Among the Kyrgyz, as among other peoples of the world, concepts denoting physical quantities were developed in the process of understanding the connections between phenomena, processes, and generalizing their aspects and characteristics important for practice. The formation of concepts reflects the activity and creative nature of thinking, while success in using these concepts entirely depends on how accurately they reflect objective reality. Through concepts obtained by abstraction, reality is understood more deeply by defining and investigating its essential aspects, highlighting the general, which, however, does not oppose the individual and the specific, since the general itself exists only through the separate, concrete. Since the general forms the basis of the qualitative specificity of individual objects, knowledge of it allows for the explanation of the individual and the specific. "He who knows the whole," noted the ancient Greek writer Lucian, "can know its part, but he who knows only a part does not yet know the whole."

The Kyrgyz referred to everything around them—the earth, celestial bodies, plants, animals, water, air, etc.—as жаратылыш—nature. In their view, nature existed and would exist forever.

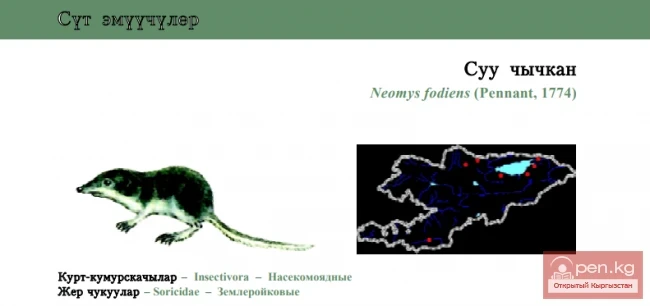

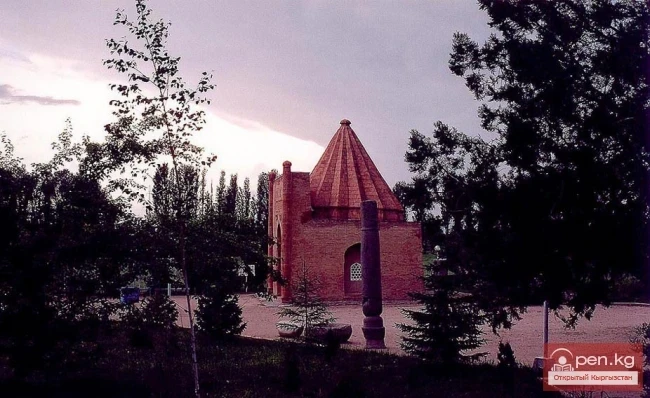

Photo 1. Zhapak. Original. Stored in the State Historical Museum of Bishkek.

The pre-scientific physical representations of the Kyrgyz can be characterized as practical knowledge that did not rise above simple, elementary generalizations; it was directly incorporated into their daily activities. Everything that occurs in nature was referred to by the Kyrgyz as табияттын кубулушу—natural phenomena. They had concepts such as кардын эриши—melting snow, кун-дун куркурошу жана чагылган—thunder and lightning, жер титироо—earthquake, мондур тушуу—hailfall, etc. People noted that bodies made of different substances (lead, copper, iron, etc.) have different weights at the same volume. Уста, зергер—blacksmiths, craftsmen who made silver items—brooches, rings, parts of harness for riding horses, etc.; hunters who used their own prepared shot knew well about нерсенин тыгыздыгы—the density of substances, and they used terms such as жумшак—soft, борпон—loose, таштай—like stone, болоттой—like steel, etc.

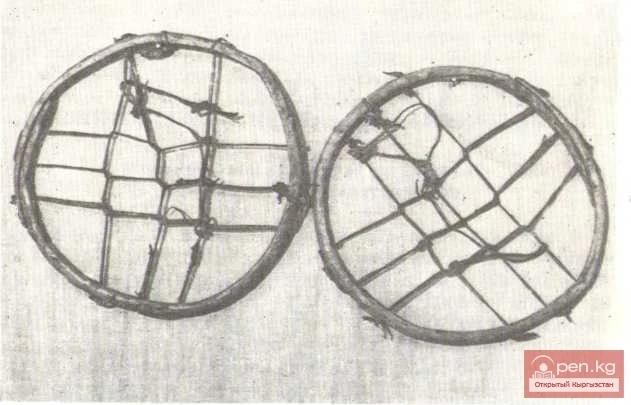

Kyrgyz hunters, since ancient times, walked on loose snow in winter using жапкак—a device for walking (but not sliding) on snow. From everyday life experience, people knew that the pressure force on the snow is less the larger the area occupied by a person. The surface area of the zhapak is five times larger than the area of a person's soles; therefore, a hunter on a zhapak exerts pressure on the surface area of the snow with a force five times less than without this device. Ultimately, empirical knowledge of this kind led to the emergence of the Kyrgyz physical concept of басым—pressure. In their daily lives, the Kyrgyz, based on knowledge accumulated over centuries, came to discover previously unknown laws of physics and apply them in practice. For example, Kyrgyz people living around Lake Issyk-Kul used уйлоп толтурулган карын—the stomach of an animal inflated with air—to dive deep into the water for various objects, not forgetting to hold a stone between their legs as a weight for faster immersion. When lacking air, the diving swimmer did not surface but breathed from the air reserve in this peculiar chamber.

When herding sheep across rivers, people acted as follows: they filled чанач—a leather bag (when filled with air, it was called турсук) and two horsemen, tying one inflated chamber to their forearms, stood in the water or swam across to the other side with the entire herd of sheep. With the help of a turzuk, even turbulent rivers could be crossed. There were other ways to use it. Horsemen would throw "…into the current, gripping the turzuk with their knees—a leather bag inflated with air, holding its opening with the left hand and working with the right hand." Some brave men demonstrated remarkable skill in this.

In a report dated May 30, 1896, an assistant to the district chief of Pishpek, who participated in the search for participants of the Andijan uprising, wrote: "The Kyrgyz swim across the turbulent Naryn on chanač—leather bags, tying themselves to the tail of a horse, while placing their clothes on other chanač."

The described facts show how years of practice in water transportation led to the establishment of a purely empirical relationship between the volume of displaced water and the carrying capacity of rafts, that is, to the practical application of Archimedes' law.

The first representations of куч—force were associated with the muscular tension of arms, legs, etc. The words кучтуу—strong or чабал—weak characterized the action of one body on another, for example, the action of жаа—the taut string of a bow on an arrow, etc. There was also another concept of force—ал. A sick or old person would complain: "Алым жок— I have no strength."

In everyday life, the Kyrgyz often encountered the force of elasticity, which they called серпилгич куч. For example, when stretching the bowstring or bending ]тундук—the hoop of a yurt, it was usually said: Тундук жасаш учун жаны ийилген жыгачта, атыш учун катуу тартылган жаада серпилгич куч бар—In the freshly bent raw wood, as well as in the taut bow, there are forces of elasticity. Adult Kyrgyz watched to ensure that children did not approach the bent tree, knowing that if the rope or belt tying the connection of the arch were to come undone, the released tree could injure someone.

The Kyrgyz used concepts such as катуу—hard, жумшак—soft, сулкулдо—to sway gently, солкулдак—elastic, etc. For example, they would say: солкулдак чыбык—an elastic whip; сулкулдоп басат—walks, swaying gently. The plate of the trap deforms significantly when compressed, creating a force of elasticity. Hunters said: the distance a bow's arrow flies depends on how hard you pull the string with the arrow.

From their own practice, people knew that a fast-running horse cannot be stopped immediately. Trainers of horses, before a race, warned a boy aged 9-11 riding a horse they had prepared: when you reach the finish line, do not suddenly stop the horse, otherwise you will fall in the direction the horse is moving, beyond its head. This statement indicates that the Kyrgyz knew about the existence of the force of inertia, although they did not have the term "inertia."

The concept of force was associated by the Kyrgyz with the concept of work. People said: Жаш келсе ишке, кары келсе ашка— When a young man comes, ask for help in work, as he is strong and powerful; when an old man comes, respect him and treat him to food. Here, the physical strength of a person is expressed through the concept of power. Elderly people would tell the young: You are stronger and more powerful than me—asking for help with some work.

In winter, during heavy snowfall and complete impassability, herders utilized the strength and power of horses. At this time, they would say: the snow has fallen to the stirrup, we need to use the power of the bay stallion; if the snow has fallen to the horse's chest, those who saw it would feel sad. After a snowfall, one of the men, riding the fattest, strongest stallion, would pave the way, for example, from the pen to the watering place or from one yurt to another.

It is known that for thousands of years, people have used the energy of moving water for various purposes. In particular, the Kyrgyz used the force of moving water to rotate a wooden drum with devices for taking the impact of water with blades. Peasant farmers on rivers with different water levels set up суу тегирмен—water mills. The Arab geographer Al-Idrisi wrote in the 12th century about the Kyrgyz: "...on this river, they have mills where they grind rice, wheat, and other grains into flour; from which they make bread, or eat them boiled without grinding; this is their food." The Kyrgyz also knew how to make a more complex device жуваз—a press-like device, with which they extracted oil from the seeds of various grains, including opium poppy. However, the existence of even such complex structures as a mill or a press does not necessarily indicate a high level of technical thinking, as the population largely relied on established traditions and prior experience. In contrast to technical thinking, traditions and experience have a quite definite, sufficiently narrow content, making them useless outside a strictly defined sphere of application. Technical knowledge and engineering thinking are characterized by their applicability to solve a wide variety of, including completely new tasks.

Mill. Mid-19th century.

Among the Kyrgyz people, terms such as оор—heavy, салмактуу—weighty, женил—light, жеп-женил—very light, etc., have long been in use. The beret, an expert in his field, would set a mandatory condition before a decisive race: Атты жецил балага чаптырыш керек— A light boy must go to the race.

When building bridges over rivers or suspension bridges over gorges (for driving livestock to the summer pastures—alpine and subalpine pastures—and back to winter quarters, herders made sturdy crossings and bridges), the Kyrgyz realized the existence of оордук куч—the force of gravity. At the same time, people believed that the strength and durability of bridges depended on prayers and sacrifices to the Almighty; they asked the protector of waters—суу башындагы Сулаймана—to kindly consider the needs of the nomads, not to send terrible, destructive floods, etc. This is also reflected in the folklore of the people.

Bridge. Mid-19th century.

The ancient Kyrgyz also had notions of the force of friction—сурулуу. Places where ice formed on the path of herding livestock were preemptively sprinkled with ash, earth, or sand, and sometimes covered with felt. This knowledge was also used by hunters, who often walked on rocks, cliffs, and glaciers in search of game. They, in particular, wore темир туяк (iron hoof)—a special sole with iron spikes for shoes similar to "crampons," sometimes called темир покой—iron spikes.

The ancient Kyrgyz had concepts reflecting varieties of the inclined plane, for example, шына—a wedge (the main part of piercing, cutting, and planing tools—such as бычак—knife, балта—axe, буурсун—plow, etc.). The buursun was made from durable wood.

Expressions such as: "Чыкпаган шынааны озундой шынаа менен ургулап чыгар"—A wedge drives out a wedge, and others, have long been common in everyday life.

Iron hoof similar to 'crampons'

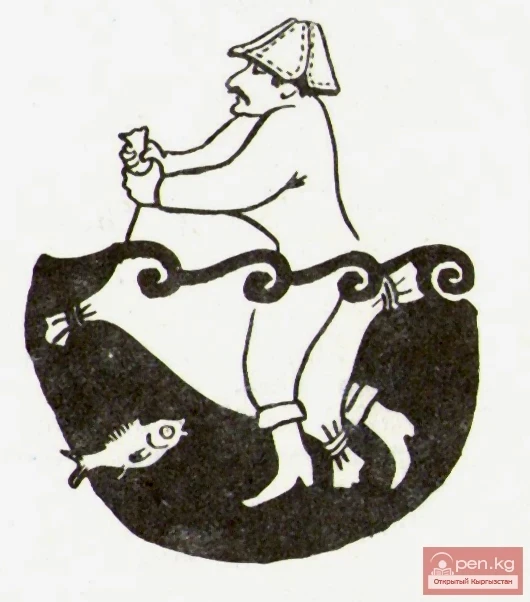

Hunters used салмоор—a sling as a weapon. They did not know the physical laws of motion of bodies thrown at an angle to the horizon, but they had a clear understanding of the dependence of the distance of flight on this angle and on the magnitude of the initial speed of the stone that flew out after being launched from the salmoor.

Boys (12 years and older) used salmoors to scare away numerous sparrows from fields sown with millet, wheat, and barley.

The initial elements of practical, empirical knowledge of people have always been connected with the production of tools, hunting, and the ability to use them. F. Engels wrote in "Dialectics of Nature" that the transition from crude stone tools to bows, arrows, and polished stone tools required long-accumulated experience and persistent intellectual labor.

In the process of such knowledge, like playing the komuz or swinging on swings, people understood what титироо—the vibration of a sounding string and селкинчектин термелиши—the oscillation of swings were. It seems that it is from these activities that the origins of the concept of термелуу—oscillations arise. Observing the waves on the surface of water bodies, people would say: the lake is stormy. Countless times, people saw that if the water surface was smooth as a mirror, and someone threw a stone into the water, then waves would spread in circles from the point of its fall. Thus, the concept of толкундар—wave appeared among people in the course of their observations of processes occurring in nature. Today we know from physics that the propagation of wave oscillations in a certain medium represents wave motion, the deviation from a stable position to the greatest distance is the amplitude of oscillations, and oscillations that completely repeat the previous ones over a certain period of time are called periodic oscillations.

People knew that суйлошуу—speech, which allows people to communicate, consists of a series of successive добуша—sounds. The voice of one person differs from the voice of another, one word from another; people perceive the subtlest shades of the human voice—ун—joy, sadness, anger, etc. Proverbs and sayings exist in the people that reflect the character of a person, their fate through speech, for example: beware of a person who speaks with mockery, do not trust a woman who speaks in a man's voice.

People distinguished not only the noise sounds arising from a shot from a flintlock rifle, the explosion of homemade gunpowder, the impact of heavy stones falling from heights, thunder after чагылган—lightning, etc., but also musical sounds produced by various folk musical instruments— кыл кыяка, sometimes комуза—a three-stringed plucked musical instrument, темир комуза or жез комуза—a jaw harp (usually played by women), чоора—a shepherd's flute made from a hollow stem, чымылдыка—a whistle, сыбызгы—a reed pipe, сурная—a wind instrument similar to a flute (an essential attribute of the Kyrgyz in military campaigns).

The ancient Kyrgyz were aware of the concept of ундун бийик-тиги—the pitch of sound, as well as the fact that sounds of the same pitch produced by singers and akyns differ from each other by the special quality of жумшак ун—softness of voice or чанырык ун—sharpness of voice; they distinguished voices: жоон ун—bass, ичке ун—high thin voice, for example: кыздын сыбызгыдай ичке уну—the voice of a girl is thin like a flute; чыйылдак ун—analogous to mezzo-soprano, катуу чыккан ун—soprano, ото бийик чыккан ун—tenor, конур ун—low voice, сыбызгыган ун—piercing.

The Kyrgyz knew that sound could be transmitted through the ground. This is mentioned, for example, in the epic "Er Teshstuk." One of its heroes, жер тыншаар Маамыт—Maamyt, listens to sounds and determines the events occurring based on their character.

The ancient Kyrgyz noted that depending on the conditions, the same substance can exist in катуу—solid, суюк—liquid, or буу турундо—gaseous states. In particular, they used the concept of муз—ice, суу—water, and суу буусу—water vapor. Since ancient times, people have observed the change of the aggregate state of substances in nature: water evaporates from the surfaces of lakes and rivers, and when the water vapor cools, dew, snow, or fog forms. Year after year, they saw how in mountainous areas, rivers and lakes completely freeze in winter (the only exception being Lake Issyk-Kul).

To denote the phenomenon of liquid evaporation, the Kyrgyz had the term буулануу (for example, people observed how puddles formed after rain evaporate, and washed clothes dry due to the evaporation of water).

Кайноо—boiling has been empirically known to people since they learned to cook food over fire.

The qualities of liquid substances were defined by the Kyrgyz with the following words: тунук—transparent, кок кашка—clear, for example: кок кашка башат—very clean spring, ылай—dirty, коюу—thick, суюк—liquid, etc.

To denote a natural phenomenon such as a rainbow, the Kyrgyz had terms кок желе or Асан-Усен, and often жез кемпирдин желеги. The colors of the rainbow were divided into кызыл—red, кызгылт сары, and sometimes курумшу сары—orange, сары—yellow, жашыл—green, кок—blue. Of course, the Kyrgyz did not know that daylight has a complex structure. For them, the rainbow is the banner of жез кемпира—Baba Yaga in the sky, while they noticed that the rainbow appears when it rains on one half of the sky and the sun shines on the other half free of clouds.

In everyday life, in addition to the mentioned colors, they also distinguished карат—black, без—gray, чымгый кара—black as soot, жашыл сымал—almost green, etc. When determining the color of domestic or wild animals, they would say: карат айгыр—black stallion, без айгыр—gray stallion, кок кызыл—gray with dark gray spots, карат кызыл—gray with noticeable black speckles, сары кызыл—gray with yellow (yellow speckles on a white background), ак кызыл—light gray, кызыл буурул—dark gray, кызыл ооз (of a horse)—red-mouthed, with pink lips.

Thus, the character of the life of nomadic Kyrgyz contributed to the development of their natural observation skills and the formation of concepts about the properties of objects and phenomena that were significant in everyday practice. These representations were predominantly discrete and selective in nature, and their systematization was still in its infancy, which is generally characteristic of empirical knowledge. Overall, it can be considered that the sum of the Kyrgyz's representations about the physical properties of natural objects was sufficient to support various types of their practical activities and to solve the problems arising in the course of it.