"Kyl-kuyruk"

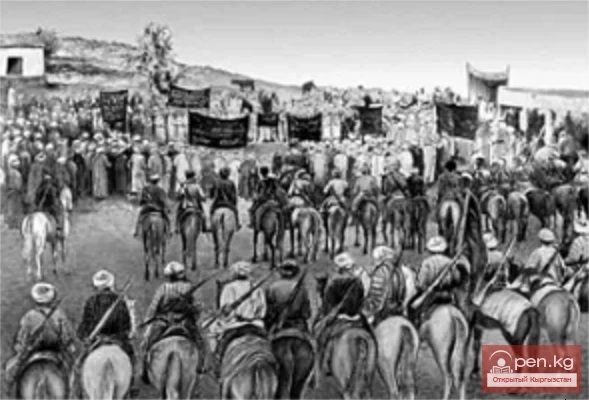

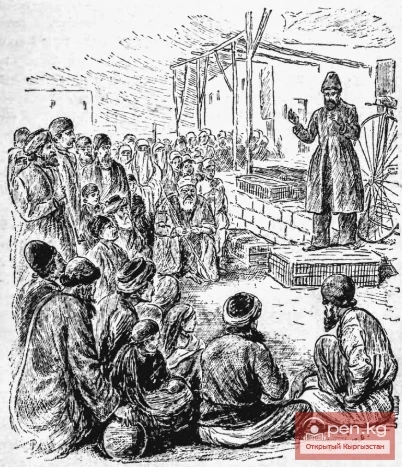

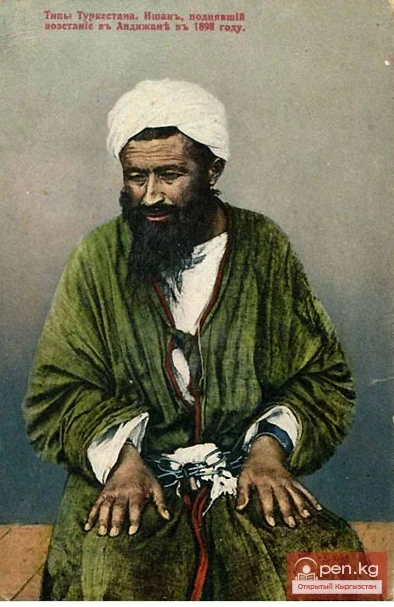

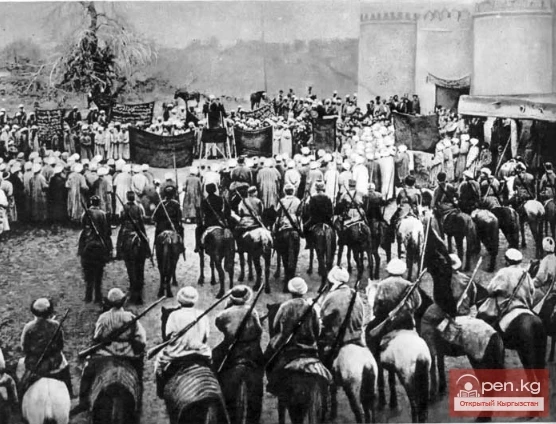

Abdurakhman Aftobachi, who had recently returned from Mecca, where he went on pilgrimage, Isa-Auliye, known for his religious fanaticism, and other representatives of the feudal nobility, in an attempt to use the workers' protests for their own interests and direct it along an anti-Russian path, declared a jihad, i.e., a holy war against the "infidels" in August 1875, at the beginning of the second stage of the uprising.

These individuals and other supporters of the uprising wrote religious appeals, calling on believers, including Kyrgyz who had accepted Russian citizenship, to participate in the jihad. However, the representatives of the feudal nobility failed to impose the slogan of jihad on the rebels and direct the popular uprising along an anti-Russian path.

The religious call did not find broad support among the participants of the uprising, who were fighting against feudal and khanist oppression and its protector—the tsarist authority. For jihad had nothing in common with the anti-feudal uprising of the working masses. However, it should not be overlooked that under these conditions, the uprising could not be free from religious connotations. During the period in question, the indigenous population practiced Islam, and therefore the rebels were believers who fought not only against feudal and khanist oppression but also against its defenders—the tsarist punitive forces, who were supported by a different faith.

The religious connotation, characteristic of many national liberation movements, was also present in the uprising of 1873—1876 during its second stage. However, it could not change the anti-feudal and national liberation character of the latter.

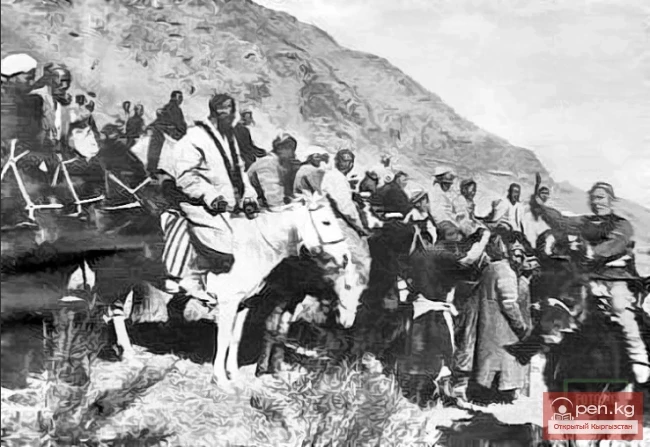

As some archival data suggest, jihad was not the only slogan of the rebels. Among the Kyrgyz and Kipchak rebels, who were less committed to the religion of Islam, the call "kyl-kuyruk," i.e., a call for the universal participation in the uprising, was popular. Here is what a Kyrgyz rebel, who was captured by the punitive forces, reported on this matter: "Among the Kyrgyz, as well as among the Kipchaks, there is a kind of jihad, or as they call it 'kyl-kuyruk' (kyl-kuyruk — K.U.), i.e., the universal participation of the entire population in the war (uprising — K.U.)." The call kyl-kuyruk found support among broad layers of the nomadic and semi-nomadic population of the khanate.

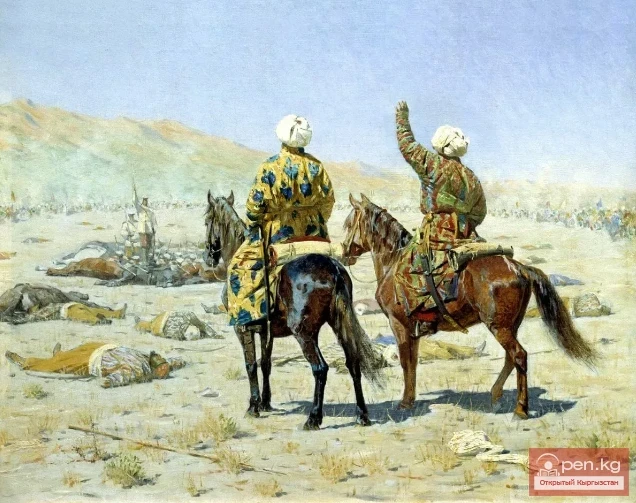

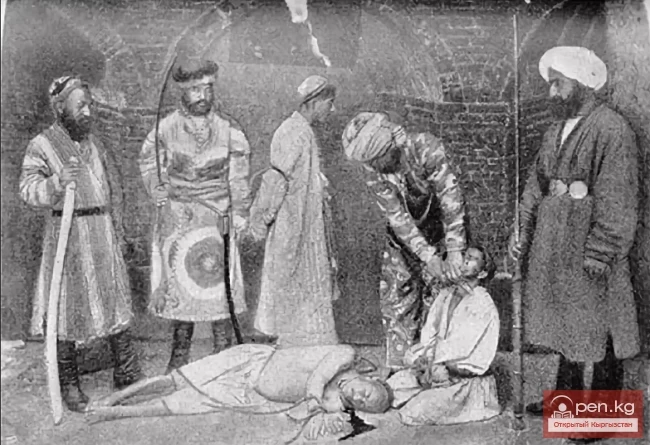

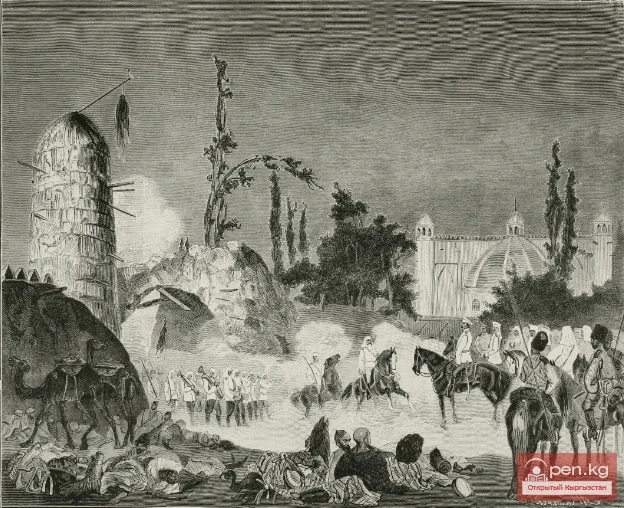

The uprising did not have an anti-Russian character in any way. On the contrary, significant layers of the rebel masses, especially Kyrgyz herders, gravitated towards Russia and adhered to a pro-Russian orientation. However, the actions of the tsarist representatives, aimed at protecting the power of Khudoyar Khan and then Nasr-Edin Khan, turned the rebels against them, whose resistance they had to suppress only by military force. These were tragic pages of history. The ruling classes of tsarist Russia were closer to the interests of the ruling elite of the Kokand Khanate than to the interests of the popular masses, who were also engulfed in "turmoil and disorder." It is hard to disagree with the opinion of some researchers that if the tsarist authority had not protected the overthrown Khans Khudoyar and Nasr-Edin, as well as the feudal lords surrounding them, there would have been no actions from the rebels directed against the Russian troops.

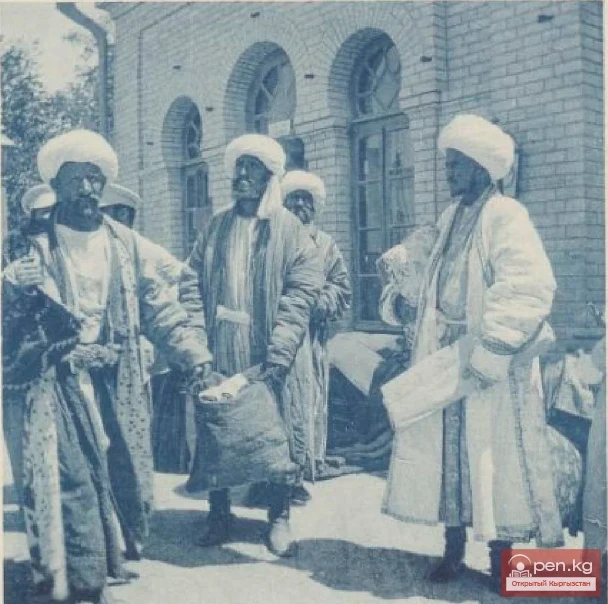

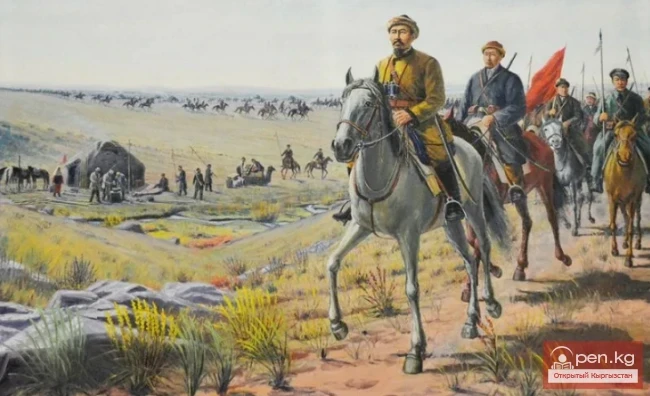

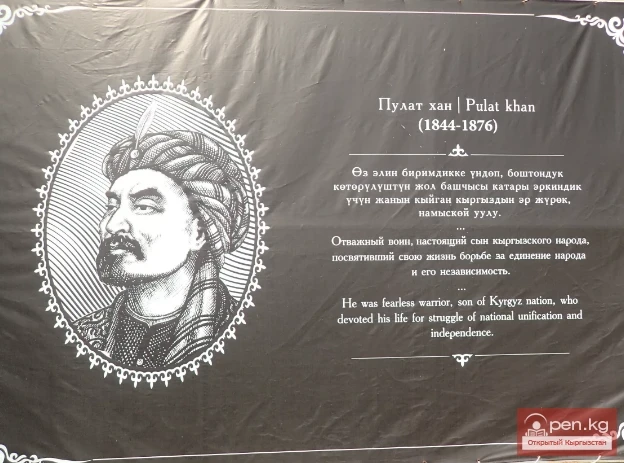

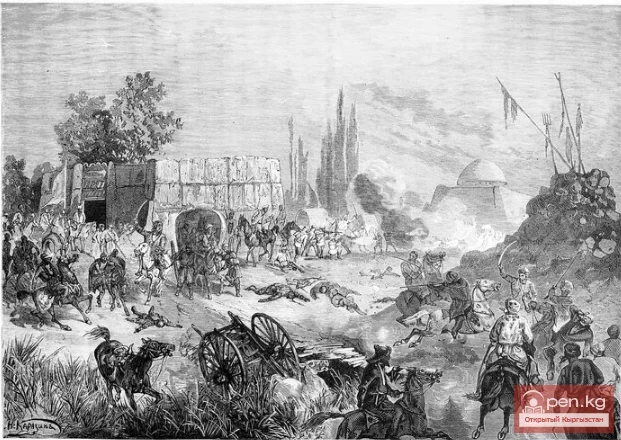

The uprising in question occurred in two stages. The first stage covered the period from early spring 1873, i.e., from the beginning of the uprising until mid-July 1875. At this stage, the main participants in the uprising were Kyrgyz nomads and semi-nomads inhabiting the southern and southeastern regions of the khanate. They were supported by Uzbek and Tajik peasants, who often actively participated in the open protests of the herders. When the rebels occupied Uzbek and Tajik kystaks and cities, the local residents usually joined the rebels and actively fought alongside them against the Kokand Khan and the feudal lords surrounding him. At this stage, the rebels, particularly the Kyrgyz masses, while fighting against the Kokand oppressors led by the Khan, sought help and support from Russia. They repeatedly appealed to the Russian authorities with letters and sent their representatives, even expressing a desire to accept Russian citizenship. However, the representatives of tsarism, supporting the power of the Kokand Khan and the feudal lords surrounding him, did not give a positive response to these requests from the rebels. At this stage, although the uprising had acquired a mass character, it did not yet have a wide scope. It was limited to the southern part of Kyrgyzstan and some areas of the Kokand Khanate itself. During this period, the uprisings were primarily led by representatives of the people. The uprising was directed exclusively against the Kokand Khan and his entourage of feudal nobility.

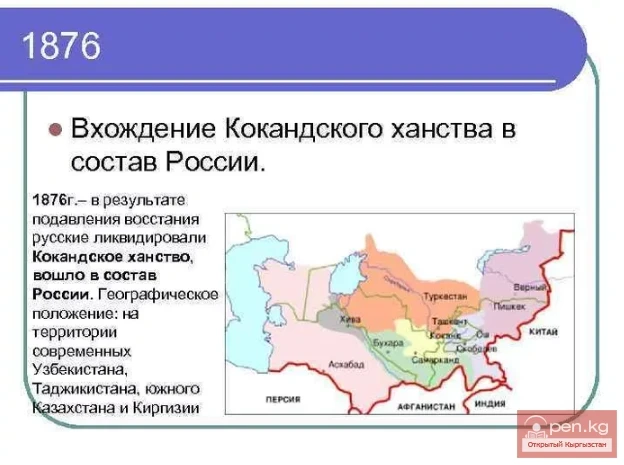

The second stage covered the second half of July 1875 to mid-February 1876, i.e., until the end of the uprising.

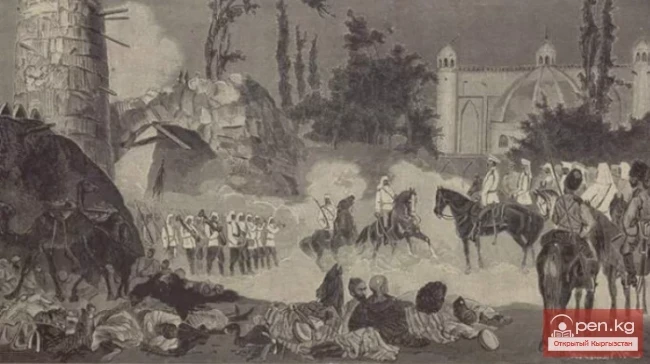

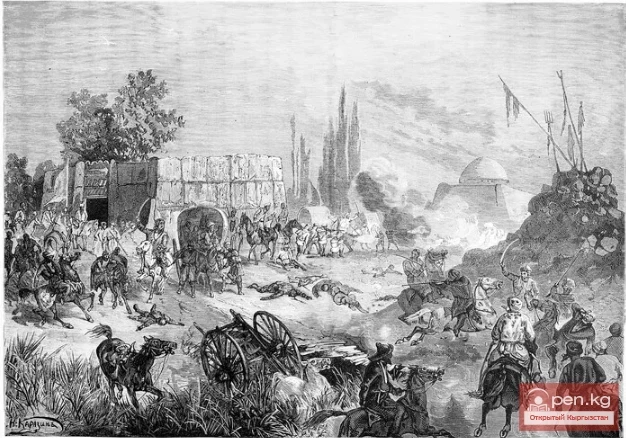

The uprising gained particularly wide scope and unprecedented mass participation. The southern part of Kyrgyzstan and the entire territory of the Kokand Khanate, including some areas and cities that had recently joined Russia, were involved in it. Broad layers of the indigenous population of the Kokand Khanate and the peoples under its control actively participated in it. At this stage, the uprising transformed into a joint uprising of Uzbek, Kyrgyz, and Tajik workers against feudal and khanist oppression and its protector and defender—tsarism.

The uprising, while not losing its anti-feudal essence, acquired an anti-colonial character. Its focus gradually shifted against the tsarist authority, which, guided by its colonial interests, openly protected the overthrown Kokand Khans and sent troops to suppress the uprising. In the second stage, particularly starting from August, the uprising to some extent acquired a religious connotation, which, however, could not influence the character of the uprising or direct it along an anti-Russian path. At this stage, a number of representatives of the feudal nobility, pursuing their personal interests, joined the uprising. Some of them managed to infiltrate the leadership of the uprising. However, they failed to use the workers' protests for their selfish interests, giving it a reactionary character.

Joint Uprising of Uzbeks, Kyrgyz, Tajiks, and Karakalpaks in the Uprising of 1873—1876.