Questions of Historical Interpretation.

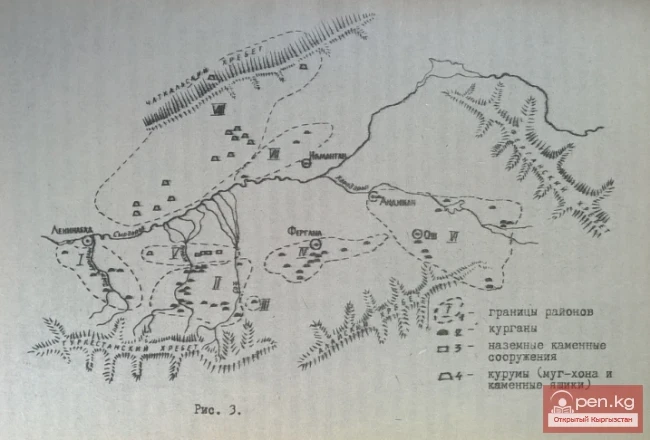

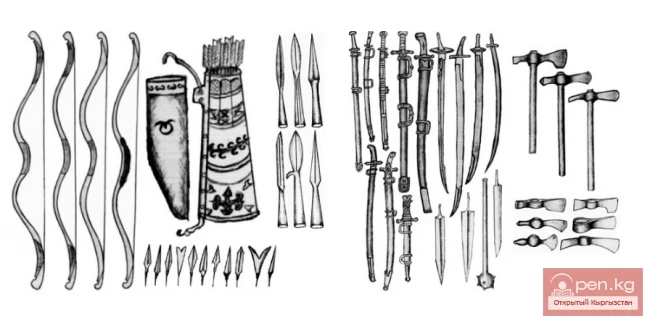

Currently, only preliminary conclusions can be made regarding the interpretation of the zoning of the examined monuments. In the preceding period - in the second half of the 1st millennium BC - the territory of Fergana was characterized by uniform burial monuments of the Eilat culture - Aktamsk type (6th-3rd centuries BC). In the next stage, during the Davani period (2nd century BC - 5th century AD), instead of one type, one culture, at least five local groups of nomadic monuments emerged. Among them, only the above-ground stone crypts of the northwest and the earthen burials have local roots. Without delving into the details of the contentious issue regarding the origin of the catacomb and subsoil burials of Fergana, we will only note that during the Davani period, there was a breakdown of the previously existing boundaries of nomadic settlement from the Saka period.

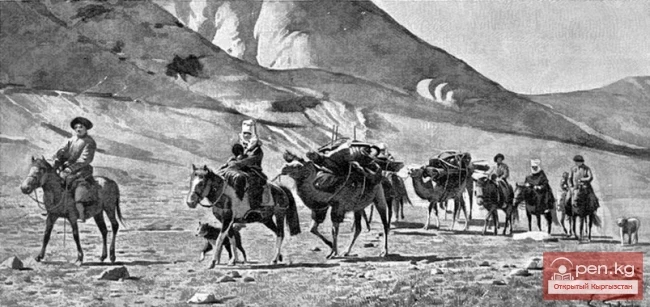

All these events are at least partially related to the external invasion of nomads, judging by the information from Chinese chronicles about the movements of the Yuezhi tribes at the turn of the 2nd-1st centuries AD through Davani. It should be noted that the main plain and foothill areas of Fergana have long been inhabited by farmers. With the arrival of newcomers, new areas of settlement must have formed, and they had to deal with a sufficiently strong Davani state, which, according to written sources, maintained independence and continuous development for about 600 years - from 125 BC to 420 AD. It is necessary to consider that the main archaeological cultures and local groups we examined existed approximately at the same time - from the 2nd-1st centuries BC to the 4th-6th centuries AD. At the same time, all scholars agree that their maximum spread occurred in the 1st-4th centuries AD.

The examined burial grounds also functioned for a long time. The synchronism of their existence with the Davani state is beyond doubt. In this regard, the question arises about the nature of the relationships between the nomads and the settled population of Davani. There is no direct information in the sources about this.

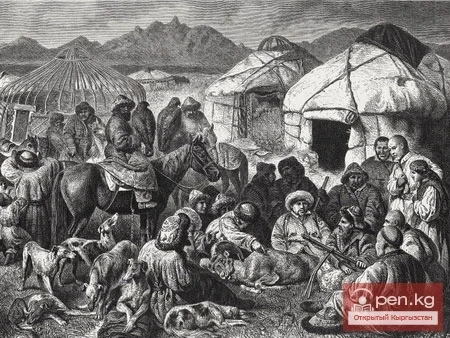

The analysis of the mapped monuments, highlighted archaeological cultures, and local groups allows us to speak about the stability of the territorial boundaries of these groups and the stability of their areas. It is likely that the areas of some groups reached optimal sizes at that time and did not change. To understand the reasons for the coexistence of different groups of nomads and the Davani state over a long period, we turn to the only possible ethnographic materials about the settlement of Kyrgyz tribes on the periphery of Fergana in the 19th - early 20th centuries. There are simply no other data. When comparing our distribution scheme of monuments with the ethnographic map compiled by S.M. Abramzon (1963), it turned out that the territory occupied by the Ichkiliks, from Laylyak to Naukat, quite distinctly coincides with the area of the II district, with the territory of the Karabulak culture. The lands to the east were occupied by the Avdegine tribes, who lived up to the Fergana ridge. It is here that the monuments of the VI district are widespread. More notably, to the west of the Ichkiliks, the valley of Khoja-Bakirgan was inhabited by the Konurat tribe, within the same borders as the nomads of the I district. According to ethnographers, the Konurat tribe stands out among the Kyrgyz for its distinct origin. Finally, in the north of Fergana, in the VI district, another Kyrgyz tribe - Bagysh - lived. In these four cases, we are dealing with different clan-tribal groups. Thus, we note the coincidence of the areas of three to four groups of nomads from the 1st-5th centuries AD and Kyrgyz tribes from the 19th - early 20th centuries. Naturally, no direct connection can be traced between them. The coincidence of areas is observed under unchanged geographical conditions in the 1st-2nd millennia and with the proximity of forms of semi-nomadic pastoralism. Moreover, from these comparisons arises the tempting possibility of seeing the Yuezhi as one of the distant ancestors of the Ichkiliks. If it is possible to finally substantiate this hypothesis regarding the affiliation of the subsoil burials of the Karabulak culture to the Yuezhi tribes.

Ethnographic data characterize the fragmentation and greater complexity of the clan-tribal structure of the Kyrgyz tribes in the south. Thus, the division of the Ichkiliks consisted of 10 equal tribes. Each tribe and clan migrated in a strictly defined territory. Territorial community was one of the essential properties of the clan-tribal structure. The tribes at that time were not homogeneous and sometimes included alien groups.

Initially, the Kyrgyz maintained independence and acted as allies of the Kokand Khanate; however, the Kyrgyz tribes fell into dependence and were subordinated, although some tribes living in hard-to-reach isolated areas retained a certain independence.

At the same time, the Kyrgyz rulers of clans and tribes often intervened in the affairs of the khanate and sometimes influenced the change and promotion of khans.

The position of the Kyrgyz tribes within the Kokand Khanate and the nature of the relationships between them can be reasonably regarded as an ethnographic model that allows understanding the essence and mechanism of processes that occurred in ancient times.

It can be assumed that the coincidence of settlement features in the specified periods reflects optimal conditions for pastoralism in these areas and a close tradition of securing rights to certain pastures and clan-tribal territory as a whole. These favorable and optimal conditions for settlement likely formed at the beginning of the 1st millennium AD.

The highlighted groups (districts) likely correspond to separate clan-tribal subdivisions of nomads. In the history of Davani, these tribes evidently also played a significant role. It can be imagined that the political situation in Davani was more complex than is usually assumed. All of the above provides grounds to hypothesize that the stability of the boundaries of local groups of nomads was determined by some forms of contractual relations of alliance or dependence (which remains unknown to us), which defined the living conditions of nomads on the periphery and within Davani. By the way, it is worth recalling that the sources contain direct references to allied relations with neighboring tribes - the Usuns and Kangju, who sided with Davani during the invasion of Han troops in 104-99 BC. This data cannot be ignored when studying the nature of the relationships between the farmers of Davani and the nomads.

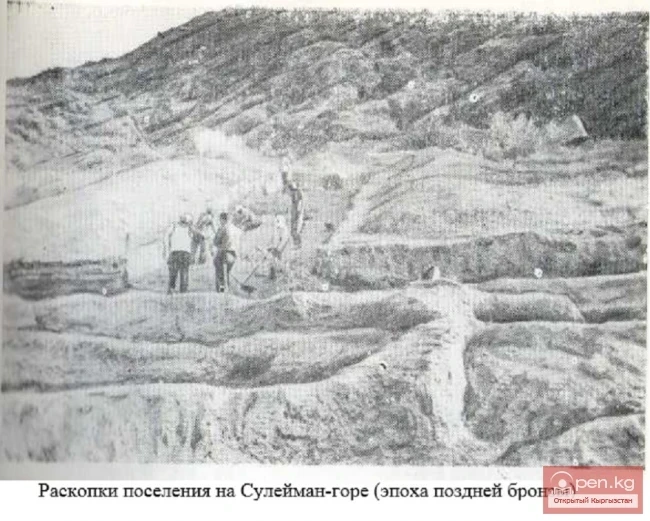

Zoning of Excavations in the Fergana Valley