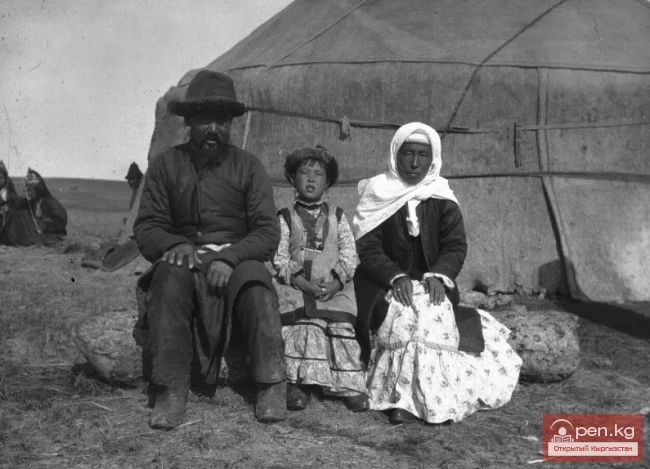

Poor Kyrgyz in the Second Half of the 19th Century

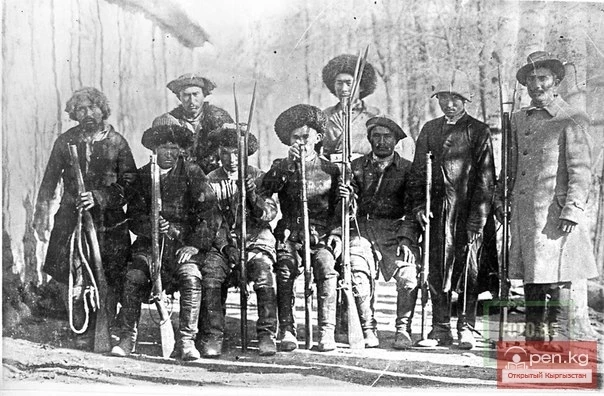

A numerous social category consisted of the poor - kedeiler - ordinary nomads and farmers. During military actions, they formed the backbone of the khan's armies, while in peacetime, kedeiler were the support of the tribal elite. In the 18th and the first half of the 19th century, the poor were generally economically viable, providing for themselves all that was necessary. In case of war, they had at least two battle horses and armor at their disposal. "All able-bodied men of the clan had to take up arms at the first call of the manap to repel an attack or to make one" (Radlov, 1989, p. 353). Refusal or citing the absence of a battle horse meant inevitable death. In every Kyrgyz yurt, there was combat weaponry: spear, axe, sabre, and others, ready for use to repel a sudden enemy attack.

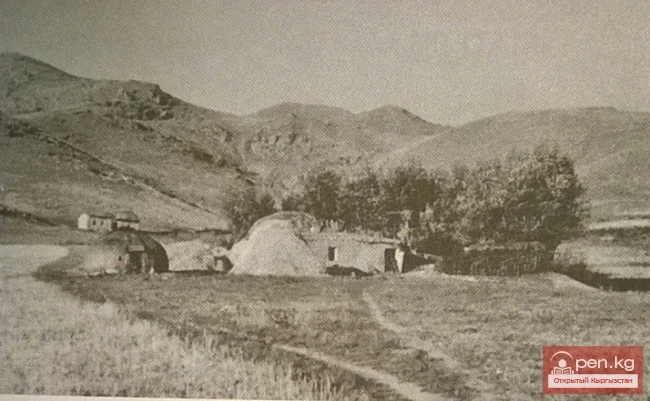

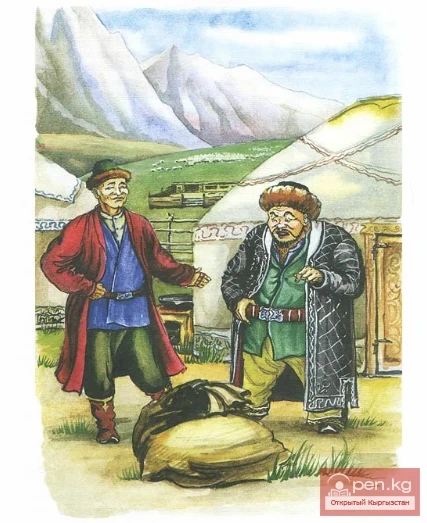

In the second half of the 19th century, the number of the poor increased significantly. For the first time, a category of landless families emerged, which signified the beginning of a serious social crisis. "The number of poor households, deprived of their livestock, grew, becoming completely dependent on the manaps and bai, and forced to serve their farms under labor conditions" (Abramzon, 1990, p. 170). It was during this period that the social term "bukara" emerged, indicating a dependent status from the bais and manaps.

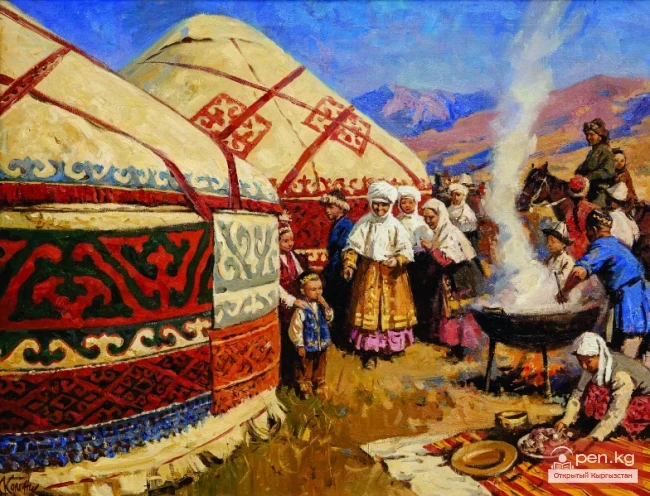

Under favorable circumstances, individuals from the poor could rise to wealth - as a result of successful raids - karymta, winning prizes in competitions, or receiving livestock from wealthy relatives for some merits. The composition of the poor, both herders and farmers, varied, but a common feature was that, entering into a clan subdivision, both groups managed their households together with their wealthy relatives: they migrated with them or worked their lands under labor conditions or shared arrangements.

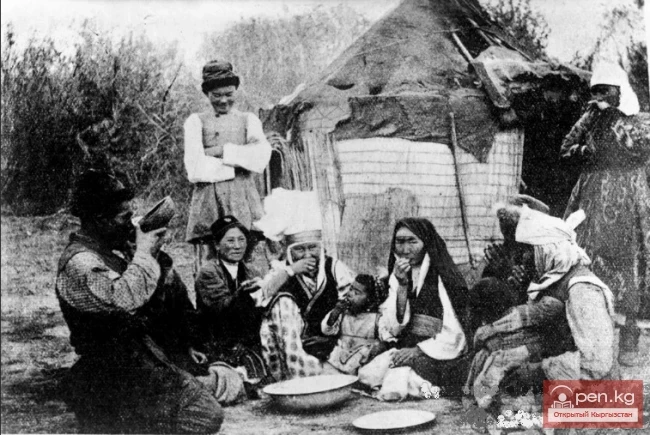

B. Soltonoev provides a folk classification of the poor: 1) tomoyak or orochu; 2) kara kashka kedei; 3) malay or zhalchy; 4) zhylkychy; 5) konshu-kolonchu; 6) zhakyr kedei; 7) ashtykchy; 8) koychu (Kyrgyz, 1991, p. 599). The first group consisted of beggars in all respects. They survived on alms for guarding the property of the wealthy, especially grain pits - oroo, hence their second name "orochu". The second group could have one emaciated horse or cow. Wealthy families avoided such poor people, as they, among other things, had a proud character. The third group consisted of hired workers in wealthy households, gathering firewood, bringing water, and performing domestic work in the homes of the wealthy. The fourth group included horse herders, also hired workers, whose task was to guard the horses of wealthy families in pastures. This was an exclusively male profession, and the work of horse herders was more prestigious and honorable than other occupations of the poor. From among them, crews for raids were formed under the leaders of clans or tribes, as well as cavalry. Horse herders were usually recruited from their own relatives, as those from foreign clans were not trusted. They also served as mentors for the wealthy offspring, teaching them the secrets of horse breeding. In short, horse herding was a unique school of male upbringing. The fifth group hired themselves as a family in wealthy households. Women milked cows and mares, performed domestic work; men took care of the livestock. The children of such families helped their parents. The sixth group represented a completely degraded part of the poor, who had no family or children. Even without trying to work, they survived on random alms. The seventh group of the poor worked the lands belonging to wealthy households, constantly living in winter pastures. The eighth, numerous group consisted of koychu - shepherds, who took care of the small livestock of the bais, and with the permission of the latter, they could keep a few of their own sheep in the common herd. Some of the poor - konshu, koychu, zhilkychy migrated along with wealthy households, while others - ashtykchy, orochu remained in winter pastures, taking care of the wealthy's crops, guarding grain pits, and winter encampments.

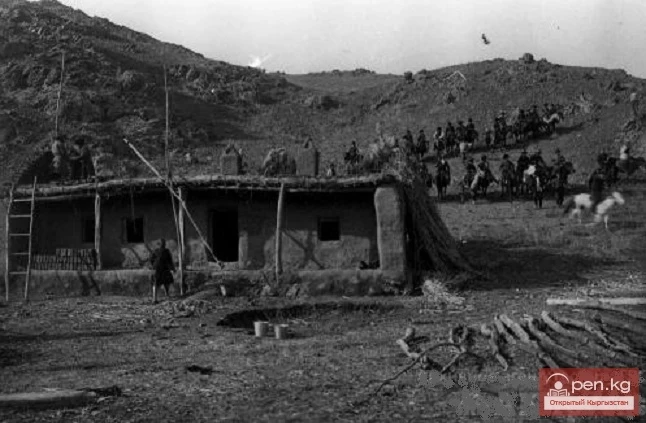

Kyrgyz Elite during the Rule of the Kokand Khanate