Tribal Institutions of Power

The power system among all groups of Kyrgyz was similar and did not imply centralized governance. It was limited to the tribal level, led by the clan nobility, and governance was primarily based on unwritten adat rules. The relationships of dominance and subordination were built on traditional institutions. In the late 18th - first half of the 19th century, with the inclusion of the peripheral, Pamir-Alai, and Talas Kyrgyz into the orbit of the state policies of the Kokand Khanate and, to some extent, the Bukhara Khanate, a khan's nomenclature began to form, and a new socio-political layer emerged: datka, bek, and others—these were representatives of the clan elite who, alongside performing the duties of biys, also carried out bureaucratic functions assigned by the khan's administration. Among the northern Kyrgyz, a new layer of manaps emerged, not connected to the Kokand Khanate, but becoming an influential force. The people saw in them usurpers of power, tyrants, and destroyers of the accepted norms and rules of the nomadic society.

The tribal institutions of power consisted of a leader, a council of clan rulers, and a military retinue. At the head of the tribe was the supreme biy, chon biy.

The leader of the tribe was inherited; the position was passed from father to one of the capable children, and over time, biys began to be chosen more frequently from among outstanding fellow tribesmen. The biy performed military, administrative, and judicial functions. The military function involved organizing the tribal militia in case of war, appointing commanders of various units, conducting negotiations about war and peace, and mobilizing resources. In all this, the biy relied on the institution of baatyrs. The administrative function included the distribution of pastures among clans, establishing order in the use of water sources, resolving disputes between clan subdivisions within the tribe, punishing flagrant violators of behavioral rules, and convening tribal meetings. In carrying out administrative functions, the biy was assisted by advisors, and the implementation of his directives was carried out by the institution of jigits. One of the important functions of the supreme head of the tribe was judicial. He considered civil and criminal cases—those for which one of the parties was dissatisfied with the decision of the clan biy, or cases of particular significance. Unlike the unilateral judicial proceedings at the clan level, the supreme biy considered cases in the presence of no fewer than three clan biys of his tribe.

Under the supreme biy, there could be a council zhiyin, top, or kenesh, which consisted of clan biys. It was convened when necessary, and each participant had the right to freely express their opinion. The council could work for one or several days, and the expenses for the stay of council members were covered by the supreme biy. Decisions made at the council were subject to strict enforcement; if new circumstances arose, the council was convened again.

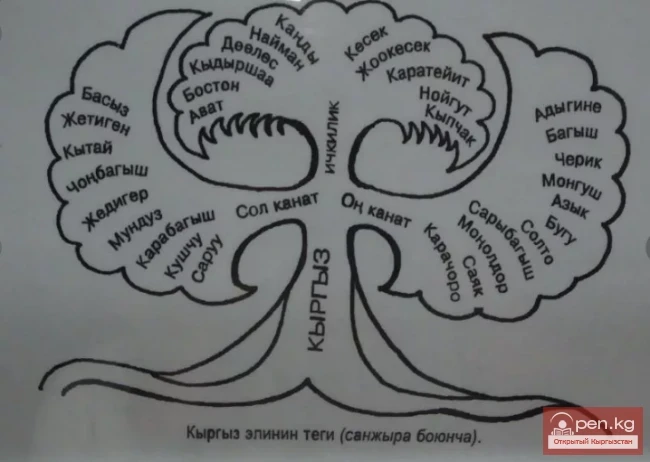

Division of Kyrgyz into Tribes and Clans