Davan.

In the Fergana Valley, a powerful state emerged in the 1st millennium BC. In Chinese sources, it was called Davan.

Here is how scholars of that time described Fergana:

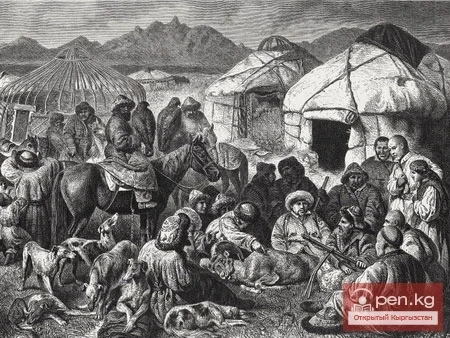

“The population consists of 60 thousand families — 300 thousand people; in the state of Davan, wine is made from grapes everywhere. Wealthy people store large supplies of grape wine, which can last for several years without spoiling. The people of Davan love grape wine, and their horses eat smusu (alfalfa). There are more than 70 cities in Davan. There are many stallions. When the stallions gallop, they become covered in reddish sweat. There are legends among the people that they descended from heavenly stallions. From Davan to the state of Anxi (Persia) in the west, the language of the inhabitants, despite significant differences, is similar, and they understand each other when they speak. They have sunken eyes and thick beards, and they are capable of trade, competing with each other for profit. Women are respected, and what a woman says is necessarily fulfilled by a man. They use both silk and lacquer, but they do not know how to cast iron products. Chinese poor people, fleeing from poverty, who ended up among the Davan, taught them how to cast weapons.”

The capital of the state of Davan was considered to be the city of Ershi. The surrounding city walls and watchtowers were built of brick.

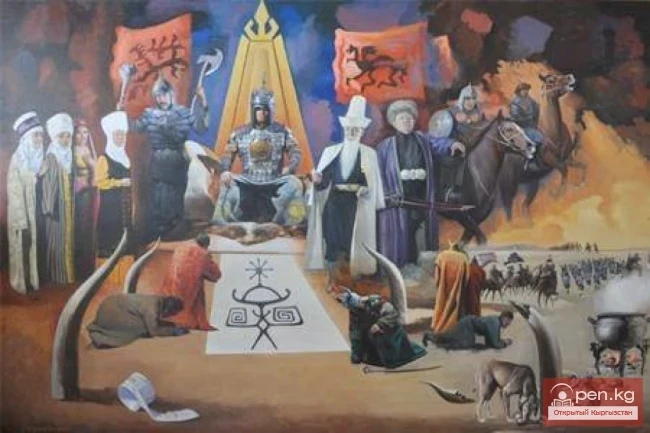

The state was ruled by a king. His main support was a council of elders, which included the nobility. The council of elders had significant powers in resolving important state issues: they would elevate and depose kings; declare war and sign peace treaties; establish relations with other states and receive ambassadors. They could even issue a sentence of death for treason against the king.

The state was characterized by a highly developed economy. The main occupation of the population was agriculture. They grew rice, wheat, grapes, cotton, and alfalfa. The grape wine produced by local winemakers could be stored for a long time without losing its taste. The local varieties of rice were considered the best in all of Central Asia at that time.

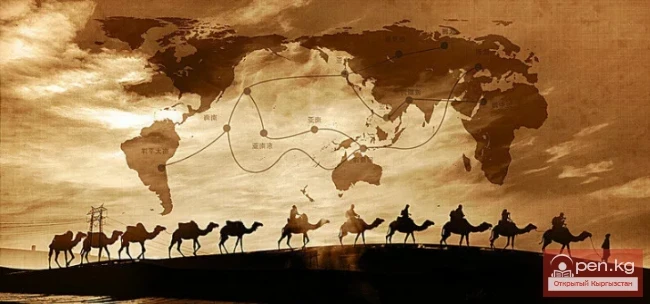

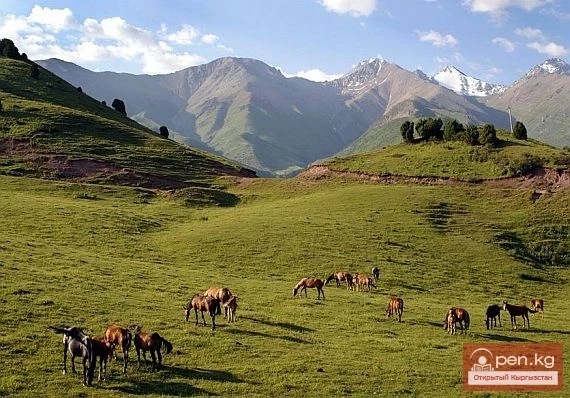

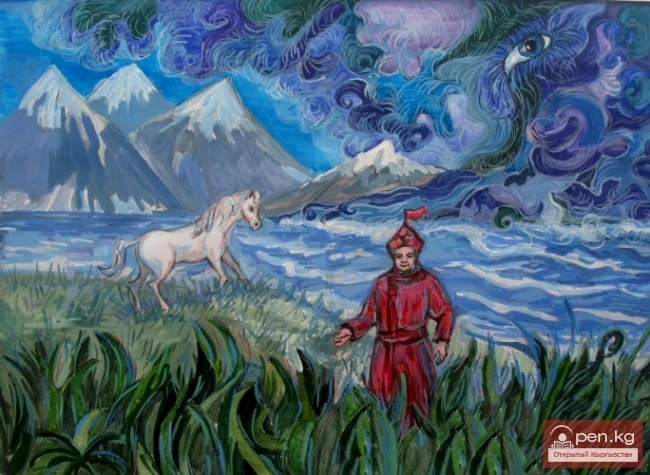

Fergana was famous worldwide for its stallions. It is no coincidence that Davan was called the land of "heavenly stallions".

According to a popular legend, the Fergana stallions descended from the horses belonging to the gods themselves. In stature, beauty of running, agility, and endurance, they had no equal. All horse experts, including those from neighboring and distant peoples, believed that there was no more valuable commodity and no more precious gift than Fergana stallions.

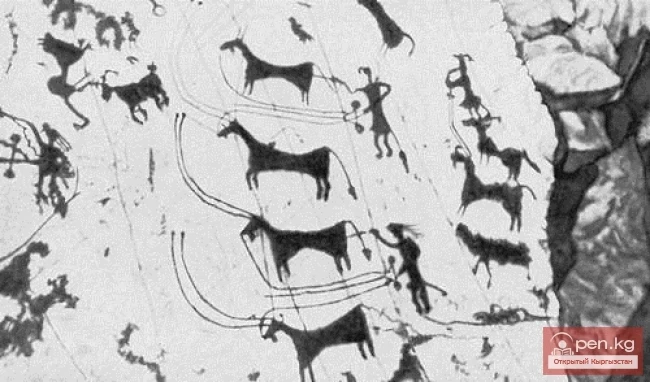

It is said that the famous Akhal-Teke horses of the Turkmen today are descendants of those Davan stallions. Images of the "heavenly stallions" have survived to this day on the rocks near the village of Aravan (Osh region).

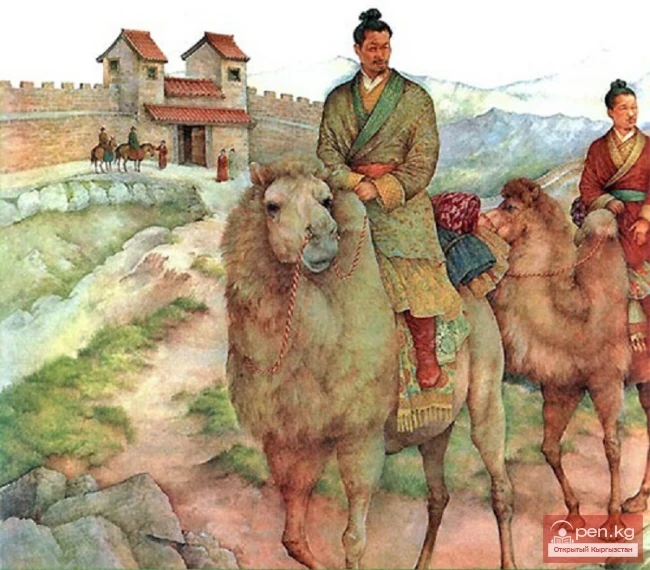

The invasion of the Chinese. To obtain the renowned stallions, the Chinese emperor sent an embassy to Fergana. The ambassador behaved arrogantly and demanded to be sold the stallions. Outraged by his behavior, the council of elders not only refused but also decided to execute the ambassador. For the Chinese emperor, this was the best pretext for war. He sent an army of 6 thousand cavalry and several thousand infantry to conquer Fergana. It was led by the general Li Guangli. Losing a large part of his army in the battle for the border city of Yu (located near the modern city of Uzgen), Li Guangli was forced to return to China. However, the emperor sent the general again on a campaign against the small Fergana, now at the head of a 100-thousand strong army. Li Guangli failed to capture the city a second time, so he left part of his army there and headed to conquer the capital - Ershi.

The defeat of Fergana. The king of the Davan, Mugua, was confident that the Chinese would come again and understood the hopelessness of fighting in open battle against the numerous Chinese armies. Hoping for assistance, he warned his neighbors — the powerful Kangju — about the impending Chinese invasion, and then ordered the population to stock up on water and food and to lock all city gates. The city prepared for defense.

For forty days, the Chinese besieged Ershi. To deprive the city of water, they diverted the river that fed the city in another direction, but the besieged residents dug deep wells and secured water again. The Chinese destroyed the outer walls surrounding the city, but before them rose other, even stronger, inner walls.

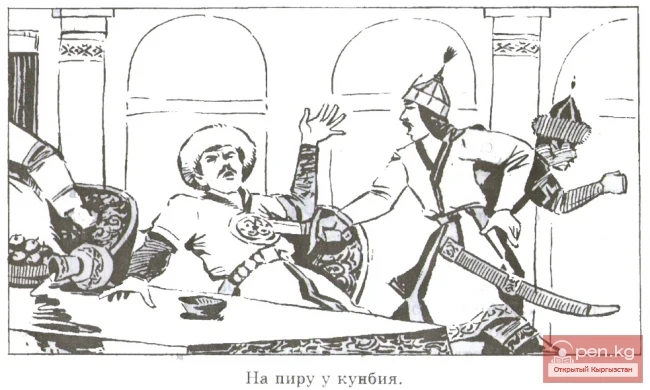

No one knows how much longer the conquerors would have to wait if there had not been traitors among the besieged. The nobleman Mo Tsai, who had long dreamed of power, along with his accomplices, killed the brave king Mugua. The council of elders requested peace from the Chinese in exchange for the king's head. Li Guangli agreed. According to the terms of peace, the Ferganese presented the Chinese with several dozen purebred horses and 3 thousand stallions. Mo Tsai ascended to the throne.

When the Chinese, returning home with their spoils, reached the border of the Davan state, they were attacked by the troops of the city of Yu. They killed part of the Chinese and captured many horses. However, Li Guangli managed to storm the city and behead its ruler.

In the struggle against the powerful China, Davan suffered defeat. The Chinese emperor also suffered great losses: 90 thousand of his warriors died in battles. Of the 3 thousand stallions, only a thousand made it to China.

After the departure of the Chinese, the council of elders sentenced the traitor Mo Tsai to death. The king of Davan became Mugua's younger brother — Chan Feng. In a short time, Fergana managed to regain its independence, and the Chinese rulers no longer interfered in its affairs.

In the 5th century, Fergana became part of the state of the Hephthalites, and in the 6th century, it was subjugated by the Turks.

The Kyrgyz in antiquity