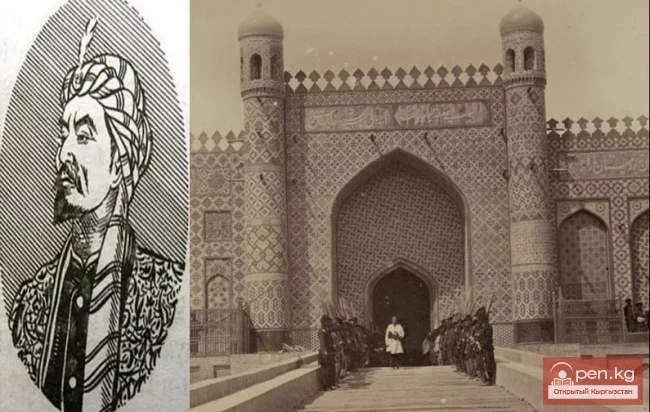

Who was this impostor, hiding behind what seemed to be a noble cause under the name of the heir to the Kokand throne?

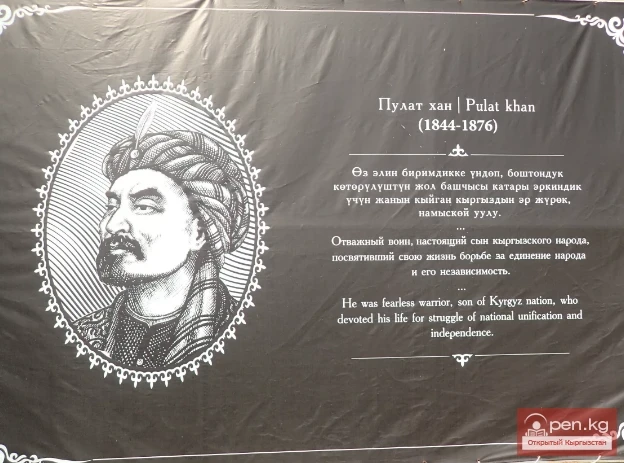

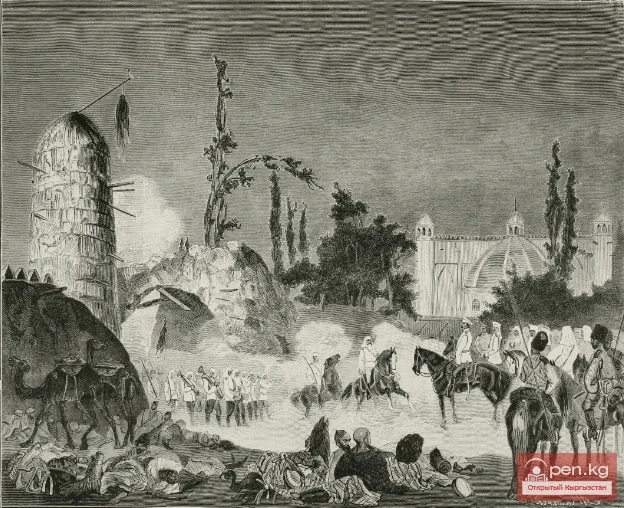

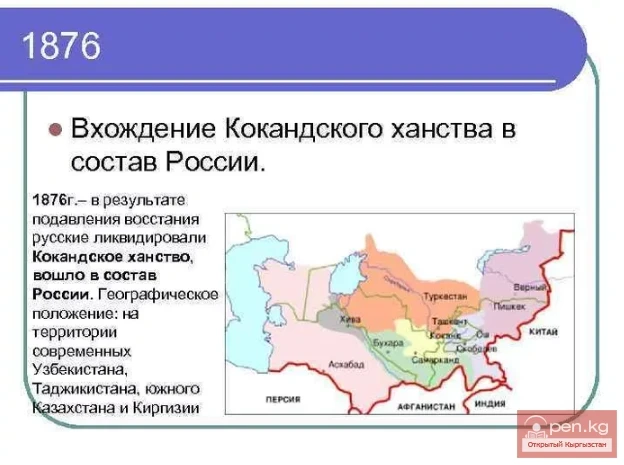

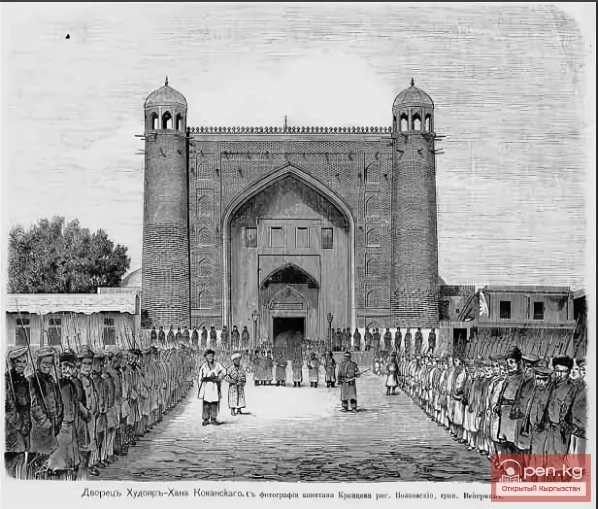

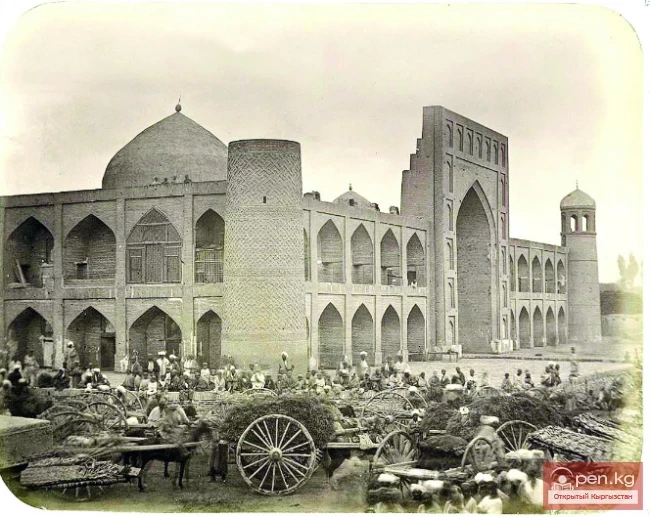

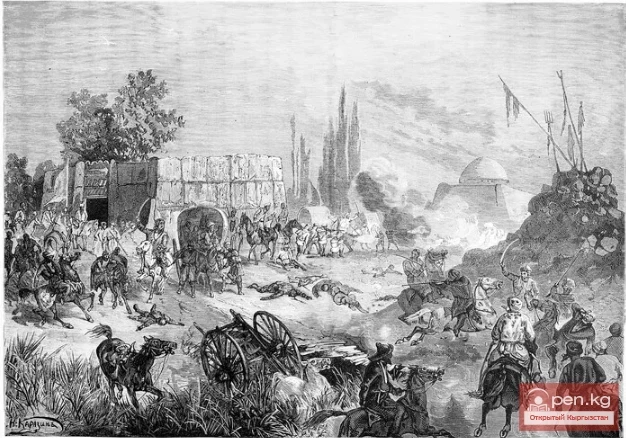

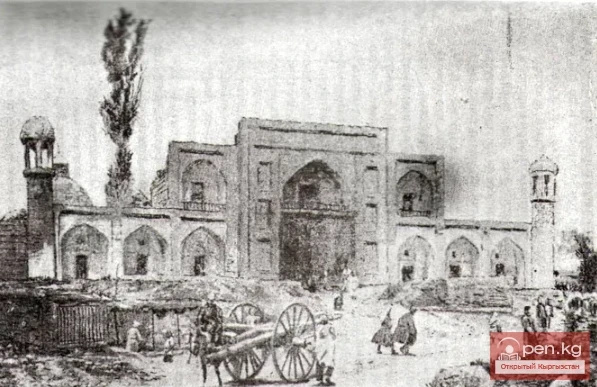

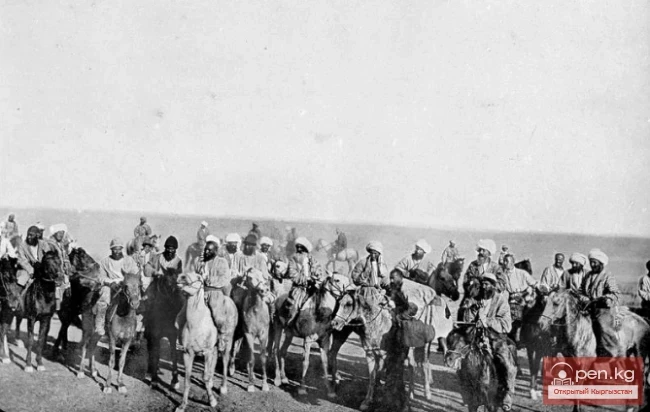

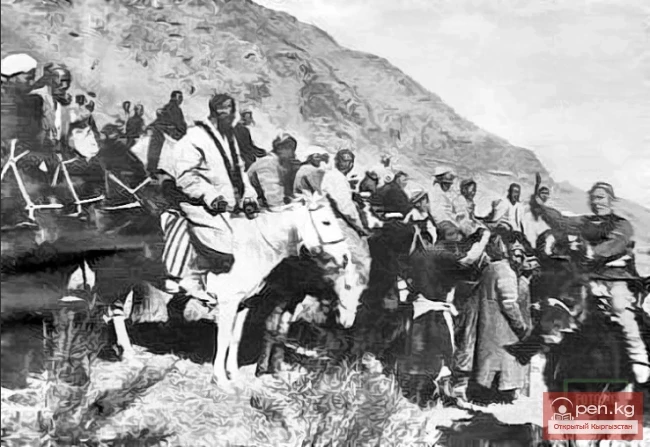

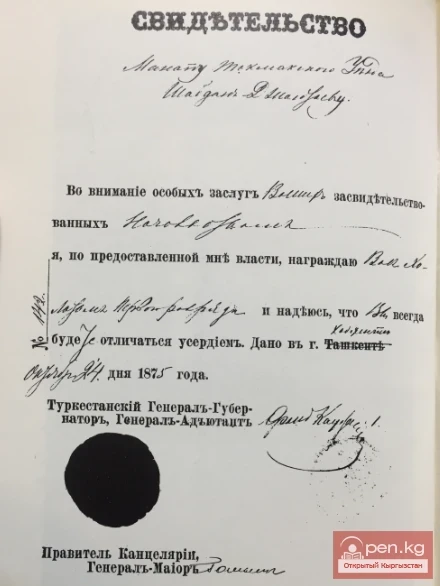

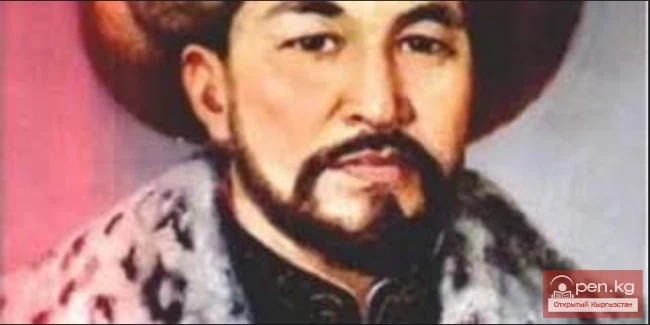

It is known that moldo Iskhak Hasan-ulu, which was the real name of this hero, was born into the family of a Mardaris (spiritual leader) from Margilan around 1844. After finishing rural school, he studied for some time at a madrasah. In 1867, against his father's will, he dropped out of school and settled among his tribesmen from the Boston clan. He roamed a lot with the Kyrgyz, gaining a deep understanding of their joys and sorrows. In 1873, an uprising of the Kyrgyz people against the Kokand oppressors broke out. Iskhak led this uprising, calling himself Pulat, the grandson of Alim-khan. By 1875, the Kyrgyz uprising against Kokand's rule had gained the scale of a popular movement. However, Russian troops, who had previously signed a treaty with Kokand for its protection, came to the aid of the Kokandis. Pulat-khan and his troops tried to resist the advance of the imperial troops but were defeated and fled to the mountains with the remnants of the rebels. On the night of February 18-19, 1876, the wounded Pulat-khan was captured by his own feudal comrades and handed over to the tsarist authorities. On March 1, 1876, he was declared an impostor and hanged in the city square of Margilan.

Here are the details provided in the artistic work "Pulat-khan" by Aman Gaziev: "Mulla Iskhak Hasan-oglu came from the Boston clan of the southern Kyrgyz tribe Ichkilik. His father was a simple herder who served as a mardaris (teacher) at the Margilan spiritual school 'Ak-Madrasah'.

After finishing the rural school 'mektebi', Iskhak first studied at the Kokand madrasah 'Tumkatar', and then returned to Margilan to his father at 'Ak-Madrasah'. In 1867, he dropped out of school for unknown reasons (but it is known that it was against his father's will) and settled in the nomadic camp of the Boston clan. Two years later, he moved to his native village Ukhne; for a short time, he served as an imam at the local mosque. And now he was already in Andijan; here he also held the position of imam in one of the city mosques. Apparently, he lacked funds, and he began trading tobacco-nasvai. The interests of trade forced him to travel frequently to Tashkent. In Tashkent, fate brought him together with Abdu-Mumin, with whom he stayed to live—either as a worker or as a friend and interlocutor.

According to contemporary accounts, historians note that from childhood, Iskhak was distinguished by a lively mind and a penchant for adventure.

"... The stories of Abdu-Mumin about Musulman-kul, Alim-kul (famous temporizers), about the uprisings of the Kyrgyz and Kipchaks that shook the khanate and placed their khans on the throne made a strong impression on the young mullah - Iskhak - and gave rise to his desire for adventure."

It is also known that despite his controversial character, the impostor possessed undeniable charisma, which attracted many people, thus becoming a kind of "Kyrgyz Pugachev" and remained in the memory of the people as a defender against oppressors, since the Kokand territories during the decline of Khudoyar-khan's rule represented a disturbed hive of popular anger.

The Rebel Spirit of the Kyrgyz Tribes

The inevitable uprising was only hastened by the cruel but fruitless attempts of the ruler to regain control of the situation.

The senseless cruelty of this ruler was a parable even among his recent supporters.

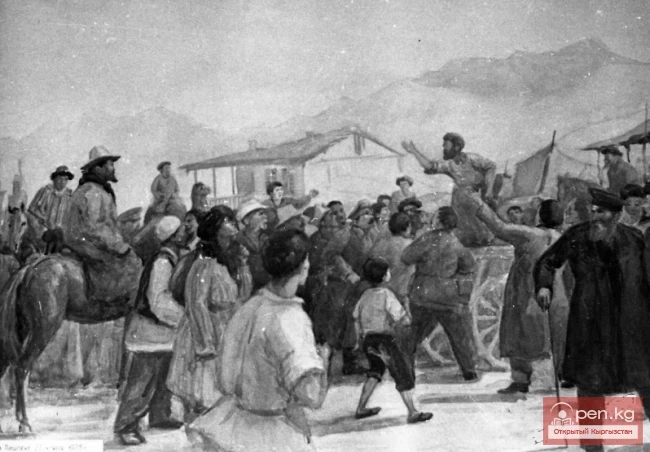

In addition, the unpaid soldiers-sarbaz simply robbed the population, taking everything they liked.

The Orientalist A. Kun emphasized at a meeting of the Geographical Society in the early 1870s that in Kokand, the disease of general discontent against the khan and his entourage had deeply "taken root." Kaufman repeatedly warned Khudoyar about the disastrous nature of his course, but to no avail.

In the spring of 1873-1874, riots repeatedly broke out in the Kokand khanate, but the khan managed to cope with them somehow.

Often the rebels sought help from the Russian authorities but always received a refusal. In the spring of 1875, even the Kokand nobility rose against Khudoyar: the conspiracy was led by the son of the once all-powerful regent Musulman-kul.

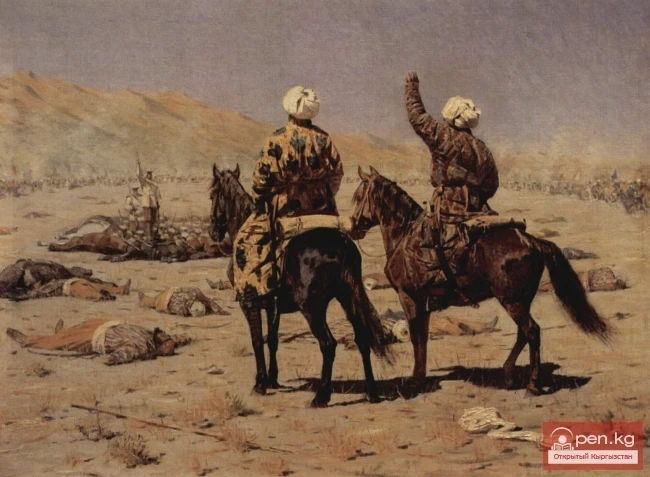

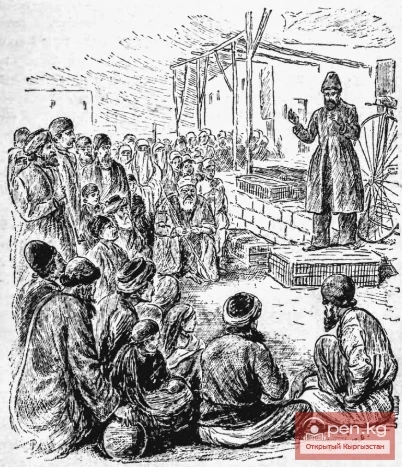

This restless time is described in the aforementioned book by A. Gaziev: "In the late 60s - early 70s of the last century, the vast Kokand khanate was shaken by endless uprisings. The unbearable tax burden caused outrage among all the peoples inhabiting Fergana and the huge mountain ranges surrounding it. Everyone was dissatisfied - both settled farmers - Uzbeks, Tajiks, and nomads - Kipchaks, Kyrgyz, Kazakhs. Tax collectors frequently encountered open disobedience here and there.

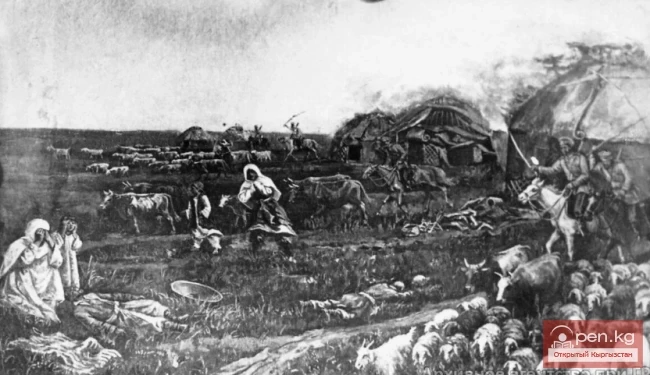

The Kyrgyz tribes particularly stood out in this regard. Let’s give one example. A contemporary of the events, the Russian researcher N. Maev reports: "The harsh winter of 1870-1871 severely affected Kyrgyz livestock..."

Many livestock perished from the harsh conditions. Famine began. But the khan's tax collectors wanted nothing to do with it: take the khan's share! They took the last sheep, condemning people to starvation. In the spring of 1871, herders in the Alai Valley revolted. Atabek datka was sent there with a large military force. He defeated the disorganized, poorly armed militia, hanged 12 main instigators, and built a fortress. However, as another researcher L. F. Kostenko writes, in 1872, the garrison of the fortress along with the datka was caught off guard by the Alai Kyrgyz and was cut down to the last man.

Abdullabek and Pulat-khan: the History of Pride