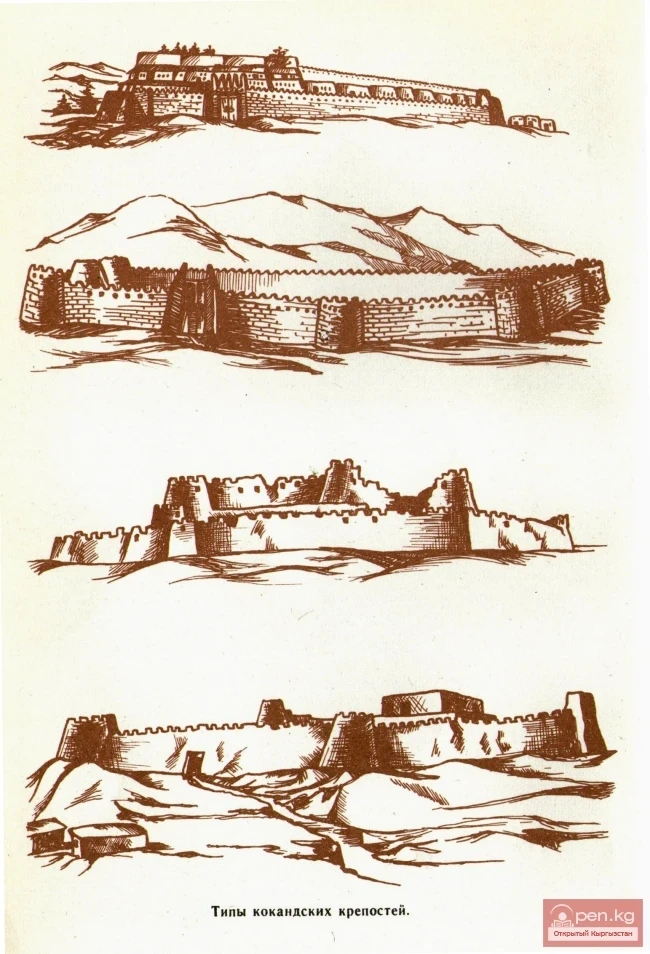

Types of Kokand Fortresses

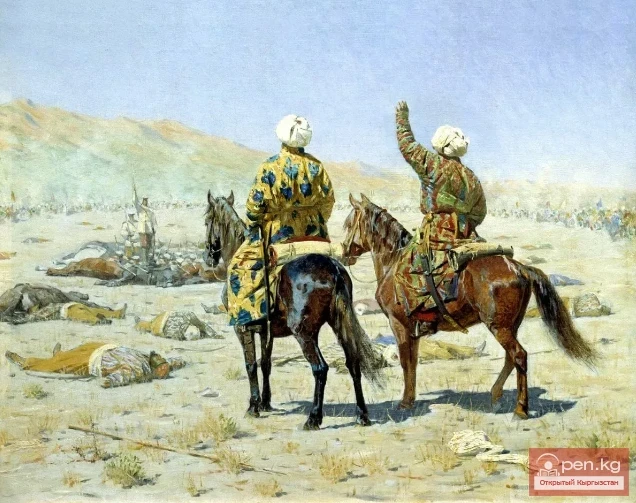

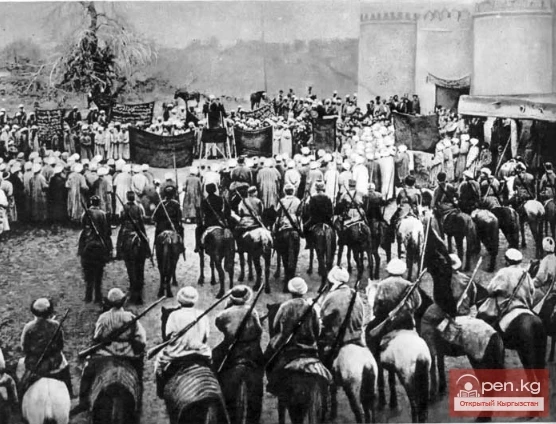

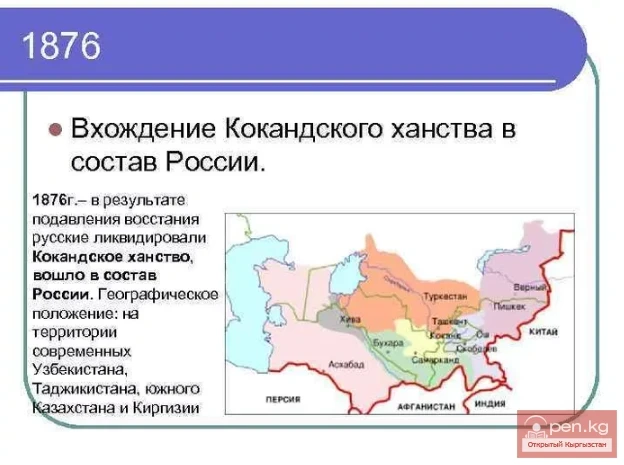

For a whole century (from the second half of the 18th century to the second half of the 19th century), the history of Kyrgyzstan was inextricably linked with the Kokand Khanate. Throughout this century, the Kyrgyz people tirelessly fought, first against the conquering campaigns of the Kokand khans, and then against the khanate-feudal oppression. Their persistent struggle contributed to the fall of the khan's despotism. However, the path to this was long and difficult. The southern regions of Kyrgyzstan were conquered by Kokand troops during the stubborn resistance of the Kyrgyz people from 1762 to 1821, while the northern regions were conquered from 1825 to 1832. The conquest policy of the Kokand was facilitated by inter-feudal clan strife.

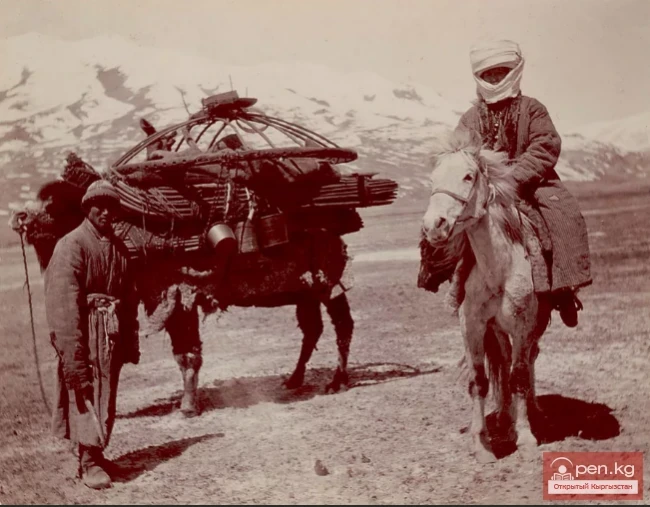

Background. The Kokand ruler Irdena, using the looting of one of the Kokand merchant caravans trading with Eastern Turkestan by the feudal lords of the Adygine tribe as a pretext for attacking the Kyrgyz, unexpectedly attacked Osh and Uzgen in 1762 and captured the Mady Fortress in battle. The united forces of the Ichkilik, Adygine, and Mongoldor tribes, led by Hadji-bi, could not withstand the onslaught and retreated into the mountains. To consolidate his dominance, Irdena left not only his governor with a troop of soldiers in Osh but also sent 50 Kokand colonists there to organize rice plantations. This marked the beginning not only of the Kokand conquest of Kyrgyzstan but also of the colonial consolidation of the fertile valley lands of the Kyrgyz, who were partially pushed into the foothills of the Fergana Range, the Alai, and the Pamirs. Gradually, the tentacles of the Kokand troops reached here as well.

But there, the Kokand already came into direct contact with the new Chinese imperial governorship — Xinjiang, with Qing border detachments and posts. To define their possessions and secure the conquered Kyrgyz lands, the Kokand began to erect fortified adobe structures. Thus, the fortresses of Tash-Kurgan in the Pamirs, Sufi-Kurgan, and Daraut-Kurgan in the Alai were established.

In 1821, Khan Omar completed the conquest of Southern Kyrgyzstan by sending his commander Seyid-Kul-bek on a winter campaign to Ketmen-Tube. The resistance of the Kyrgyz led by a certain Satyk had no success. To establish his dominance here on the Uzun-Ashat River, at the confluence with the Naryn, a fortress of the same name was erected, known among the Kyrgyz as Ulugh-Korgon.

In 1825, Kokand troops conquered the Chui Valley and erected their easternmost fortresses, Pishpek and Tokmak, where they left military garrisons. A Kokand embassy was sent to Issyk-Kul with an offer to accept Kokand's vassalage. However, the plans for the peaceful annexation of the Issyk-Kul Kyrgyz fell through. The Bugyns expressed their desire for unity with Russia. Then the Kokand khans decided to act with force: in the spring of 1831, they sent troops through the Tian Shan to the southern shore of Issyk-Kul, led by Minbashi Khak-Kuly, and from Tashkent, Lyashker-kushbegi marched with troops to Issyk-Kul. After defeating the resistance of the united forces of the Sayaks and Cheriks led by the brothers Taylak and Atantay in Tian Shan, Khak-Kuly founded three fortresses — Toguz-Toroo, Dzhumgal, and Kurtka, while Lyashker-kushbegi established Karakol, Barskaun, and others on Issyk-Kul.

The chain of fortresses erected in the center of Kyrgyz nomadism, as well as on the border with China, on the one hand, consolidated Kokand's dominance in Kyrgyzstan, and on the other hand, reflected the predatory raids of Qing troops. A quarter of a century later, Chokan Valikhanov wrote about these fortresses: “The Kokandis, having subdued the wild Kyrgyz, encircled the borders of Eastern Turkestan all the way to Hotan.”

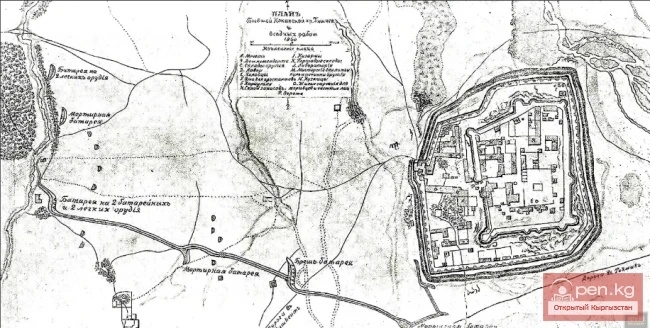

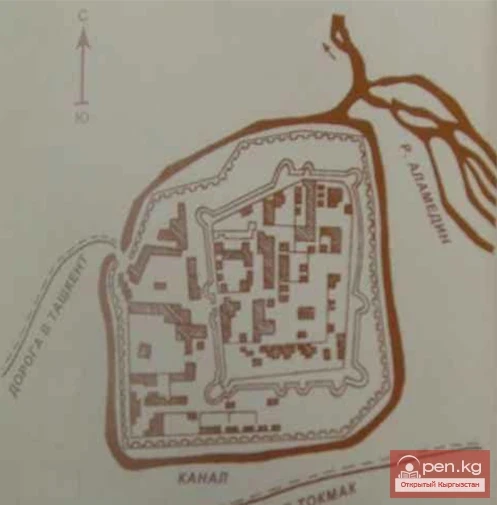

In the "Description of the Kokand Military Line on the Chu River," compiled by the senior adjutant of the separate Siberian corps, Captain of the General Staff M. I. Venyukov, plans of the Kokand fortifications Tokmak and Pishpek are provided. It states that the Kokand line of fortifications in the Pre-Chui region had a dual significance: first, it protected the border, which the Kokand considered to be the Chu River, and second, it maintained their dominance over various clans of Kyrgyz nomads migrating from Issyk-Kul to the west, mainly along the left bank of the Chu River.

This line consisted of eight fortifications: Tokmak, Pishpek, Ak-Suu, It-Kichu, Auliye-Ata, Cholok-Korgon (there was a fortress of the same name in Central Tian Shan), and Suzak. All of them were separated from the inner regions of the Kokand Khanate by low mountains (Kyzyl-Kurt, Borolday, and Kara-Tau), forming a single chain, and the first four, in addition, by the snow-covered ridge of the Kyrgyz Ala-Too. Suzak and Cholok-Korgon served as outposts on the routes to Azret and Tashkent from the lower reaches of the Chu River, while the other fortifications were located on the route from the Zailiyskiy region to Kokand.

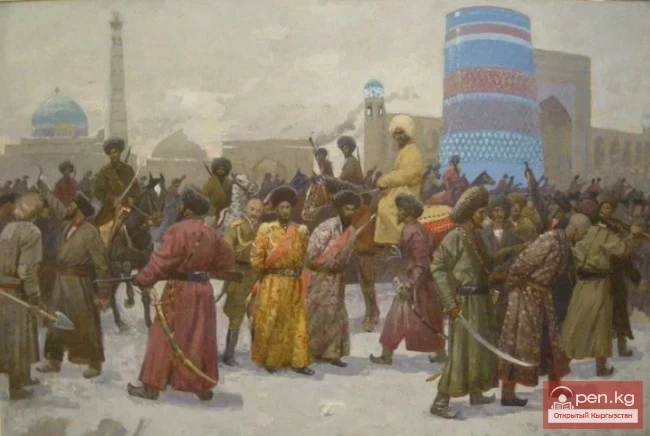

In one of the first encyclopedic articles about the Kokand Khanate, which appeared in the mid-20th century in the pages of Russian periodicals, the following characterization of the fortresses was given: “The borders of Kokand are protected by fortresses, where permanent garrisons are maintained to inspect passing caravans and to monitor the nomadic population... On the roads from Russia to Tashkent lie the fortresses: Suzak and Chulak-Kurgan; however, recently the Kokand government has arranged a new fortification ahead of them by the Chu River... Kurtka lies on the eastern slope of Belur-Tag not more than two days' journey from Kashgar.”

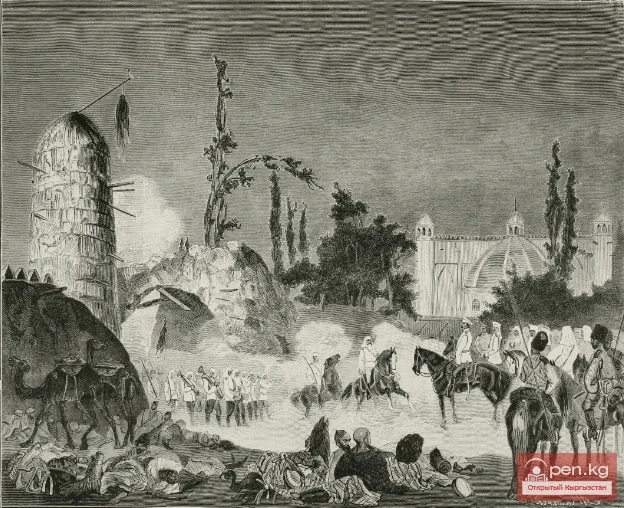

The conquest of Northern Kyrgyzstan by the Kokand lasted from 1825 to 1832, but their dominance here turned out to be short-lived. The fortresses erected, for example, on Issyk-Kul in 1832 were destroyed by rebels ten years later, in 1842, and in 1855 the Issyk-Kul Kyrgyz voluntarily joined Russia. The fortresses destroyed by the population or abandoned by the Kokand fell into decay. Even travelers in the second half of the 19th century noted that the number of fortresses was decreasing, trying to sketch and describe them.

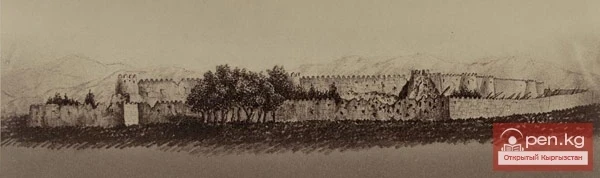

During his journey through Turkestan from 1867 to 1870, V. V. Vereshchagin left several sketches of Kokand fortresses that still retained their former outlines. Among them were “Yangi-Kurgan,” “Ruins of ancient fortress walls,” “Former fortress of Kosh-Tegeremen near the city of Khojent,” and “Watchtower in the valley of the Chu River.” To this day, they have survived in ruins, and only archaeological data, supplemented by information from archival sources, allow us to recreate their original appearance.

As early as the 1970s, the tsarist envoy to Kashgar A. N. Kuropatkin wrote that not long ago, the Kokand Khanate was the most powerful in Central Asia. Its borders extended from the city of Chimkent in the west to the Naryn region in the east, where the Kurtka fortress was built. The Kokandis controlled the entire mountainous strip up to the entrance to the Kashgar plain. Kurgashin-Kani and Tash-Kurgan were considered the border outposts of the Kokand, places for collecting zakat — taxes from nomads — and border fortifications that restrained the aggressive encroachments of Qing China.

“As long as the governments were strong,” noted Kuropatkin, “they erected a series of fortifications in the mountains, with the help of which they kept the mountain population in check. The weakening of the government's power primarily affected the mountains.

Then entire clans of Kara-Kyrgyz and Kipchaks not only usually refused to pay the established insignificant zakat from their herds but, gathering into gangs, invaded the valley and finally undermined the government that had begun to weaken.”

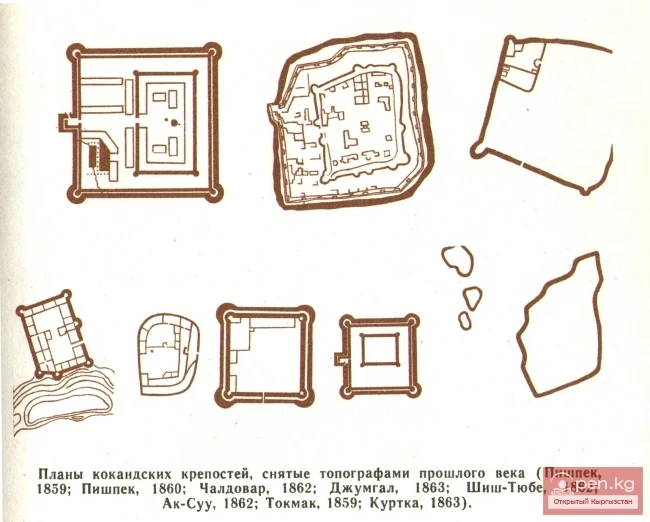

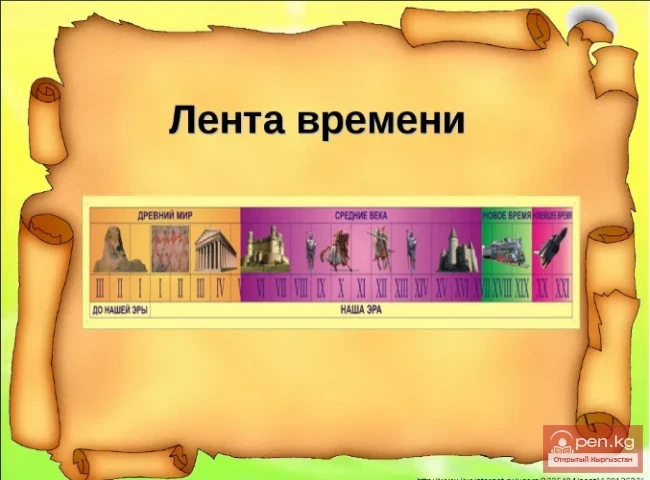

Kokand fortresses were divided into three groups by size and purpose: large, medium, and small.

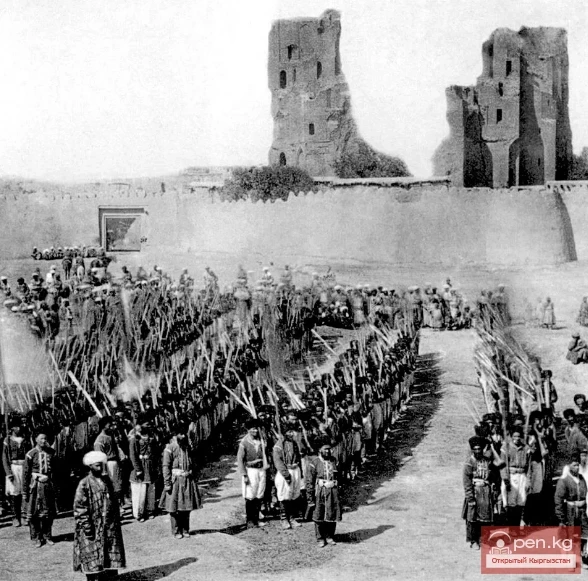

Large fortresses were usually located at strategic points and were well fortified. The size of such a fortress reached 1.5–2.5 hectares. It was surrounded by a double or even triple fortress wall and an external moat.

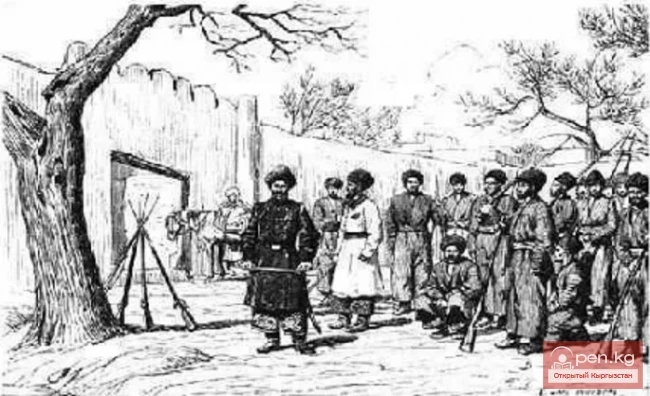

The garrison consisted of 500 to 1500 people, and the fortress was armed with several cannons.

Large fortresses can now only be reconstructed from plans and descriptions made by Russian topographers and military personnel in the last century (Venyukov, Kartusov, Varaksin, Strelnikov, Shestakov, Grechkov). These include the fortresses of Pishpek, Auliye-Ata, and Chaldovar.

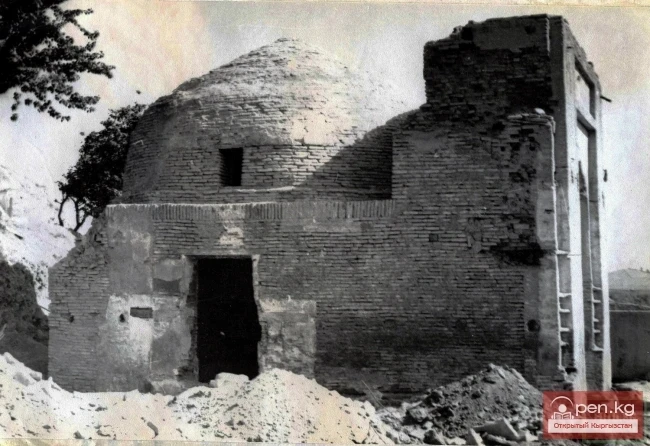

Ruins of the Citadel of Auliye-Ata

Auliye-Ata — medieval Taraz (modern Jambyl). This fortress is located on the territory of Kazakhstan; however, at one time it played an important role in the implementation of Kokand's colonial policy in Kyrgyzstan.

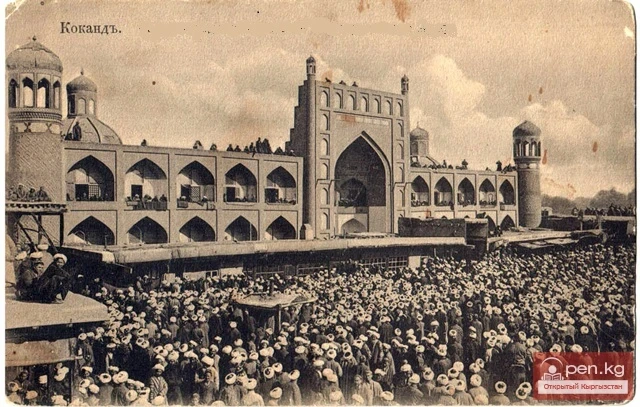

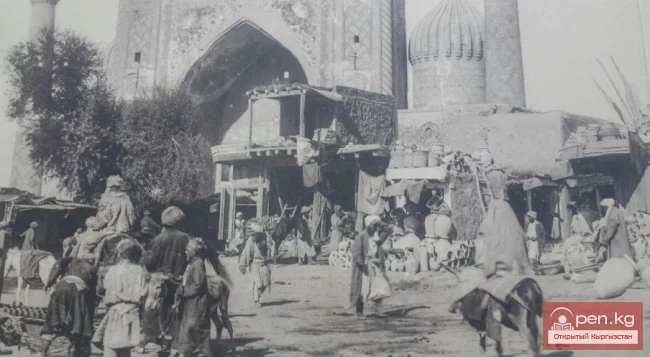

Auliye-Ata, founded in 1822, could be called a fortress-city and even an industrial center: it was one of the main Kokand fortresses in Semirechye, surpassing all other fortresses in size. It had a large market and up to 1500 residents. The fortress was surrounded by a moat and rampart, had 5 bronze cannons, and a garrison of 100 mounted soldiers and up to 500 infantry. In 1859–1860, the fortress was armed with 8 cannons and several dozen large guns that fired grapeshot. In field conditions, they were transported on camels. Located at the foot of the mountains in the Talas Valley, Auliye-Ata served as an important stronghold for the Kokand in the Chu River valley, as well as a storage facility for military and food supplies. From here, provisions and other goods were delivered to Pishpek and other nearby fortifications. It was a gathering point for all troops heading to the Syr Darya Valley to guard the upper reaches of the Chu River. Today, not even ruins remain of the large fortresses.

Much better preserved are the fortifications of medium size. Such fortresses had an area of 0.2 to 1 hectare. They were surrounded by a powerful fortress wall, flanked by towers at the corners. The height of the walls reached 5 meters. A row of loopholes ran along the top of the walls. Such fortresses usually had a garrison of about 100–200 warriors, armed with a mix of spears and cold weapons, as well as firearms. Depending on the circumstances, the garrison could be increased. The fortress was armed with several cannons. These fortresses mainly controlled nearby areas, caravan routes, served as watch posts, and their garrisons collected taxes from the population.

Currently, only three such Kokand fortresses have survived more or less well: Daraut-Kurgan in Chon-Ala, the Kan fortress on the Sokh River, and Cholok-Korgon in Central Tian Shan.

Kyrgyz Fortifications