastern countries. In particular, the idea of cyclical time, opposing the arrow of time characteristic of ancient Mediterranean philosophy, leads to the perception of time not as irretrievably lost, but as accumulating, which exists both in the past and, to a certain extent, in the future. In such a perception, the sharp opposition of the present, past, and future loses significance, which is largely characteristic of the syncretic worldview prevalent in ancient Eastern philosophy, in contrast to the analytical one in ancient Western European thought.

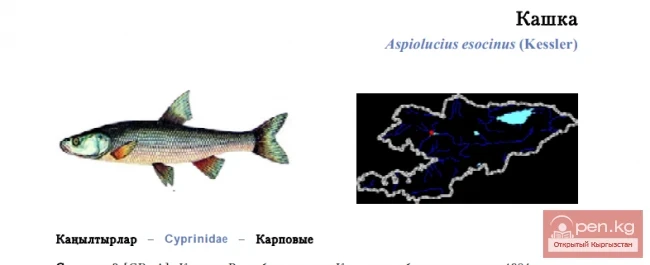

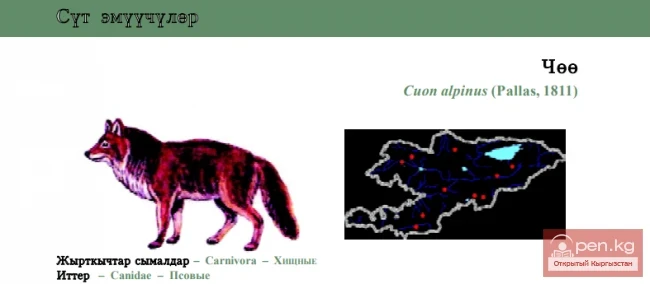

The concept of cyclical time became the foundation of the ancient calendar. Among the Kyrgyz, the calendar is divided into periods associated with hunting, animal husbandry, and agriculture. In the Kyrgyz folk calendar, five months are named after game animals: jalgan kuran and chyn kuran — male roe deer, bughu — male deer or maral, kulja — male mountain ram, teke — mountain goat. The names of these months reflect the connection with hunting — one of the oldest activities of the Kyrgyz. Their year was represented by an original 12-month cycle: jalgan kuran — February, chyn kuran — March, bughu — April, kulja — May, teke — June, bash oona — July, ayak oona — August, toguzdun ayi — September, zhetinin ayi — October, beshtin ayi — November, uchun ayi — December, and birdin ayi — January.

The materials collected in the early 1920s by well-known folklorists such as Belek Soltonoev, Kayym Miftakov, Aitkul Ubuikeev, and classics of Kyrgyz literature Alykul Osmonov and Tugelbai Sydykbekov, as well as academician K. Yudakhin and professor X. Karasaev, preserved the color of the past lifestyles of the Kyrgyz.

The beginning of the year was considered to be chyn kuran, when the spring equinox occurred, marking the period when the length of the day began to exceed the length of the night.

The calendar year consisted of four seasons: yaz — spring, jai — summer, kuz — autumn, kysh — winter. In the southern part of the republic, where settled Kyrgyz lived, the seasons were divided as follows: yaz — amal — March, coop — April, javza — May; jai — sary atan — June, aset — July, sumbulo — August; kuz — miyzam — September, akyrap — October, kave — November; kysh — jat — December, dalvy — January, and khut — February. As we can see, some month names are borrowed from Uzbek, Tajik, and other neighboring peoples of Central Asia.

The year consisted of 365 calendar days, with each season having 91 days, and one extra day (zhyldyn ajyralyshy) was left at the end of the old year and the beginning of the new year (March 20), which was not counted; March 21 was considered the first day of the New Year according to the Hijri calendar. On this day, wars ceased, and peace was restored among people.

The lunar calendar was 11 days shorter than the usual solar calendar. It corresponded more accurately to the seasons for the given locality. Kyrgyz farmers and herders oriented themselves according to it. Many holidays were also celebrated according to the lunar calendar.

Of the three winter months, the most difficult time for herders was from the 41st day of winter — childe; from the last decade of December to the beginning of February. This time was divided according to the severity of the cold into separate periods (ayaz). Each of them, according to the Kyrgyz, lasted 10–15 days. For example, temir ayaz — iron frost, meaning the harshest and strongest, occurred in January, muiyuz ayaz — horn frost, slightly weaker than the first, came in February, and at the end of February and the beginning of March it was replaced by kiyiz ayaz — felt frost, meaning weak, soft, with thaws.

Among the Kyrgyz, there is a legend about how the protector of the forty-first coldest winter day met a camel, a horse, a cow, and a ram. They began to discuss: "Who among us will first crush the cold?" They decided to concede the priority to the cow, as she was the oldest among them: "Let her crush the cold." To this, the horse objected: "Let me do it; I will crush it properly." But the other animals did not listen to the horse. The cow ran to the place where the cold lay and wanted to crush it with her hoof, but the cold slipped away, as the cow has a split hoof. Since then, the cold roams the earth.

The transition from pre-scientific thinking to scientific thinking was impossible without a settled way of life, a transition to agriculture and crafts, since scientific thinking, besides a fundamentally new way of generalizing knowledge, requires a fundamentally new way of fixing it — that is, the emergence of writing. The emergence of writing is associated with the development of agricultural culture. Czech and Soviet scholars Ch. Lokotka and V. A. Istrin proved that writing initially appeared in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and China, where agricultural culture was developed quite highly.

In the absence of scientific explanations of reality, elements of empirical knowledge, individual materialistic judgments about nature could be generalized based on imaginative thinking. Therefore, the personification of natural forces does not always indicate an idealistic position, as it is simply a way of generalization based on poetic thinking, poetic and mythological images. Empirical meanings at this stage of cognition and mastering reality begin to acquire relative independence, although they are still very closely linked to the practical activities of humans, who viewed all phenomena of reality through the lens of their influence on economic activities and the fates of people.

Ancient people instinctively recognized the unity of the world, its universality, and the interaction of its elements. Ignorance of the true laws of the environment and the immaturity of knowledge were expressed in that imaginary and fantastic connections replaced actual ones, prompting people to explain natural processes through the intervention of supernatural forces.

Thus, until a certain point, empirical knowledge, generalized in traditions, legends, and other folkloric forms, served the needs of primitive production, while the complexity of production called forth the necessity for precise knowledge.