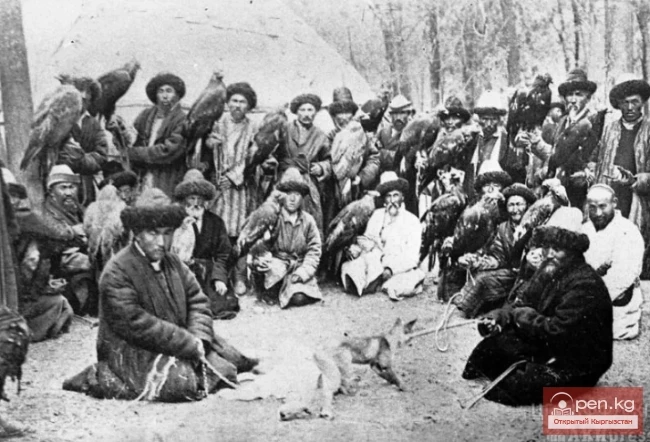

Hunting Techniques and Division of Game.

The Kyrgyz hunted both on horseback and on foot. In deep snow, they wore special stepping skis called zhapka, which significantly eased movement. They hunted large herbivores living high in the mountains either collectively using ambush methods known as bukturma or individually.

The bukturma or tosot method (in Aksy and Chatkal) was carried out as follows. Participants were divided into two groups; the first group, aidakchylard, consisted of riders known as "karasanchy," who were to stealthily approach the animals from behind and drive them toward the second group, mergenchiler, which included experienced shooters positioned in an arc, ready with their rifles (Aytaliev, 2011, p. 146). If the animals ran in the wrong direction, hunting greyhounds known as taigan were released to drive the game into areas where movement was difficult. From there, the dogs would bark, signaling their owners, who would then shoot the animals.

The method known as salburuun involved leaving a campsite for an extended period, during which the meat of the game was prepared for future use. This method also served as a form of sporting entertainment. When preparing for such a hunt, they stocked up on food azyq, prepared equipment and clothing, and gathered transport animals. During the hunt, they used caves utskur as shelter tunok. At night, they would light a fire to scare off predatory animals. In this refuge, they would leave food for other hunters who might find themselves there, hanging it on the walls or ceiling, along with warm clothing.

V. I. Kushelevsky describes a peculiar simple method of hunting wild boars in winter. The Kyrgyz would try to drive a herd of wild boars onto the ice, knowing that the animals would become helpless. Since wild boars cannot take a step on slippery ice, hunters would kill them with thick clubs and axes (Kushelevsky, 1890, p. 315).

When hunting for marals, techniques such as tracking and lying in wait were often employed. As P. I. Shreider writes, "lying in wait" comes from the word "to lie." The Kyrgyz, having determined where a maral might come to drink or appear, would lie down on the leeward side in thick grass, completely burying themselves in it. These hunters would only emerge to eat when they were convinced that the animal would not appear for a long time (Shreider, 1893, p. 184).

Hunters had a variety of tools and weapons made from both improvised materials and purchased items.

Experienced hunters successfully used traditional techniques during the Soviet era. Those who were well acquainted with the feeding, resting, and watering places of wild boars often hunted by stalking, which required endurance, patience, and the skill to approach the boar quietly for a sure shot. The stalking method was also used in hunting marals during grazing, and they were shot while visiting salt licks—either natural or specially arranged for this purpose (Hunting and Commercial Animals of Kyrgyzstan, 1969, pp. 84, 95).

The game was divided and distributed among the hunters according to folk tradition: those waiting below would lower the carcasses and butcher them near the river. The rules for distributing pieces of meat had local variations. For instance, among the northern Kyrgyz, distribution was based on age: the oldest would receive the tailbone uch, the next would get the hind leg san, followed by the tubular bones from the front part. The brisket tesh and skin teri were to be received by the hunter who shot the animal. In the Ak-Suu and Chatkal regions, pieces of game were evenly distributed among all participants. The skin was given to the person who butchered the carcass, along with the vertebrae atlanty ooz omurtka and the head keldy. The brisket was also received by the hunter who shot the game, as was the case for the Kyrgyz in the northern part of the republic.

According to tradition, upon returning, the hunter was to share a piece of meat with everyone encountered and hinted at this, uttering the words shyralga (the hunter's gift from the catch). "There were cases when hunters distributed all the meat obtained during the hunt in this way" (Abramzon, 1971, p. 96).

Commercial Animals of Kyrgyzstan in the Early 20th Century.