Kyrgyz Ail of Past Centuries

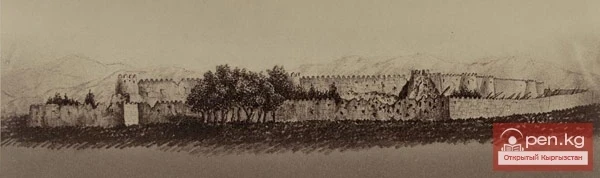

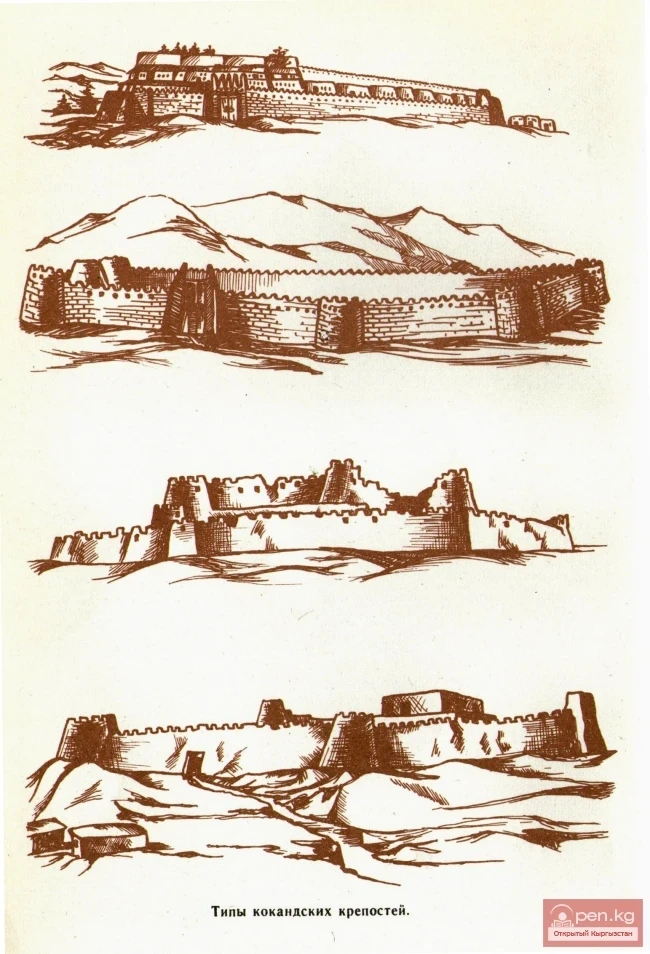

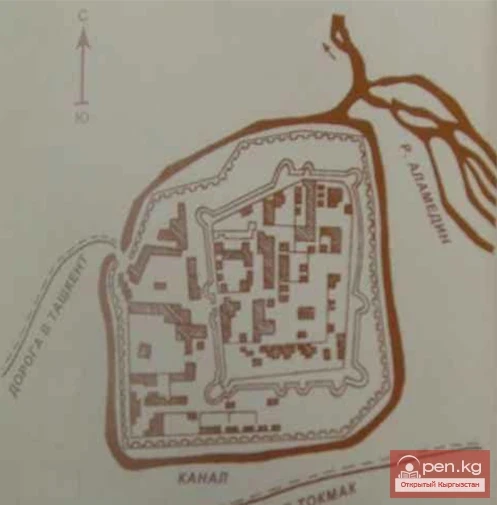

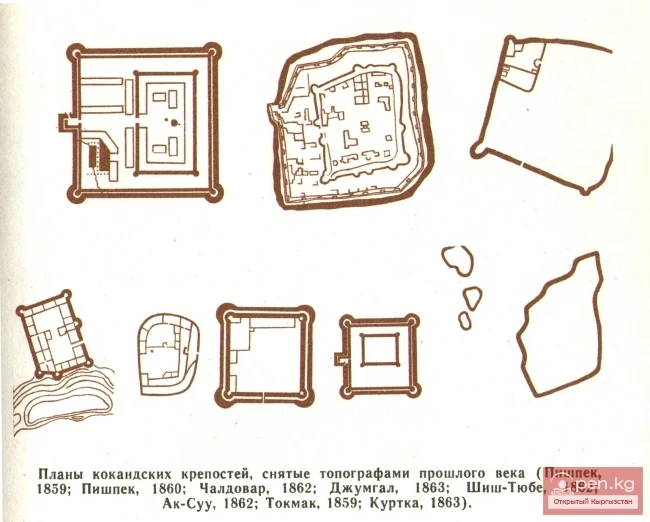

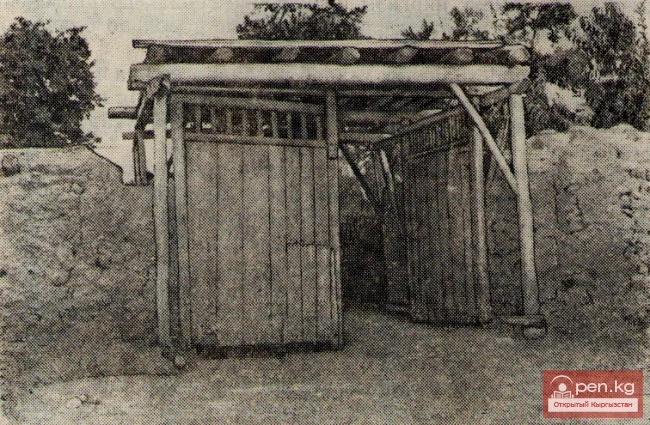

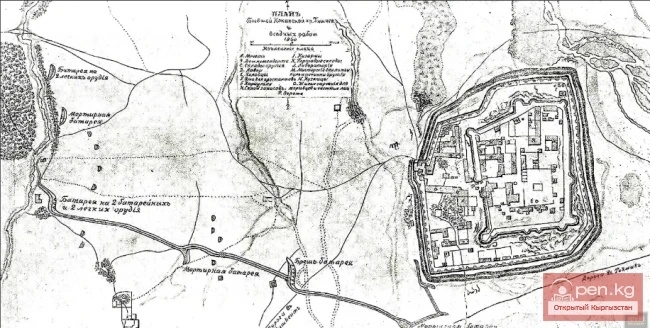

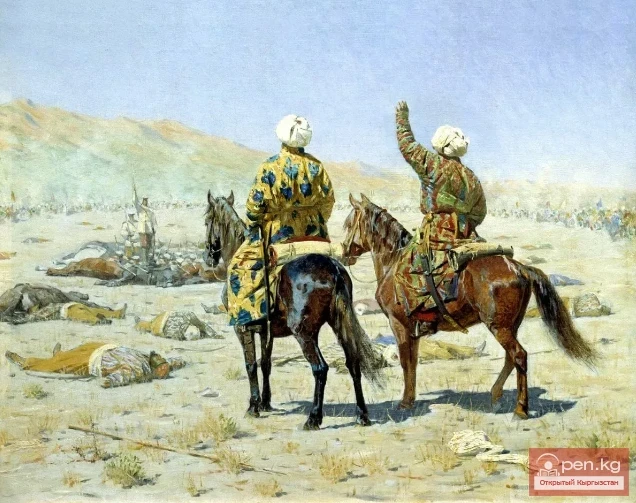

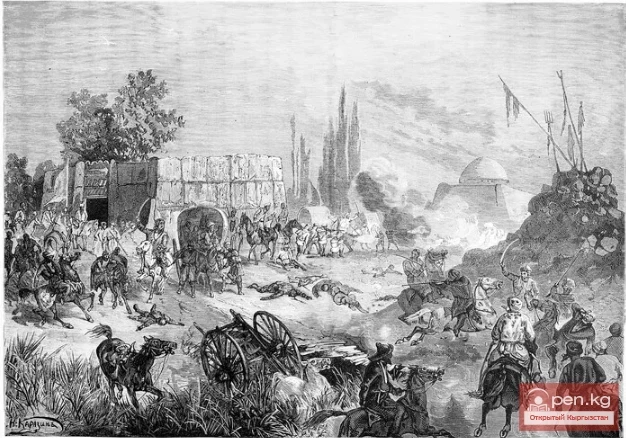

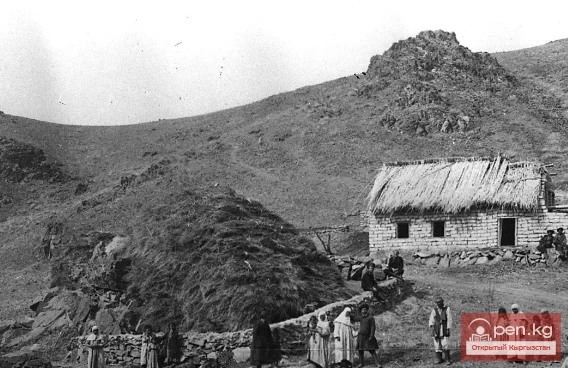

The Kokand fortresses, even large ones like Pishpek, could not serve as a base for the formation of settled settlements, as they were perceived by the Kyrgyz as a symbol of khan's oppression and were destroyed during Kyrgyz uprisings. However, even in the surviving fortresses, from which the Kokand conquerors were expelled, the Kyrgyz did not settle and avoided them in every way, as they reminded them of the cruel khan's arbitrariness. In the southern regions, during the Kokand period, due to the transition of the Kyrgyz to semi-sedentary and sedentary lifestyles, kishlaks similar to the settled settlements of the Uzbeks began to appear. In the Fergana Valley, around Osh and Uzgen, kishlaks such as Mady, Kurshab, Djigda-Mogol, Kara-Bagysh, Kara-Bulak, and others were formed. In the Pre-Issyk-Kul region, in the Juu Valley, Bugin's manap Borombai had something like an estate consisting of adobe buildings, a grain storage facility, and a mill. The estate had a vegetable garden and two small orchards. The buildings and caves on the right bank of the Juu River were surveyed by Semenov-Tyan-Shansky. "One of these caves," he wrote, "served as a storage for the mill where Borombai ground his bread.

The interior of this cave was heavily soot-stained... The largest of the caves was enclosed by an artificial stone fence, cemented with clay. Near the caves were the remnants of Borombai's fortifications."

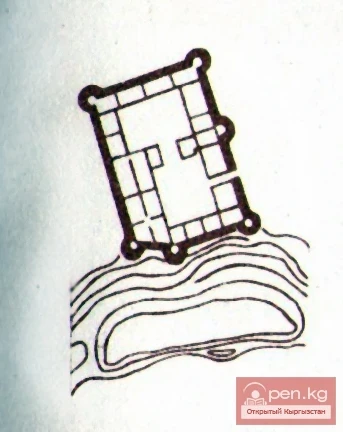

During the field season of 1978, while exploring the Chuy Valley, archaeologists stumbled upon traces of an older wintering site. Its location was convenient for housing and livestock breeding. However, no traces of a permanent dwelling were found. Most likely, the dwelling was a yurt, which was apparently set up on the ruins of a medieval settlement that rose above the marshy area overgrown with reeds. Traces of economic buildings, particularly a granary, remained. For the construction of this facility, bricks from a dismantled monumental structure dating back to the 11th-12th centuries were used.

However, the masonry was poorly executed, the walls turned out to be fragile and collapsed. To this day, only the western wall remains.

Evidently, the tumultuous life of that time, associated with constant raids and struggles, led to the wintering site being burned, as evidenced by the remnants of a large amount of burnt millet. Besides the granary, there was apparently a pen for livestock at the wintering site, as indicated by the remains of juniper logs. Archaeologists discovered a clay mold for casting bullets for a carbine and a lead ball bullet at the wintering site. Its caliber was slightly larger than those bullets cast in the found mold. But the most significant find was fragments of imported porcelain dishes with rich painting. These allowed dating the wintering site to the late 17th - early 18th centuries.

The huge pen (koroo) for livestock, a large stock of millet, imported dishes, and bullets for rifles allow us to conclude that the wintering site discovered by archaeologists on the territory of the Belovodskaya Fortress belonged to a Kyrgyz feudal lord or bai.

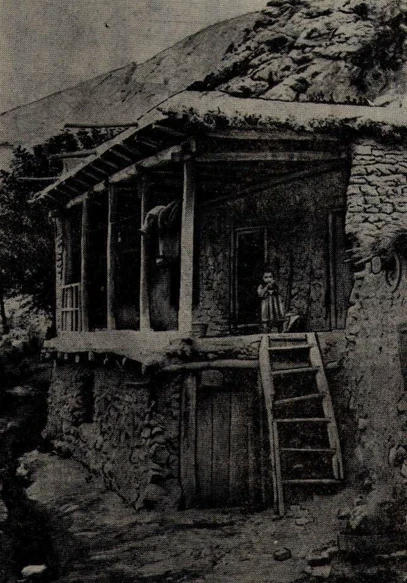

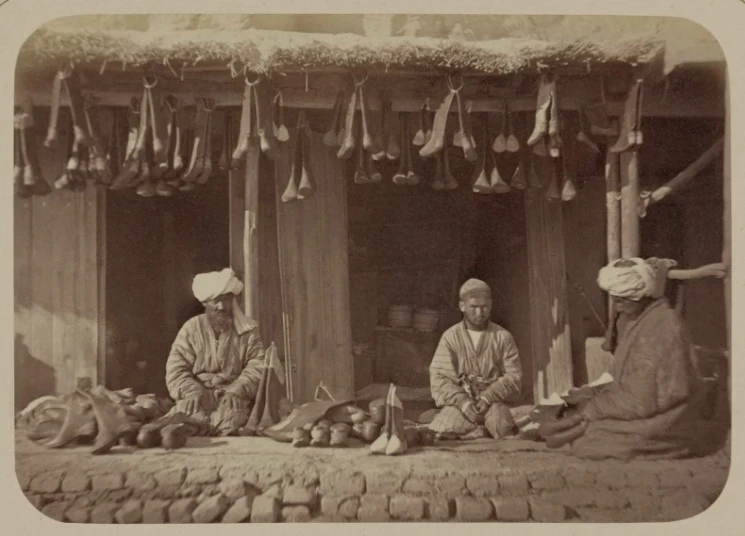

During a trip through Western Fergana, which was part of the Kokand Khanate, in the Kyrgyz village of Kara-Bulak, A. P. Fedchenko was particularly struck by the contrast between the Tajik-Uzbek kishlaks of Fergana with their rich gardens and numerous fields and the Kyrgyz villages, whose population continued to engage mainly in livestock breeding, but already in a seasonal-pastoral manner. In relatively young Kyrgyz villages, agriculture was also beginning to spread. On the way to the village of Shahimardan (modern Khanabad), Fedchenko noted: “...on the slopes of the northern mountains, Kyrgyz encampments were visible: a group of adobe houses with shelters for livestock. In the hollow were fields of wheat, not irrigated from canals, so-called lyalmi.”

In Kara-Bulak—this wealthiest Kyrgyz wintering site (kyshtoo)—the traveler saw small fields sown with barley, millet, and alfalfa, which, however, were significantly inferior to those of the Tajik-Uzbeks. “Perhaps,” wrote A. P. Fedchenko about the Kyrgyz, “they have recently begun to engage in agriculture, but still their backwardness compared to the Tajiks or Sart living next to them can be attributed to the fact that agriculture remains a secondary occupation for them. Those who have nowhere to pasture their livestock engage in it. Wealthy people sow small fields and, leaving them under the supervision of some bai, go to the mountains, from where they return for the harvest...” The Sart, the Tajik, constantly work on their fields from February to autumn, hence the difference in vegetation and harvest is evident.” In general, even such Kyrgyz settlements were singular.

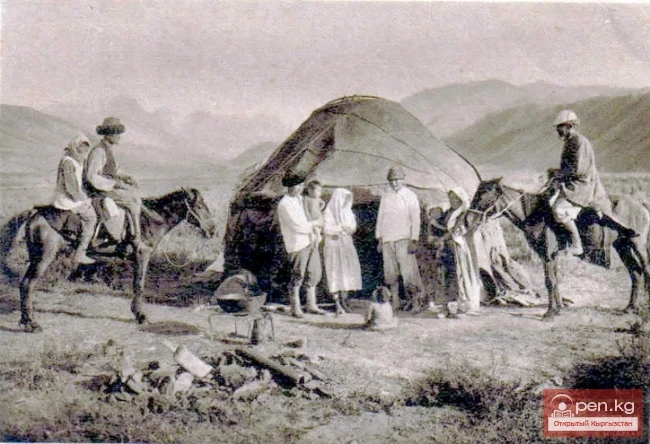

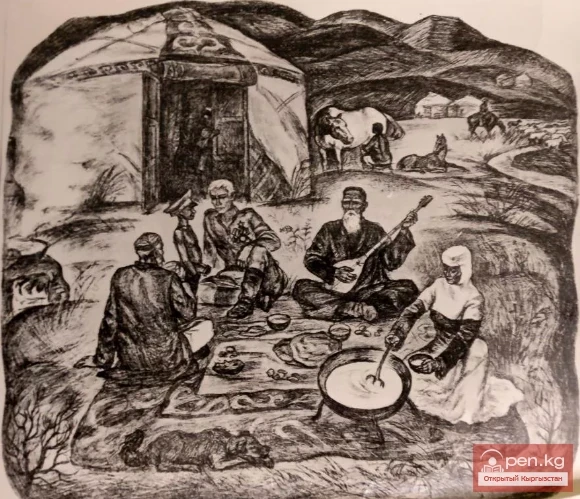

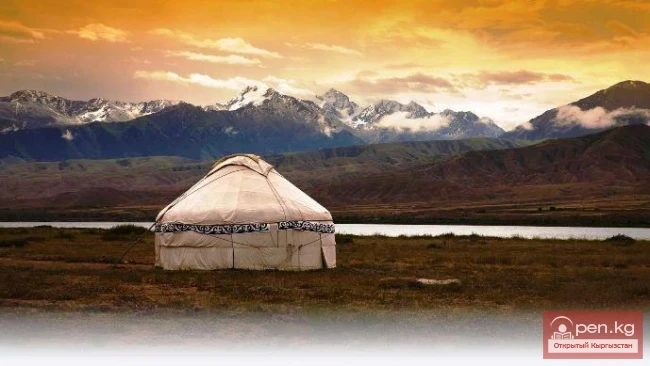

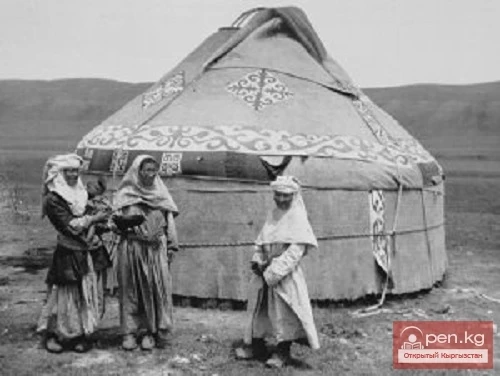

More characteristic was the settlement in ails. During his trip through the Tian Shan in the middle of the last century, P. P. Semenov left a record: “The entire flat area between the turn of the Chu and the shore of Issyk-Kul was occupied by an innumerable multitude of Kara-Kyrgyz yurts, evidently, almost the entire tribe of the Sarybagysh gathered here in camps near the aul Umbet-Aly. Finally, we reached his aul. Here we were greeted by a beautiful yurt, hastily prepared for the guests of Umbet-Aly. Rich carpets were spread in the yurt.”

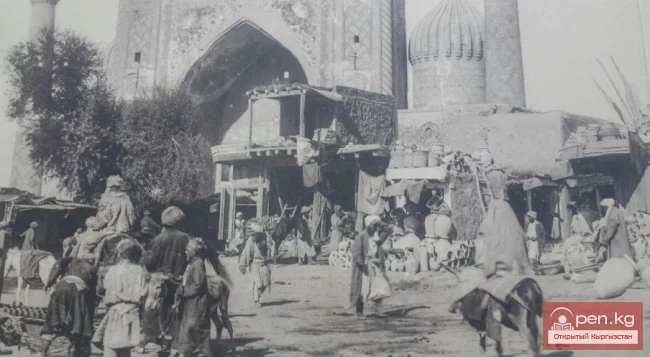

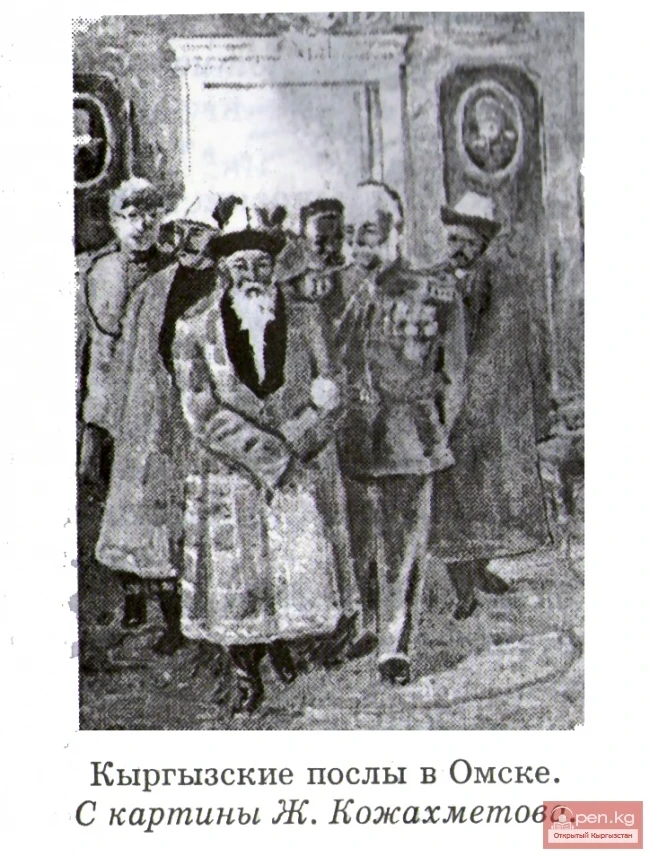

The population of ails, kishlaks, and fortresses in Kyrgyzstan before voluntarily joining Russia was generally ethnically homogeneous. Only in two Kyrgyz cities—Osh and Uzgen—did Uzbek populations also reside. At times, they predominated in numbers.

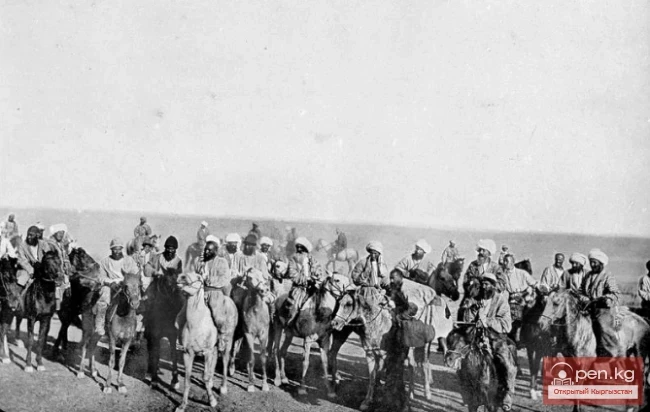

The type of settlement among the Kyrgyz underwent changes depending on historical conditions. Drawn into internecine wars by their own feudal lords and subjected to attacks from feudal lords of neighboring countries, the Kyrgyz population was forced to unite and live in large ails—communities primarily formed by kinship—until the 1850s-60s. According to G. S. Zagrjazskiy, until the mid-19th century, "the Kyrgyz always stood in large auls, with up to 200 and more yurts."

The prominent Russian Turkologist Academician V. V. Radlov, who traveled to Northern Kyrgyzstan in the 19th century, wrote: “The Kyrgyz settled not in ails, but in tribal associations, with the yurts of the families within them stretching in a continuous line along the riverbank for twenty or more versts in summer, while in winter they occupied a certain mountainous area.” “Such large settlements of nomadic Kyrgyz,” Radlov further writes, “were primarily caused by the need for protection against frequent military attacks at that time.” Radlov notes that when the threat of military clashes passed for the Kyrgyz who voluntarily joined Russia, the large settlements began to split into separate ails.

The size of an ail was not constant. In winter, residents settled in a few yurts arranged in a circle in the mountain gorges. In the center of the circle was the ruler's yurt—ak ordo—protected on all sides by the yurts of his subjugated tribesmen from external enemies. During the migration to seasonal pastures (spring, summer, and autumn), the ail would split. Poor herders of one ail, having a small number of livestock, often united and conducted collective grazing. Therefore, they settled nearby. Conversely, to support their numerous livestock, wealthy owners occupied significantly larger areas for their encampments and settled separately from the commoners. Such ails did not represent compact settlements. Small groups of yurts were sometimes located at considerable distances from each other, determined by economic necessity. The ethnic composition of these settlements was mostly homogeneous.

Naturally, there are no traces left of the nomadic ails of the past, and they can only be reconstructed from the descriptions of travelers and the stories of elderly aksakals, who can tell much about the past life that their grandfathers and great-grandfathers once recounted to them.

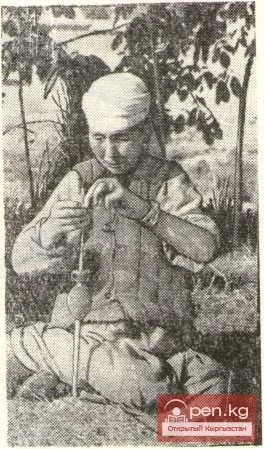

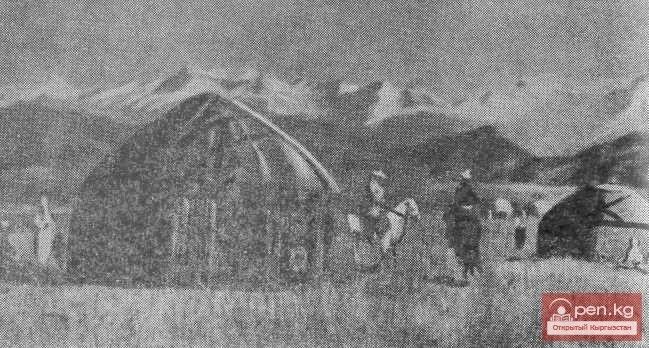

What was the surprise of researchers when, during an examination of the At-Bashinsky district in 1983, in the Bosogo area, on an early August morning, they were presented with a Kyrgyz ail of past centuries, just as it was depicted in book descriptions. More than thirty white yurts were arranged on a patch of intermountain plateau. In some places, the embers of burnt yurts still smoldered, and people in archaic traditional Kalmyk and Kyrgyz costumes walked peacefully around. On the hillside, girls and boys joyfully swung on Kyrgyz swings, and horsemen galloped by. A Bukhara merchant passed by with dignity in a turban and a white robe, belted with a rich sash.

As the reader may have guessed, the researchers stumbled upon the filming of the historical-epic film "Descendant of the White Leopard" by the famous Kyrgyz director T. Okeeva. The film is based on Kyrgyz folk legends. It tells the story of the legendary Kyrgyz hunter Kozhozhash, and the struggle of the people for freedom against the Kalmyk conquerors. The scientific consultants of the film, created based on the motives of folk Kyrgyz legends, are the well-known Soviet ethnographer and specialist in Kyrgyz national costume and traditional material culture K. I. Antipina and the expert on antiquities, archaeologist A. K. Abetekov. Through the combined efforts of filmmakers and scholars, a picture of the life of the Kyrgyz people in the past was recreated.

The issues raised in the film cannot leave the viewer indifferent. The encounter with the past forces us to deeply reflect on the pressing problems of modernity—ecological balance, the relationship between humans and nature, and their history.

And the next day, the group witnessed a living connection between the times of history and modernity. The workers of the At-Bashinsky district in the Bosogo area were solemnly celebrating the shepherd's day. The celebration included artists who spoke about the filming of the film. It concluded on a stage with decorations, where archery at jambs—silver ingots—was taking place, wrestlers competed in strength, and horsemen in agility, and competitions in horse wrestling, baiga, and ulak tartysh were held. History seemed to become today, the present reached out across the centuries to the distant past.

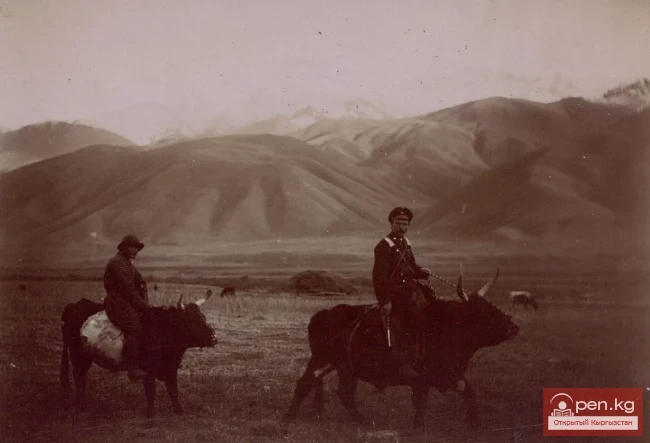

Settlement of the nomadic and semi-nomadic type of Kyrgyz in the 19th and early 20th centuries.