A New Surge of Anglo-Russian Rivalry in Central Asia

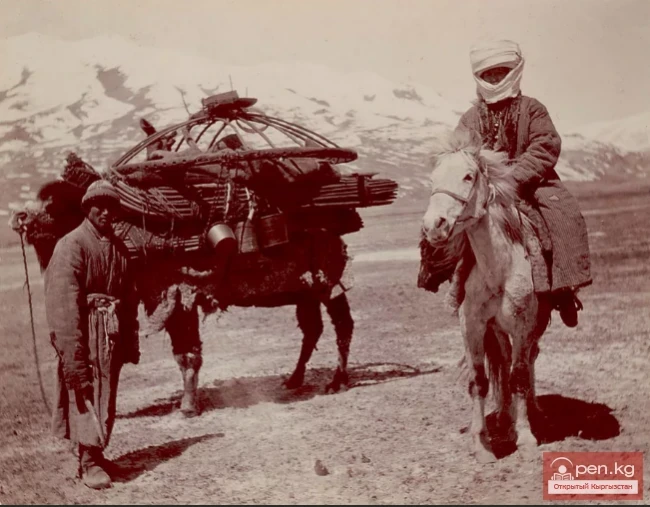

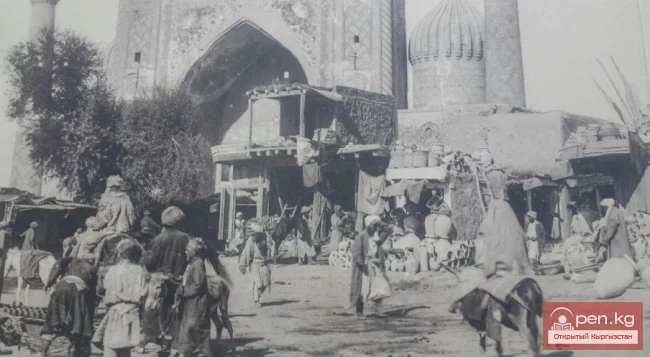

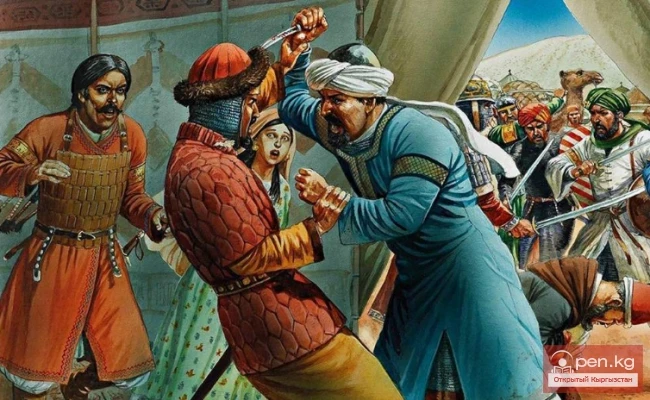

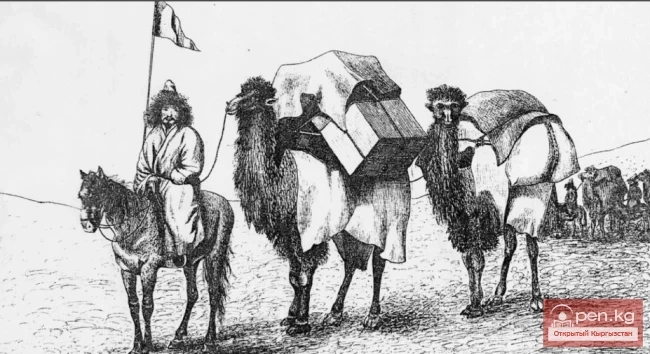

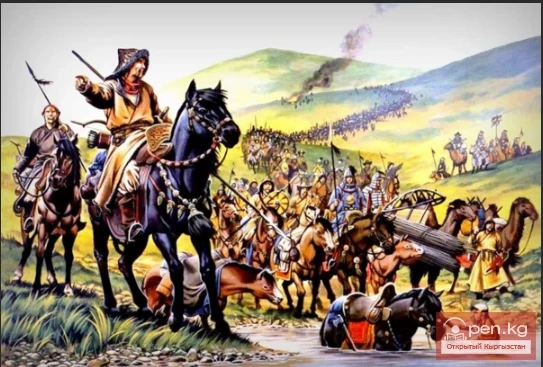

was associated with the Russian conquest of Khiva, Bukhara, and Kokand during the reign of Alexander II. At that time, the process of incorporating Kyrgyz tribes into Russia began, and the question of the allegiance of the Kazakhs and Kyrgyz to the Qing Empire arose, as in the cases of Khiva and Kokand, leading to the issue of territorial demarcation. To this end, the Beijing Treaty was signed in 1860, which outlined the border between the spheres of influence of Russia and China in this region. However, the situation soon began to change radically: in 1862, the Dungan uprising broke out in the provinces of Shaanxi and Gansu, which by 1864 spread to Xinjiang, resulting in the formation of four states: Jety-Shar with its center in Kashgar; the Taranchin Sultanate in Kuldja; the Kalmyk possession centered in Chuguchak; and the Dungan Union of Cities in Urumqi.To stabilize the situation in the region, four years after the signing of the Beijing Treaty, Russia and China signed a new agreement, known as the Chuguchak Protocol. According to it, "the basin of the Naryn River, which is one of the closest routes to Kashgar, was ceded to the Russian possessions... and this border, passing less than a hundred versts north of Kashgar and reaching the Tzung-Lin ridge, thus closes our new Central Asian border, connecting the Orenburg and Siberian lines." Importantly for the further advance of Russian expansion in Central Asia, the protocol legally enshrined the practice of so-called dual allegiance that was already prevalent in the area at that time, whereby any of the nomadic peoples traversing the territory defined by the treaty could be subjects of two or more of the states that signed the protocol. This was also necessary for Russia to stabilize the situation in the border zone and to prevent local Kyrgyz and Kazakhs from raiding Xinjiang. The fact is that from 1864 to 1865, representatives of these two ethnic groups—Russian subjects—crossed the border in large numbers, robbing local residents—Chinese, Manchus, and Kalmyks. On the other hand, as early as 1864, rebels from Kashgar began to oppress the Kyrgyz of the Cherik clan. As a result, their leader Turduke asked the Russians for protection against the raids. However, this desire of Russia to prevent its subjects from provoking a conflict between the two powers was not understood by the local Kyrgyz nobility. As a result, nomads repeatedly attacked Russian servicemen, thereby causing conflicts with the local colonial administration. For example, in May 1865, the leader of the Kyrgyz Bughu tribe, Suanbek, attacked and captured several soldiers and Cossacks sent to stop his crossing of the border.

In the following decade, Britain, having taken control of Afghanistan, gained the opportunity to manage the foreign policy of that state, although, according to the agreement of 1872-1873, the territory of this state was considered a neutral zone. At that time, the actions of Russia's geopolitical opponent—Britain—were colored by the Russophobic activities of Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, whose credo, expressed in his letter to Queen Victoria, was that "our troops must drive the Muscovites out of Central Asia and cast them into the Caspian Sea." To confirm the seriousness of his intentions, Disraeli convinced the queen to accept the title of "Empress of India," which included Afghanistan within the boundaries of the "Indian Empire."

Against the backdrop of the Berlin Congress, Disraeli ordered the start of the Second Anglo-Afghan War. In January 1879, 39,000 British troops entered Kandahar. The Shah made concessions and signed an unequal Gandamak Treaty with the British. Nevertheless, guerrilla warfare continued, and soon the British found themselves besieged in Kabul by nearly 100,000 rebel forces. The military failures resonated in London, resulting in Disraeli losing the parliamentary elections of 1880. His successor, Gladstone, withdrew British troops from Afghanistan and signed a treaty with the emir, under which he committed to coordinate his foreign policy with London.

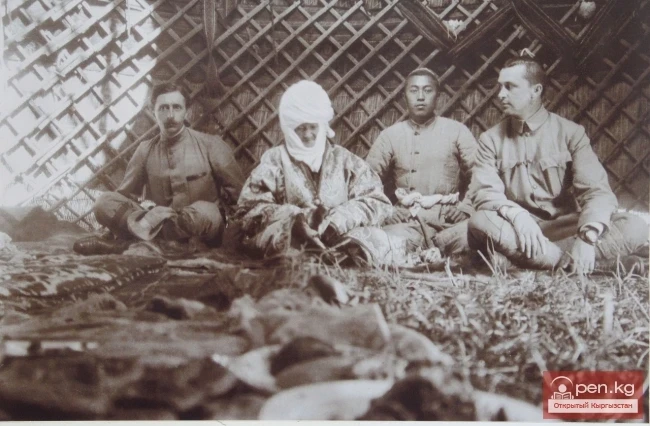

During the next two decades, the Great Game was mainly about intelligence and espionage activities. A key figure in this game was Major General Charles MacGregor of British intelligence.

To strengthen its position in Central Asia in the second half of the 19th century, Russia sought to do so also because of the clearly anti-Russian policies of several political figures who played a significant role in the region. Among such opponents of the empire was the ruler of Kashgar, Yakub Beg (1820-1877). From 1865 to 1866, before separating from Kokand, he caused considerable trouble for the colonial administration. For example, he constantly interfered in the affairs of the border Kyrgyz (Bughu and Cherik), urging them to fight against Russian troops, and built fortifications in the border area. Only after the normalization of diplomatic relations between Russia and Bukhara and Kokand did Yakub Beg make a number of diplomatic concessions to the empire, thereby demonstrating his goodwill towards it.

Expansion of the Military-Political Presence of the Russian Empire in Central Asia