The Fergana Miracle

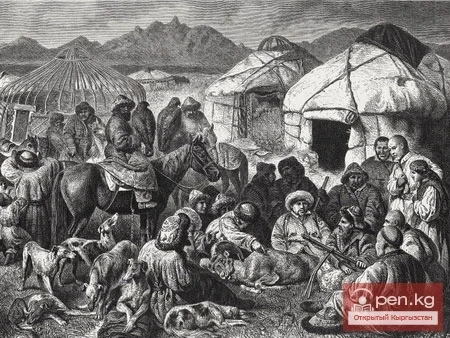

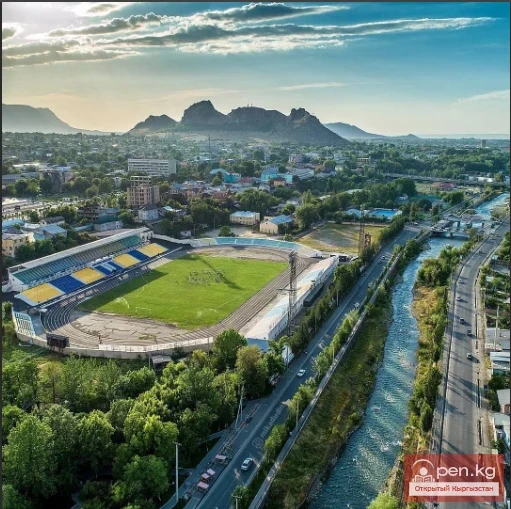

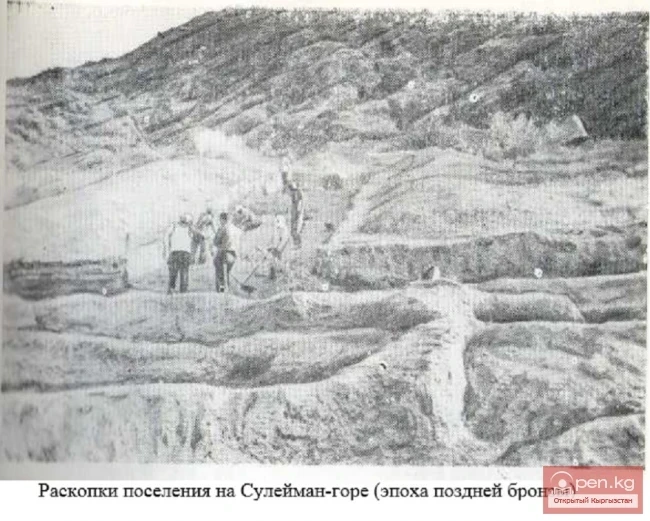

Dawan of that time (Fergana, including the south of Kyrgyzstan) represented a strong state formation, a union of "oasis-cities" led by a local dynasty. The Chinese were accustomed to the idea that real (not felt) buildings, canals, and developed agriculture existed only in their homeland, while neighboring lands languished in barbaric ignorance. Dawan pleasantly surprised them. No, it didn’t just surprise them — it shocked them!

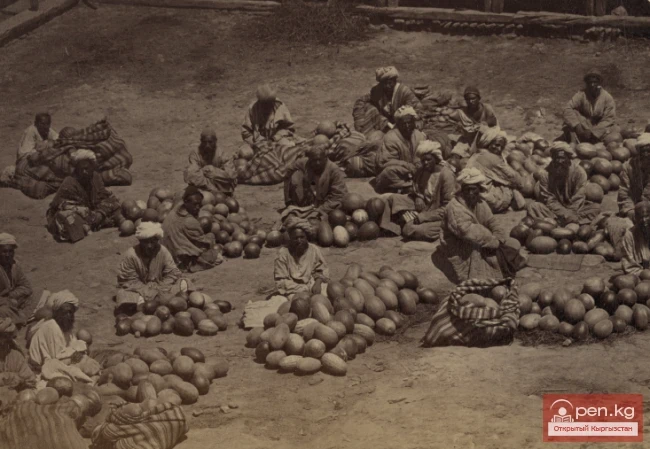

They discovered well-tended fields with barley, millet, and wheat. To their astonishment, there were lush gardens where radishes, leeks, and their beloved garlic grew!

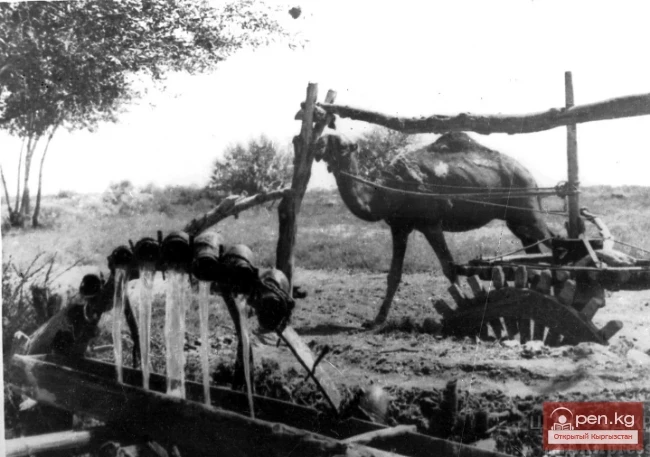

Real canals with brown water, bordered by shady groves and gardens! A web of roads connected bustling cities, sheltered behind thick walls with mighty towers, with the palaces of rulers and nobles. And everywhere — on the hills, along the banks of canals, by the roads — clusters of fortified rural estates resembling small fortresses.

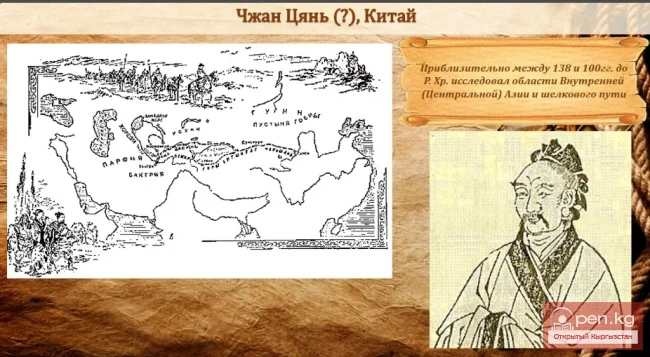

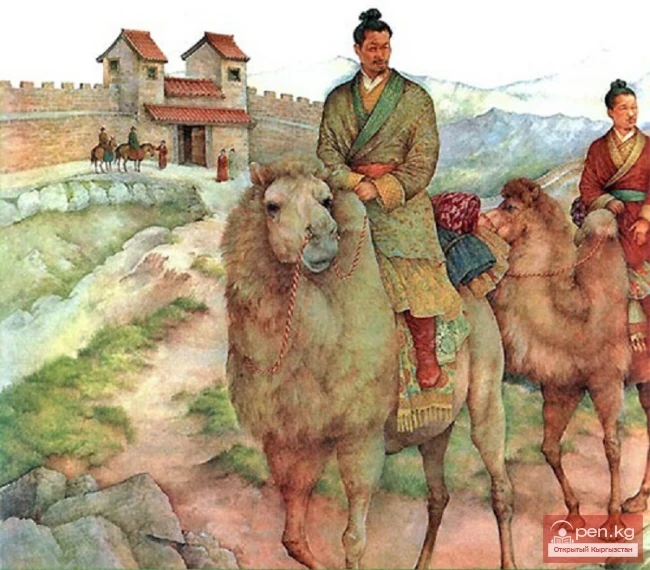

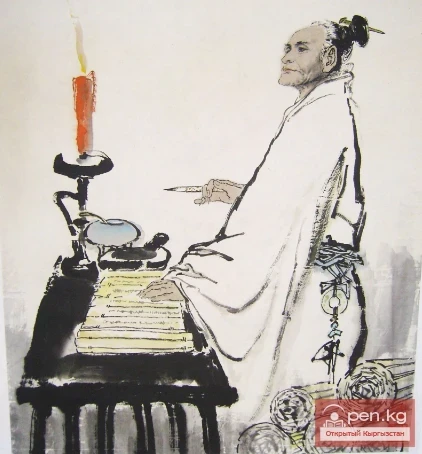

The king of Dawan had heard of the wealth and power of the distant Han country and was ready to establish friendly relations with it. The great diplomat Zhang Qian immediately realized the benefits such a friendship promised. Even the king of Dawan and his nobility were dressed in coarse, faded fabrics made of wool and cotton. "And if they see our silk," thought Zhang Qian, "all their riches will be ours."

No caterpillar or any other insect played such a role in the fate of nations as the mulberry silkworm did in the fate of "Zhong Gu" — the Middle Empire. Even in the times of Cheng Tang — the founder of the first Shang-Yin kingdom (18th century BC), offerings were made to the spirits of silkworms. Silk is a purely Chinese invention. It has accompanied the lives of the inhabitants of the Celestial Empire throughout its long history.

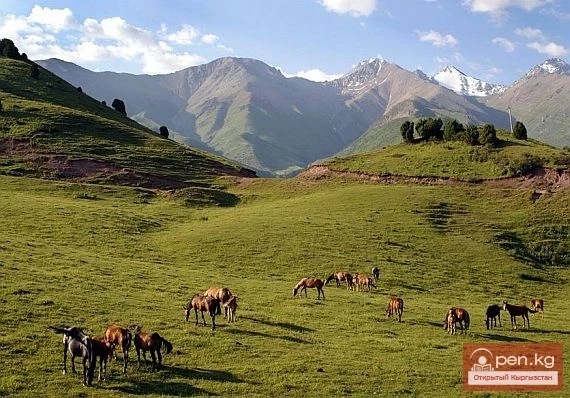

Yet here in Dawan and all other countries, Zhang Qian saw not a single mulberry tree. True, there were plants here that one would not find in the Celestial Empire. Zhang saw vast emerald-green patches — a solid carpet of unknown succulent grass. Horses crunched on it with such appetite that one wanted to try it themselves. The locals pronounced the name of the grass in their dialect: the Chinese ear recorded it as "mu-su." He was also told that the grass was so tasty and nutritious that animals overindulge in it and can die from bloating.

Later, he would take seeds of this wonderful grass — alfalfa — back to his homeland...

But even more astonishing to the travelers was a certain vine, twining between specially dug posts on stretched trellises. Among the thick, sprawling leaves hung huge beads gathered in clusters, while other berries were shaped like nipples. Some were yellow and transparent, others were pink, and still others were blue, almost black. And when the travelers tasted the drink made from these berries, they were utterly delighted: it had a marvelous taste and a fairy-tale aroma! And it felt much more pleasant on the head than the stinky gaoliang vodka.

Thus, for the first time in his life, a Chinese man saw a grapevine — a wonder of nature, and tasted wine — a gift from the gods... Zhang Qian would be the first to introduce his great homeland to this ancient agricultural culture...

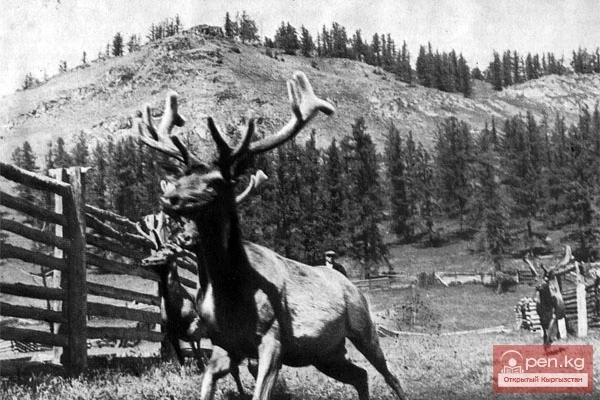

And another wonder was discovered here by Zhang Qian — the splendid stature and agility of the horses. He wrote: "These horses sweat blood and come from the breed of heavenly horses." After him, for centuries, the main demand of the Han court from the Dawan people was to supply the empire with argamaks — "heavenly horses."

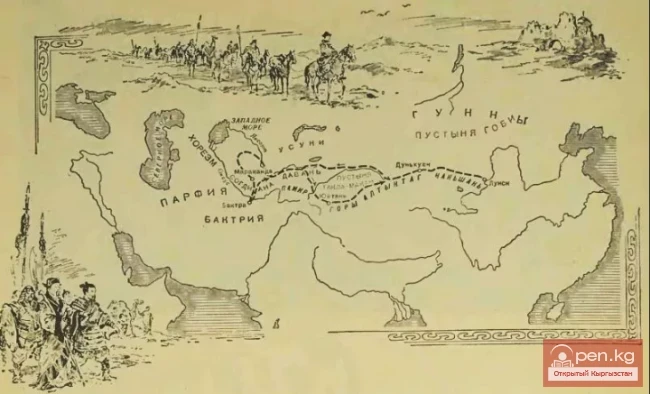

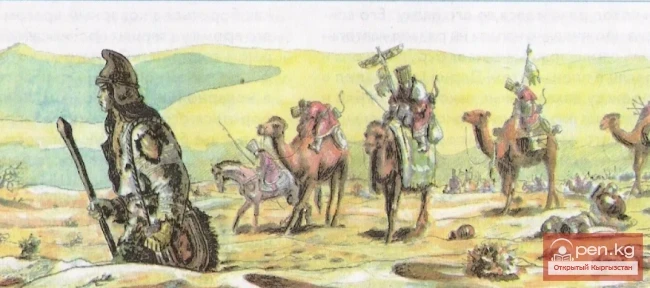

Zhang Qian visited the Great Yuezhi. Here he faced misfortune. Homeless nomads — fugitives who had fled to the ends of the earth from the vengeance of the Huns — now owned the richest agricultural lands — Sogdiana and Bactria.

Their carefree, well-fed life had spoiled them; they did not want to hear about any war with the Huns.

Not achieving diplomatic success, Zhang Qian gained in another way: traveling through the lands of the Yuezhi, he visited both countries and introduced them to his compatriots. Moreover, from experienced people, Zhang heard about other lands: Yancai (Zaaralye), Kangyu (Central Asia), Anxi (Parthia), and even Linjian or Da Qin (the Roman Empire).

The most astonishing thing here is this: how could Zhang Qian gather this invaluable information without knowing the language?...

Only after thirteen years did the great traveler return to China.

The Feat of Zhang Qian