The First Expeditions of the Russian Empire to Eastern Turkestan

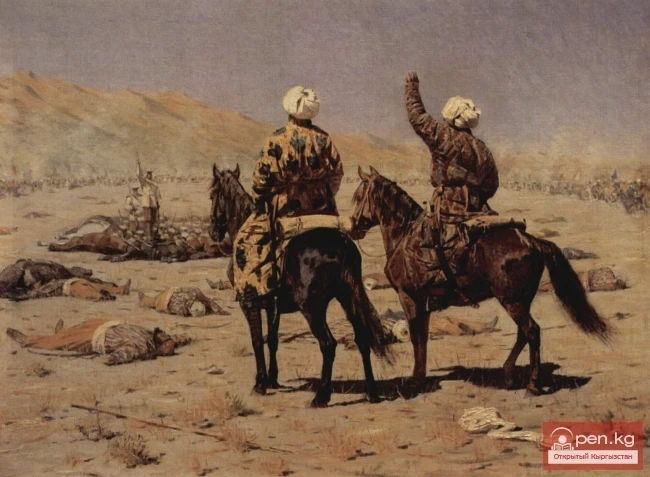

In exploring the biography of Kurmandzhan Datka, one should not forget that she and her people lived in a territory that was at that time at the forefront of the confrontation between two global superpowers - Britain and Russia. In short, the Kyrgyz, as subjects of the Kokand Khanate, found themselves at the end of the last century in the epicenter of a serious geopolitical game. Moreover, each of them had their own, quite pragmatic interest in Central Asia. For the Russians, this interest first manifested itself in 1714. At that time, information was received about the presence of gold-bearing sand near the Uyghur city of Yarkand. Emperor Peter I quickly reacted to this by ordering a campaign to Eastern Turkestan from Siberia. An expedition consisting of almost two thousand soldiers, led by Lieutenant Colonel I.D. Buchholz, reached Lake Yamyshev, where they built a fortress. In the winter of 1715-1716, it was besieged by the Dzungars, and soon the remnants of the detachment were forced to return back.

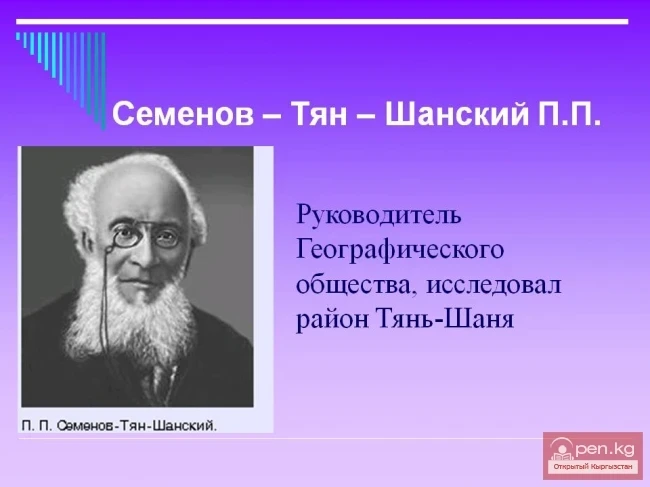

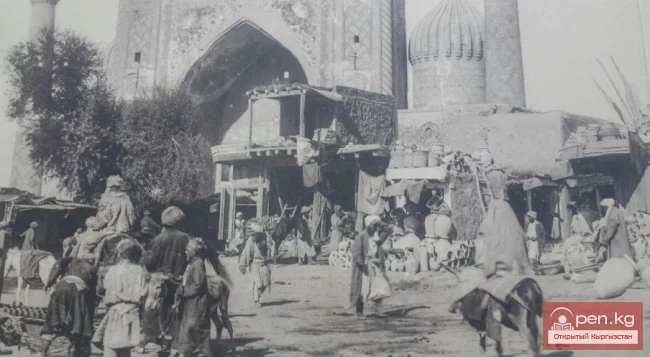

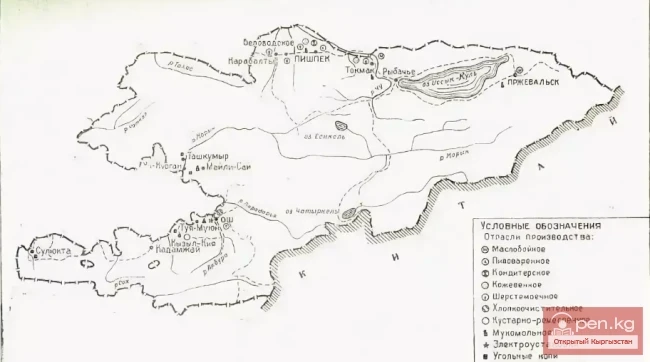

The second attempt to conquer Central Asian lands was made only in the second half of the 18th century. Under Catherine II, the region began to attract the Russians not as a place of potential gold deposits, but as a strategically important point for developing trade with China and India.

Britain, first and foremost, aimed to maintain and expand the territory of British India. The English appeared in India in the early 17th century and established the East India Company there. The victory at Plassey and the vigorous activities of W. Hastings led to the fact that by the end of the 18th century, all of India had effectively turned into an English colony.

Subsequently, with the expansion of the military-political presence of the Russian Empire in Central Asia and the Caucasus in the early 19th century, Russian interests in the region collided with British ones. As emphasized in her research by Kyrgyz historian E.G. Garbuzova, the borders of both colonial powers gradually approached each other, and so-called buffer states were formed, expressing the interests of one or the other of the opposing sides.

In 1801, Emperor Paul supported Napoleon Bonaparte's idea of a joint Russian-French campaign against the English in India. In January of that year, 20,000 Cossacks headed to Central Asia, but in March they received orders to return to Russia due to the emperor's death. After the Napoleonic Wars, plans to conquer the "pearl of the British crown" were not seriously discussed in St. Petersburg.

Starting in 1813, British diplomacy watched with concern the military successes of Russian troops against Persia, which culminated in the signing of the Gulistan and Turkmenchay treaties, by which the territories of modern Armenia and Azerbaijan were ceded to Russia. British military forces were engaged in training and rearming the Persian army and supplied weapons to Circassian rebels (see the "Vixen" case). In Tehran, during clashes near the Russian embassy in Persia, Alexander Griboedov was killed.

In December 1838, the British government decided to take active measures. About 30,000 soldiers invaded Afghanistan and placed a British crown puppet, Shah Shuja, on the Kabul throne.

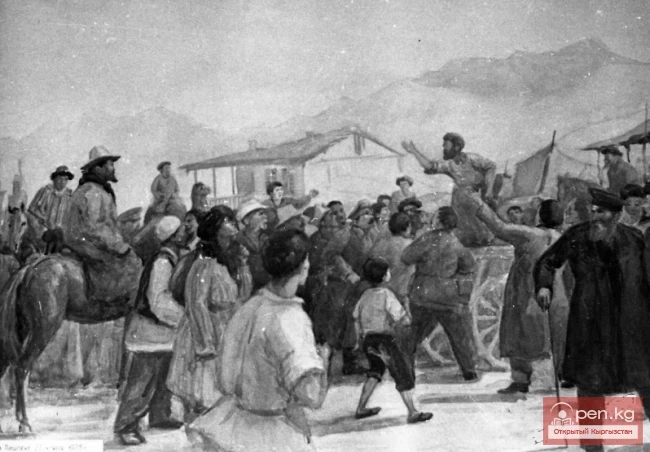

The British occupation lasted three years. In November 1841, a rebellion broke out in Kabul, during which Shah Shuja was overthrown, British agent Alexander Burnes was brutally torn apart by a mob, and other Englishmen were expelled from the country. Thus ended the First Anglo-Afghan War.

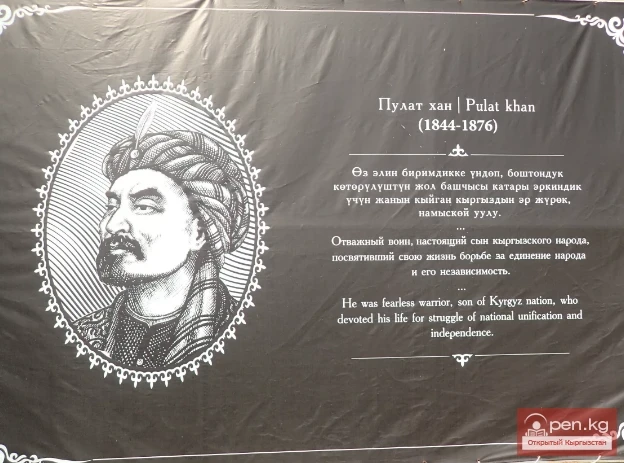

Leader of the Rebels Ishak Hasan Uulu