Reformers from the Elite Layers of Society

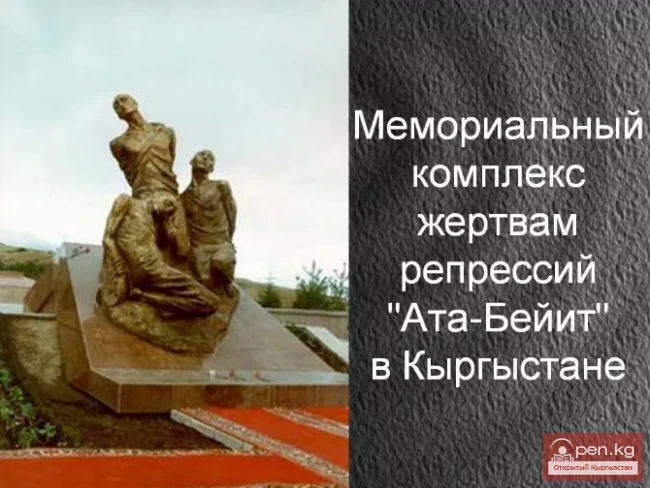

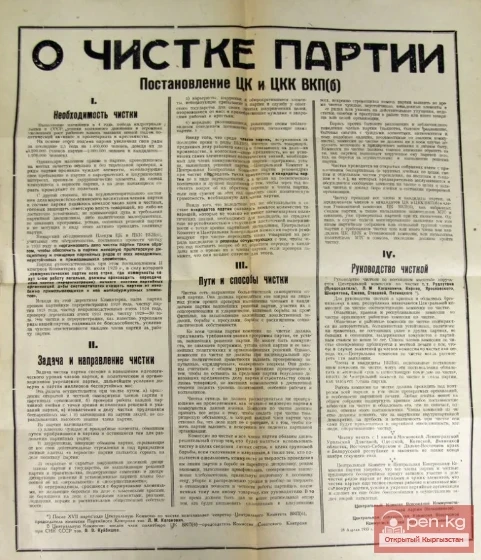

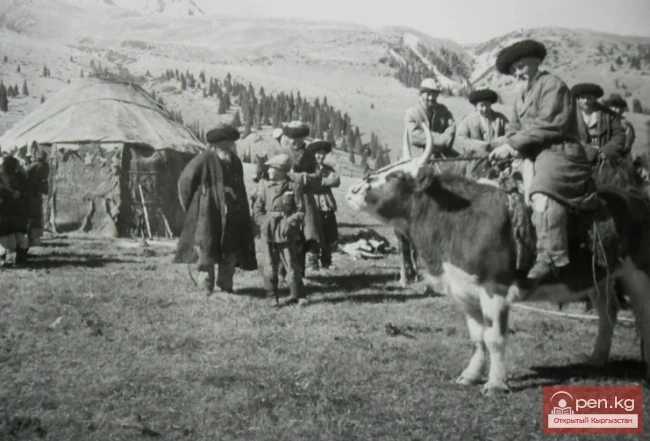

Many Kyrgyz Soviet-party leaders were pursued by the Soviet authorities for their so-called connections with the wealthy and the clan leaders, and some were even convicted, such as the second secretary of the Kirghiz Regional Committee of the Party D. Babakhanov and the chairman of the regional union "Koshchi" R. Khudaikulov. Their "connections" with the so-called "exploiters" had nothing criminal, illegal, or political about them. The newly emerged Bolshevik leaders among the Kyrgyz, having formally adopted the slogans of Bolshevism, continued to live their previous lives, as they knew no other, guided by the customs and traditions established in the clan nomadic society. It was not the ideology of Bolshevism that determined their everyday social behavior, but the norms and ethics of the clan structure. The revolutionary Yu. Abdrakhmanov referred to the contacts of Bolshevik leaders with the clan leaders as "mastering the clan structure."

He called on the European political leadership of Kyrgyzstan to conduct such a policy, which could not grasp the specifics of the social behavior of nomads. Another national politician, A. Sydykov, also urged to adapt the clan structure to the Soviet system, but in a somewhat veiled and more understandable form for Europeans. This referred to implementing personnel policies that took into account not class characteristics, but the level of education and business qualities.

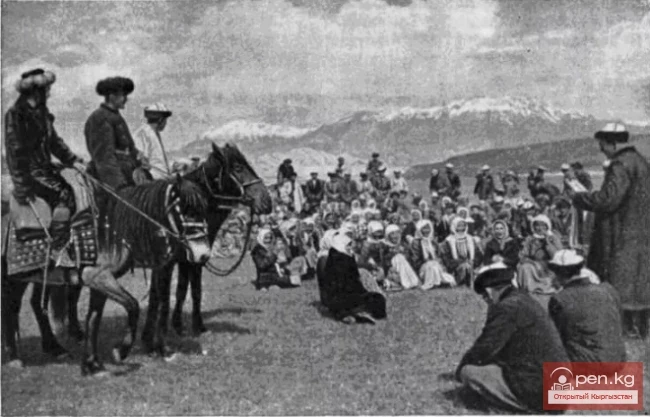

The latter were undoubtedly possessed by representatives of the Kyrgyz clan elite, who were perceived in the public consciousness of the nomadic Kyrgyz masses as true leaders entitled to issue sanctions.

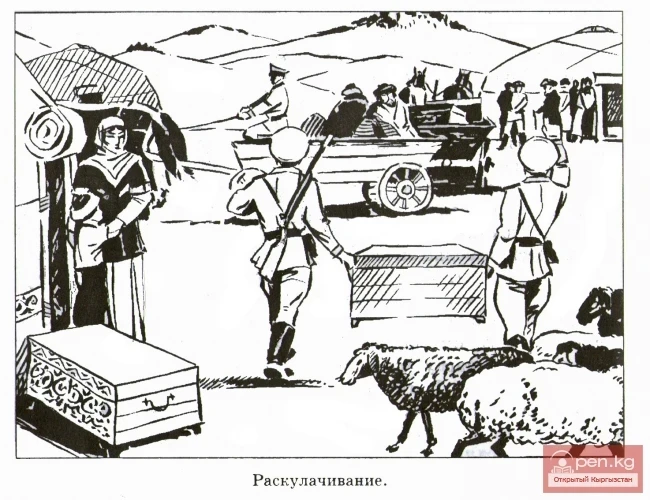

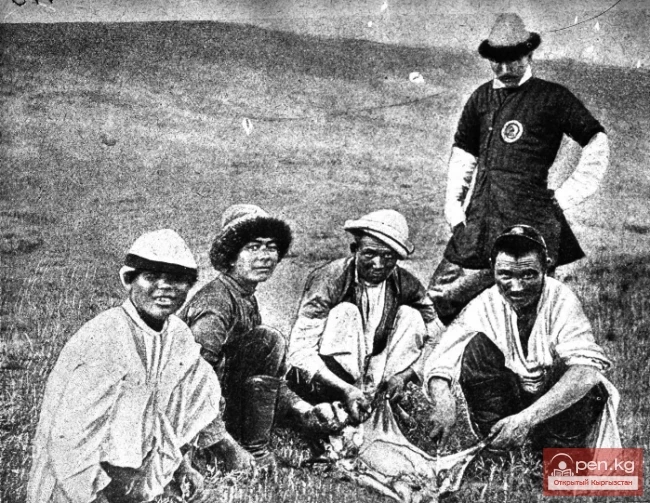

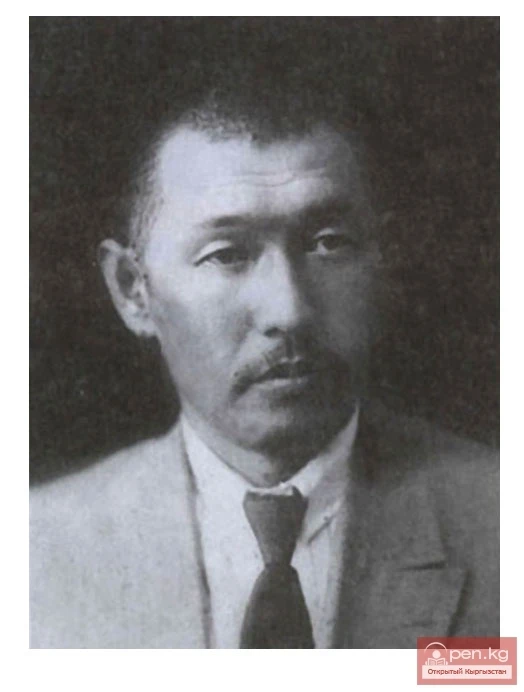

Only they could reform the Kyrgyz clan society, for the ordinary nomadic masses followed them and believed in them, seeing them as subjects of behavior and action. Therefore, the basis for reformism in Kyrgyz clan society could only be representatives of the elite layers of society, which is indeed what happened. With rare exceptions, the Bolshevik elite of Soviet Kyrgyzstan consisted of former clan leaders, wealthy individuals, civil servants, and the old intelligentsia, as well as representatives of the clergy, but not all of them were destined to become true reformers and innovators. Thanks to their education, they stood several orders above their compatriots, the majority of whom conservatively viewed the possibility of replacing the traditional world order with a new, Soviet one.

The novelty and uncertainty frightened the nomadic masses, who believed that any change or violation of the foundations of the surrounding and internal world could lead to nothing good, as they were convinced that any change meant interference in the prerogative of higher powers. Here was precisely the case when the first thought according to the laws of traditional thinking, while the second thought according to the laws of more or less rational consciousness. At the same time, there is no reason to fear that the differences in the type of consciousness of the two groups constituted a serious obstacle to communication and mutual understanding between them, leading to the rejection of each other's thoughts and feelings.

Ordinary nomads and educated representatives of privileged classes did not perceive or feel themselves as being on different levels or worlds, as was the case, for example, between Russian peasants and nobles, the intelligentsia, and even the lower gentry. The alienation between the latter became one of the most significant obstacles to the penetration of progressive ideas and revolutionary ideology into the village. The failure of the "going to the people" movement in the 1870s seems to be a manifestation of this order. The propaganda of the narodniks did not find much resonance among the peasants, most likely for this reason and also because they spoke different languages—in both the literal and figurative sense.

Let us remember that speaking Russian in the high society of imperial Russia was considered a sign of bad manners.

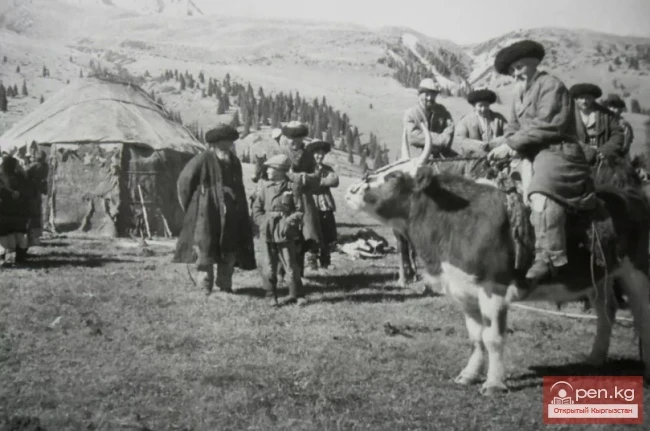

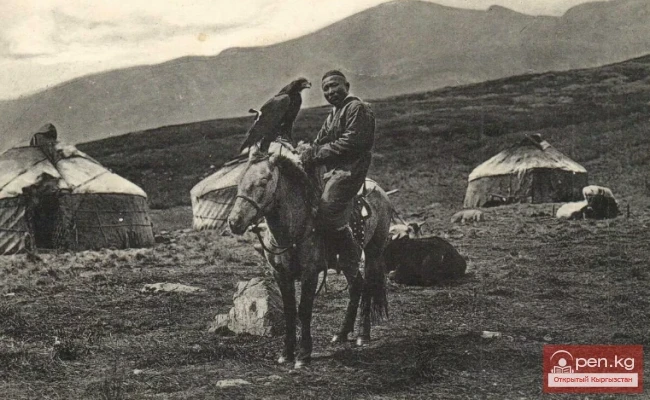

The situation was different in the Kyrgyz clan. The gap between the elite and ordinary members was not so pronounced or almost imperceptible. The Kyrgyz spoke the same language, shared common cultural values, customs, and morals, did not know private property, social inequality, exploitation of man by man, and many other things that K. Marx defined as the mysterious "Asiatic mode of production," which did not fit into his theory of socio-economic formations created based on the study of European experience.

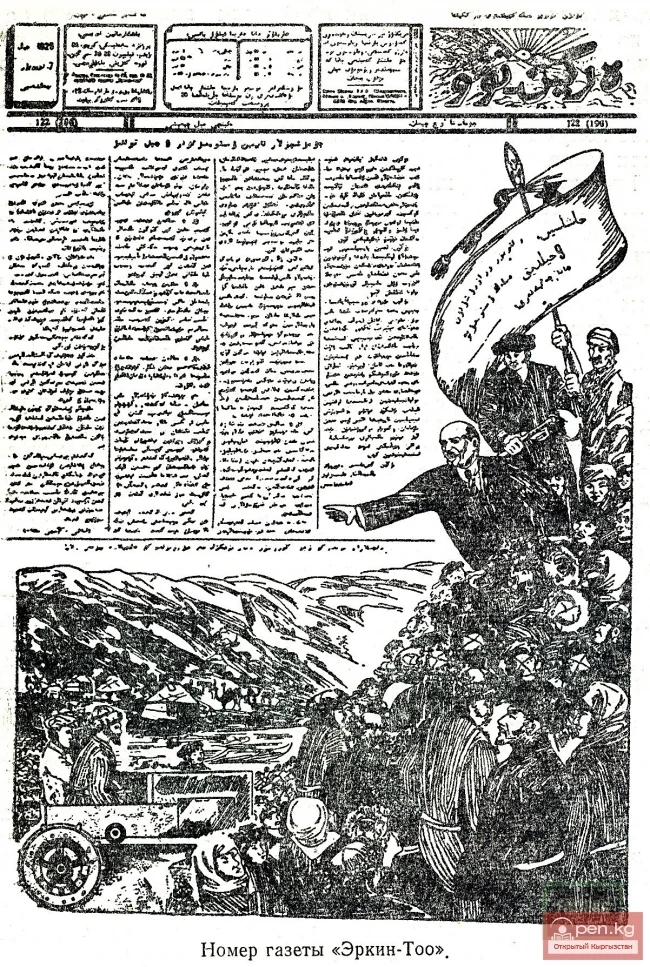

Clan Structure and the Life of Kyrgyz People During Bolshevization