Bais, Biis, and Manaps

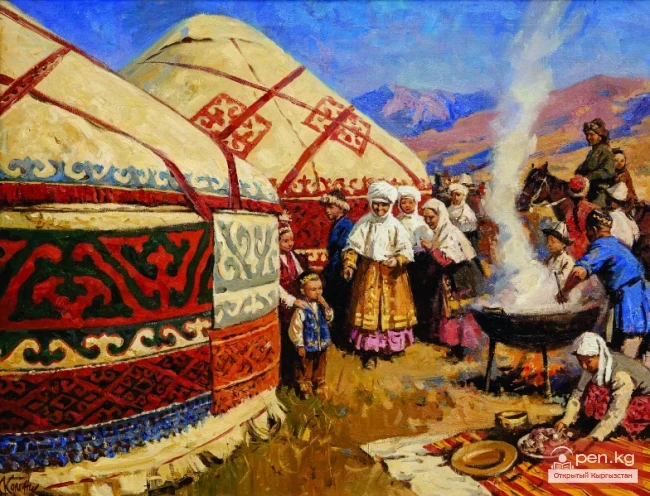

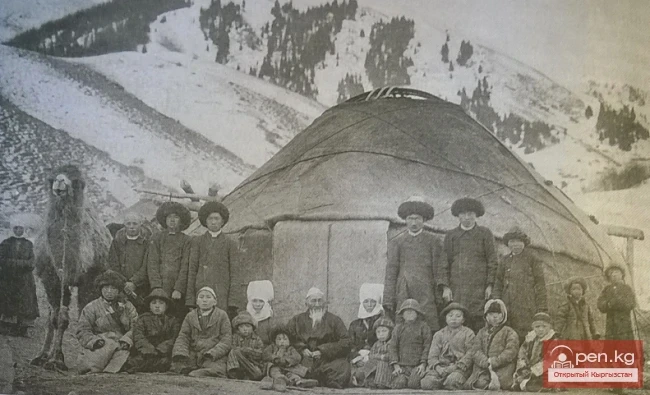

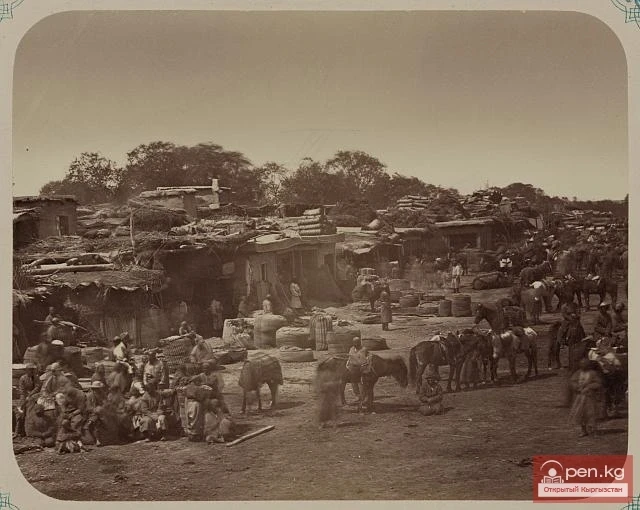

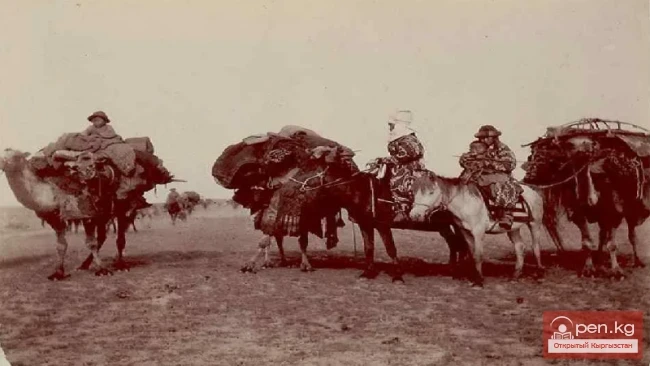

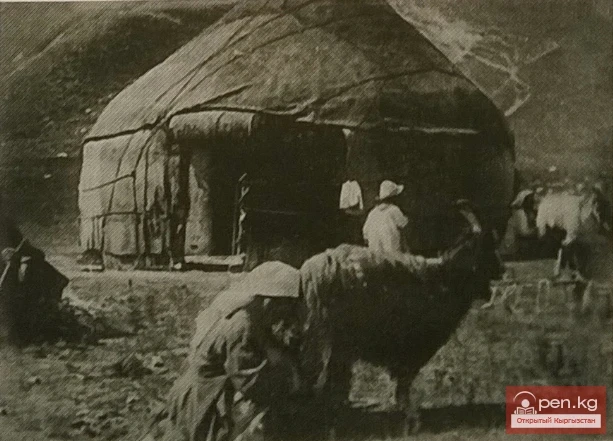

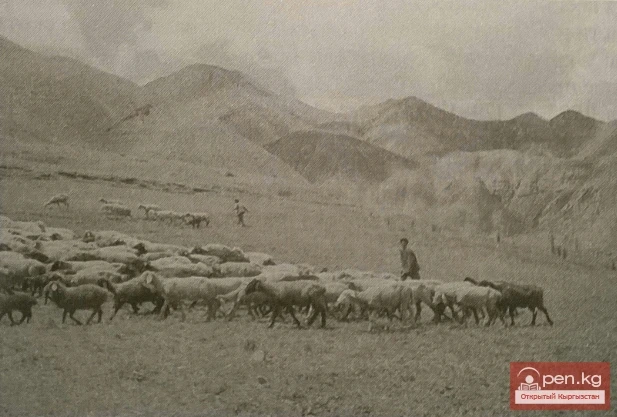

The measure of wealth and the main equivalent in trade and economic relations was livestock; accordingly, the prosperity of a household was determined by its quantity. Bais were categorized based on the composition and size of their herds, as well as their lifestyle and personal qualities: “1) chon bai - big bai or mart bai - generous (a wealthy person who was not stingy and was acquainted with the powerful); 2) saran bai or koltukchu bai - stingy bai (lived poorly, avoided guests); 3) sasyk bai or kokuy bai - smelly bai, a miser; 4) jeke merez bai - reclusive bai (lived separately, only moved with his family); 5) uyutkuluu or kordoluu bai - hereditary, ancestral bai; 6) ordoluu bai - bai close to the ruler’s court” (KRS. 1985. p. 94). B. Soltonoev classified bais into four categories. Chon bais were considered hereditary, ancestral wealthy individuals, distinguished by aristocratic manners, living in cleanliness, dressing in expensive clothes, and eating well; the wife of a bai and other household members did not perform dirty work. They were served by servants, slaves, and poor and dependent relatives, whom such bais could support with livestock. The other three groups of bais made up a category of wealthy individuals who led a secluded lifestyle and dressed modestly. For them, the preservation and increase of their livestock was paramount, and they did not share it with anyone (Kyrgyz. 1991. pp. 598, 599); there were no significant property differences among them, and they did not enjoy the respect of the people. Representatives of these groups exploited poor relatives under the guise of clan mutual assistance.

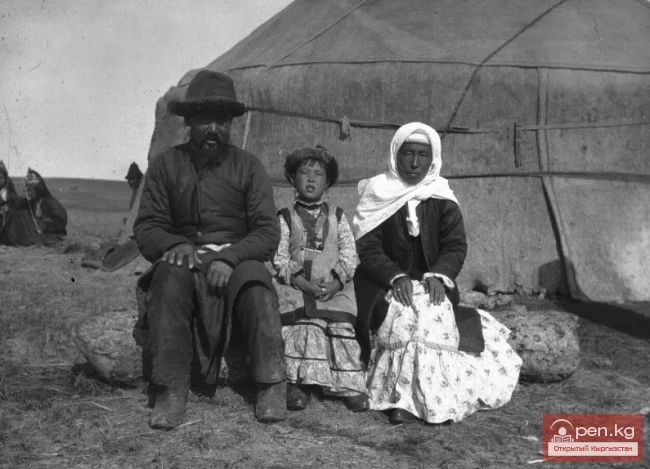

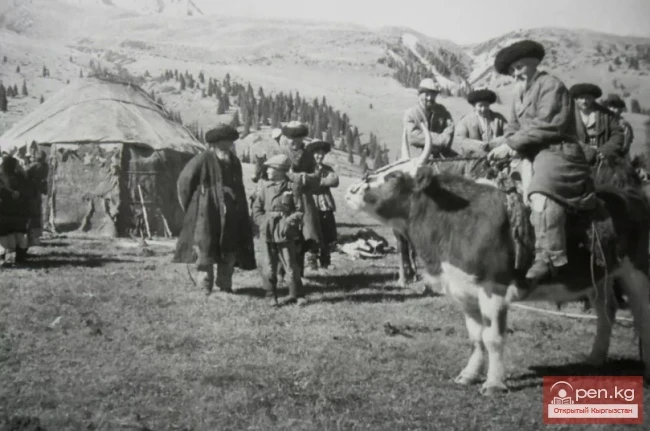

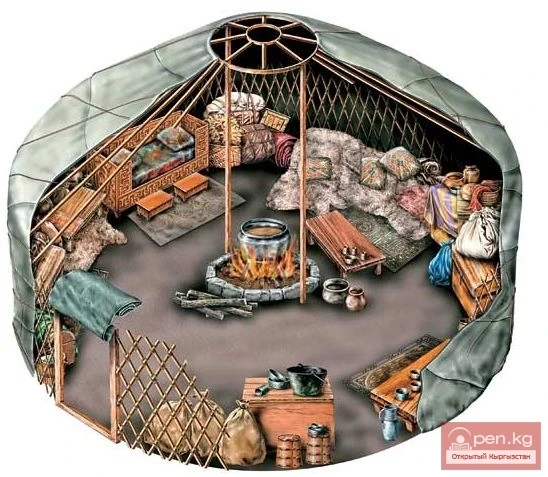

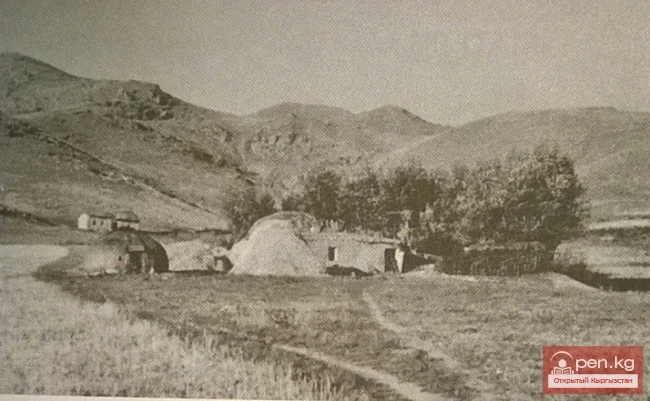

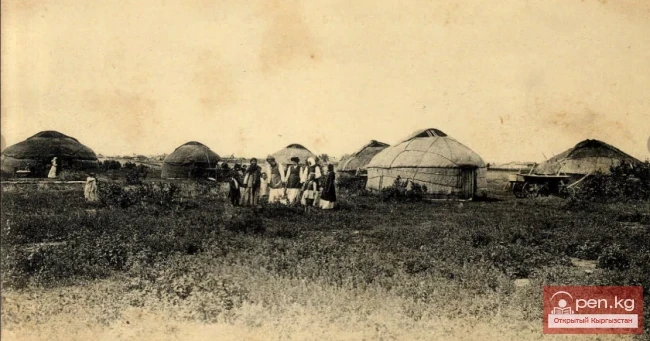

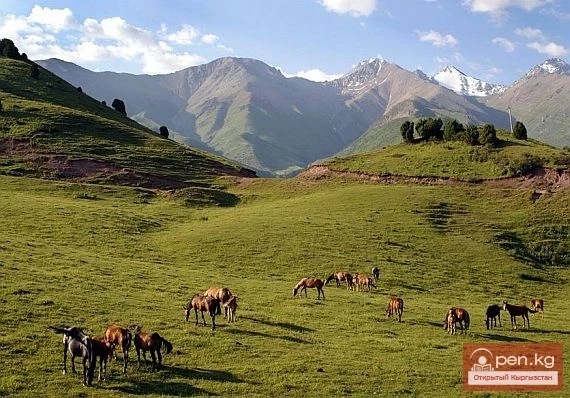

In general, bais, especially chon bai, uyutkuluu bai, ordoluu bai, owned from several hundred to several thousand heads of livestock, including large cattle. They were bearers of elite nomadic culture, active and engaged participants in socio-political processes, and custodians of folk traditions. Customs and rituals of the life cycle were performed most fully in bai families.

High positions in the social hierarchy were held by biis. Initially, the bii likely managed the affairs of the nomadic society. Derivatives of the word “bii” include biilik - power, biyle - to rule. Biis were divided into village and clan (tribal) (Kozhonaliev, 2000. pp. 19-24). S.M. Abramzon believes that biis were the main backbone of the feudal-clan nobility of Kyrgyz society in the 18th century and earlier, concentrating leadership of public life in their hands, including the judiciary - the main function of governance at that time (Abramzon, 1990. p. 168). Later, in the first half of the 19th century, with the emergence and strengthening of the institution of manap, biis only performed judicial functions based on customary law (adat) (Dzhamgerchinov, 1958. p. 98). However, they began to share judicial authority with a new energetic social group - manaps.

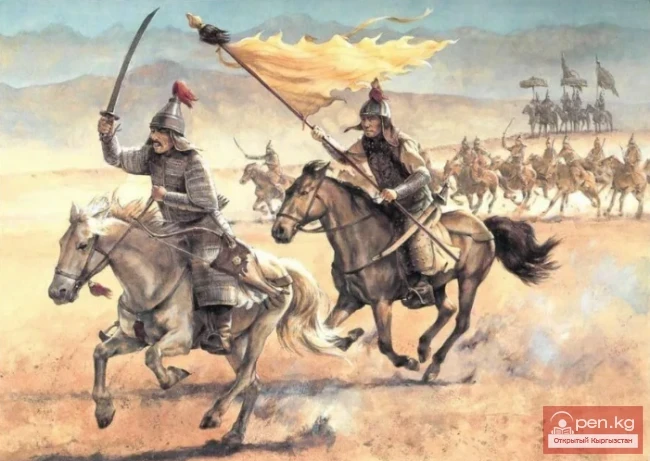

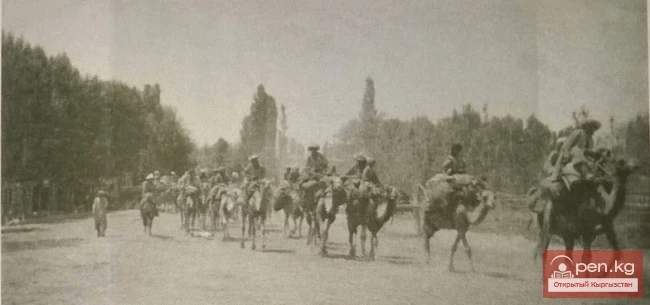

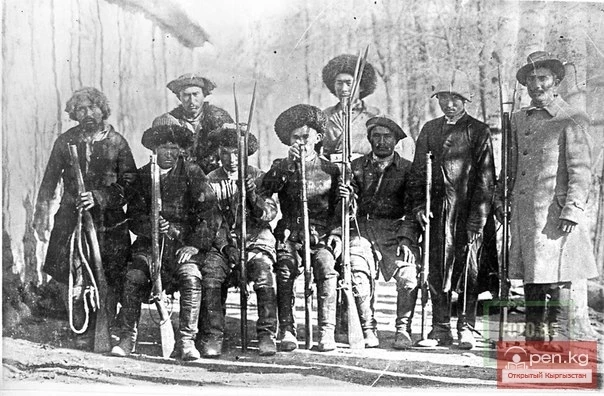

According to historical sources, at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th centuries, some groups of northern Kyrgyz began to have manaps - a new social layer of people, the origin of which is debated. Some historians believe that manap is a new name for the old term bii, and manaps became, just as in ancient times, clan leaders. Others refer to them as a new layer that emerged as leaders without the support of clan elders, i.e., usurping power within the clan. Regardless, a manap was a type of leader of a clan or tribe. By the 19th century, manapship represented a real institution of power, relying on clan solidarity (Dzhumanaliev, 2003). Manapship was more distinctly manifested among the tribes of sarybagysh and solto, less so among the sayaks and bugus, and was completely absent among the Kyrgyz of the South. According to popular beliefs, there were several categories of manaps: 1) chon manap or aga manap - senior manap (to whom smaller manaps of his clan or tribe were subordinate); 2) zhynzhyrlyu manap - hereditary manap; 3) chala manap - secondary manap (dependent on the senior manap); 4) cholok manap - the smallest manap (from such manaps, fifty men were usually chosen during the tsarist period); 5) bukara manap - a relative of the manap who still stood above other people, among them were also completely ruined individuals (KRS. 1985. p. 16). Manaps were in the same social stratum as bais. Unlike the latter, there was a hierarchy within the manap layer: smaller manaps depended on the seniors. Senior manaps had under their command populations of tutun - up to a thousand or more, owned vast herds, and performed authoritative functions, including judicial ones. The status of senior manaps was inherited (Abramzon, 1990. pp. 169, 170). The self-rule bordering on tyranny towards ordinary herders and farmers was almost limitless: “manaps had almost despotic power over their subjects” (Radlov, 1989. p. 353).

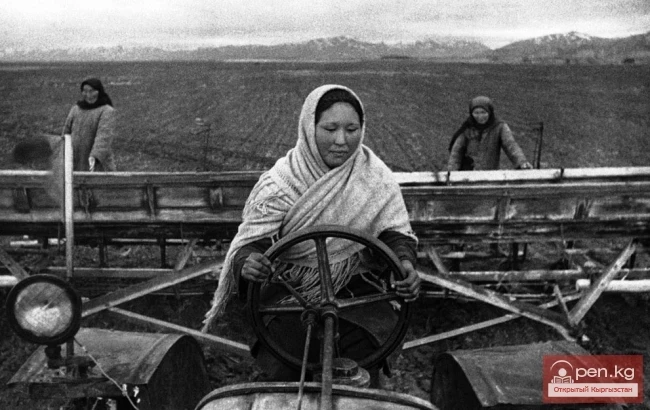

Social and professional structure among the Kyrgyz