In the past, the Kyrgyz produced two types of weapons — cold and firearms, and they made bulletproof clothing. This was necessitated by inter-feudal wars and frequent clan conflicts. They skillfully utilized natural defensive conditions (the surrounding mountains) and constructed special fortifications.

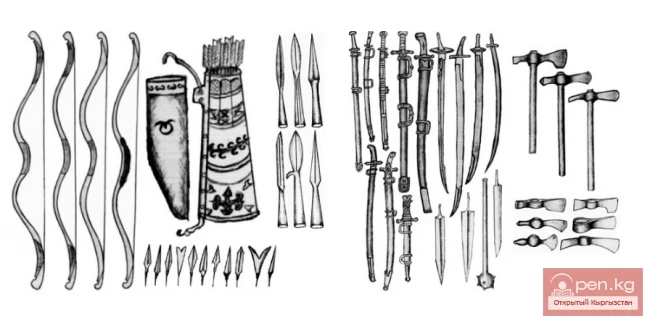

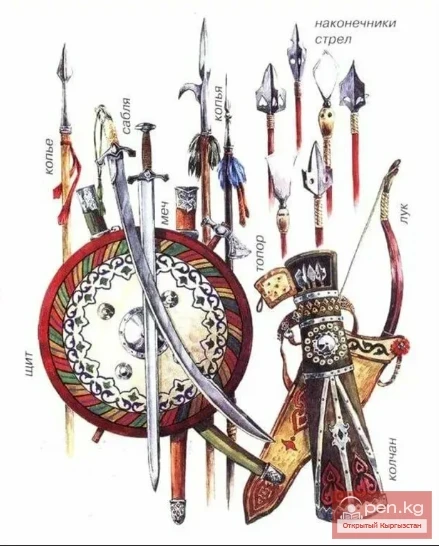

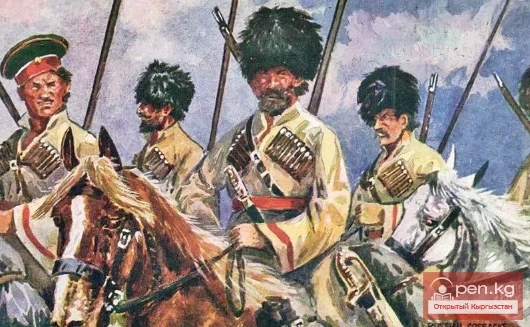

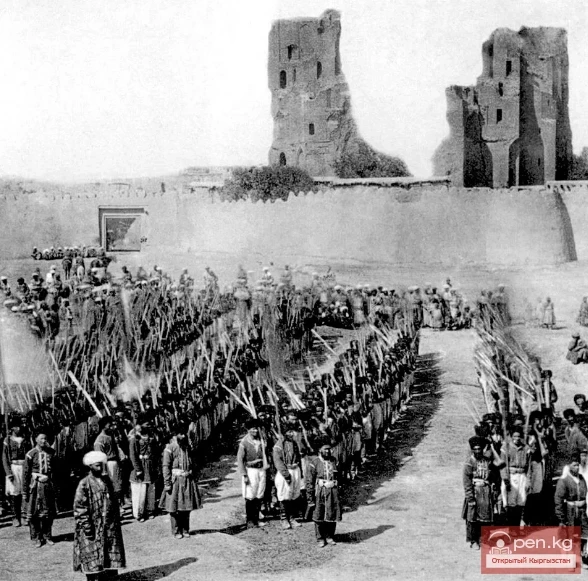

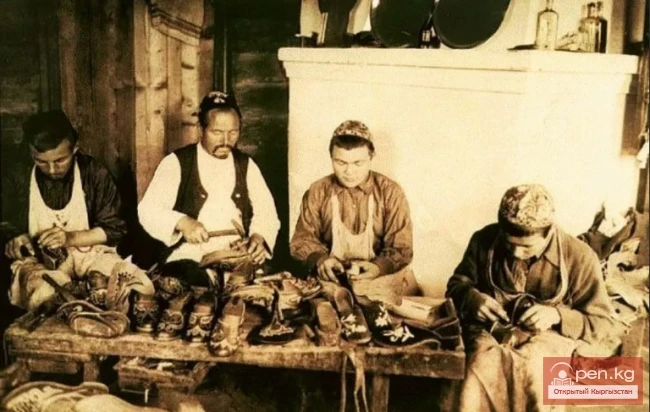

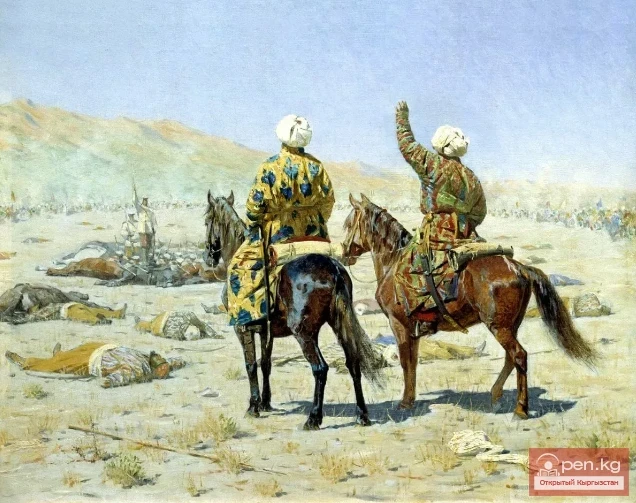

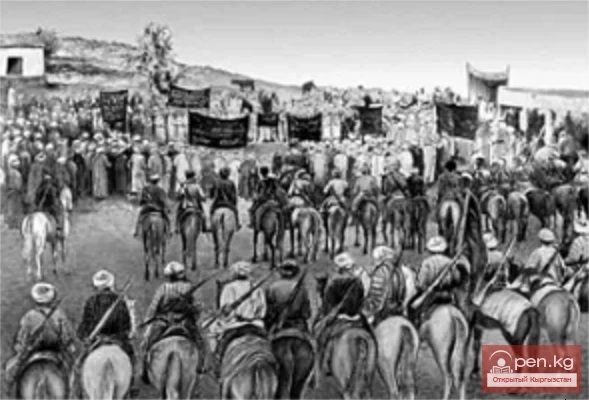

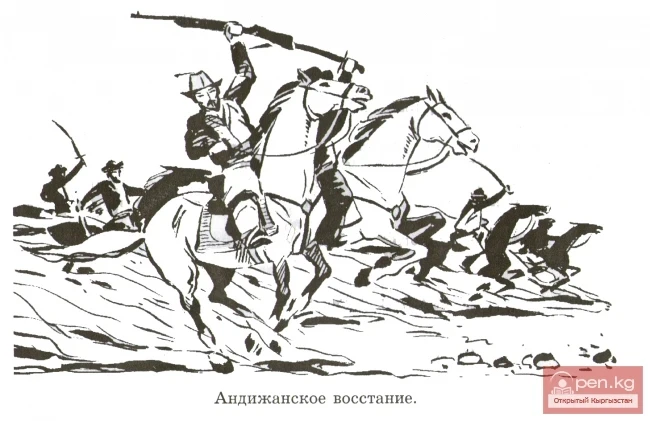

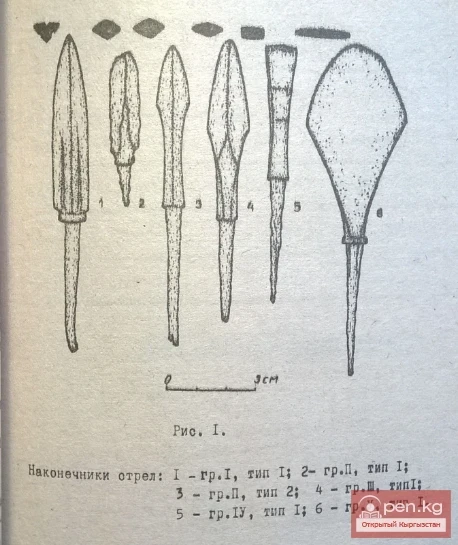

Throughout their long history, the Kyrgyz people have repeatedly had to fight against foreign invaders for national independence and freedom. For instance, in the 17th and the first half of the 18th century, the Kyrgyz fought against Dzungar feudal lords; in the early 19th century, they battled against the colonizing Khans of Kokand. In this struggle, cold and firearms produced by Kyrgyz blacksmiths played a significant role. However, weapons were not only used for warfare but also for hunting, which occupied a considerable place in Kyrgyz life until the mid-19th century. An ethnographer of the last century, N. Zelands, wrote in an essay: “The weapons consist of a spear, a gun, a sabre, and a knife. Additionally, during raids, they used sticks with sharp tips. Knives and tips for sticks are made by themselves in field forges. Bows and arrows have fallen out of use (this information refers to the beginning of the second half of the 19th century — B. D.). To weapons, one can also add the nagayka, the leather part of which is often so thick and hard that a blow to the head can stun.” Close combat weapons intended for defeating an opponent in hand-to-hand combat included spears, swords, sabres, battle axes, palash, maces, daggers, and others. Long-range weapons included bows and arrows, and later (around the 18th century), guns appeared.

In the epic "Semetei," the heroic bow "alenjir zhaa" is mentioned — "destructive, deadly."

Historical sources and archaeological finds indicate that the surfaces of battle axes were sometimes decorated with ornaments made using the technique of inlaying with colored or precious metals, or covered with sheet silver with engraved designs. Such decoration of a battle axe is mentioned in the epic "Semetei": an axe made of white steel with a golden hilt; an axe made from pieces of white steel and decorated with silver and mercury. Gold or silver in powder form was mixed with mercury, which was then evaporated, and the mixture was applied to the item, achieving gilding or silvering.

Currently, ancient types of weapons have almost disappeared among the population. They can only be seen in museums. The largest such repository in Kyrgyzstan is the Republican Historical Museum. Today, one can see the following notable types of cold weapons here:

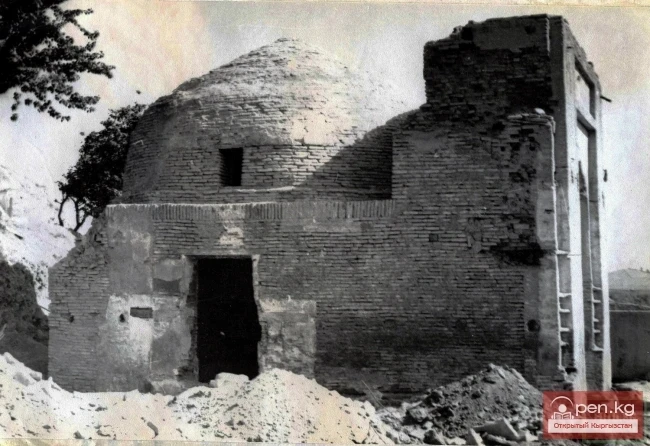

choyup-bash — consists of a stick and a metal knob, which has a through hole for fitting onto the stick. This weapon was used while sitting on horseback, just like a mace. At the site where the former Kokand fortress of Pishpek was located, local historians found a heavy forged mace with a spherical head with spikes. Only a physically strong person could deliver blows with such a mace;

chokmor — a weapon in the form of a stick with a copper ring-shaped sliding knob, having rounded edges. It was used during military confrontations. According to the owner from whom the weapon was acquired, the rider sitting on the horse would put a loop (a strap threaded through a transverse hole at the end of the stick) on his right hand, hiding the knob in his hand. To repel an opponent, the stick was pulled to the side, and the palm, in which the knob was hidden, was opened. The knob would slide down to the end of the stick; this knob was then used to deliver a blow (the stick length is 95 cm, the knob diameter is 13 cm);

shalk-etme — a type of cold weapon. It consisted of a short stick, one end of which was secured with a cast iron knob that had a blind hole. The other end of this stick was attached in a free state to another, longer stick using parallel iron plates. Overall, the weapon resembled a chain.

The ai-balta — a battle axe in the form of a hatchet or halberd with a semicircular blade — was widely used.

One type of offensive weapon of the mounted warrior was the sword (kylch). This weapon was available to the privileged class, professional warriors, heroes, and leaders of troops. Members of the wealthy classes wore them as a "symbol" of honor and power, as well as a sign of glory. Local blacksmiths also produced swords, sabres, and daggers.

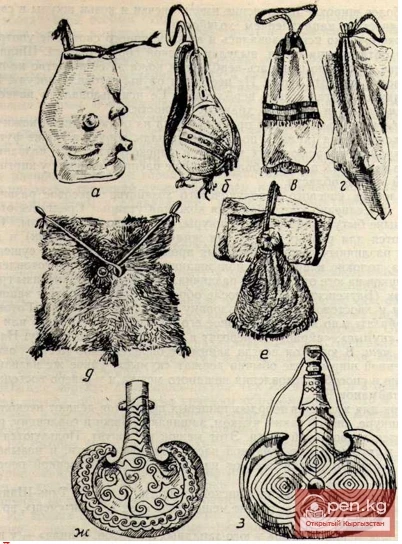

Among firearms, the most experienced Kyrgyz masters made matchlock guns — myltik. They made bullets themselves or cast them from lead purchased at the market. According to legend, one hunter from Aktuz discovered a lead vein in the mountains and gradually began to develop it, casting shot and bullets. This raised suspicion, and he was put under surveillance, and... the vein was revealed. Indirect evidence, along with findings by geologists of ancient workings in Aktuz, proves that lead extraction and the production of shot and bullets were known to the Kyrgyz even in ancient times.

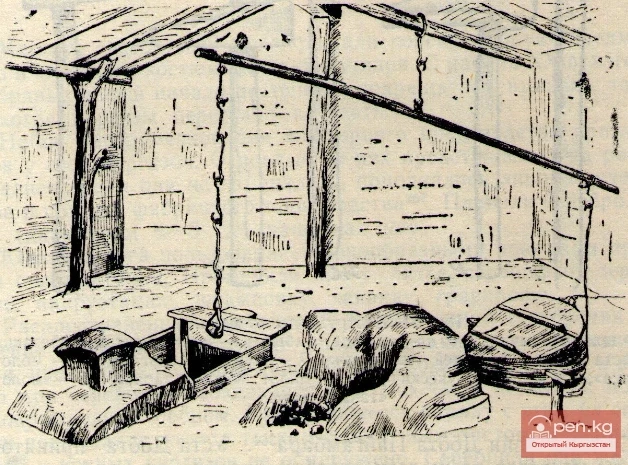

Bullets were cast using bullet molds made in the form of two small blocks of soft stone (the mold for casting bullets, dated by specialists to the 17th-18th centuries, found at the site of the Belovodskaya fortress, was made of brick, which had apparently been fired as early as the 10th-14th centuries). On the surface of both blocks, hemispherical depressions were carved. From these depressions, matching grooves were made towards the edges of the blocks. To prevent the blocks from separating, they were tied together with a strap. The melted lead flowed along the grooves into the spherical depression, where it solidified. Then the blocks were separated, and the round bullet was removed from the depression.