Governance in Kyrgyzstan in the 18th to early 20th Century

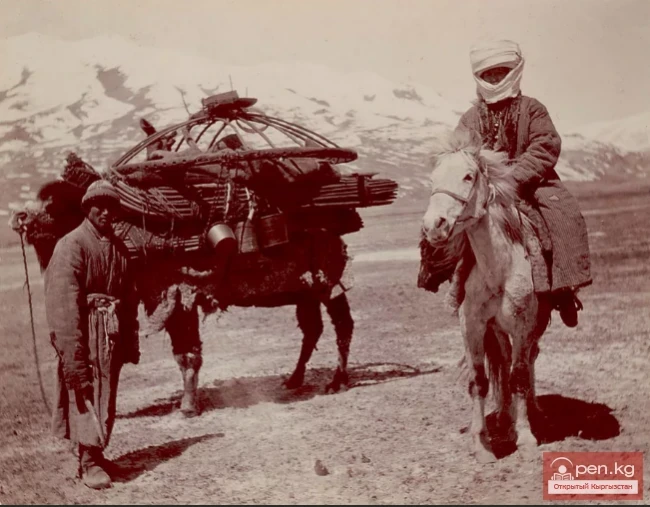

The new period of Kyrgyzstan's history spans from the 18th to the early 20th century. It can be conditionally divided into several stages.

1. Kyrgyzstan as part of the Kokand Khanate (1711-1876).

2. Kyrgyzstan as part of the Russian Empire (1850s-70s — 1917).

During this new period, the Kyrgyz did not have their own statehood and were part of two states. The chronological boundaries of the Kyrgyz's inclusion in either state are expressed vaguely. Therefore, historical processes could not have a logical sequence in terms of time and space.

The Kyrgyz were part of the Kokand Khanate almost since its formation (from the 1720s for the southern Kyrgyz, and from the 1820s for the northern Kyrgyz), but they were often nominally dependent populations, as they relied on the strong support of their tribes. This circumstance allowed them to actively intervene in both the internal and external politics of the khans, especially in matters of succession.

At the beginning of the 18th century, Fergana was a region politically separated from the Bukhara Emirate. The population of the southwestern part of the valley lived under the leadership of the hakim of Khojent, Akboto-biy-Kyrgyz. The central and northern parts of the valley were under the theocratic authority of the Khodja of Chodak and Kasan. The eastern and mountainous parts of the Fergana Valley were mainly under the control of nomadic Kyrgyz. The conditions of relative peaceful life contributed to the strengthening of the influence of the nomadic nobility. The developing external threat from Dzungaria (from the east) and the favorable political situation within the valley created conditions for the renewed political activity of two nomadic clans striving to seize political power from the Khodjas and create a secular state. The result of this activity was the formation of the polyethnic Kokand Khanate in the early 18th century — a union of two nomadic clans: the Uzbek-Ming clan led by Shahruq-biy, a descendant of Babur, and the Kyrgyz clan led by the Khojent Akboto-biy, who was the son-in-law of Shahruq-biy.

The 167-year existence of the Kokand Khanate (1709-1876) can be divided into three major periods.

1. 1709-1800s — the establishment of the Kokand Khanate as a state. During this period, the Fergana Valley was fully incorporated into the Kokand state.

2. 1800-1840s — the time of development and flourishing of the Kokand Khanate. During these years, with the further development of the political-administrative organization of the khanate, both internal and external policies were strengthened. The Kokand Khanate expanded territorially far beyond the Fergana Valley.

3. 1842-1876 — social and political crises intensified in the Kokand state. A popular movement emerged in 1873-1876, which resulted in the fall of the khanate — the Fergana Valley was conquered by Russian colonizers (1876).

Based on sources on the history of Kokand, we can see four political forces that significantly influenced its history: the Sart, the Ming (Uzbeks), the Kyrgyz, and the Kipchaks. While the political power of the Sarts mainly formed the "Sartiya," the Kyrgyz and Kipchaks united in the "Ilatia." The Ming (Uzbeks) in the 18th century constituted a group of nomadic feudalists aligned with the "Ilatia," but by the 19th century they gradually merged into the "Sartiya."

In the years 1709-1760, a group of Mings held political power in Kokand. However, they shared power with Kyrgyz biys (Akboto-biy, the Kokand-Kyrgyz alliance of 1741-1760, Kubat-biy, Azhy-biy, and others). Starting from 1760-1800, the political group of Mings gradually began to align with the "Sartiya" (the policy of Narboto-biy). Although the Mings were in power during the 1800-1840s, their policy was economically controlled by a strong group of Sarts and the military caste of Galchi. As the Mings transitioned to settled life, conditions were created for their transformation into urban populations, increasing connections with the Sarts, and even their incorporation into this category.

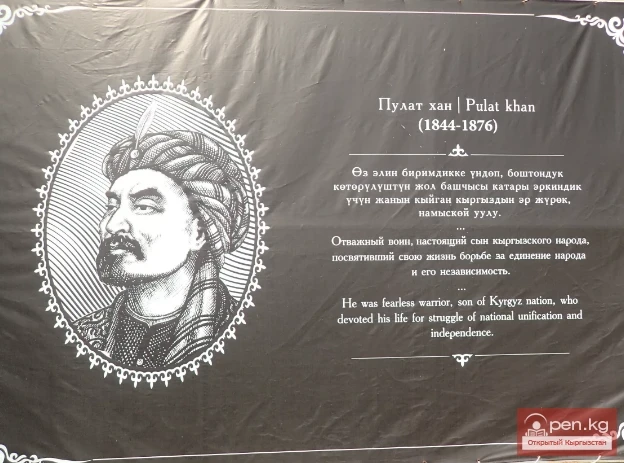

As a result of the political crisis of 1840-1842, the Kyrgyz biys re-emerged on the historical stage, and in 1842-1844 they managed to fully take power into their own hands (Kyrgyz Nuzup-biy). From 1844-1856, the Kipchaks came to prominence (Musulmanqul Minbashi). In 1856-1858, the Kyrgyz regained power. During the rule of Kyrgyz biy and datka Alymbek and Kyrgyz military leader Alymkul from 1858-1865, the khan's authority almost lost its significance, especially during Alymkul's leadership (1863-1865), when the official khan Sultan Seyit was completely dependent on the will of the Kyrgyz biy. Although from 1865-1875 power passed to representatives of the former feudal Mings and the "Sartiya," the Kyrgyz and Kipchak biys actively participated in state administration (Abdrahman Aptabachi, Sher Datka, Narimanbet Datka, Kedeibai Datka, Kurmanjan Datka, and others). During the movement of 1873-1876, the Kyrgyz biys once again tried to seize power — Kyrgyz mullah Ishak Asan uulu was proclaimed khan under the name Polot-khan. This was an attempt to achieve the previous traditional political balance. When a separate group achieved leadership in the power structures, representatives of other groups also participated in governance.

All state positions in the khanate were distributed among representatives of the nomadic Uzbek, Kyrgyz, and Kipchak peoples. Usually, the Kyrgyz and Kipchaks received positions such as atalyk, minbashi, amirlyashker, naib, ynak, eshik-agalyk, and others. For example, under Alimkhan (1800-1810), the son of Narboto-biy, the relatives of his Kyrgyz wife Momunbek and Yrysqulbek were appointed commanders of the Kokand troops — amir lyashkers. Under Madali-khan (1822-1841), Kyrgyz Nuzup held the position of commander-in-chief — minbashi. At the same time, the title of datka was held by Kyrgyz from the Adigine tribe — Alymbek, from the Keseq tribe — Seyitbek, from the Tolos tribe — Polot, from the Avat tribe — Satybaldy, from the Saruu tribe — Azhibek. They were influential figures at the khan's court and held prominent positions in the Kokand state. At this time, the influence of Kyrgyz feudal lords was so high that they held positions in the khanate such as: Nuzup (1842-1844) — minbashi and atalyk, Alymbek Datka (1858-1862) — chief vizier of the khan, Kasym (1853-1856) — minbashi, Alymkul (1863-1865) — amir lyashkar (commander-in-chief of the Kokand army) and atalyk, Atabek — naib (commander of the ground forces and artillery), Sheraly — ynak (commander of the cavalry), Kydyr-biy — eshikagalyk (head of the khan's court), etc. In addition, prominent Kyrgyz feudal lords were awarded titles such as parvanachi, pansad, and were treated with respect. The mother of Kudaayar-khan, the Kyrgyz Jarkynaiym, and the wife of Alymbek Datka, Kurmanjan Datka, had great authority and influence in the khanate. The fact that the last khan of the Kokand state was Kyrgyz Ishak Asan uulu (Polot-khan) also confirms the role of the Kyrgyz in this regard.

All the historical facts mentioned above indicate that the Kokand Khanate was a political regime, a united state of both "Sartiya" and "Ilatia," and thus represented the statehood of both Uzbeks and Kyrgyz, as well as Tajiks. Based on these indisputable materials, it can be stated that the Kokand Khanate was one of the forms of development of Kyrgyz statehood in the 18th-19th centuries.

Read also:

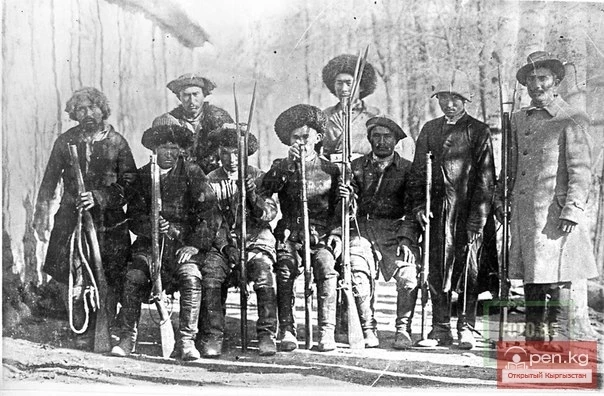

Military Forces of the Kyrgyz in the 18th - Early 20th Century

Since the Kyrgyz did not have their own state formation during the period in question, there is no...

Foreign Policy of the Kyrgyz in the 18th - Early 20th Century

During the period in question, Kyrgyzstan was unable to conduct any foreign policy. However,...

The Territory of the Kyrgyz in the 18th to Early 20th Century

During the period under consideration, the Kyrgyz population occupied approximately the same part...

Kyrgyz in the Russian Empire

The Conquest of the Kyrgyz by Russia. In the last quarter of the 18th century, the southern tribes...

Natural Resources of the Kyrgyz in the 18th - Early 20th Century

Even during the time of the Kokand Khanate, the wealth of the subsoil of Kyrgyzstan was well...

The Population of Kyrgyzstan in the 18th - Early 20th Century

Historical information about the size of the multi-ethnic population of the Fergana Valley during...

Kyrgyz as Creators of the Kokand Khanate

Kyrgyz of Fergana Together with Uzbeks Created the Kokand Khanate Every person, no matter how...

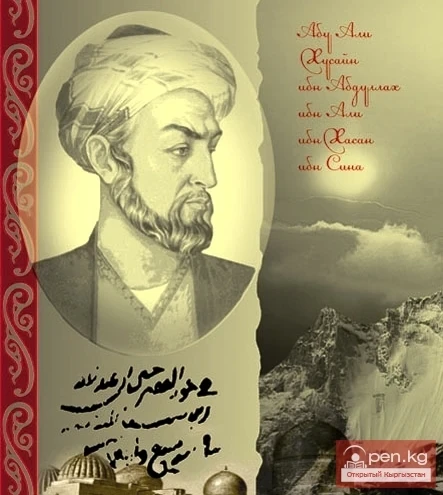

The Science of the Kyrgyz in the 18th - Early 20th Century

The second half of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century marked an era of...

Kyrgyz-Kokand Relations in the 18th Century

The Important Political Role of the Kyrgyz in Fergana at the End of the 18th Century With the...

Formation of the Kyrgyz Autonomous Region

Petition of Kyrgyz Deputies for the Creation of National Statehood After losing their statehood in...

Kyrgyz Management System

POWER SYSTEM AND MANAGEMENT INSTITUTIONS According to historical sources, the Kyrgyz people went...

The Territory of the Kyrgyz in the VI—XVIII Centuries

All political entities of the Middle Ages in the territory of Central Asia somehow affected the...

Events of the Second Half of the 18th Century in Southern Kyrgyzstan

Events 200 Years Ago Let’s return to the events of 200 years ago. What was Osh primarily for the...

Governance in Ancient Kyrgyzstan Before the 6th Century

Kyrgyzstan is one of the world’s centers of human emergence, statehood, and civilization. The life...

Historical Preconditions for the Convergence of the Kyrgyz with Russia

Until the mid-19th century, the Kyrgyz people were under the rule of the Kokand Khanate. The...

The Population of Kyrgyzstan in the VI—XVIII Centuries

The ethnonyms “Turk” and “Turkut” were first mentioned in a Chinese chronicle from the year 546....

Kyrgyz Elite During the Domination of the Kokand Khanate

Kyrgyz Elite During the dominance of the Kokand Khanate, some changes occurred in the social...

Military Forces of the Kyrgyz in the 6th to 18th Centuries

The structure, organization, and supply of the armed forces of the Kyrgyz during that period were...

"Central Asian" Kyrgyz Nomads

Ulus Inga-Tyuri During military clashes, it appears that part of the "Central Asian"...

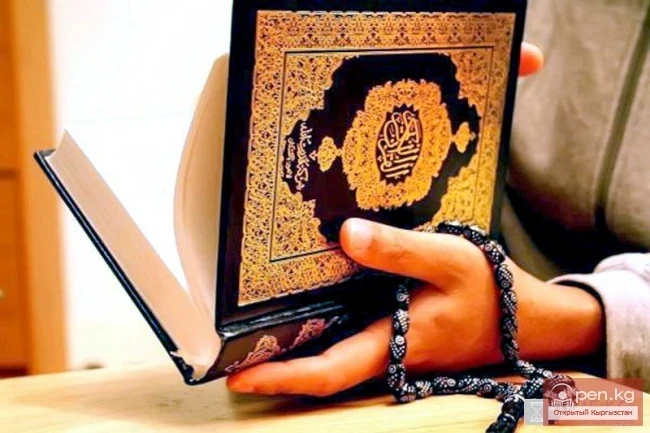

The Religion of the Kyrgyz in the VI—XVIII Centuries

Alongside Islam, the life of the Kyrgyz was widely influenced by customs and traditions of...

Slavery in the Social Structure of the Kyrgyz

Slavery in the Social Structure of the Kyrgyz Among the Kyrgyz of the South, there also existed a...

Kubat Bi

One of the main characters of oral folk art....

Expansion of the Military-Political Presence of the Russian Empire in Central Asia

The First Expeditions of the Russian Empire to Eastern Turkestan In exploring the biography of...

Kyrgyz in the Mongolian Period

Usy, Han-Hena, and Yilanzhou In the "Yuan-Shi," in relation to the land of the Kyrgyz,...

How the Kyrgyz Entered the Kokand Khanate

The Birth and Change of Dynasties of the Future Alay Queen Before delving into the era in which...

The Territory of the Kyrgyz from Ancient Times to the 6th Century

The Saka tribes were divided into three parts. In the southern regions of Kyrgyzstan lived the...

Politics in Eastern Turkestan in the Late 50s-60s of the 18th Century.

The Defiance and Bravery of the Kyrgyz The ambitions of the Qing dynasty and their aggressive...

The Education of Kyrgyz in the 6th to 18th Centuries

The Karakhanid period, as the apex of Turkic civilization, was a time when science and education...

Military Forces of the Kyrgyz during the Soviet Period

During the Soviet period, Kyrgyzstan did not have its own army; its servicemen were part of the...

Ethnic Situation in the Tian Shan in the Second Half of the 15th Century to the First Half of the 18th Century

Ethnic Situation in the Tian Shan in the Middle Ages A comparative analysis of sources and early...

Kyrgyz and Oghuz

“The Kyrgyz Tribe Named Itself Oghuz-Khan” The clan-tribal structure of the Kyrgyz of the right...

Education of the Kyrgyz in the 18th - early 20th century

It is known that in the 18th century, the Kyrgyz, although rarely, used a new writing system, as...

Hanafi School as the Most Tolerant Direction Towards the Pagan Myths and Traditions of the Kyrgyz

Kyrgyz Ayil - an Obstacle on the Path of the Islamization of the People. As historical experience...

Kyrgyz Feudal Lords in Search of Allies

Multi-Step Politics of Kyrgyz Tribes in the Late 18th Century In the late 18th century, Kyrgyz...

Kyrgyz

Kyrgyz K. A. Pishulina rightly points out that only those tribes and clans that participated in...

The Geopolitical Environment of the Kyrgyz Before the 6th Century

Since the Sakas did not have a centralized state, they did not conduct a specific foreign policy....

Kara-Kyrgyz and Balasagun

Balasagun One of the capitals of the Karakhanid state was the city of Balasagun, located in the...

Chigili

Chigili. Chinese sources from the mid-7th century, as part of the Karluk union, mention certain —...

The Economy of the Kyrgyz in the 18th to Early 20th Century

Agriculture. According to the legislative acts of the Russian Empire, the lands of the indigenous...

Kyrgyz Diaspora in Afghanistan

Kyrgyz of Afghanistan. The settlement of the Afghan part of the Pamir by Kyrgyz began in the...

Features of the First Stage of the Uprising of the Kyrgyz 1873-1876.

The National Liberation and Anti-Feudal Character of the Uprising The first stage of the uprising...

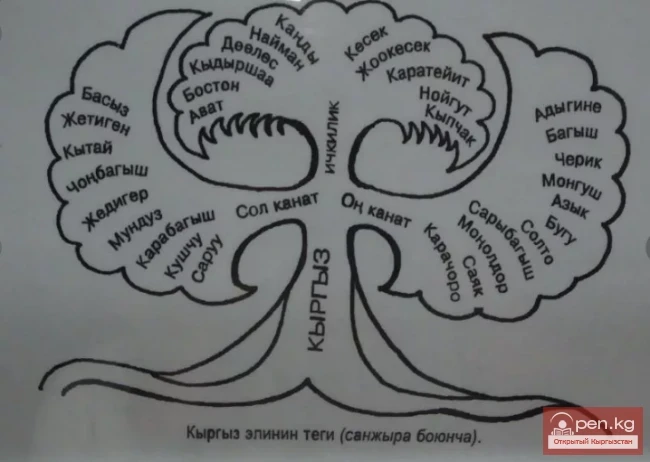

The Division of Kyrgyz into Tribes and Clans

Kyrgyz Division into Tribes and Clans Despite the absence of a centralized state, the Kyrgyz had...

Muhammad Kyrgyz

The situation in Central Asia. In the early 16th century, feudal fragmentation intensified not...

Ancient Kyrgyz — the Earliest West Turkic Tribes

Ancient People — Kyrgyz The Kyrgyz, whose roots go deep into antiquity, lost in the darkness of...

Leader of the Rebels Iskhak Hasan Uulu

“THE KYRGYZ PUGACHEV” Thus, since 1873, the struggle of the Kyrgyz people against the tyranny of...

Tagai Bi (Muhammed Kyrgyz)

In the history of the 16th century, Tagay Bi was celebrated under the name of the great figure...

Kyrgyz of the 19th Century in the Sketches of a British Traveler

Writer Thomas Witlam Atkinson traveled through Central Asia in the mid-19th century. Throughout...

The Performances of the Kyrgyz in the First Half of the 1860s

National Liberation Movement Against the Kokand Khanate On June 1, 1868, a clash occurred between...