Ails among the Kyrgyz

The earliest information about the types of settlements and residential buildings of the Kyrgyz dates back to the second half of the 1st millennium AD. This includes reports from Chinese sources about the Yenisei Kyrgyz: "The Ajo (ruler - A.K.) resides at the Black Mountains. His camp is surrounded by palisades. The house consists of a tent covered with felt and is called Midichzy. The leaders live in small tents"; "In winter, they live in houses covered with tree bark" (Bichurin, 1950. P. 352, 353). Archaeological finds on the Uybat River, dating from the era of the Kyrgyz "great power" of the 9th-10th centuries, document the remains of a clay structure identified as a "castle-palace" of the Kyrgyz khan. Traces of settlement are noted around the "castle." Some of the discovered fortifications also date back to this period (Steppes of Eurasia... 1981. P. 57). Apparently, the ruling elite of Kyrgyz society lived in stationary-type settlements, while the majority of the population resided in temporary settlements (depending on the economic season). This is supported by the Chinese work "Yuan-Shi," which contains information about the Kyrgyz of the 13th century: "The jiliczi (Kyrgyz-AL) live in huts and yurts" (Kychanov, 2004. P. 280).

The modern ethnic territory of the Kyrgyz in the Middle Ages was part of a zone of intensive development of settled settlements, including cities, the number of which was in the dozens. The settled population spoke different languages and belonged to various confessions. The main part consisted of Sogdian trading and artisan classes, as well as the Turkic elite, who concentrated military-political power in their hands.

Representatives of the ruling circles lived in a citadel located in the central part of the city, and according to sources, in yurts. Thus, in the capital of the Karakhanid state in Balasagun (Chuy Valley), khans received guests and foreign envoys in a khan's yurt set up inside the fortress (Reshat Gench, 2004. P. 149-153). This emphasized the prestige of nomadic culture and demonstrated the elite's loyalty to nomadic traditions.

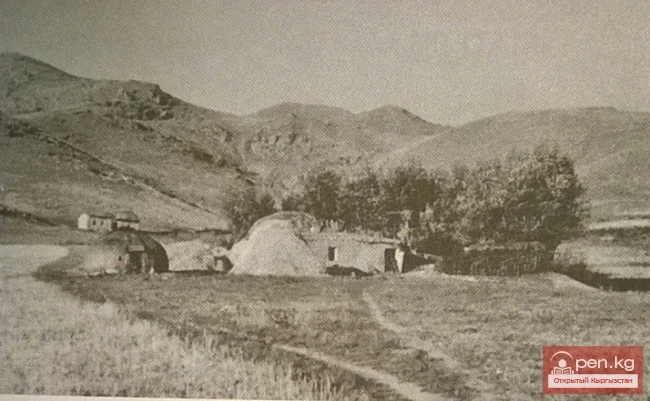

With the onset of the Mongol conquests of Central Asia in the early 13th century, urban life in the territory inhabited by the Kyrgyz declined. The entire settlement system of the Kyrgyz was adapted to a nomadic lifestyle for rapid mobilization in case of danger. V. V. Radlov captured the peculiarity of Kyrgyz settlements depending on the military-political situation. In 1862, he noted: "The Black Kyrgyz live not in auls but in entire clans, in winter placing their yurts along the banks of rivers in an unbroken chain stretching for twenty versts or more. In summer, they move their yurts similarly higher and higher into the mountains, so that each clan grazes its herds on a separate mountain slope. This mode of migration is determined partly by natural conditions and partly by the very warlike character of the people. Such a layout of yurts allows the Black Kyrgyz to bring an army to full combat readiness within a few hours" (Radlov, 1989. P. 348). In 1864, he visited the Kyrgyz of the Solto tribe for the second time, leaving a note: "... the Black Kyrgyz began to change the arrangement of their yurts and started to divide into auls..." (Radlov, 1989. P. 348). This arrangement of migrations became possible after the Solto accepted Russian citizenship, i.e., after the onset of political stability. G. S. Zagryazsky reported that until the mid-19th century, "the Kyrgyz always stood in large auls, with yurts numbering 200 or more" (Zagryazsky, 1874).

Thus, in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the main settlement unit was the ail (konush, zhurt), a settlement of nomadic and semi-nomadic type. Ails mainly consisted of related families, family-related groups, and were named after the head of the group. Their locations were determined by nomadic routes. There were cases when, due to quarrels, grievances, or enmity, a group of families from another family-related group or clan would migrate to an ail by prior agreement. Usually, relatives tried to bring them back (RF HAH KR. Inv. No. 342. P. 33), but sometimes the breakaway families decided not to return and eventually integrated into the structure of the kinship ties of the accepting group.

The arrangement of yurts in ails depended on the terrain. On flat surfaces, yurts were set up in one or two lines or in a circle, with the yurts of the group head, his brothers, and married sons located in the center. The distance between yurts depended on the degree of cooperation in economic activities; sometimes they were placed at a considerable distance from each other. In the mountains, yurts were located along rivers, springs, and in sheltered hollows protected from the winds.

Settlement of the Kyrgyz from the late 18th to the early 20th century.