The Struggle of the Kyrgyz Against the Conquerors. Tylek Batyr

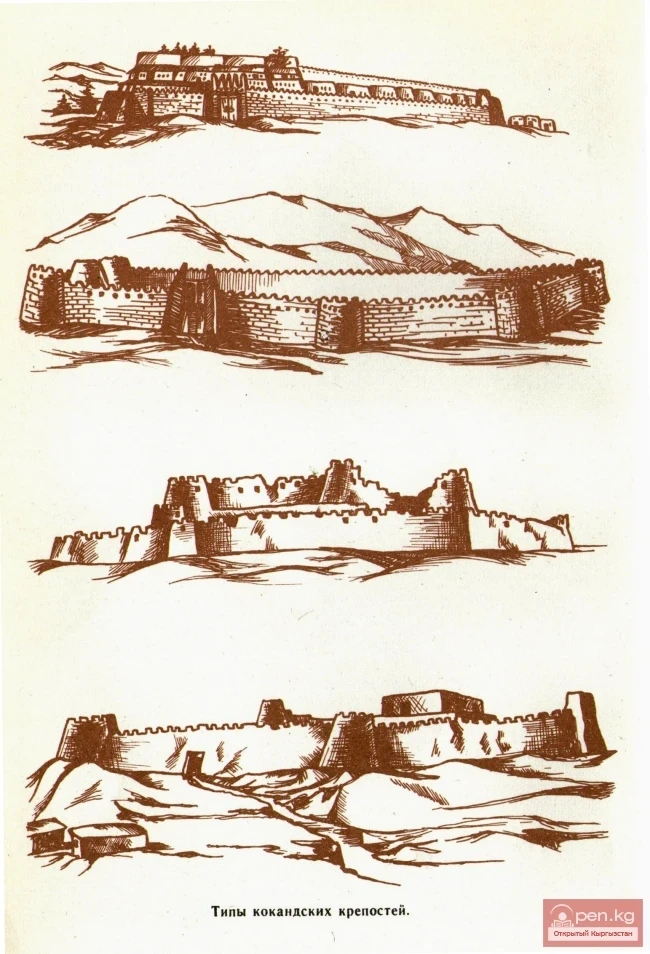

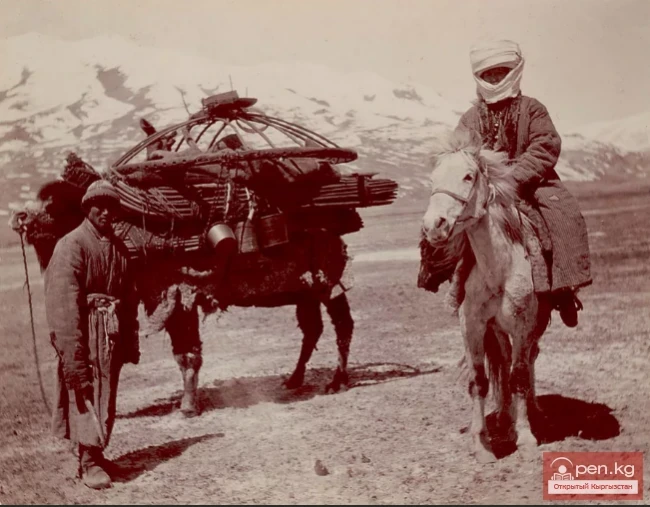

The Kokand Domination in Kyrgyzstan. In the early 1830s, the Kokand Khanate urgently began constructing fortress fortifications to maintain a constant military presence. This was extremely necessary for strengthening its rear and conquering the northern regions of Kyrgyzstan. In 1830, the Jumgal fortress was built. In 1831-1832, the Kurtka fortress was erected in Naryn. The tribes of Central Tian Shan—Sajaks, Basiz, Cheriks, Moguls, and Bugus—who sided with the Kokand against the Chinese expansion did not offer armed resistance to the entering Kokand troops. Moreover, the people of Tylak Batyr helped them build fortifications. The ruling circles of Kokand skillfully exploited the sentiments of linguistic and religious community with the Kyrgyz. Indeed, the local population perceived the Kokand as "their own" compared to Qing China.

After building the fortresses and placing detachments of 300-500 infantry and cavalry warriors there, the Kokand appointed a bek-governor. A local administrator—a datka—was chosen from among the Kyrgyz feudal lords, who collected taxes for them. Every two years, the amount of taxes and dues increased. Such oppressive orders severely affected the lives of free nomads. Year by year, their exploitation intensified, and the people fell into poverty.

The violence of the Kokand manifested not only in the collection of unbearable taxes from the population. In 1832, the Kokand governor began to seize beautiful girls and young men in Naryn, At-Bashi, Ak-Tala, and Toguz-Toro. According to him, the young men were to be taught how to care for livestock, military skills, etc. Three flocks of sheep, 30 camels, and 200 horses were driven to the Kurtka fortress. To calm the parents and relatives, a rumor was spread that the training would take place in the fortress mosque. But in the fall of 1832, it became known that the girls and young men, along with the collected livestock and jewelry, were being sent under guard to Kokand. This news quickly spread through the ails. The cup of patience was overflowing...

The Feats of Tylak Batyr. Learning of the Kokand plans, Tylak Batyr said: “Indeed, the Kokand have gone too far. How can one endure such things!” Gathering forty dzhigits, Tylak Batyr set off in pursuit.

...At the descent from the mountain pass, an ambush was set up led by Chabyldai. Tylak waited for the Kokand troops with forty warriors at a fork in the road, at the turn towards Muuanak. Evening was approaching when the Kokand appeared around the bend. Ahead, serenely seated on a horse surrounded by 20 warriors was the deputy governor. Behind them trudged the girls and boys being sent to the camp as offerings. The young men had their hands tied behind their backs, and shackles on their feet. They were driving livestock. The procession was closed by 20 warriors. On both sides of the convoy, another 10 warriors guarded it.

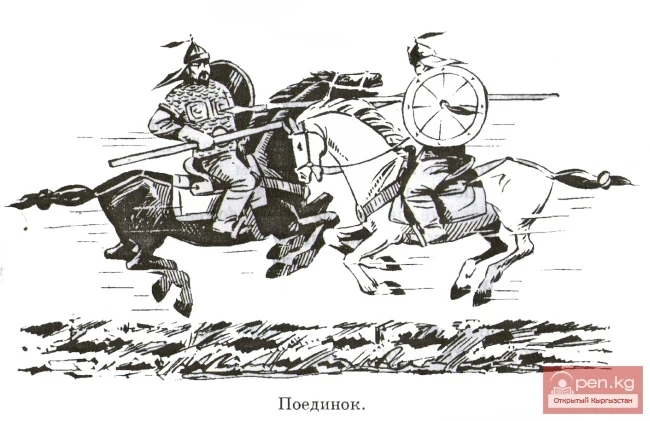

But from the red spur, Tokchoro hooted like an owl, signaling the attack. It was a convenient moment: the beginning of the lengthy convoy was on the western side of the spur, and the end was on the southeastern side; the rear guard did not hear or see what was happening ahead. With the battle cry “Tylak! Tylak!” the dzhigits spurred their horses. Tylak Batyr directed his horse straight at the deputy bek—Nazar, widely known to the inhabitants of both banks of the Naryn for his audacity and cruelty. He had many dirty deeds on his conscience—mockery, violence against the defenseless. He was simply taken aback when he saw Tylak Batyr charging at him in shining armor on a huge bay horse, fierce like a lion. “Duel!”—was all he could make out. Nazar's soul sank to his heels, but there was no way out, and he, cracking the whip on his steed, rode forward. Holding a spear in his right hand, he rushed at Tylak. A powerful blow from Tylak struck Nazar in the collarbone. The spear did not pierce the armor, but Nazar, unable to stay in the saddle, fell to the ground.

At that moment, Tylak Batyr's close friend Bebe Tai threw a noose around Nazar's neck and dragged him along.

The fight with the guards that followed the duel between Tylak and Nazar lasted no more than half an hour. A dozen Kokand warriors were seriously wounded, eight received minor injuries, and the rest were tied up. There were also wounded among Tylak's entourage. The boys and girls were freed, given horses, supplied with food for three days, and sent back to their native ails. The weapons and livestock were divided among Tylak's dzhigits. A vow was taken from the Kokand sipays that they would not return. The deputy bek and the remaining "army" were driven out of Toguz-Toro. A messenger was sent to Madali Khan, the ruler of the Kokand Khanate, with a message that if he dared to send troops to Kurtka again, no one in the fortress would guarantee the life of the khan's deputy and his warriors. A warning followed: “We will wait for the messenger in Uzgen for three days. If there is no response or if the messenger gets into trouble, we will level Kurtka to the ground...”

Enraged, Madali Khan ordered both Nazar and the messenger to be hanged and commanded the troops to march. This was reported to Tylak Batyr by trusted people from Kokand.

To suppress the uprising, the khan sent a force of 500 men to Ak-Tala led by Arab Batyr. The battle took place on the Bychan plain in Toguz-Toro. The Kokand suffered defeat, with 400 of their warriors lying on the battlefield. The commander and the remnants of his entourage fled. Tylak caught up with them and challenged Arab to a duel, in which he killed his opponent with a spear. Realizing that Tylak could not be defeated in open battle, the Kokand decided to take him by trickery.

The Death of Tylak Batyr. Summer of 1838. Tylak Batyr was feeling unwell. He had a headache. In fact, this year he often had headaches. His mood was gloomy, he felt dizzy, and wanted to lie down. There was no benefit from the invited tabibs (doctors). One of the dzhigits, having heard that there was an old healer in one of the neighboring villages, sent for his son...

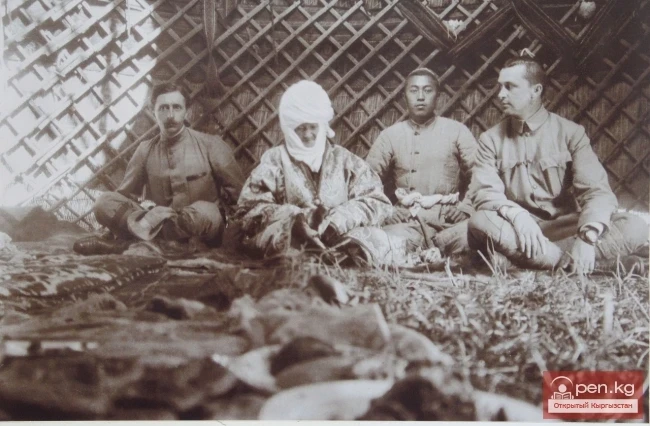

The healer turned out to be a man of about fifty, in a neat white turban, dressed like an Andijan. He held Batyr's hand, saying each time: “Inshallah” (“if Allah wills”), then poured a potion from his flask into a spoon and gave it to Batyr to drink. After a while, Tylak opened his eyes and felt better. Raising his head, he gave orders to his wives. He called his son Osmon and seated him beside him. Then he stood up, performed a prayer, and lay down again. The old man whispered some incantation and addressed Tylak: “Batyr, allow me to let blood from your head.” Tylak shook his head. “Then at least allow me to shave it,” suggested the old man. The Batyr did not respond. The healer washed Batyr's head with warm water and soap, took out a knife, and in an instant shaved him. He applied medicine to the two cuts. After some time, the old man went out to the guest room. The sun had already set. Batyr was tossing from side to side, enduring the pain, then said: “Call the old man.” The dzhigit sitting at his feet immediately jumped up and ran for the healer, but he was nowhere to be found. He ran out into the yard. One horse was missing from the hitching post, while the old man's donkey stood quietly aside. Everything became clear. With a shout, the dzhigit rushed into the street, but heard faint moans. He peeked behind the partition where kitchen utensils were stored and saw a woman lying in blood, who had been serving the guest. “Catch the old man!”—he ordered the dzhigits who had come running at his shout, and hurried to the yurt where Tylak Batyr lay. Osmon was sitting as if nothing had happened beside his father, while his wife was busy with her own affairs. The Batyr was dead...

Tylak's blue banner was hung on the left side of the yurt of the senior wife—baybiche, the huge yurt was covered with black felt, two steeds—a bay trotter and a black horse were saddled, covered with a black blanket. Forty dzhigits, nine sons lined up in a row, bracing their sides with their arms, mourned the Batyr. The three widows of the Batyr echoed them in voice. And the sorrowful news spread to different corners of the Kyrgyz land.

Read also:

Fortress Jumgal

Jumgal Fortress is located in the Jumgal district in the middle reaches of the Jumgal River, on...

The Uprising Led by Brothers Taylak and Atantay

The Uprising of 1832 in Central Tian Shan. The choro clan from the Sayak tribe, who were nomadic...

Taylak Batyr and Atantay-Biy

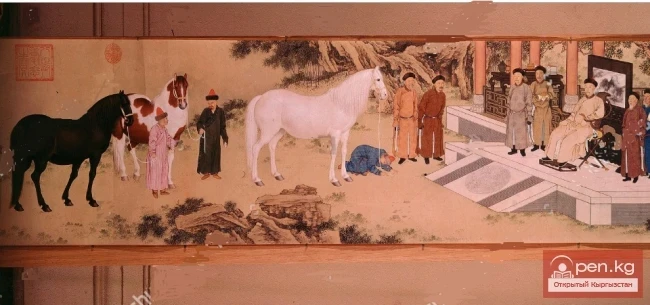

Brief information about Taylak has been preserved in Chinese chronicles of the 19th century, and...

Kokand and Kyrgyz Fortifications

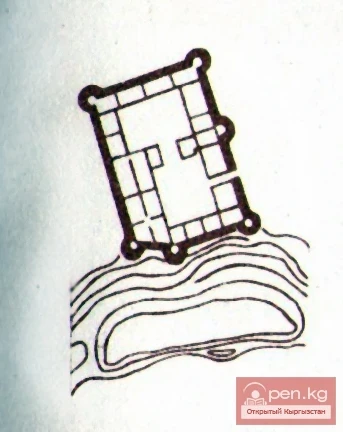

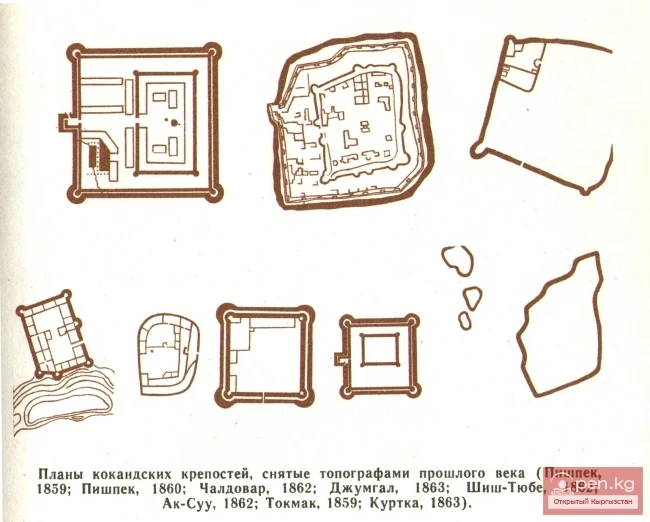

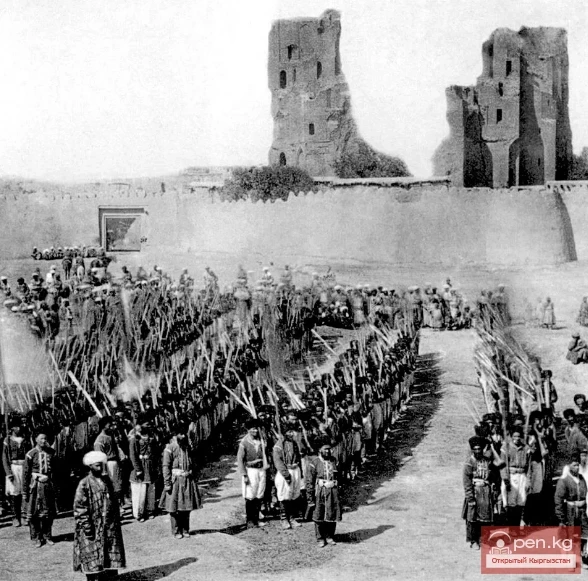

Types of Kokand Fortresses For a whole century (from the second half of the 18th century to the...

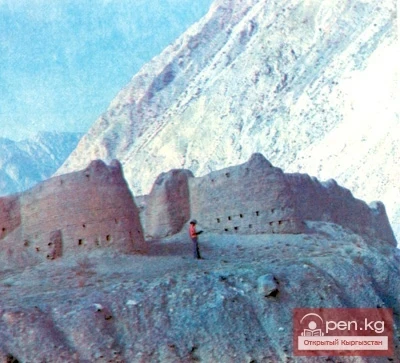

Fortress Kurtka

There is particularly much information in the literature about the Kokand Fortress Kurtka, which...

From the Kokand Fortress to the City of Frunze. The Kokand Fortress

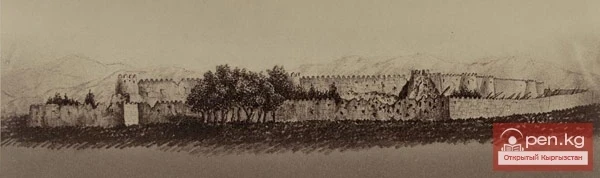

FROM THE KOKAND FORTRESS TO THE CITY OF FRUNZE KOKAND FORTRESS In the second quarter of the 19th...

The Fortress of Pishpek

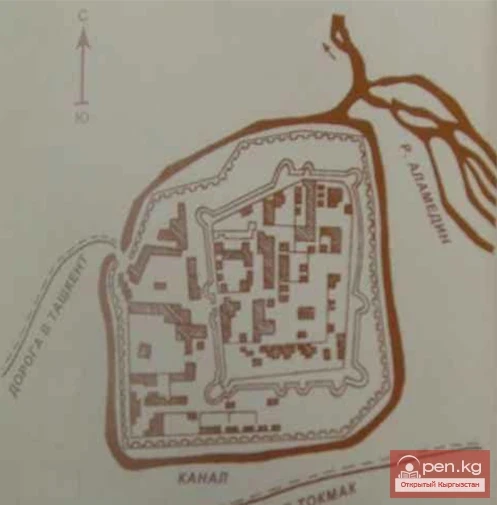

According to Russian sources, the fortress was built in the eponymous area in 1825 by the Kokand...

Tokmok has been the administrative center of the Chui Valley since 1825.

Kokand Fortress in Pishpek The natural and climatic conditions, along with the diverse riches of...

Uprisings of the Kyrgyz from 1845 to 1848 Against the Kokand Khanate

Uprisings of the Kyrgyz against the Kokand Khanate The internecine feudal struggle between the...

The Fortress of Daraut-Kurgan

Daraut-Kurgan Fortress is located in the village of the same name on the left bank of the...

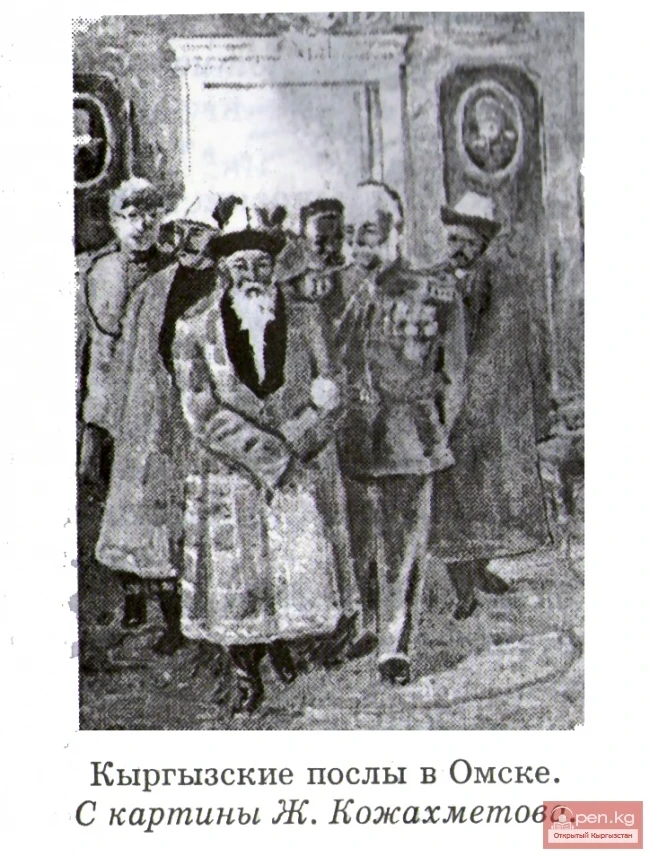

The Joining of Northern Kyrgyzstan to Russia

The Creation of an Independent Kyrgyz Khanate and Its Collapse. In the mid-19th century, the...

The Fortress of Kan

In the middle reaches, the Sokh River receives the tributary Abghol (a river from the lake), at...

Kyrgyz Fortifications

Kyrgyz Fortresses Archaeological studies of the Kokand fortresses and archival sources now allow...

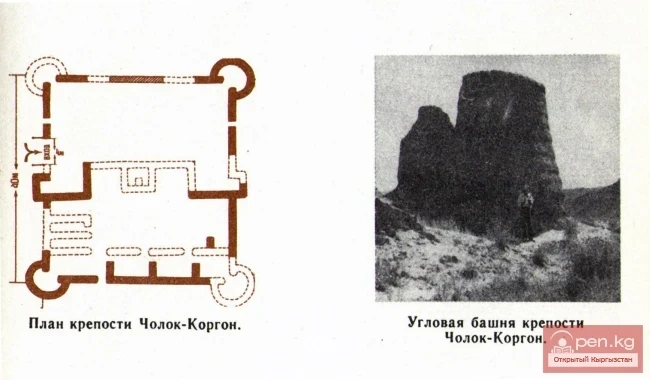

The title translates to "Cholok-Korgon Fortress."

Cholok-Korgon Fortress is located two and a half kilometers northeast of the village of Konorchok...

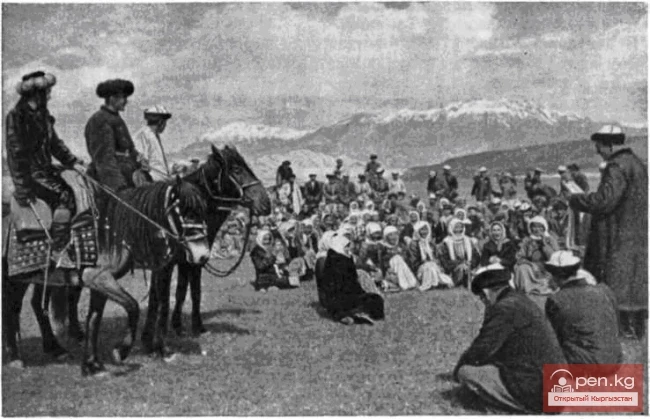

Kyrgyz in the Russian Empire

The Conquest of the Kyrgyz by Russia. In the last quarter of the 18th century, the southern tribes...

Chuy Kyrgyz Against Excessive Taxes from the Kokand Khanate

Uprisings of the Kyrgyz in 1850 - 1857. In the summer of 1850, part of the Chuy Kyrgyz, rising up...

Kyrgyz as Creators of the Kokand Khanate

Kyrgyz of Fergana Together with Uzbeks Created the Kokand Khanate Every person, no matter how...

Parables about Heroes

Mother's Milk It was a long time ago, during the time of the Kyrgyz war with the Dzungars....

The Territory of the Kyrgyz in the 18th to Early 20th Century

During the period under consideration, the Kyrgyz population occupied approximately the same part...

May Uprising of 1858 in the Southern Regions of Kyrgyzstan

The Uprising in May 1858 in Southern Kyrgyzstan. It took on a relatively large scale,...

Kyrgyz Under the Rule of the Kokand Khanate

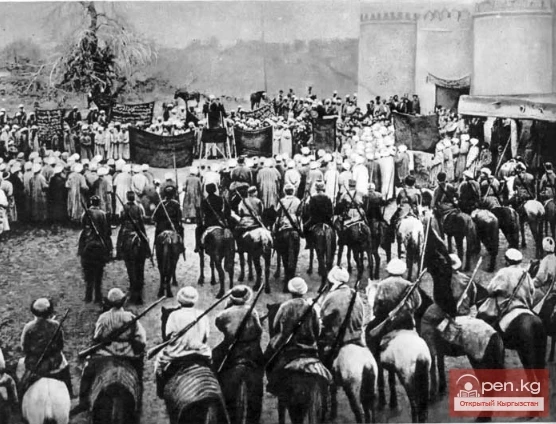

Foundation of the Khanate and its Strengthening. In the early 18th century, a new feudal state was...

Tokmok

Tokmok (Kyrgyz: Токмок) is a city in Kyrgyzstan, the administrative center of the Chuy Region. It...

The Bukhara Invasion of Fergana in the Early 1840s

The Bukhara Invasion of Fergana The successful conquest of Kyrgyzstan's territory by the...

The People of Central Asia Against the Domination of the Kokand Khanate

The Uprising of Ordinary Kazakhs and Kyrgyz Inhabitants of the Talas Valley Against the Dominance...

The Minimal Influence of the Kokand Khanate on the Economic Life of the Kyrgyz

The Influence of Kokand Colonization on the Kyrgyz The Kokandis encouraged the Kyrgyz to settle in...

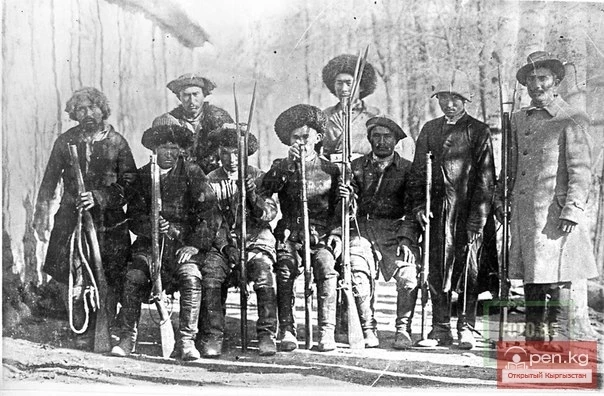

Military Forces of the Kyrgyz in the 18th - Early 20th Century

Since the Kyrgyz did not have their own state formation during the period in question, there is no...

The Emergence of Bishkek

THE ORIGIN AND DEVELOPMENT OF BISHKEK Findings of stone tools by archaeologists during the...

The Siege of the Pishpek Fortress

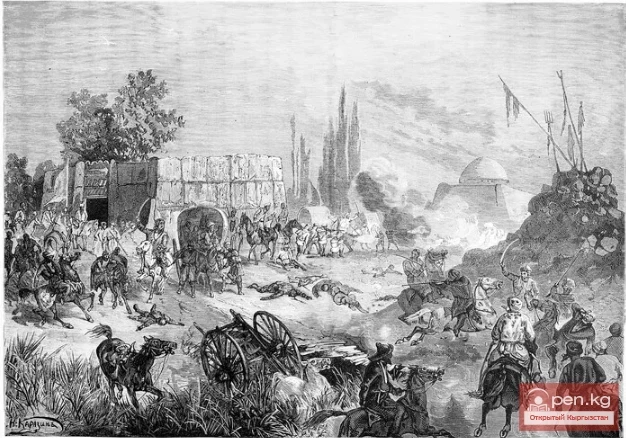

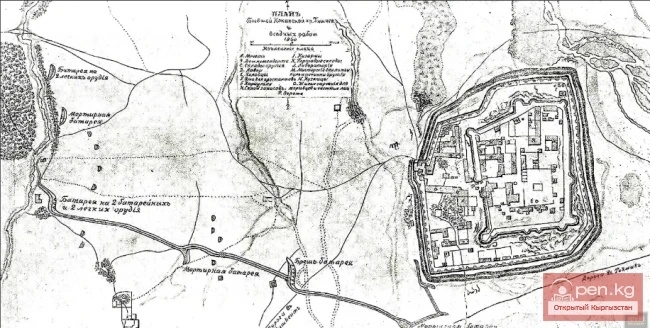

Plan of the siege of the fortress of Pishpek by Russian troops The Capture of Pishpek In October...

Foreign Policy of the Kyrgyz in the 18th - Early 20th Century

During the period in question, Kyrgyzstan was unable to conduct any foreign policy. However,...

Muhammad Kyrgyz

The situation in Central Asia. In the early 16th century, feudal fragmentation intensified not...

The Joining of the Kyrgyz to Kokand in the Late 18th Century.

The Performance of Kyrgyz Tribes Against the Conquest Policy of Irdana. In the Sagymbaev version...

Events of the Second Half of the 18th Century in Southern Kyrgyzstan

Events 200 Years Ago Let’s return to the events of 200 years ago. What was Osh primarily for the...

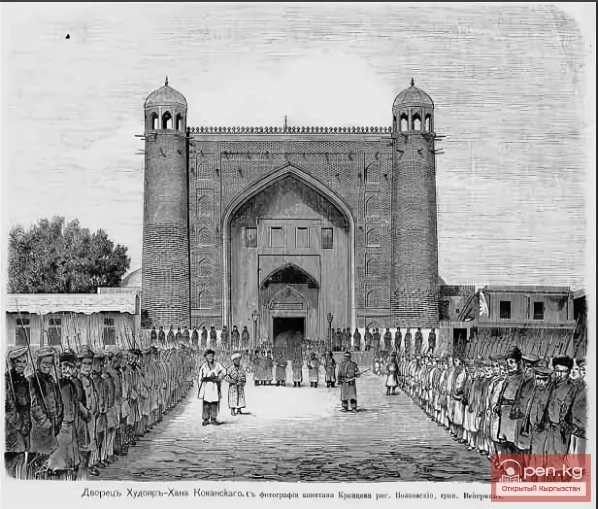

The Reign of Khudoyar Khan

REVOLT THAT ESCALATED INTO A PEOPLE'S WAR After the defeat in the 1845 uprising, the Kyrgyz...

Kokand Fortress of Pishpek

PREHISTORY OF THE CAPITAL OF KYRGYZSTAN For those who currently live in this beautiful city,...

Document No. 3. The Revival of Pishpek

CAPTURE OF THE PISHPEK FORTRESS BY THE IMPERIAL TROOPS AND THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE PISHPEK...

Politics in Eastern Turkestan in the Late 50s-60s of the 18th Century.

The Defiance and Bravery of the Kyrgyz The ambitions of the Qing dynasty and their aggressive...

Popular Uprisings Involving Kyrgyz People

CLUSTERS OF WRATH For a researcher, it is not easy to classify the protests against the...

Punitive Operations of Khudoyar Khan Against the Rebels in 1873

The Spring Uprising of 1873 Against Kokand The uprising began in the spring of 1873. Its catalyst...

Traces of Political Activity of the Kyrgyz in the Second Half of the 18th Century.

The Power of the Kyrgyz in the Mid-18th Century Traces of the political activity of the Kyrgyz in...

Kyrgyz Feudal Lords in Search of Allies

Multi-Step Politics of Kyrgyz Tribes in the Late 18th Century In the late 18th century, Kyrgyz...

Governance in Kyrgyzstan in the 18th to early 20th Century

The new period of Kyrgyzstan's history spans from the 18th to the early 20th century. It can...

Historical Preconditions for the Convergence of the Kyrgyz with Russia

Until the mid-19th century, the Kyrgyz people were under the rule of the Kokand Khanate. The...

The Performances of the Kyrgyz in the First Half of the 1860s

National Liberation Movement Against the Kokand Khanate On June 1, 1868, a clash occurred between...

The Struggle of the Workers Against the Kokand Khans and Their Patron — the Tsarist Authority in 1875-1876.

The Struggle of the Working People Against the Khans of Kokand and the Tsarist Authority. In the...

The Population of Kyrgyzstan in the 18th - Early 20th Century

Historical information about the size of the multi-ethnic population of the Fergana Valley during...

Kyrgyz-Kokand Relations in the 18th Century

The Important Political Role of the Kyrgyz in Fergana at the End of the 18th Century With the...

Ambitions and the Finale of Pulat Khan - the "Alai Prince"

Who was this impostor, hiding behind what seemed to be a noble cause under the name of the heir to...

Signing of the Trade Agreement between Khudoyar Khan and Governor-General von Kaufman

Orientation of the Uprising Kyrgyz Workers Towards Russia The Kyrgyz workers, fighting against the...