In folk medicine, compounds of mercury have long been used: sulaim (HgCl2), calomel (Hg2Cl2), lapis (silver nitrate AgNO3) for the treatment of bone and other diseases.

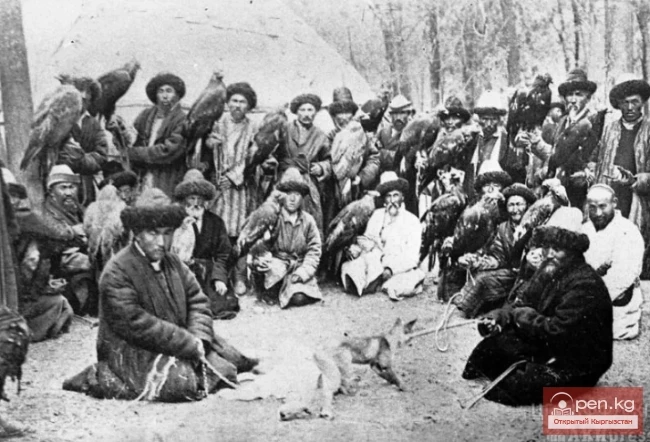

Even with the advent of firearms, the Kyrgyz often continued to use chemically toxic substances for hunting. For example, white arsenic — As2O3 (in Kyrgyz — kuch-ala), which deprived a person of strength, was rolled into a ball or a disk in the shape of a button, wrapped in meat, which was used as bait on the paths frequented by wolves, foxes, and other animals.

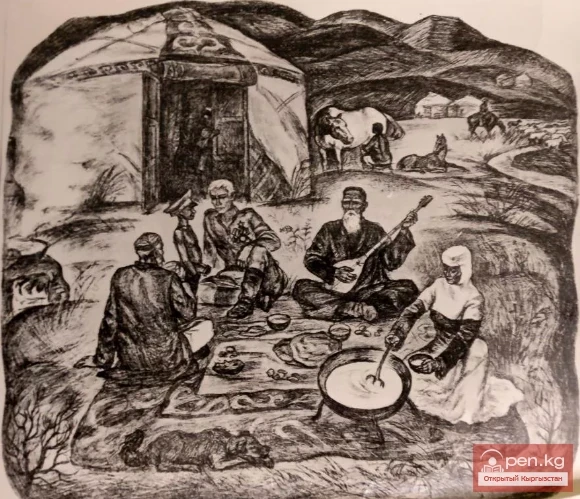

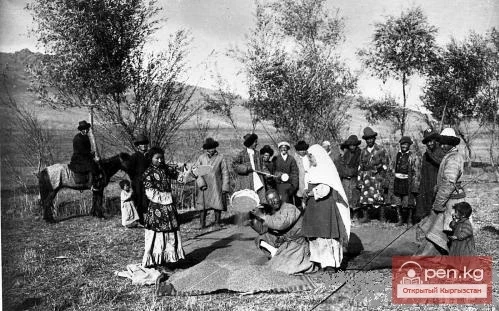

The Kyrgyz, lacking a scientific understanding of chemistry, particularly unaware of the existence of vitamins, empirically linked the usefulness of pasture grasses to their composition, juiciness, and other properties based on their own life experience. They practically confirmed that kumis and ram meat are tastier and healthier for the human body if the livestock is grazed on good grasses (in alpine and subalpine meadows).

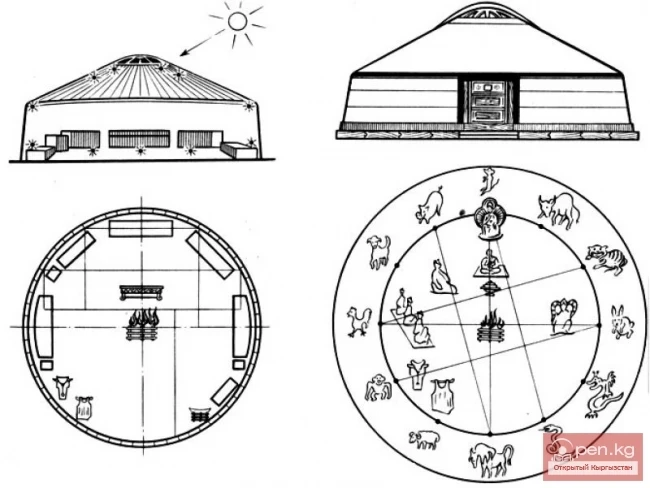

Foreign traders from Muslim states spread Islam among the Kyrgyz along with their goods. To achieve this goal, they did not shy away from any means, often resorting to charlatanism and exploiting the ignorance of the people. For instance, merchants and mullahs from Tashkent and Andijan, when visiting Kyrgyz yurts, discreetly drew a sign with white phosphorus (which they knew how to preserve and carried with them) on the door frame of the yurt. At night, seeing the glowing door frame, people thought that the person who had come during the day was a prophet, and if he appeared again in the village, they dared not refuse him anything. This is how the foreigner took advantage of the situation, deceiving the naive people. Often, such individuals amassed great fortunes by exploiting the Kyrgyz. Not only merchants and mullahs took advantage of the hospitality and trust of the Kyrgyz for selfish purposes, but also various vagabonds (dolu — gypsies, Persians, little people, etc.).

On old graves, a glow is often observed. The explanation for this phenomenon is simple and is as follows. During the decomposition of animal or human remains in the absence of oxygen, phosphorus, which is part of bones and muscles, forms compounds with hydrogen. One of these compounds — liquid phosphine — can accumulate in graves in significant quantities. When it reaches the surface, its vapors ignite instantly. And then a transparent blue flame sometimes rises above the grave to a height of 1 to 1.5 meters. Religious people attributed a mystical character to this natural phenomenon.

To make homemade gunpowder — kara dary (literally, black medicine) — Kyrgyz hunters used kukurt — natural hot sulfur, some types of salt marshes (in Kyrgyz — shor), containing nitrate salts, and archanyn kemuru or kulu — juniper charcoal. The salt marsh was first boiled separately in a certain amount of water, well evaporated, and filtered, then camel hair was added to it and left overnight. A white salt marsh powder settled on the hair, which was removed in the morning. This powder was mixed in a specific proportion with hot sulfur and charcoal, and the mixture was carefully heated in a cauldron until it turned into a thick black mass. The mass was dried and ground in a separate container. This is how gunpowder was obtained.

To start a fire, a Kyrgyz hunter used ottuk — a fire starter. It consisted of three items: dried soft fluffy fiber called kuu — wormwood; a piece of white, very hard stone (natural silicate); and a piece of iron — a striker 1 cm wide and 7-8 cm long, secured to a piece of leather. The stone was held in the left hand, and the iron along with the fiber in the right hand, and a vertical motion struck the stone against the iron. The sparks that appeared upon impact ignited the fiber.

Thus, for everyday needs, people widely used various chemical compounds and substances. The Kyrgyz, of course, did not know the term "chemistry," but through empirical means, by directly passing on their experience and skills from generation to generation, they expanded their knowledge in the field of practical chemistry, which formed their ideas about substances and their effects on the body, etc. The practical need for these compounds and substances in the life of a nomad spurred their reflections and further in-depth study of the surrounding world, seeking ways to enhance the usefulness of natural objects for humans, which ultimately contributed to the formation of a materialistic worldview.

"The historical analysis of the development of chemical knowledge and chemical technology leads to a certain conclusion that the origins and basis of the accumulation of factual material in chemistry were three areas of artisanal chemical technology: high-temperature processes — ceramics, glassmaking, and especially metallurgy; pharmacy and perfumery; the production of dyes and dyeing techniques."

The nomadic Kyrgyz were, to some extent, familiar with all three areas: metallurgy, pharmacy, and dyeing techniques. However, beyond their rudimentary forms, chemical knowledge among the Kyrgyz did not progress due to the limited development of crafts, which was associated with their nomadic lifestyle. Therefore, their knowledge of the properties of substances did not emerge as a separate field, and was far from forming a specific system. They constituted only a part of the practical knowledge of the Kyrgyz, inseparable from specific practical skills, and were passed down together with concrete skills from generation to generation.