Recent Research

Extensive research work on Issyk-Kul in the 1920s was conducted by a native of Kyrgyzstan, the subsequently well-known orientalist P. P. Ivanov. He was the first to approach the study of the underwater mysteries of Issyk-Kul with expertise and professionalism. After surveying the coastal waters of the lake by boat, P. P. Ivanov registered underwater ruins of settlements in the areas of Chon-Koysu, the Tyup Bay, and Koy-Sary. He attributed them to a single time period, believing that they were remnants of medieval monuments. Ivanov created a plan of the broad shoal in the Chon-Koysu area, marking the underwater ruins located on it: brick and stone walls, wooden flooring, which he identified as ceilings of underground structures, stone pavements resembling streets or floors of buildings, millstones, fragments of ceramic dishes, bones, etc.

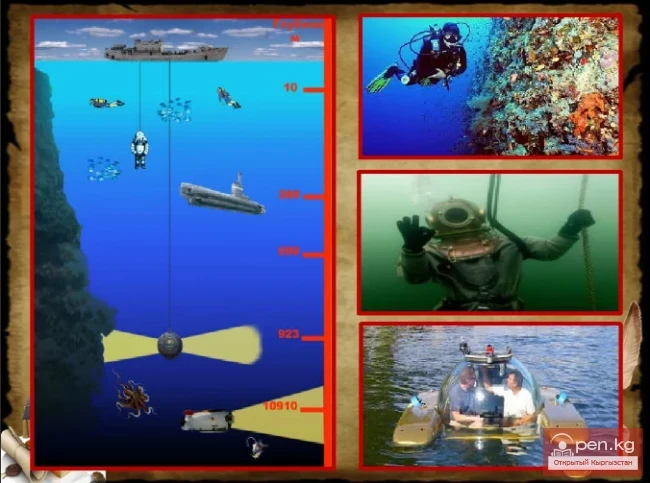

A special task of researching the underwater monuments of Issyk-Kul using diving techniques of the mid-20th century was set by archaeologist D. F. Vinnik; having undergone special training with one of the founders and enthusiasts of underwater archaeological excavations, Professor V. D. Blavatsky, D. F. Vinnik began systematic archaeological surveys of the underwater monuments of Issyk-Kul in 1959. Over two years, a small team led by D. F. Vinnik surveyed parts of the northern and eastern coastal waters of Issyk-Kul.

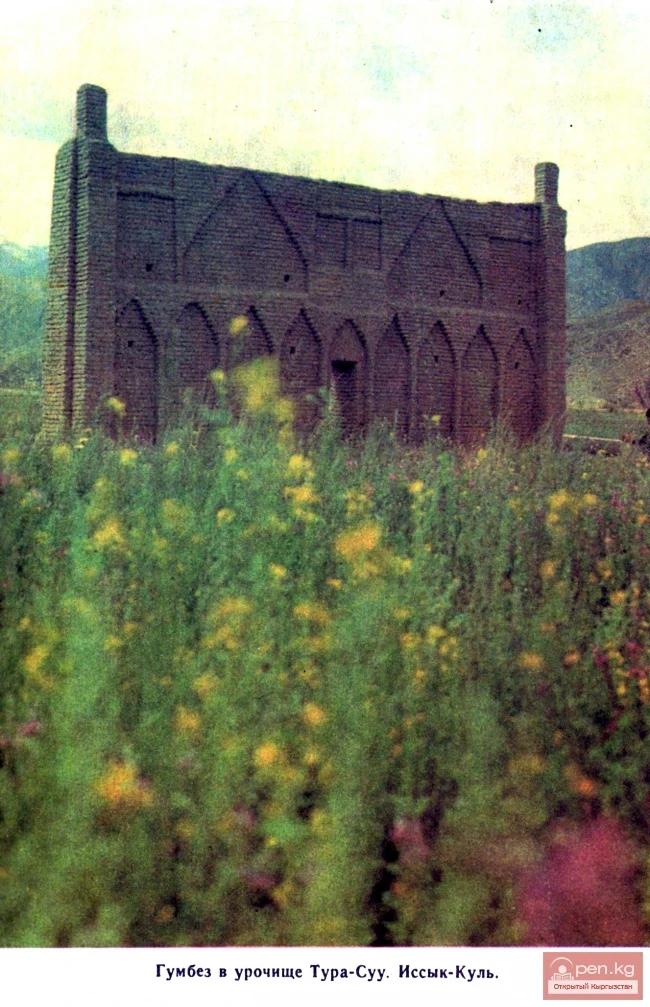

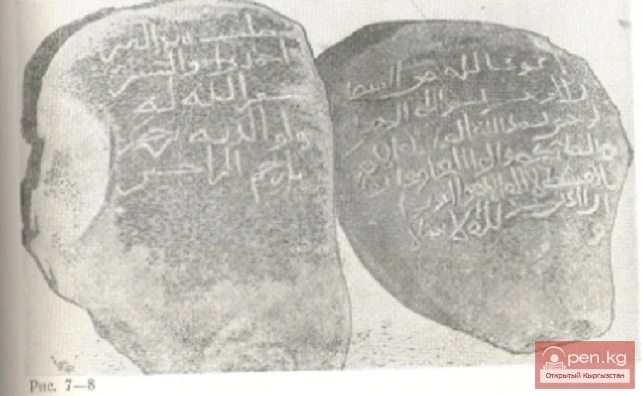

It was convincingly proven that there are settlements underwater not only from the 12th to 15th centuries but also from several earlier periods, starting from the 8th century A.D. At the same time, underwater surveys in the Koy-Sary area showed that as a result of the lake's shallowing, previously submerged ruins had emerged on the shore. This allowed for a shift to traditional excavations of above-ground monuments in this area.

From that time on, D. F. Vinnik ceased underwater archaeological work and subsequently, in the 1960s to 1980s, focused on studying the monuments of ancient nomads and medieval settlements only on land, primarily in the foothill zone of Issyk-Kul.

However, underwater monuments continued to stir the imagination and beckoned for new research. A new phase of underwater research began in the summer of 1985 with the work of the Issyk-Kul Historical and Archaeological Team.

The impetus for this was a new encounter with antiquities on the shore of the lake three years prior—in 1982.

Trophies of Issyk-Kul

The sun was already setting when we—the historical and archaeological team of the Institute of History of the Academy of Sciences of Kyrgyzstan—decided to stop on the southern shore of Issyk-Kul, near the village of Darkhan. We had barely set up camp when an elderly man arrived at our tents in a cart. War veteran Toytobai Maaliev came with his wife.

“Archaeological expedition,” he read on the vehicle. And immediately asked, “Are you interested in underwater finds? I can show you.”

And Toytobai recounted how he had fished here a few years ago from a boat, about 20-25 meters from the shore—he pointed to the middle of the bay. “Suddenly I saw some unusual-shaped objects in the water. I jumped in. It was shallow—about one and a half meters. I pulled out—metal objects. At first, I thought it was gold, but then, back home, I realized it was bronze. Well, let’s go—I’ll show you.”

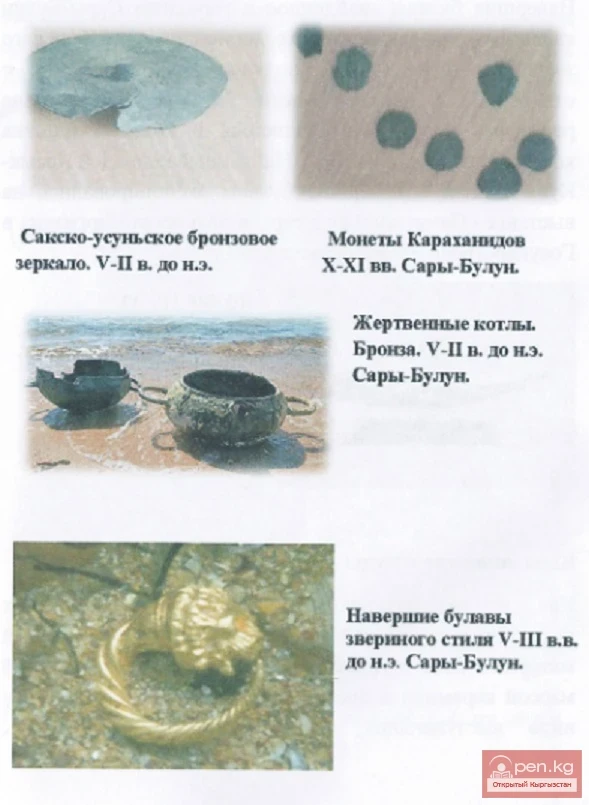

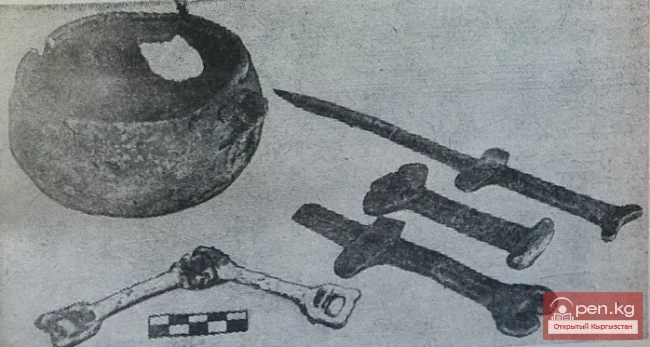

We were still somewhat skeptical about our luck, but we went to his home in the village of Darkhan, and just fifteen minutes later, we were holding fragments of two bronze daggers and a bronze kettle with a small spout. When the owner also handed us a flattened fragment of a large cauldron, all doubts vanished—it was a find of very ancient origin. Before us lay fragments of items that had been cast at least two and a half thousand years ago.

The first dagger had a broken end, but the most important and valuable parts were preserved; a decorative pommel, a butterfly-shaped cross-guard, and a double-edged ribbed blade. The handle had three vertical grooves on both sides. The most remarkable feature that made the dagger unique was the artistic pommel, crafted in the shape of two mountain goat heads in a mirrored image—as if touching each other’s napes with their twisted horns.

The second dagger was generally similar to the first, with a block-shaped pommel, a butterfly-shaped cross-guard, and a double-edged ribbed blade, though it was broken at the very base. The handle also had three vertical grooves on both sides.

We meticulously recorded all the dimensions of the finds, artists made sketches, and photographers took pictures. The smallest details could be useful in identifying analogies and determining chronology.

Already in Frunze, while reviewing publications and numerous archaeological tables, we found the closest similarities to the dagger, approaching identity—this was a chance find in the Chui Valley by A. K. Kibir and the dagger that is part of the Issyk treasure, found by K. A. Akishev near Almaty (the latter dated to the 6th-4th centuries B.C.).

The bronze ritual kettle with a spherical body and massive walls did not go unnoticed either.

The rim of the kettle slightly protruded, and beneath it was a spout that had been preserved intact. The kettle had no handle; instead, there was a gaping hole at a 90° angle from the spout on the body of the kettle. The handle had apparently been broken off long ago when the vessel was used for its intended purpose. Similar items had been found repeatedly in the area of the former settlement of the Saka and Sarmatians.

The fragment of the large sacrificial cauldron was unremarkable, lacking the ornaments and decorations that sometimes distinguished sacrificial cauldrons from the Saka period.

The Darkhan finds of 1982 enriched the Saka collection of the exhibition at the museum of the Institute of History of the Academy of Sciences of Kyrgyzstan. But their significance is not only in this. They once again proved that Issyk-Kul Lake holds many unsolved mysteries. An underwater archaeological search was necessary. Moreover, the main task of our team was to gather materials for the next volume of the “Collection of Monuments of History and Culture of the Kirghiz SSR. Issyk-Kul Region,” which naturally meant the need to account for the submerged monuments as well.

Secrets of Issyk-Kul Lake