SOCIAL HIERARCHY OF WOMEN

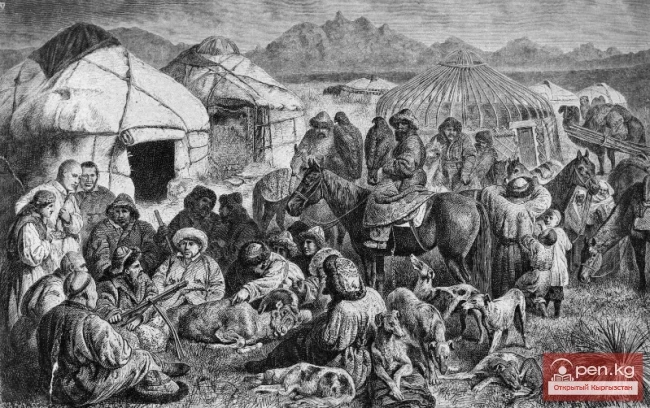

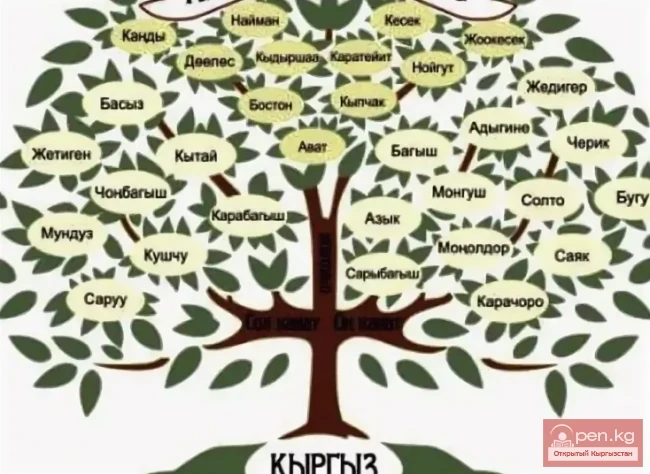

Reliable information about the social structure of the Kyrgyz people can be found in various sources from the second half of the 19th century. During the Soviet period, social relations were viewed from the perspective of class struggle theory. While not denying social and property differentiation, it should be noted that the system of social relations functioned on the basis of patriarchal-clan relationships.

Different strata of society can be grouped according to age-gender, family-marital, property, socio-professional, rank, cultural-symbolic (religious), and mythological characteristics.

Any person, even a slave, was within a system that rejected only those who treacherously violated commonly accepted rules - such people became outcasts. There were very few of them, as leaving the system meant inevitable death. This is a crucial methodological principle that helps to correctly understand the social structure of the Kyrgyz. The formulas “el menen, jurt menen bir bol” (literally, be together with the people), “el korgon kundy kör” (literally, experience what the people experience), “el menen biikisin, elden chykkan kiykisin” (literally, your greatness is with the people, outside the people you are a wild beast) formed the basis of the ideology that ensured intra-ethnic unity, cohesion, and focus on collective actions.

Age-gender hierarchy. People of the same age were collectively called [i]“kurbu-kurdashtar” (literally, peers), “tentushtar” (literally, equals), “dostor” — friends.

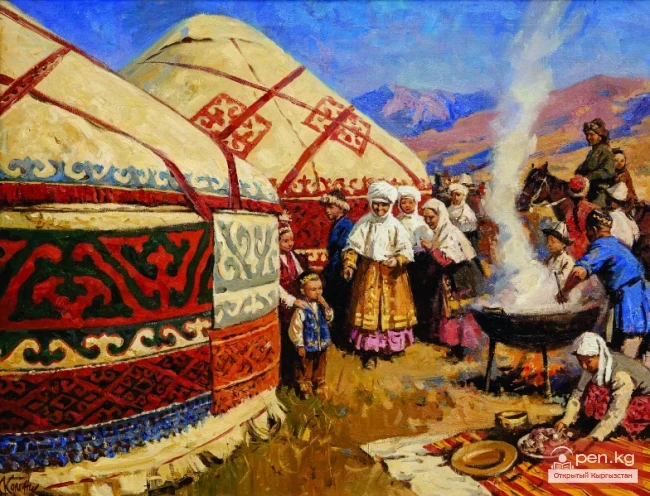

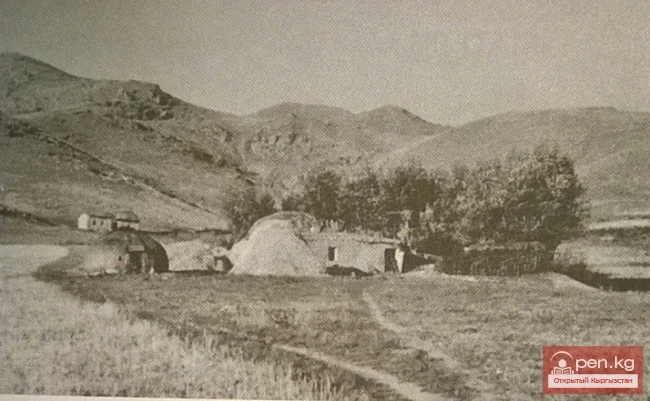

The role of women was to manage the household, raise children, prepare girls for marriage, and participate in inter-family labor cooperation within the family-clan group. A woman's world was limited to her own yurt and village community. The life path of a woman had several stages: childhood - bala chak, adolescence - testier, kyzy kezi or sekelek balagat, engagement period - kayin dalgan kezi, marriage - erge chykkan, mature age - katyn, ayal, old age - baibiche, age of a grandmother - kempir. Before marriage, a girl was in a special position: she was the darling of the family, receiving all the best and beautiful things, and enjoyed universal respect and reverence. She was considered a guest in the house - kyz uydogu konok. She could freely communicate and play with peers, including boys. This carefree period was very short; her position fundamentally changed from the day her father agreed to marry her off. From that moment on, her mother or someone from her sisters-in-law was with her day and night, protecting her chastity in every possible way.

Her sphere of action sharply narrowed, her circle of communication was reduced to her friends, and her main activities were sewing, embroidery, and helping her mother prepare the wedding dowry. Marriage for an engaged woman meant her exclusion from her father's clan. In marriage, a woman's life unfolded within the family, among the family-clan group, but it was not cloistered. The daughter-in-law freely communicated with her peers, could participate in mass public events, including competitions in horseback riding or on foot. With the transition to mature age, her status changed. If a woman became the mother of many children and a grandmother to grandchildren, she enjoyed unquestionable authority not only in her family but also among all members of the family-clan group. Her opinion was respected, and her advice was followed.

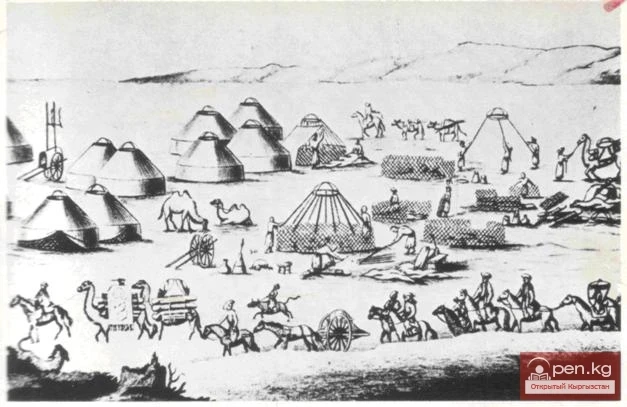

Transformation of Land Use Forms of the Kyrgyz in the Second Half of the 19th - Early 20th Century.