Hunting Tools and Weapons.

Since ancient times, the Kyrgyz have used both "active" and "passive" forms of hunting. The former involves searching for, pursuing, and capturing game by an armed hunter, as well as group hunting. The latter involves capturing animals using pre-set traps.

One of the early forms of "passive" hunting was the use of pit traps (or) with vertical walls. Typically, a camouflaged pit was made, over 2 meters deep and 1.5-2 meters in diameter, to catch wild animals. These pits were dug along paths frequently used by large game. This method of hunting apparently developed from an ancient practice where people would surround and push wild animals off cliffs and ravines.

In ancient times, hunters widely used various snares, loops (tuzak), and nets (tor) to capture wild animals. The bow (jaa) also served as a weapon in hunting (Khudyakov, 1980, pp. 69-71). Gradually, the bow was replaced by firearms. However, in the 19th - early 20th centuries, it was still used by novice hunters, primarily for bird hunting (Aitbaev, 1959, p. 84).

Birds were caught using snares made of horsehair. Traps were set in areas where birds frequently appeared, particularly at water sources or salt licks. Hunters did not leave their traps unattended for long, as other predators or dogs could intercept the catch.

With a sturdier snare (tuzak), hunters targeted wolves and foxes. In ancient times, these were made from strong ropes, and later from cables and wires. Typically, several of these snares were set 5-6 meters apart in secluded spots, in bushes, along narrow animal trails. A bait made of meat (jem olumtuk) was placed in the center of the circle formed by the snares.

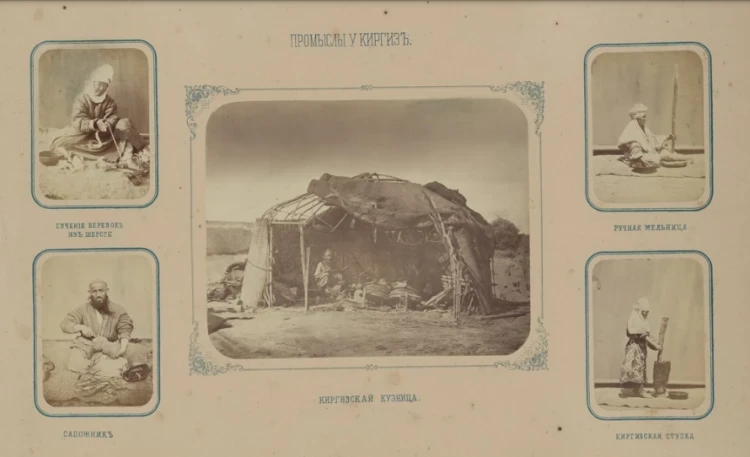

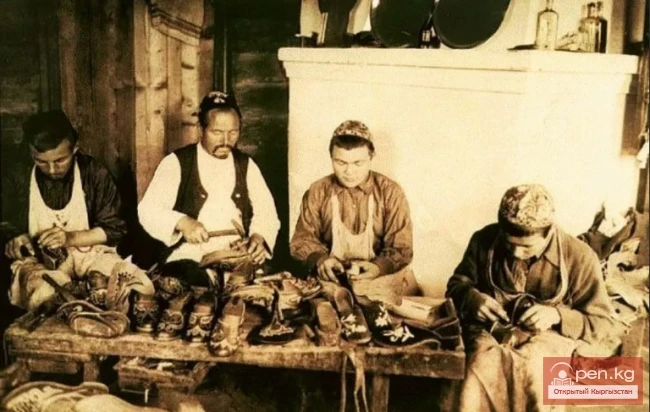

Various types of iron traps for hunting foxes, wolves, tigers, and bears were made by local craftsmen.

Tiger and bear traps were made with teeth on the arms (Aitbaev, 1959, p. 93; Kushelevsky, 1890, p. 304).

Round traps, consisting of two arcs (jaaak), were widely popular. This device was usually set by digging a small pit where the animal passed, with a "ceiling" made to look like an untouched area. One end of the trap was secured with a cable to the ground, in bushes. To catch wild herbivores, traps were set at salt licks where they often came.

The simplest device, the tash trap and kubok for catching animals with valuable fur, particularly for minks (suusar), was a closed structure made of flat stones arranged in a dome shape with an entrance for the animal. Inside, a stone weighing at least 10-15 kg was placed on a stick with bait. When trying to take the bait, the animal would shift the stick and become trapped under the stones, with its fur remaining undamaged and inaccessible to other predators. Another type of trap, the kubok trap, was made of wood. A variant of this device, the asma kubek with bait, was set on tree branches where the minks could climb.

Firearms for hunting became widespread, likely from the 18th century, although they were known in Central Asia at least since the 16th century (da, vidov, 1981, p. 22), or even since the time of the Golden Horde. It was during this time that the southern Altai people used firearms, as evidenced by Russian documents from the 18th century (Potapov, 2001, p. 63). The Kyrgyz, like the Altai people, had long-barreled guns on wooden bipods. Local blacksmiths learned to make hunting guns, either from their primitive forges or by acquiring them from neighboring peoples - Uzbeks, Tajiks, Kazakhs, and Uighurs. The most popular was a simple matchlock gun without rifling, with flint (milteleuu myltik or kara myltik). Starting from the second half of the 19th century, percussion weapons with four grooves - baran - began to be used. Later, hunters acquired berdanks (bardankyo).

Firearms significantly reduced the number of participants in collective hunting.

19th-century travelers described how skillfully the Kyrgyz handled firearms. N. A. Sever tsov recounts a case where a hunter chased a bear and, while galloping, wounded it with a matchlock gun, and then, without stopping, hit the bear again: “... it should also be taken into account that, besides reloading on the run, for each shot, without stopping, it was necessary to strike fire on the match with flint and steel and then insert the lit match into the trigger so that it would hit the powder shelf upon pulling the trigger; all this cumbersome procedure was more difficult at a full gallop than shooting from a percussion gun - yet that same karakyrgyz killed foxes on the run with a single bullet from his matchlock gun, as I later observed” (Sever tsov, 1873, p. 197).

Hunting Techniques and the Division of Game Among the Kyrgyz from Ancient Times to the Early 20th Century.