From Shell and Copper - to Silver and Gold

The oldest means of monetary circulation in our region is considered to be, as in other Eastern countries, livestock, tools of production and labor. Archaeological studies of the earliest monuments of Central Asia, including Tian Shan, also show that cowrie shells - a type of marine gastropod mollusk - were used as money. These shells are oval in shape, resembling white porcelain, and were often used as ornaments. Due to their shape, they were also referred to as "snake heads" or "serpents." These shells are found in the Indian Ocean and the southern seas washing China. It is there that they first appeared as a form of money equivalent. The significance of cowries as one of the pre-monetary forms of money is eloquently illustrated by the Chinese character "bèi," which was adopted to denote them in China.

From a small area of the Maldives and Lakshadweep Islands, cowries spread as money to almost the entire Northern Hemisphere. They were known in India and Ceylon, Siam and Africa. They are found in ruins far from their homeland, in Slavic burial mounds, on the shores of the Baltic Sea, in ancient burial sites in Germany and England, Sweden and France. For millennia, this unremarkable shell reigned in the markets of many countries around the world...

By the second half of the 2nd millennium BC, bronze was known in China. It was then that the replacement of stone, bone, and clay items used as measures of value in the market began with coins made of more durable materials. Ancient Chinese money is known in the form of plates, bells, spades, hoes, and knives.

In Kyrgyzstan, near the station of Pishpek, a treasure of Chinese knife coins was accidentally discovered in 1972, which were in circulation in China from the 7th to the 3rd centuries BC. Unfortunately, they all spread into private hands, and only one knife coin was found by the collector G.I. Velichko. The ring-shaped top and the adjoining part of the handle are lost; only part of the handle and the blade remain, the edge of which is slightly curved inward. On one side of the blade, three characters are placed - the inscription, according to B.D. Kochnev, is very close to that published by the sinologist M.V. Vorobyov, - "standard coin of the state of Qi." Such coins were issued from the early 5th century BC until 221 AD, when the Qin dynasty unified the country and reformed the monetary system of China.

Another type of ancient Chinese coin, first recorded as money, is known as "wu-shu" in the Fergana region of Kyrgyzstan. Archaeologists find these coins in burials along with Chinese fabrics, mirrors, beads, and glassware - items of Chinese import. These items reached the cities and villages of Fergana via the Great Silk Road, which is believed to have been established after the well-known diplomatic mission of the Chinese ambassador Zhang Qian to the Western regions in the 2nd century BC.

However, the trade route existed earlier. This is evidenced, in particular, by the finds of wu-shu, which were issued during the reign of the Han dynasty (206 BC - 220 AD). Currently, more than 300 coins from burial mounds are known. They were found by G.A. Brykina in Northwestern Fergana, in the Batken and Laylak regions, in the burial sites of Tashravat, and are dated to 118 BC and the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. Some researchers believe that wu-shu reached Fergana no earlier than the 2nd century and were only used as ornaments. However, this conclusion seems debatable.

Read also:

Types of Higher Plants Listed in the "Red Book" of Kyrgyzstan (1985)

Species of higher plants removed from the "Red Book" of Kyrgyzstan (1985) Species of...

Types of Insects Listed in the 2004 IUCN RLTS Not Included in the Red Book of Kyrgyzstan

Insect species listed in the 2004 IUCN RLTS, not included in the Red Book of Kyrgyzstan 1....

Tourist Area Management Program

The project "USAID Business Development Initiative" (BGI), within the tourism...

The Poet Akbar Toktakunov

Poet A. Toktakunov was born in the village of Chym-Korgon in the Kemin district of the Kyrgyz SSR...

The title translates to "Poet Soviet Urmambetov."

Poet S. Urmambetov was born on March 12, 1934, in the village of Toru-Aigyr, Issyk-Kul District,...

Prose Writer, Journalist Djapar Saatov

Prose writer, journalist Dzh. Saatov was born on February 15, 1930, in the village of Alchaluu,...

Poet, Critic, Literary Scholar Omor Sooronov

Poet, critic, literary scholar O. Sooronov was born in the village of Gologon in the Bazar-Kurgan...

The Poet Tenti Adysheva

Poet T. Adysheva was born in 1920 and passed away on April 19, 1984, in the village of...

Poet, Prose Writer Medetbek Seitaliev

Poet and prose writer M. Seitaliev was born in the village of Uch-Emchek in the Talas district of...

The Poet Gulsaira Momunova

Poet G. Momunova was born in the village of Ken-Aral in the Leninpol district of the Talas region...

Poet, Journalist Barktabas Abakirov

Poet and journalist B. Abakirov was born in the village of Kum-Dyube in the Kochkor district of...

The Poet Subayilda Abdykadyrov

Poet S. Abdykadyrova was born in the village of Sary-Bulak in the Kalinin district of the Kirghiz...

Poet, Prose Writer Tash Miyashev

Poet and prose writer T. Miyashev was born in the village of Papai in the Karasuu district of the...

Prose Writer Kachkynbay (KYRGYZBAI) Osmonaliev

Prose writer K. Osmonaliev was born on March 5, 1929, in the village of Chayek, Jumgal district,...

Poet Abdravit Berdibaev

Poet A. Berdibaev was born on 9. 1916—24. 06. 1980 in the village of Maltabar, Moscow District,...

Prose Writer, Critic Dairbek Kazakbaev

Prose writer and critic D. Kazakbaev was born on June 20, 1940, in the village of Dzhan-Talap,...

Critic, Literary Scholar Abdyldazhan Akmataliev

Critic and literary scholar A. Akmataliev was born on January 15, 1956, in the city of Naryn,...

Poet Abdilda Belekov

Poet A. Belekov was born on February 1, 1928, in the village of Korumdu, Issyk-Kul District,...

Poet, storyteller-manaschi Urkash Mambetaliev

Poet, storyteller-manaschi U. Mambetaliev was born on March 8, 1934, in the village of Taldy-Suu,...

The Poet Baidilda Sarnogoev

Poet B. Sarnogoev was born on January 14, 1932, in the village of Budenovka, Talas District, Talas...

The Poet Sooronbay Jusuyev

Poet S. Dzhusuev was born in the wintering place Kyzyl-Dzhar in the current Soviet district of the...

The Poet Jumakan Tynymseitov

The poet J. Tynymseitova was born on 11. 1929—29. 07. 1975 in the village of On-Archa in the...

Types of Insects Excluded from the Red Book of Kyrgyzstan

Insect species excluded from the Red Data Book of Kyrgyzstan Insect species excluded from the Red...

Karymshakov Rakhym Karymshakovich

Karymshakov Rakhym Karymshakovich (1936), Doctor of Physical and Mathematical Sciences (1995),...

Prose Writer Kudaibergen Dzhaparov

Prose writer K. Dzhaparov was born in the village of Saz in the Sokuluk district of the Kyrgyz SSR...

Poet Karymshak Tashbaev

Poet K. Tashbaev was born in the village of Shyrkyratma in the Soviet district of the Osh region...

Poet Mariyam Bularkieva

Poet M. Bularkieva was born in the village of Kozuchak in the Talas district of the Talas region...

Prose Writer, Translator Bakan Sexenbaev

Prose writer and translator B. Sexenbaev was born on August 20, 1932, in the village of Burana,...

The Poet Kubanych Akaev

Poet K. Akaev was born on November 7, 1919—May 19, 1982, in the village of Kyzyl-Suu, Kemin...

Poet Dzhaparkul Alybaev

Poet Dzh. Alybaev was born on October 12, 1933, in the village of Birikken, Chui region of the...

Poet Dzholdoshbay Abdykalikov

Poet J. Abdykalikov was born in the village of Tashtak in the Issyk-Kul district of the Issyk-Kul...

Poet Mukambetkalyy Tursunaliev (M. Buranaev)

Poet M. Tursunaliev was born on January 11, 1926, in the village of Alchaluu, Chui region of the...

Poet Mederbek Akimkodzhoev

Poet M. Akimkodzhoev was born in the village of Bazar-Turuk in the Jumgal district of Naryn region...

Poet Akynbek Kuruchbekov

Poet A. Kuruchbekov was born on December 5, 1922 — November 29, 1988, in the village of Eryktu,...

Poet, Prose Writer Dzhenbap Mambetaliev

Poet and prose writer D. Mambetaliev was born on December 18, 1938, in the village of Ottyk,...

The Poet Turar Kodzhomberdiev

Poet T. Kodzhomberdiev was born on October 15, 1941—January 30, 1989, in the village of...

Chorotegin (Choroev) Tynchtykbek Kadyrmambetovich

Chorotegin (Choroев) Tynchtykbek Kadyrmambetovich (1959), Doctor of Historical Sciences (1998),...

Salamatov Zholdon

Salamatov Zholdon (1932), Doctor of Physical and Mathematical Sciences (1995), Professor (1993)...

Poet Mayramkan Abylkasymova

Poet M. Abylkasymova was born in the village of Almaluu in the Kemin district of the Kirghiz SSR...

Critic, Literary Scholar, Poet Kachkynbai Artykbaev

Critic, literary scholar, poet K. Artykbaev was born in the village of Keper-Aryk in the Moscow...

Poet, Prose Writer Isabek Isakov

Poet and prose writer I. Isakov was born on September 1, 1933, in the village of Kochkorka,...

Poet, Prose Writer Mar Aliev

Poet and prose writer M. Aliev was born on July 14, 1932, in the village of Kochkorka, Kochkorka...

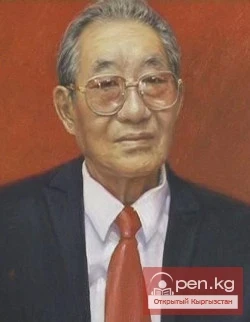

Prose Writer, Poet Junay Mavlyanov

Prose writer and poet J. Mavlyanov was born in the village of Renzhit (now the village of...

Poet Esengul Chopieva (E. Urmatvek)

Poet E. Chopieff was born on June 27, 1937, in the village of Kyzyl-Bairak, Kemin district, Kyrgyz...

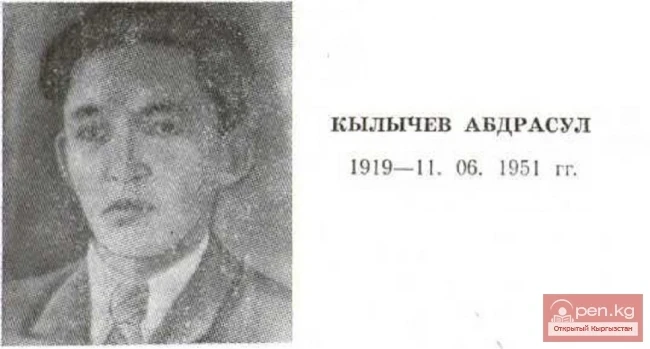

Poet, Prose Writer Abdrasul Kylychev

Poet and prose writer A. Kilychev was born in the village of Orto-Sai near the city of Naryn in...

The Poet Smar Shimeev

Poet S. Shimeev was born on November 15, 1921—September 3, 1976, in the village of Almaluu, Kemin...

Poet, Translator Orozbay Sulaymanov

Poet and translator O. Sulaymanov was born on February 20, 1928, in the village of Novorossiysk,...

Population of Kyrgyzstan as of January 1, 2013

Population of Kyrgyzstan Thanks to the fundamental changes that occurred in Kyrgyzstan after the...