The need for measurement and counting arose among the Kyrgyz in the context of their relatively advanced social production and social differentiation. In Kyrgyz culture, several counting systems coexist, which indicates their diverse origins.

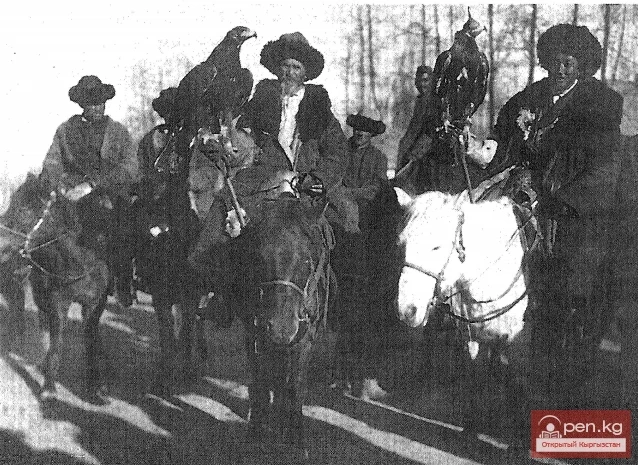

Ancient Kyrgyz used actual mathematical numbers known to the civilized world and could count family members, livestock, arrows in a quiver, animals killed or caught during hunting, birds, etc.

They were familiar with four arithmetic operations: addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. An odd number was called alyk эсеп, while an even number was referred to as tuyuk эсеп. These elementary mathematical skills were necessary for their practical life.

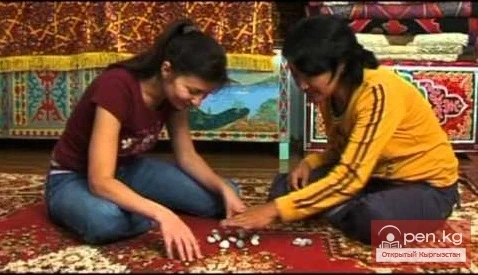

In the national game of ordo (an emotional game among adult Kyrgyz that reproduces a battle for the capture of the khan's camp), and in the children's game of alchik, mathematical operations of addition and multiplication were performed mentally using the concept of birдин учу — five; birдин учу — five alchiks, birдин учу бир — six alchiks, birдин учу эки — seven alchiks, экинин учу — ten alchiks, экинин учу торт — fourteen alchiks, бештин учу — twenty-five alchiks, кырктын учу — two hundred alchiks.

In everyday life, these same combinations of words meant concepts such as several, a small number (for example, two — three, three — four, five — six). Анин чакан уйунун торундо бирдин учу болуп олтурушкан кишилер — In his small yurt, a few (a small number) of people sat in a place of honor, or Бирдин учу эле малы бар — He has a small number of livestock (three — four, five — six heads).

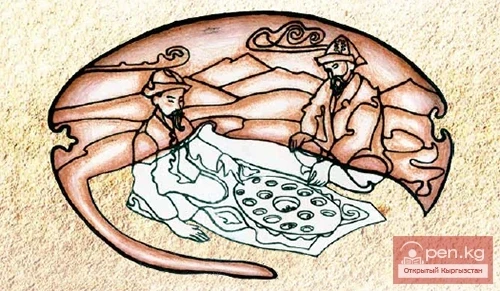

The ancient Kyrgyz game "Toguz Kumalak" or "Toguz Korgool" (ten small nuts or tokens) consists of a wooden board with 18 small holes (each containing 9 tokens) for direct play and larger holes for won tokens (nuts):

Эки атасы бар,

Он сегиз энеси бар.

Бир жуз алтымыш эки баласы бар.

Has two fathers,

Has eighteen mothers

And children — one hundred sixty-two.

The process of the game involved two partners taking turns placing tokens in a circle. The won tokens were collected in their respective pits. The game required each player to have great willpower and patience, and most importantly, immense mental concentration. During the game, opponents quickly calculated the next move or intention of their opponent in their minds, using all four arithmetic operations simultaneously.

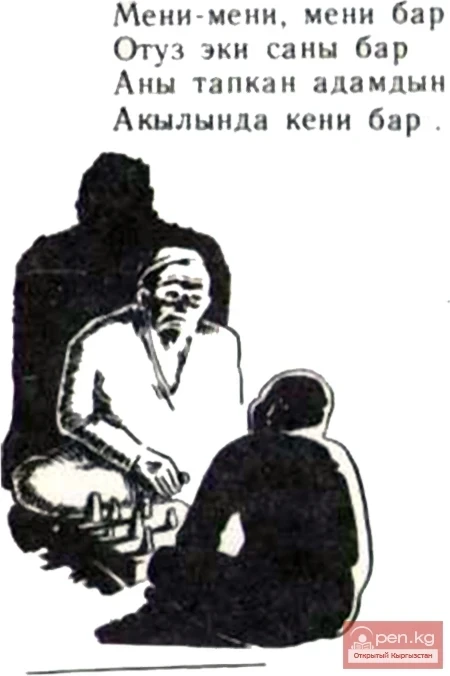

The calculation and tactics of the players were such that each of them should not make a wrong move, thereby allowing the other side to collect a large number of tokens. The player with the analytical mind and the tactics of clever moves became the winner. Another, more complex game than "Toguz Kumalak" among the ancient Kyrgyz was called "Chatyrash":

Есть фишки у меня, есть и у тебя,—

Всего их будет тридцать две.

Умный из умных отгадает эту загадку.

There is a version among the people that this very complex game of the Kyrgyz was improved by Indians in past centuries and led to the creation of chess as we understand it today. Therefore, participation in this intellectual game was mainly among adults, especially khans, beks, asker bashchylars — military leaders, есепчи, etc.

In the epic "Janil Mirza," there is an ancient Kyrgyz word conveying the mathematical concept of quantity used in counting animals — санга.

Эки санга толуптур

Эсепсиз жылкы болуптур.

When counting horses,

Their quantity equaled two san.

Since this concept did not express a specific, definite quantity, its use was associated with various difficulties, complicated by the simultaneous use of different counting systems. Alongside the decimal system, the duodecimal (based on dozens) counting was widely used, applicable to various classes of objects, particularly in measurement, which was based on comparisons with known objects — body parts, household items, etc. The practical convenience of using this last type of measurement is undeniable, but it was quite approximate.

In the course of labor activities, people studied various properties of objects. Concepts such as space, length, height, time, speed, force, and many others transitioned into modern physical science from the everyday notions of ancient people. With the development of agriculture, animal husbandry, and trade, concepts and corresponding measures of distance, length, thickness, and weight of bulk, liquid, and solid bodies were developed.

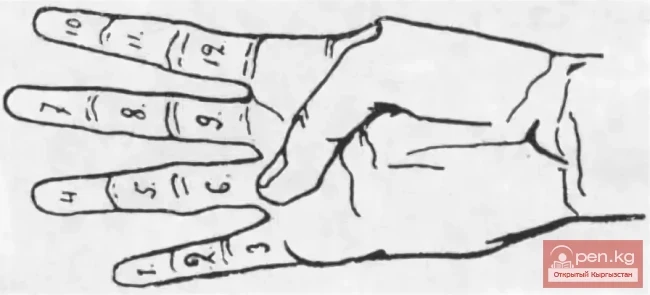

The nomadic lifestyle of the Kyrgyz, their detachment from urban civilization, and the underdevelopment of trade and agriculture determined the extreme simplicity of these measures. Initially, the length of the hand, the step, or the distance between the ends of the outstretched thumb and index finger was taken as the standard of measurement. The ancient Roman architect Vitruvius noted that initially "the basis of measures, evidently necessary for all kinds of work, was taken from such parts as the finger, foot, elbow." As a rule, measured objects were compared with already known things, items used in everyday life.

Let’s consider Kyrgyz folk measures, starting with the smallest linear units of measurement. For example, the layer of казы май — fat on meat was characterized by the following words: кылдай — with the thickness of a hair, бычактын мизиндей — with the tip of a knife, ийненин сабындай — with a needle, бычактын сыртындай— with the width of a knife, etc. The length and width of objects were measured with such measures: чыпалактай — with a pinky, бармактай — with a thumb, кийиздин калындыгындай — with the thickness of felt, таман эли — with the width of a foot, etc. The last unit of measurement was usually used to determine the fatness of the most well-fed horse, which was specially fattened to be slaughtered in winter — on days when fierce frosts prevailed or for some festive occasion (such as a feast, circumcision celebration, etc.). Other parts of the human body were also used as measures: the thickness of the palm, the circumference of the elbow, the circumference of the thigh, the circumference of the waist, the circumference of a bull at the waist, etc.

Measures of width and thickness were largely analogous to small measures of length, to which only the word узундугу was added: узундугу жарым эли — length of half a finger, узундугу бир эли — length of one finger, etc.

Карыш — a span (a quarter of a yard) was divided into small (11 —13 cm) and large (22—23 cm); a span is the distance between the ends of the outstretched thumb and middle fingers. The span was further divided into кере карыш — an outstretched quarter, мерген карыш or соом — the distance between the ends of the outstretched thumb and index fingers, укум карыш — the distance between the end of the thumb and the bent index finger. This measure was used to measure poles, wooden parts of the yurt, and fabrics. The size of cauldrons (kettle) was also measured in spans. The largest cauldron was 12 spans. In the epics "Manas," "Kurmanbek," and "Kedeykan," there are mentions of such cauldrons, and in the epic "Er Teshstuk," there is a story about a magical cauldron called кырк кулак (forty ears):

Кырк кулак казан бар

Кырк кулагы кырк жакка экен:

Тилек тилеп ачылган.

There is a magical cauldron "forty ears":

All "forty ears" open,

Wishing harm.

Other measures of length were also used: чыканак — from the elbow to the tips of the outstretched fingers, кары — from the elbow to the shoulder (this distance is approximately 40—50 cm). The width of fabric was usually determined by the measure теш жарым — from the end of the outstretched arm to the middle of the chest. There was also a measure called кулач — the length of the wingspan of arms stretched to the sides (a fathom), which was common among other peoples. The Kyrgyz measured the length of ropes, ууков — the poles of the yurt's dome, желе — the ties for foals stretched between two pegs, когонов — the sheep ties made of a long rope, the depth of зындана — the dungeon, the height of fortifications, etc. The distance between the ends of the fully outstretched arms was called кере-кулач.

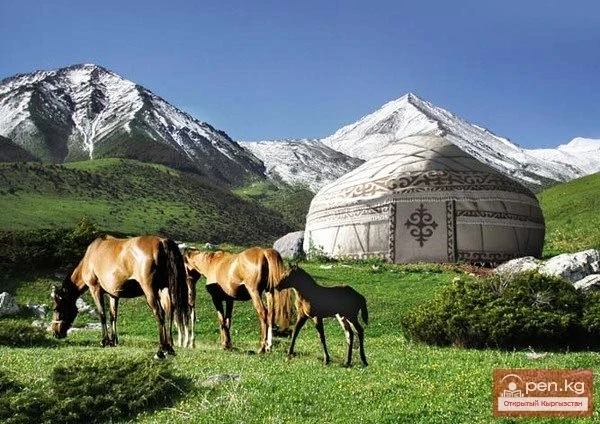

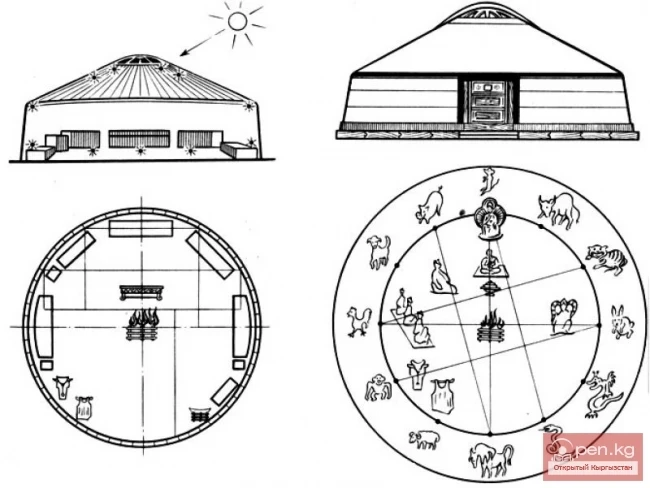

To denote length, the distance from the door of the yurt to the tara — the honored side of the yurt, which equaled 4 or 5 meters, was used. Sometimes other measures of length were used: бир кадам — the length of one step, эки аттам — the length of two jumps, etc.

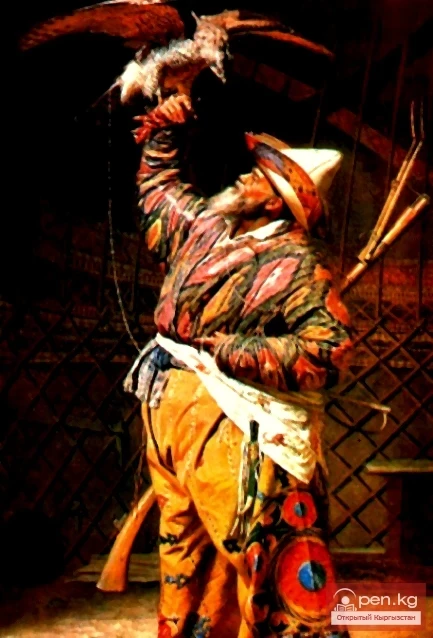

Since ancient times, a folk measure of length has been the definition of hunters regarding the distance to the target — based on the range of a bullet: бир бута атым — about 100 meters, эки бута атым — 200 meters, etc. The distance over which a person's shout can be heard, approximately equal to a verst (1.06 km), was called чакырым.

Knowing these measures of length, one could find others. Usually, the есепчи, or койчу — shepherds, who needed clever assistants, tested a child's abilities by solving (in their minds) tasks like: Аралыгы 5 чакырым жерге катары менен тыгыз тиркешкен канча ийнени коюуга болот? — How many needles can be placed closely side by side over a distance of 5 kilometers? They calculated as follows: first, they found out how many needles could fit along the length of a matchbox, then how many such boxes would make up 1 human step, and how many steps make up a kilometer was known.

Often, the Kyrgyz used the measure of length таш, which was approximately equal to eight kilometers. In the epic "Manas," it is noted:

Чымылдык кылган камышы,

Беш таш жерге угулуп

Безилдеген дабышы.

The rustling made by the reeds,

When it continuously sounds,

Is heard at a distance of five stones.

Distance was also measured by the time it took to travel it on horseback at a speed of approximately 10—12 kilometers per hour. Distances were also measured by the time spent preparing food: the time it takes to boil a kumgan — a kettle, was equal to 30—40 minutes, to drink tea — 15—20 minutes, to cook lamb meat — 1.5—2 hours, to cook mutton — 3—3.5 hours. A close distance, taking 8—10 minutes to travel, was called коз ирмемде (in a flash; before you can blink).

The fact that people used time to measure distances reflects the interrelation of two forms of existence of matter — space and time. The very idea of measuring spatial properties of the surrounding world through processes occurring over time is only possible based on the objective existence of such a connection.

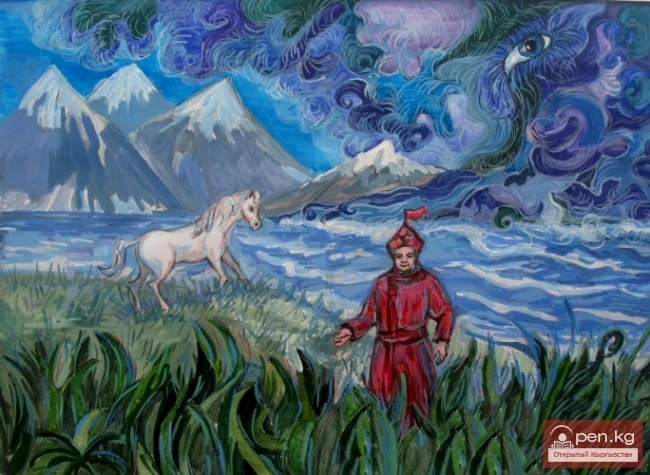

Long distances were defined by the following measures: тай чабым — the distance a yearling stallion can gallop without stopping — approximately 3 kilometers, купан чабым — the distance covered without rest by a two-year-old stallion — 5—7 kilometers, ат чабым — the average galloping distance, which is about 25—30 kilometers, etc.

Distances were often estimated "by eye," using distant landmarks — a mountain, a rock, a river, a large hill, or close landmarks — a yurt, a tree, grazing livestock, etc.

An important practical measure is area. People often had to measure the area of the yurt (the floor of the yurt), doors, arable land, pastures, and hayfields, таш короо — a stone enclosure, чырпык короо — a fence woven from sea buckthorn and other shrubs for sheep pens, etc. The following simple measures were used: алакандай — the area of one palm, уйдун ордундай — the area under the yurt, танап — about 0.005 hectares, теше — the area of one-sixth of a hectare.

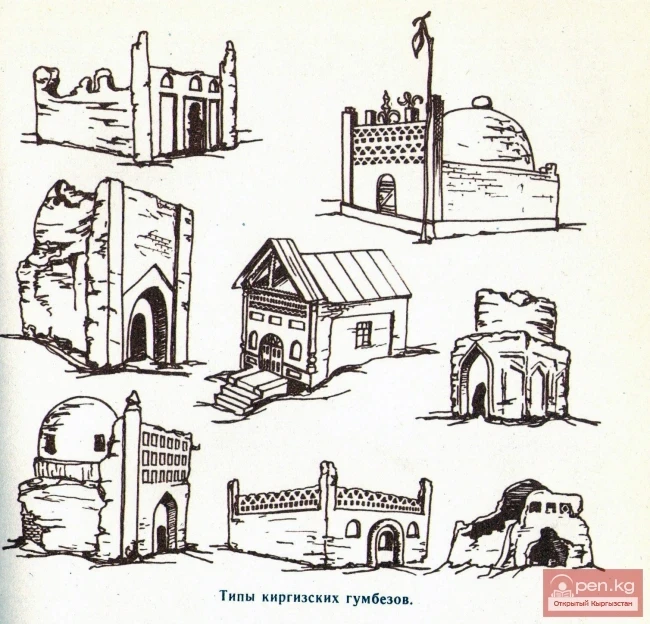

Measures of height among the Kyrgyz were almost undeveloped, apparently due to the absence of any tall structures among this people. The following measures of height were used: тушардан — up to the hobbled horse, тизе бою — height to the knee (for example, тизе бою кар — snow to the knee), киши бою — height of a human, кереге бою — height of the wooden lattice forming the walls of the yurt, уй бою бийик — height of the yurt, тоо бою — height of a camel, киши бою терен — depth to the height of a human, тоо бою ан — a pit to the height of a camel, укурук бою терен — depth with a beam, or укурук бою бийик — height equal to the length of a beam, аркан бою бийик — height comparable to the length of a rope. Ropes varied in length — 12.8 or 6 fathoms. The most commonly used ropes were 12 fathoms long. Such ropes were used to measure the height of fortifications. For example, in the epic "Manas," the fortress wall of the Kalmyks is described as being 12 ropes high, i.e., 21.36 meters. There are also units of measurement such as алтымыш кулач танап — a rope measuring sixty fathoms. Here the word танап serves as a rope, cord, etc.

The Kyrgyz had an ancient measure of height called бакса. In the epic "Manas," it is told that the enemy commander Konurbai had a very trained horse, Algara, which, fleeing from the pursuing Manas, easily jumped over a doval — a fence height of 60 баксов:

Проклятый этот конь Алгара!

Способности у него великие —

Шестидесятирядную стену

Единым духом перемахнул.

Regarding the height of mountains, they said: асман, or кок тиреген тоо — a mountain reaching to the sky.

The Kyrgyz had unique measures of weight. The quantity of meat was determined as follows: бир кесим эт or кол кесер — a piece of meat weighing approximately 1—1.5 kilograms, бир сан эт — the thigh part of the carcass, бир жамбаш эт — the leg, бир далы эт — the shoulder, бир козунун эти — meat from one lamb, бир койдун эти — meat from one ram, etc.

For measuring volumes of bulk materials, household items were used. The volumes of bulk and liquid materials were designated as follows: кыпындай — a crumb, таруудай — a grain of millet, тырмактын агындай — a white part of a nail, бир чьшчым — a pinch, бир ууч — a handful, бир кочуш — a fistful, бир кашык — a spoon, бир аяк — a medium-sized cup, etc.

Among farmers, a unit of measurement for volume and weight called байс was practiced.

The unit of weight accepted among the Kyrgyz — байс — equaled the weight of 100 grains of barley, and 100 байсов made up 3 kilograms of grain. When farmers received, lent, or sold grain, they calculated as follows: 200 байсов, which made up 6 kilograms of barley, were accepted as a unit called чакса; a larger weight measure was 2 чаксы — бир нимшек, or 12 kilograms, бир шимек — 4 чаксы, or 48 kilograms, etc.

Grain was often measured in a simpler way: they took 100 or 200 байсов of grain, poured it into some vessel, and measured the amount of grain by the height from the bottom of the vessel to the joints of their fingers. In this case, the measurement process was much faster, but the inaccuracy increased.

The quantity of grain was also measured in кап — bags, which had different capacities. The largest кап was the height of a foal and was called тай кап; its capacity was equal to one батман of wheat or 12 пудов. In folk epics, there are mentions of heroes who could eat not one батман of grain in one sitting:

Семь батманов пшеницы за раз съел

Хлебом пахнущий огромный Джолой

Sometimes these quantities were used to measure the strength of pack animals, usually camels, and less often horses.

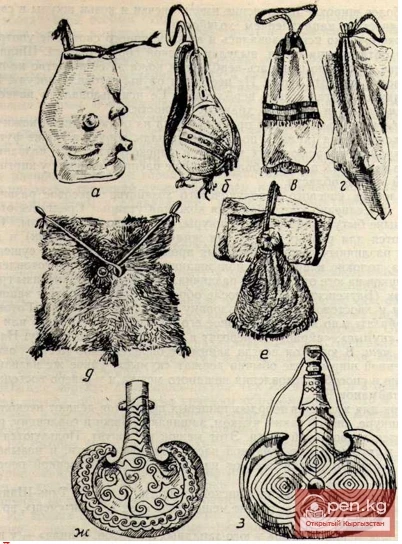

A smaller volume measure was кой кап — a bag the height of a ram, holding about 6—7 пудов of grain. Куржун — a pack bag, also served as a measure for bulk materials. The most commonly used were баштык — a small bag and тулуп — the skin of a calf, lamb, kid, etc., taken off as a sock and treated with sourdough. Bulk items were also measured in этек — the hems of a chapan, уучом — one palm, кочушом — two palms. Farmers used оро — pits for storing grain; an average-sized pit was 1.2 meters deep and 0.7 meters wide.

Ayран was measured in чаками, кумыс in сабой, a large leather bag with a capacity of up to 35—40 liters, made from the skin of six-month-old and one-year-old sheep. Milk and кумыс were also measured in коноками — leather buckets used for milking mares, as well as in burduks (shaped like flat jugs). Конок and кокоор were made from camel skin.

The quantity of liquid was also measured in чаками — wooden buckets, челеками — tubs. The largest bowl — табак had a capacity of about 10 liters, in which meat was served. All these measures were mainly used in the exchange or borrowing of products from one another.

Kyrgyz farmers measured water in кулаками. Кулак — the amount of water needed to irrigate 1—2 hectares of land.

Measures of weight, area, and also some accounting in monetary terms were mainly used in agricultural, valley areas of Kyrgyzstan, and less often in the northern mountainous regions of the Tian Shan (the spread of these measures in agricultural areas is likely due to the influence of settled peoples — Uzbeks, Tajiks, with whom the Kyrgyz conducted trade).

Every nation has gone through its own historical path, during which its national identity has formed. However, the formation of a people cannot be imagined in isolation from external influences. On the contrary, it is precisely interethnic communication that has been a constantly acting factor contributing to the enrichment of the spiritual life of nations and was a source of replenishing their knowledge about the surrounding reality. Such influence is also traced in the pre-scientific notions of the Kyrgyz related to measurement and counting.