Hunting Dogs and Birds of Prey.

Even in the early Middle Ages, specially trained dogs served as drivers (Khudyakov, 2010, p. 173).

Training and using dogs was an important part of traditional hunting (Aitaliev, 2009, pp. 110-117).

In both individual and collective drives, greyhounds were often used, distinguished by their speed and keen sense of smell; they were fierce yet obedient. Another breed of hunting dog among the Kyrgyz was the dorëgoi.

According to legends, the patron of hunting dogs was kumayik, known for its strength, bravery, and hunting prowess.

The Kyrgyz raised these dogs from when they were puppies. At the initial stage, they were well-fed for rapid growth. Training for hunting began after a few months. Initially, they were released on hares to assess their potential. Then the hunter would take the dog hunting, putting a collar on it. However, during the first outing, the greyhound was not released on large wild animals. The dog was fed with the blood of a hunted ibex. The next day, it was not fed (Aitbaev, 1959, p. 96).

Kyrgyz taigans were known for their endurance and persistence in pursuit. The experienced ones were well aware of animal tricks and could sense the scent of potential prey. They proved themselves in hunting mountain goats, roe deer, wolves, foxes, hares, etc. While pursuing an animal, such dogs would signal their owners with their voices, who would then guess which animal they were chasing.

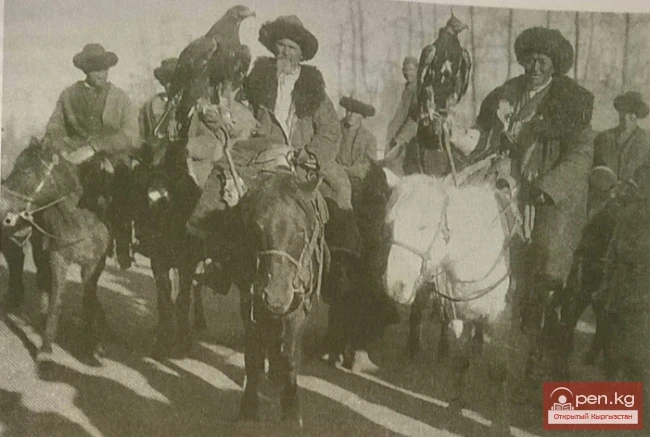

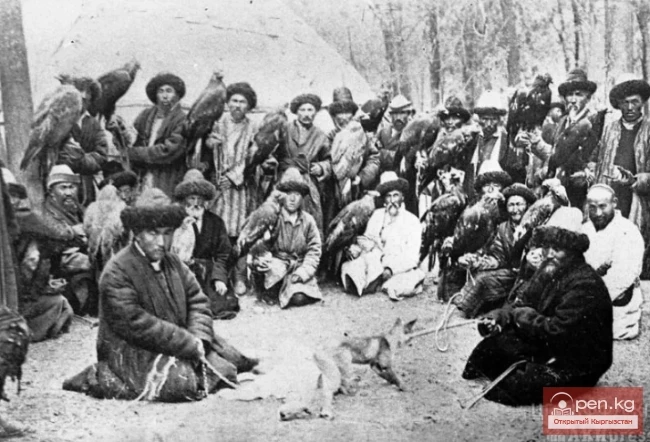

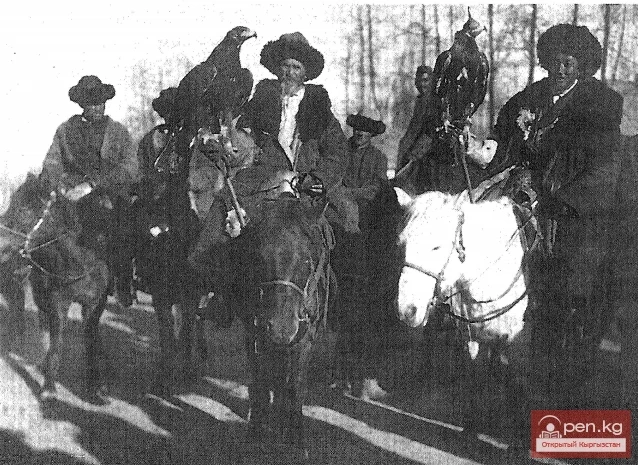

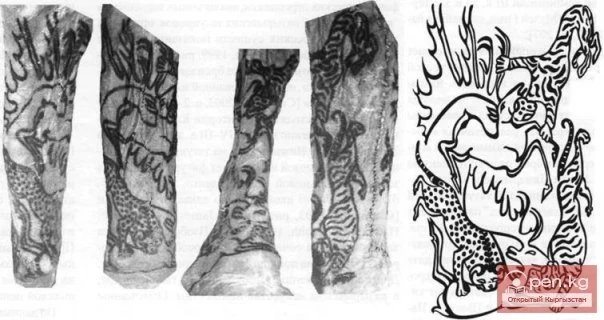

Traditional hunting with birds of prey has roots in a distant historical past. This is evidenced, in particular, by scenes depicted in petroglyphs in the Kek Say area of the Tien Shan (Khudyakov, Tabaldiev, Soltobaev, 2002, p. 129). In the Middle Ages, such hunting was a symbol and an essential attribute of state power. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, researchers noted that the Kyrgyz were excellent fur hunters and natural hunters.

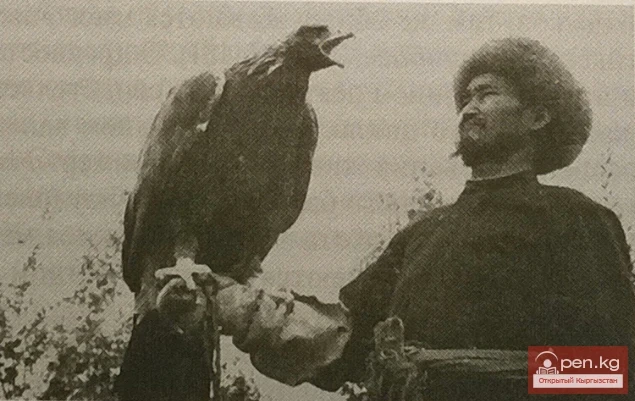

"The favorite hunting of the Kyrgyz is falconry; by training a special breed of white eagles, they hunt with spears, and wild boars are caught with the help of dogs in drives and are captured alive" (Stokasimov, 1912, p. 105) - F.A. Fielstrup wrote: "A fairly complete assortment of tools and equipment for catching birds of prey, their taming, training, and care reminds us of the widespread nature of hunting with eagles and falcons" (Fielstrup, 1925, p. 53). According to M.T. Aitbaev, hunting with birds of prey among the Kyrgyz had both a sporting-amateur and commercial character. Amateur hunting involved birds of prey such as hawks (kush), falcons (tuygun), golden eagles (itelgi), and gyrfalcons (shumkar), which caught birds suitable for food. The targets of hunting with these birds included ducks, geese, cranes, partridges, bustards, and others (Aitbaev, 1959, p. 98).

Hunting with the golden eagle had exclusively commercial significance. Hunting with the golden eagle was conducted on foxes and wolves. This bird was also used to hunt animals such as corsacs, badgers, roe deer, mountain goats, hares, wild boars, gazelles, mountain rams, martens, and others.

Hunting with birds of prey was practiced by both the upper classes and the poor. For the wealthy, entertainment was the main goal, while for those from lower classes, birds of prey were an important means of providing for the family and community (Soltonoev, 2003, p. 403). One eagle hunter from Issyk-Kul told G.N. Simakov: "He caught many foxes with his eagle, but mostly gave them away to relatives, friends, and acquaintances from his aiyl, where out of sixty yurts, there were only two eagle hunters, who bore a significant burden as dictated by tradition" (Simakov, 1999, p. 43).

The domestication of such birds as vultures, eagles, golden eagles, falcons, and harriers by the Kyrgyz was reported by authors from the late 19th century (Kostenko, 1880, p. 43; Zelands, 1880, p. 1). The presence of different species of birds of prey significantly expanded the possibilities and added variety to hunting methods using them (Simakov, 1989, p. 30).

Hunters managed to train and use the magpie, which was capable of alerting its owner with its chatter about the presence of wild animals. It was also used to gather information about impending threats to be prepared to repel danger. Kapalan Duyshonbaev from the Alai district of Osh region continues this tradition today (Aitaliev, 2011, p. 143). The fabulous bird of prey, possessing excellent hunting qualities, was called buudaiyk in oral folklore (Biyaliev, 1967, p. 29).

The outstanding storyteller of the epic "Manas," Sayakbay Karalaev, also known as an eagle hunter, listed local names for golden eagles: kaldyr kanat-muz murut, kelte, zhanboz, chokunun karasy, molor, karachik, zhelduu syrgak, zhelbegay syrgak, and others.

The Karachik possesses excellent hunting qualities - the flap of its wings, its fearsome appearance in flight, and its loud voice have a frightening effect on animals and even on humans (Karalaev, 1952, p. 8). B. Soltonoev distinguishes 65 varieties of birds of prey, of which 19 are classified as the best (Soltonoev, 2003, p. 396). The Kyrgyz evaluated birds of prey and highlighted characteristic features based on appearance, eye color, and other finer parameters and properties (Jacquesson, 2000, pp. 301-313).

People who trained and used birds for hunting, known as "burkutchu," were respected in society. Sayatchy - this term referred to those who professionally caught and trained birds of prey. The transfer of a trained bird from hand to hand was considered undesirable and dangerous. As S. Karalaev recalled, daring to take his father's eagle hunting in his absence, he barely escaped an attack from it, putting a hood on it with the help of his father's companion.

Burkutchu were well-versed in the technique of retrieving game after the bird of prey had caught its prey with its powerful claws. The hunter would gallop to it immediately to prevent it from tearing apart the prey. By enticing it with a piece of meat, he would put a hood over the bird's head, covering its eyes, which calmed the feathered predator.

Prohibitions, Beliefs, and Knowledge.

True hunters treated game as domestic animals, cared for their populations, and established seasonal hunting prohibitions, the violation of which was sharply condemned by society. According to beliefs, misfortunes and troubles that befell hunters and their families were explained by violations of prohibitions and rules. Such notions were reflected in epics, legends, and traditions, and they have been well preserved to this day. Thus, according to legend, the accurate shooter Kozhozhash perished from the supernatural force of the wild gray goat (sur echki) he killed (Simakov, 1998, 1999; Akmataliev, 1999, p. 64; Biyaliev, 1967, p. 68; Yudakhin, 1985, pp. 43, 44).

Based on centuries of empirical observations, people concluded that exceeding permissible limits could disrupt the fragile ecological balance. Traditional beliefs and notions played an important regulatory role in this. In mythological concepts, there existed a patron of all wild ungulates - kayberen, who protected and increased their populations. People who allowed excessive extermination, according to the beliefs of the people, would inevitably be punished by the patron. Hunters adhered to an unwritten law that stipulated acceptable limits. During the calving period, there was a prohibition on shooting pregnant animals, mothers with newborns, and during the rut, on males (Makelek Omurbai, 2011, pp. 312, 313). Totemic beliefs also served as a limiting mechanism, restraining hunters and preventing them from exterminating game in the heat of excitement. Animals and plants that provided food for people, the ability to exist, and to engage in agriculture naturally became one of the first objects of veneration (Zhumagulov, 2005, p. 21).

Hunters possessed a variety of empirical knowledge about the surrounding nature and developed some measures of distance, speed, etc. In the mountains, they could accurately determine where and when avalanches and rockfalls might occur, knew the degree of danger, the height at which birds fly, and the running speed of various wild animals. A distance of 100 meters was denoted by the term "bir buta atym," 200 meters - "eki buta atym," and so on; this measure of length became common and was used by the entire population.

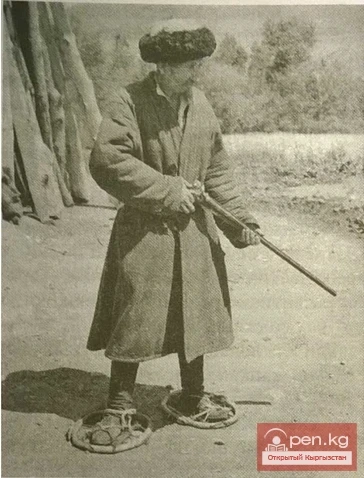

Tools and Weapons for Kyrgyz Hunting in the 19th - Early 20th Century.