The economy of Kyrgyzstan during the era of Turkic states experienced syncretic development (a combination of the advantages of nomadic and settled lifestyles).

Political consolidation within the Turkic states, culminating in the Karakhanid Kaganate, opened up wide opportunities for the development of the medieval economy of Kyrgyzstan.

The movement of peoples, the Great Silk Road, trends towards sedentarism among nomadic Turks, skills in agriculture, animal husbandry, and crafts, as well as close interaction among a multilingual, multiethnic, and multiconfessional population found fertile ground for development in the strong khanates. Moreover, far-sighted khans implemented economic and financial reforms that, under centralized governance, contributed to the improvement of the economy.

In the development of Kyrgyzstan's economy (especially in agriculture, urban life, and crafts), a significant role was played by the Sogdian migration to Semirechye, which occurred in two stages from the VI to the XI centuries. Almost all agricultural regions, in the river valleys along the northern branch of the Great Silk Road (Issyk-Kul — Chui — Talas — Chach), had Sogdian settlements and even cities of purely Sogdian origin. Many Sogdians also lived in large cities such as Suayb, Nevaket, Taraz, Atlaq, and others.

A classic characterization of the economy of Kyrgyzstan in the Middle Ages can be seen in the example of the Karakhanid period. This was a time of the highest achievements of the Kyrgyz population of the Turkic era in all spheres of life. The era is primarily marked by significant growth in urban life. Urban life, which had been widespread since the times of the Western Turks (VI century), received further development under the Karakhanids. As a result, the face of the Chui Valley changed significantly, not to mention Fergana.

During this time, cities were surrounded by rural settlements — rustaks, powerful walls were built around them, and castles and citadels of khans and wealthy nobles arose to protect the cities' possessions and the borders of small oases. Within the cities themselves, alongside the shahristan, characteristic of that period of urban civilization, trade and industrial suburbs, rabads, began to develop. The number of urban-type settlements increased during this period in areas that had previously been inhabited only by nomads. For the first time, cities even appeared in the Tian Shan mountains. For example, between the cities of Atbash on Tienir-Tuu and Barskhan on Issyk-Kul, a whole network of settled settlements arose in the Kochkor and Jumgal districts along the Naryn River.

At the same time, another process was occurring — the number of small cities decreased. In exchange, the sizes of larger urban centers increased, growing due to their trade and industrial suburbs. This process is particularly evident in the Fergana, Talas, and Chui regions. During the heyday of the Karakhanids, cities such as Suayb, Hamukat, Selji, Susy, Kul, Tekabket, Kulan, Asbara, Nuzkent, Kharran Juvan, Jul, Saryg, Koylyk, Kirmirau, Balasagun, Nevaket, Kerminket, Yakakent, Barskhan, Taraz, Atlaq, Atbashy, Osh, Uzgen, Medva, Kasan, Aksyket, Ranjit, Khaylama, Nauken, Izbaskent, Shikyt, Bisket, Salat, and Kheftedek existed. There were also cities whose names have not survived. Arab travelers counted more than 80 cities in Semirechye and the Issyk-Kul-Naryn region, and more than 40 in Fergana.

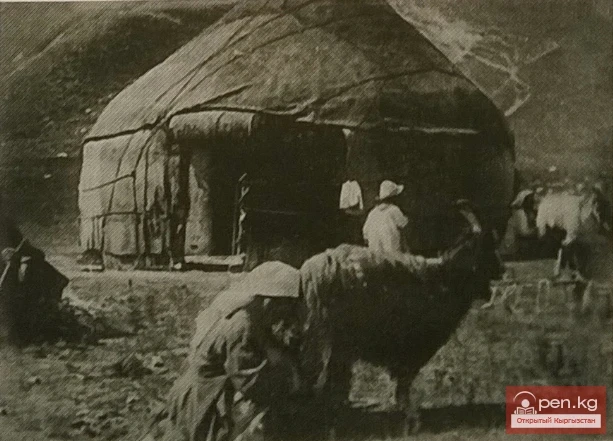

During the Karakhanid era, the main occupations of the population remained agriculture and animal husbandry. However, these sectors were significantly improved. On one hand, many agricultural skills of the settled population were borrowed by the herders, and their skills were adopted by the farmers. This process led to a tendency for the frequent emergence of mixed economies among the bearers of both types, which implied the formation of a majority of semi-settled, semi-nomadic economies in most states. Consequently, large wealthy farmers developed industrial animal husbandry and subsequently wholesale trade. On the other hand, both agricultural and pastoral cultures were significantly influenced by incoming migrants: Sogdians, Chinese, and various Turkic and Mongolian tribes from the East.

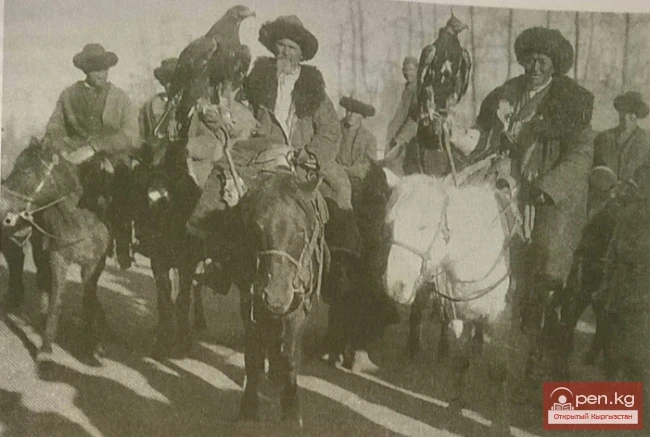

During the Karakhanid period, the same types of animal husbandry that have survived to this day were primarily practiced. However, according to sources, for example, from "Hudud al-Alam" (10th century), sheep, cows, and horses were considered the main types of livestock among the Yagma, Karluk, Chigili, Tukhsi, and Kyrgyz tribes. Describing the abundance of livestock, the traveler Ibn-Hawqal was surprised by the fact that, in his opinion, there were practically no pastures free of livestock between the cities.

The development of trade is eloquently evidenced by ceramics — a common and mass material from the ruins of ancient urban settlements. The peak of trade along the Great Silk Road occurred during the Karakhanid period. The middle and southern branches of the Silk Road passed through Kyrgyzstan, each of which branched out within the territory of Kyrgyzstan. Along the Great Silk Road, a whole network of settled agricultural, postal, and other settlements grew, and cities emerged where bazaars thrived. The city of Osh stood out particularly. In the Middle Ages, Osh was the center of economic ties, trade, and cultural exchange: it had numerous mosques, madrasas, bazaars, caravanserais, and was the residence of the emir. According to some indirect data, there was a large library in Osh, and great thinkers such as Ali Mansur al-Oshi, Mahmud Yugnaki, and Ahmed Fergani lived and worked there. The three gates of the city were known throughout the East and West: the Mug-Kede gate — the gate of the fire-worshippers' temple, the Ak-Bura river gate, and the Suleiman mountain gate. In the vicinity of the city, famous Osh vineyards flourished, peach orchards rustled, and the renowned world-famous Uzgen rice was cultivated. The only relict nut forest in the world, whose fruits were sold in the Hellenic world under the name "juglans regia" (royal walnut), grew near the city of Osh.

One of the achievements of the economy during the Karakhanid period was the established production of a number of goods. The following industries were developed within the state: winemaking, glass production, metallurgy (furnaces), weapon production, agricultural tools, and various types of ceramics, blacksmithing, coin minting, and processing of agricultural products. The Karakhanids created a number of large structures (for example, the Burana Tower and the Uzgen Minaret).

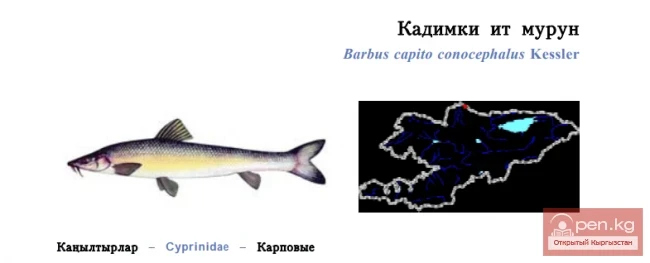

In the economy of the Yenisei Kyrgyz, the leading roles were occupied by animal husbandry, agriculture, mining and processing of ore, hunting, and fishing. Farmers grew wheat, millet, two varieties of barley, and hemp. They used a network of irrigation ditches for crop irrigation and ground grain on hand-operated grinders — zhargylchaks. The population raised horses, camels, cows, and sheep. The wealthy had several thousand heads of livestock in their farms, some of which were kept in enclosures. This was evidenced by numerous archaeological finds of haymaking tools. Residents of mountainous and forested areas domesticated deer, roe deer, and ibex, hunted fur-bearing animals, wild geese, and ducks, and engaged in fishing.

The Yenisei Kyrgyz maintained active trade relations with other peoples through one of the branches of the Great Silk Road, which crossed the lands of the kaganate. This branch, called the Kyrgyz Path, began in the Turfan oasis, went north towards Tuva, along the Yenisei River, and reached the very residence of the state. Merchants bought horses, furs, musk (spices), mammoth tusks and bones, valuable types of wood, silverware, etc.

The strategic direction of the Kyrgyz economy was considered to be the extraction, production, and processing of iron. Therefore, this industry was widespread from the Sayan to the Kuznetsk mountains and even in the Minusinsk basin. Local residents still point out places where "Kyrgyz blacksmiths worked." Analysis of the remnants of fused alloys from furnaces and slags showed that ore was delivered here from distant distances — no less than one hundred kilometers. From the smelted iron, Kyrgyz craftsmen made heavy daggers, battle axes, maces, arrow and spearheads, and horse harness accessories. The most traded and sold goods were various arrowheads. The Kyrgyz supplied them to all of Southern Siberia.

Blacksmiths produced a wide range of household utensils and tools — plows, harrows, axes, sickles, hoes, and various devices for working with wood, iron, and non-ferrous metals. Scholars noted that the blue Turks and other related tribes living nearby learned to smelt metal and produce various tools from the Yenisei Kyrgyz who were their contemporaries.

Among the blacksmiths, coiners and jewelers stood out. Folk artisans created highly artistic products from bronze, silver, and gold — dishes, belt buckles, horse harness, military equipment, weapons, and jewelry. The products featured intricate ornaments or stylized images of animals. The art of ceramics reached great perfection among the Kyrgyz. A type of ceramic ware known as the "Kyrgyz vase" became particularly widespread.

For making clothing, various fabrics, skins, and furs were used. The clothing of the nobility was distinguished by its splendor and expensive decoration. Wealthy Kyrgyz wore white felt hats with high crowns and outwardly turned brims, and outer garments adorned with rich embroidery.