Transformation of Land Use Among the Kyrgyz

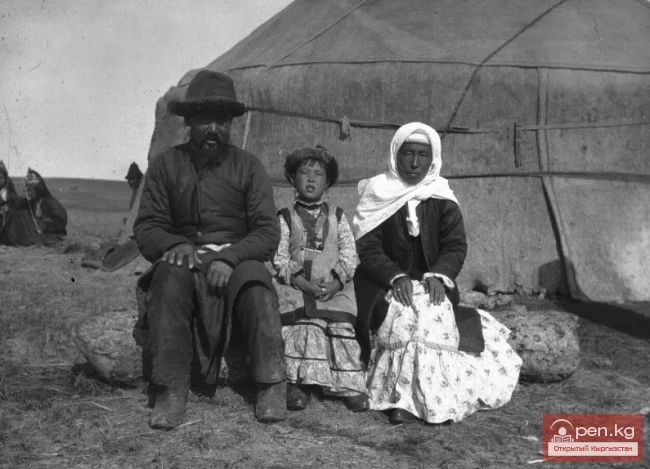

There existed a patronage system that was most vividly manifested in wealthy collectives. Affluent leaders distributed the products of collective labor, expanded networks of social ties, and provided legal protection for their wards. Community heads were consulted for advice and assistance, and they had to find solutions to complex situations. This contributed to the development of a paternalistic psychology. The paradox was that, on one hand, any independent family, being a separate economic unit, adhered to generally accepted norms of customary law and collective obligations, while on the other hand, it could not always protect its private interests, despite the community's liberalism compared to clan-tribal structures. The objectively pressing need for cooperation among herders fostered communal thinking.

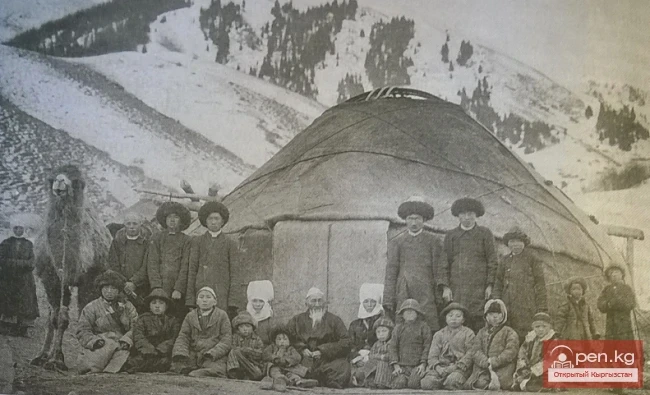

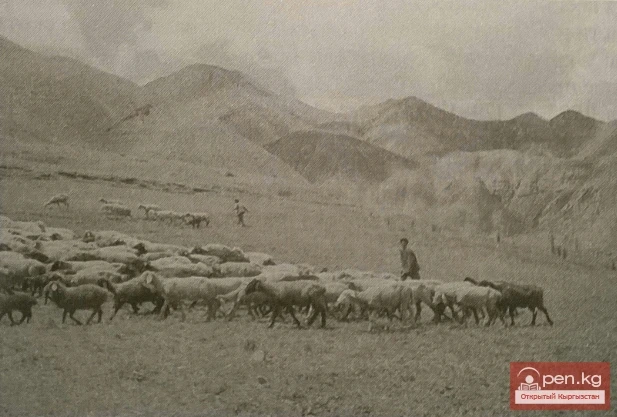

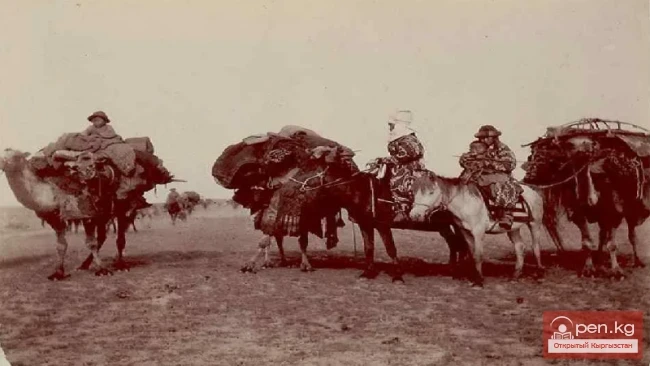

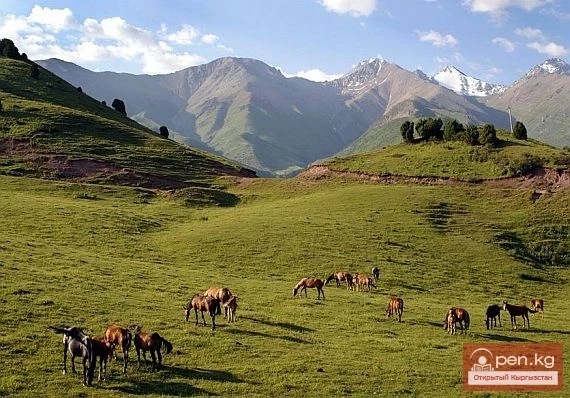

Herders found it inconvenient to concentrate en masse in a limited space due to the specifics of their extensive economy. In normal peacetime, the size of the community was limited by the number of livestock of different types and the pasture resources within which they could graze freely, as well as the landscape. The size and composition of the nomadic collective fluctuated with the seasons: in winter it was minimal, while in the high-altitude summer pastures, where livestock grazed in summer, it was maximal. In narrow ravines, where nomads settled in winter, it was impossible to accommodate large groups, and there was no need for the integration of small communities during this period.

Livestock was grazed at a relatively greater radius from winter encampments. "Each area was occupied by one or two small clans, united into one or two independent economic auls" (Ilyasov, 1963, p. 207).

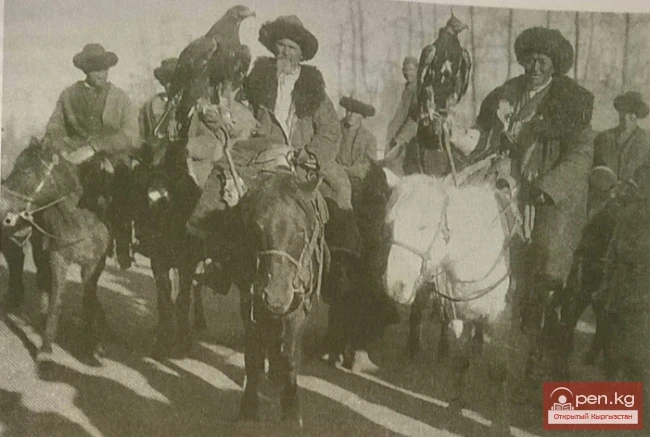

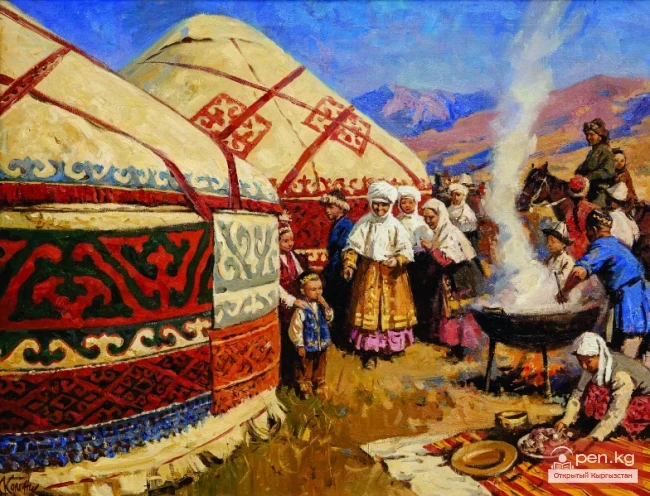

Structurally and numerically, the nomadic community expanded with the onset of warm weather, when weather conditions and the emergence of fresh grass cover allowed for migration to high-altitude alpine pastures. In summer encampments, several minimal communities localized in one area with a small distance from each other. Such settlement and contacts between small communities were dictated not only by economic but also by spiritual needs of the nomads in summer: organizing collective hunts, folk games and entertainment, and mutual feasting (ulush, sherine).

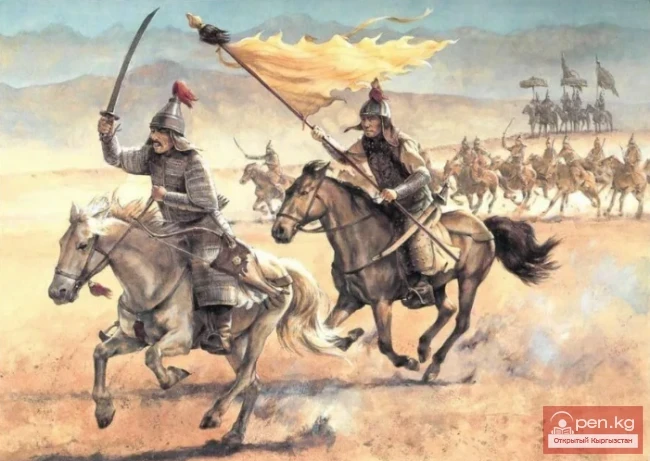

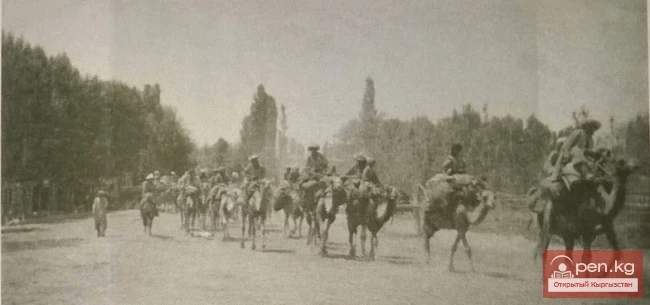

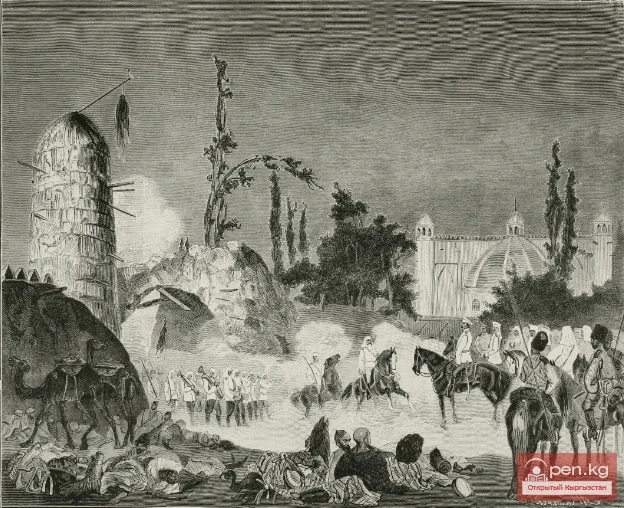

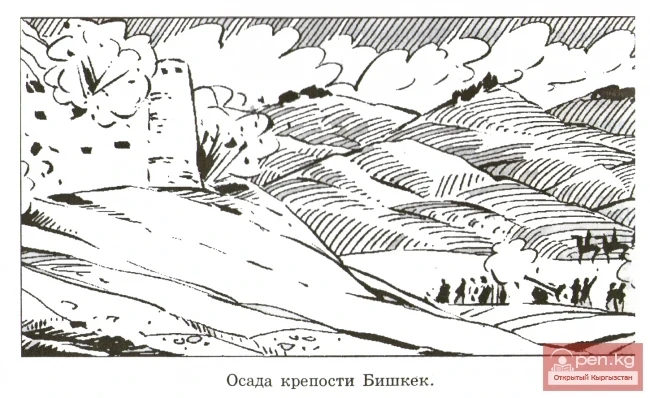

In extreme circumstances, especially during unstable periods of wars and internecine conflicts, the Kyrgyz were forced to concentrate for collective defense against enemy invasions. This led to the transformation of herding communities into military-nomadic units, which were part of a whole clan or tribal union. During such periods, they settled, placing yurts along the river in a continuous chain, as noted by V. V. Radlov. In conditions of political instability and war, communities and clans of varying sizes not only defended themselves but also migrated together. Thus, numerous ails united under the leadership of Umetaly during the process of Kyrgyz territories being annexed to Russia.

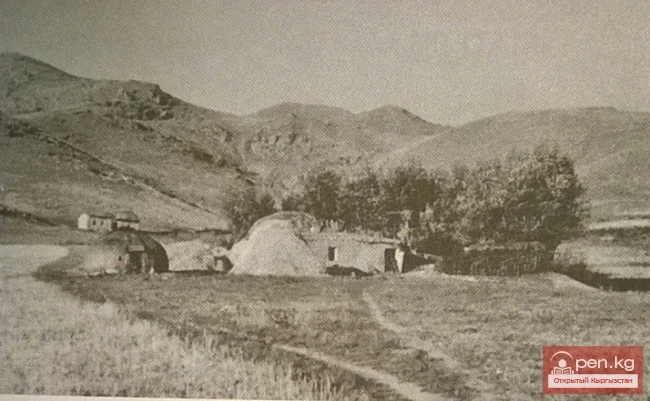

In the second half of the 19th - early 20th centuries, forms of land use transformed. "Clearly, under the influence of some constraints, pasture lands began to be fragmented and secured for smaller groups. The direct seizure of a number of the best winter pastures by the Russians (from the north) and by the Uzbeks (from the south) undoubtedly affected the forms of land use, which became a value carefully protected from both new arrivals and neighboring nomadic groups" (Pogorelsky, Batrakov, 1930, p. 91).

A trend emerged towards the transformation of suitable winter grazing lands into private property.

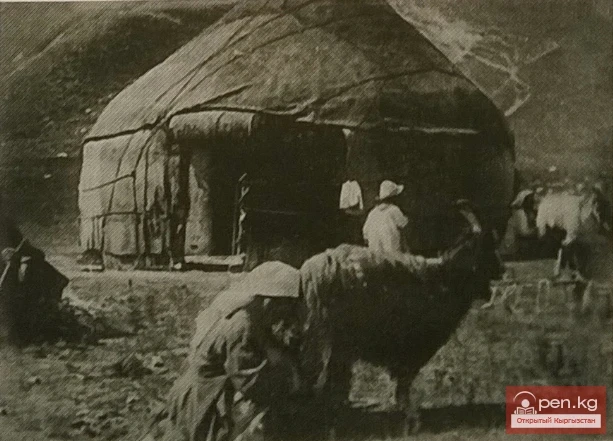

One community, which united several families of close relatives and kin, became an administrative unit at the turn of the 19th-20th centuries. Thus, "the Sarybagysh volost of the Pishpek district consisted of 135 ails, headed by 135 aiyl aksakals. Each ail had from 4 to 15 economic yurts. There were 3,905 men and 1,980 women. All 135 ails made up 16 administrative centers. The Turgenev volost of the Przhevalsk district consisted of 162 ails, managed by 162 aksakals. All 162 settlements were part of administrative ails with a population of 5,963 men and 4,677 women" (Aitbaev, 1962, p. 118). The yurt of the community head was usually located in the center, surrounded by the yurts of other community members.

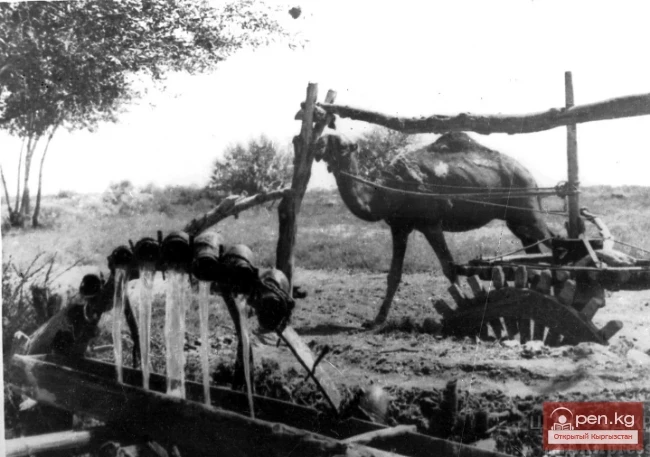

The Russian authorities utilized the traditional social organization of the Kyrgyz: administrative ails, headed by aiyl aksakaldar, served as the grassroots structure for governance and tax collection. The main economic function of the community remained relevant under the establishment of Soviet power. In the first third of the 20th century, for economic reasons, to ensure the protection of pastures, safeguard livestock from attacks and theft, and rationally market livestock, groups of 3 to 21 households often united, most frequently in groups of 6, with livestock numbers ranging from 200 to 1,500 heads (Sydykov, 1992, pp. 111, 112).

During the transition to settled life, the structure of the nomadic community influenced the nature of settlement and the size of settlements. Settling herders sought to consider conditions for grazing livestock in winter. For the construction of winter shelters, they gathered in small groups of 5-10-15 households, while the wealthier households often separated from others. Settlements were created at significant distances from each other. The low population density, the dispersion of buildings, the patronymic nature of settlement, and the presence of "foreigners" in the clan composition were common features of Kyrgyz settlements in the 1920s, whose residents had close economic and social ties, forming a community of settled herders (Sakharov, 1934, p. 104).

In Soviet times, communal traditions continued within villages and neighborhoods. Families living on the same plot were integrated into a neighborly-territorial community, representing a single collective. Close relatives sought to be neighbors. Representatives of other clans could settle nearby. There were economic, spiritual, and other ties among residents. Neighbors formed a common flock of sheep, which they grazed in turn. This practice continues to this day.

The institution of the community has undergone many changes since the collapse of the Soviet Union. This is primarily related to the state's recognition of different forms of property. Active migration movements and the process of globalization also significantly influence these processes. The once strong ties among community members have become weak and episodic due to changing social values and the growing trend of individualization in society.

"Internal Dualism" of the Nomadic Communities of the Kyrgyz