Kyrgyz-Chinese Border

The history of the formation of the modern Kyrgyz-Chinese border dates back to the second half of the 19th century, during the period of Russia's conquest of the Kokand Khanate, when the lands of the Kazakhs and Kyrgyz previously captured by Kokand were gradually incorporated into the Russian Empire. Its new territories in the Central Asian-Kazakhstan region reached the borders with the Chinese Empire: the Semirechye region with its Issyk-Kul (later known as Przhevalsk) district and the Fergana region with its Osh district, part of the Turkestan General Governorship (from 1867 to 1886, then Turkestan Krai), directly bordered Xinjiang (translated into Russian as "New Border") — the northwestern province of the Celestial Empire. This province was established by the Qing after their conquest of the Dzungar Khanate (1859). Thus, issues of Kyrgyz-Chinese relations, including the resettlement of Tien Shan and Eastern Turkestan Kyrgyz, who found themselves in territories controlled by two neighboring empires without defined borders, intertwined with Russian-Chinese relations, with the history of establishing de facto and de jure borders between Russia and China from Tien Shan to Pamir.

However, negotiations on the delimitation of the Central Asian part of the Russian Empire adjacent to the Qing Empire were conducted without the representation of the Turkestan peoples, including the Kyrgyz, without regard for their pressing national interests.

The total length of the state border of the Kyrgyz Republic with the PRC is over a thousand kilometers — 1071.8.

The legal basis for determining the line of the Russian-Chinese, then Soviet-Chinese border, and subsequently the borders of the new independent states — successors of the USSR, including the Kyrgyz Republic, was defined by a number of fundamental bilateral treaties, protocols, and agreements signed over nearly a quarter of a century — from 1860 to 1884.

The most important of these for the Kyrgyz-Chinese section of the Russian-Chinese border were: the Beijing Additional Treaty of November 2, 1860; the Chuguchak Protocol (Treaty) of September 23, 1864; the St. Petersburg Treaty of February 12, 1881; the Kashgar Protocol (Treaty) of November 23, 1882; the Novo-Margelan Protocol (Treaty) of May 22, 1884, and others. These diplomatic documents are recognized as the main foundational basis for the actual delimitation of the adjacent territories of the two states and for resolving the arising disagreements regarding specific unresolved and "disputed areas," gaps in the description and mapping of the border.

Thus, the Beijing Treaty of 1860, in addition to the one signed in 1858 in Tianjin, finally completed the border demarcation of the territories of the two neighboring empires — Russian and Chinese in the Far East, and the determination of the line of the western part of the Russian-Chinese border in Central Asia was already being outlined. The treaty established the condition of a "border line" and roughly indicated the general direction of the Russian-Chinese border from Mongolia to the former possessions of Kokand. The treaty (and this turned out to be a very important part) recognized the principles of the forthcoming establishment of the border line based on the geographical principle of "following the direction of mountains, the flow of major rivers" and the line of existing Chinese outposts. In reality, their interpretations in detail in subsequent practical applications on the ground did not always coincide both at the top and among the border commissioners of both sides. Compromise proposals were often not accepted by the negotiating parties.

This, of course, delayed the conduct and completion of the delimitation and demarcation of the common border.

The Chuguchak Protocol of September 25, 1864 established border service and consular relations, regulated trade on the Kazakh-Kyrgyz part of the Russian-Chinese border. This was of direct interest to Russian merchants and the Kyrgyz-Kazakh population — nomadic livestock breeders, who had long maintained trade relations with the inhabitants of urban centers in the oases of Eastern Turkestan. As for the determination of the "border line" between the territories of Russia and China, it was marked in the text of the protocol and on exchange maps by Russian and Chinese commissioners — Medinsky and Sha in accessible mountainous areas along the peaks of mountains and watersheds of mountain ranges. For example, in point 3 of this protocol, it was indicated that when transferring the border across the Tekes River, it should be conducted along the Naryn-Khalha River (Narynkol) and then pushed to the Tien Shan ridge. From there, following southwest, the border should run along the peaks of Khan Tengri, Sawabtsi, and others, known collectively as the Tien Shan ridge, separating the pastures of the buruts (Kyrgyz) from Turkestan (Xinjiang province of China) and located south of Lake Temurtunor, i.e., Lake Issyk-Kul, and "push" the border to the Tsunlin ridge (Pamir). Such a general, without mentioning specific geographical objects, "straightened" description of the border line over more than 1000 km — from the Kazakh steppes to areas of compact habitation of Kyrgyz tribes — could not fail to cause disagreements and disputes during negotiations and the establishment of the border line. Such and similar circumstances explained the inevitable need for concluding new bilateral treaties and agreements between the Russian and Chinese empires, then between the Soviet Union and the PRC, and in our days — between sovereign Kyrgyzstan and the PRC.

The St. Petersburg Treaty of February 12, 1881 provided for the elimination of identified deficiencies in defining the "border line," as defined by the Chuguchak Protocol of 1864; the appointment of commissioners to inspect the border and establish border markers between the Kashgar region of China and the Fergana region of Russia.

The Kashgar Protocol of November 25, 1882 defined the borders of Russia with China from the headwaters of the Narynkol River to the Bedel Pass (Kokshaala-Tuu ridge) — the modern segment of the Kyrgyz-Chinese border, marked on the spot by commissioners due to difficult mountainous conditions with only one border marker at the named pass.

According to the Novo-Margelan Protocol (Treaty) of May 29, 1884 (in execution of the St. Petersburg Treaty of 1881), the border between Russia and China was established and conducted from the Bedel Pass in the Kokshaala-Tuu ridge, and from it along the main Tien Shan ridge to the Tuyun-Suek Pass and further south to the Uz-Bel Pass in the Sarykol ridge on the Pamir: "Starting from the Bedel Pass, where last year (1883 — Ed. note) border markers were set by the commissioners of both states, the border line goes west along the Kokshaal ridge, which has no mountain passes, then turns along the main Tien Shan ridge to the south" to the Uz-Bel Pass. According to this protocol, 28 border markers were placed on the established border from the Bedel Pass to the Irkeshatam point, while from the latter to the Uz-Bel Pass, border markers were absent.

However, these and other documents on border demarcation, especially the description of the border demarcation, and the maps attached to them did not differ in accuracy and clarity due to the lack of knowledge by members and authorized representatives of the delimitation commissions of the actual structure of the surface of the borderlands, the actual location of mountain ranges, their peaks, rivers, and their directions. Thus, a simplified description of the border line was recorded.

As a result, two versions of the border line emerged between Russia and China. One — contractual, the passage of which was fixed by imperfect, but recognized by both states bilateral documents, the other — actually guarded, differing from the contractual in that it was never recognized bilaterally. Moreover, in the early years of the existence of the PRC, the issue of borders was not acute. Border claims from official Beijing intensified from the late 1950s due to the exacerbation of Soviet-Chinese relations.

The negotiation process for border settlement between the USSR and the PRC, which began in 1964, revealed 25 "disputed areas" covering more than 34,000 km², regarding which the opinions of the two sides on the contractual line of the Soviet-Chinese border did not coincide. Among them were five sections on the Kyrgyz part of the border with a total area of about 3750 km²: about 450 km² in the area of Khan Tengri Peak; about 250 km² in the area of the Irkeshatam Pass; 180 km² in the area of Zhany-Zher; in the basin of the Uzenku-Kuush River about 2840 km² within 5 km of the Bedel Pass; 12 km² in the area of Bozaygyr-Khodzhent.

These "disputed areas" along the state border line were the result of the imperfection of previously adopted treaties, as well as the shifting of the guarded border through unilateral actions by the USSR and the PRC to ensure their security by constructing defensive fortifications and economically developing territories. Moreover, at the negotiations, such actions were mutually recognized as violations of international law.

Read also:

Long-nosed Merganser / Uzuntumshukty Chinese / Red-breasted Merganser

Red-breasted Merganser Status: Category VII, Least Concern, LC. Monotypic species....

Chorotegin (Choroev) Tynchtykbek Kadyrmambetovich

Chorotegin (Choroев) Tynchtykbek Kadyrmambetovich (1959), Doctor of Historical Sciences (1998),...

Prose Writer, Critic Dairbek Kazakbaev

Prose writer and critic D. Kazakbaev was born on June 20, 1940, in the village of Dzhan-Talap,...

The Poet Baidilda Sarnogoev

Poet B. Sarnogoev was born on January 14, 1932, in the village of Budenovka, Talas District, Talas...

Types of Insects Listed in the 2004 IUCN RLTS Not Included in the Red Book of Kyrgyzstan

Insect species listed in the 2004 IUCN RLTS, not included in the Red Book of Kyrgyzstan 1....

Poet, Prose Writer Tash Miyashev

Poet and prose writer T. Miyashev was born in the village of Papai in the Karasuu district of the...

Osmonov Anvar Osmonovich

Osmonov Anvar Osmonovich (1941), Doctor of Veterinary Sciences (2000) Kyrgyz. Born in the village...

Omuraliyev Ashymkan

Omuraliyev Ashymkan (1928), Doctor of Historical Sciences (1975), Professor (1977) Kyrgyz. Born in...

Types of Insects Excluded from the Red Book of Kyrgyzstan

Insect species excluded from the Red Data Book of Kyrgyzstan Insect species excluded from the Red...

Poet, Prose Writer Isabek Isakov

Poet and prose writer I. Isakov was born on September 1, 1933, in the village of Kochkorka,...

Jursun Suvanbekov

Suvanbekov Jursun (1930-1974), Doctor of Philological Sciences (1971) Kyrgyz. Born in the village...

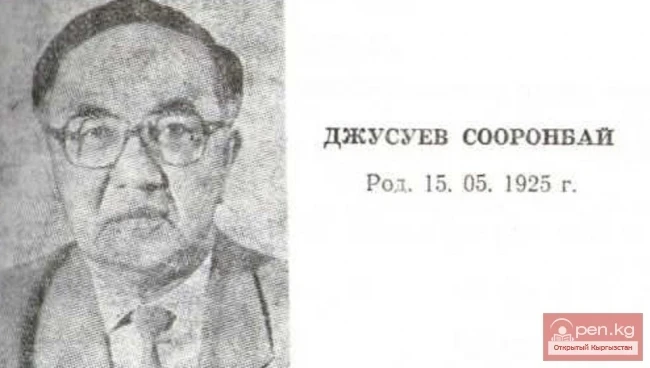

The Poet Sooronbay Jusuyev

Poet S. Dzhusuev was born in the wintering place Kyzyl-Dzhar in the current Soviet district of the...

Critic, Literary Scholar, Poet Kachkynbai Artykbaev

Critic, literary scholar, poet K. Artykbaev was born in the village of Keper-Aryk in the Moscow...

Zhakypov Ybrai

Zhakypov Ybrai (1918), Doctor of Philological Sciences (1967), Professor (1969) Kyrgyz. Born in...

Poet, playwright Dzhomart Bokonbaev

Poet and playwright J. Bokonbaev was born on May 16, 1910 — July 1, 1944, in the village of...

Types of Higher Plants Listed in the "Red Book" of Kyrgyzstan (1985)

Species of higher plants removed from the "Red Book" of Kyrgyzstan (1985) Species of...

Poet, Prose Writer, Playwright Aaly Tokombaev (Balky)

Poet, prose writer, playwright A. Tokombaev was born in the village of Kainy in the present-day...

Prose Writer Duyshen Sulaymanov

Prose writer D. Su laymanov was born in the village of Jilaymash in the Sokuluk district of the...

Salamatov Zholdon

Salamatov Zholdon (1932), Doctor of Physical and Mathematical Sciences (1995), Professor (1993)...

Poet, Linguist Kasym Tynystanov

Poet and linguist K. Tynystanov was born on September 9, 1901—November 6, 1938, in the village of...

Prose Writer Kasymaly Bayalinov

Prose writer K. Bayalynov was born on September 25, 1902—September 3, 1979, in the Kotmaldy area...

Critic, Literary Scholar Bibi Kerimdzhanova

Critic, literary scholar B. Kerimdzhanova was born on October 30, 1920, in the village of...

Poet, Prose Writer Medetbek Seitaliev

Poet and prose writer M. Seitaliev was born in the village of Uch-Emchek in the Talas district of...

Zheenaly Sheriev

Sheriev Zheenaly (1932-2002), Candidate of Philological Sciences (1970), Professor (1991) Kyrgyz....

Poet, Playwright J. Sadykov

Poet and playwright J. Sadykov was born on October 23, 1932, in the village of Kichi-Kemin, Kemin...

Literary scholar, prose writer, poet Dzaki Tashtemirov

Literary scholar, prose writer, poet Dz. Tashtemirov was born on October 15, 1913—October 7, 1988,...

Karymshakov Rakhym Karymshakovich

Karymshakov Rakhym Karymshakovich (1936), Doctor of Physical and Mathematical Sciences (1995),...

Critic, Literary Scholar A. Sadykov

Critic and literary scholar A. Sadikov was born in the village of Kara-Suu in the At-Bashinsky...

Tourist Area Management Program

The project "USAID Business Development Initiative" (BGI), within the tourism...

The Poet Alymkan Degenbaeva

Poet A. Degenbaeva was born on May 12, 1941, in the village of Belovodskoye, Moscow District,...

The Poet Kubanych Akaev

Poet K. Akaev was born on November 7, 1919—May 19, 1982, in the village of Kyzyl-Suu, Kemin...

Ishkeyev Nazarkul

Ishkeyev Nazarkul (1955), Doctor of Pedagogical Sciences (1995), Professor (1996). Kyrgyz. Born in...

Critic, Literary Scholar Abdyldazhan Akmataliev

Critic and literary scholar A. Akmataliev was born on January 15, 1956, in the city of Naryn,...

Critic, Literary Scholar Keneshbek Asanaliev

Critic and literary scholar K. Asanaliev was born on June 10, 1928, in the village of Sokuluk (now...

Sydykov Arstanaaly Arstambekovich

Sydykov Arstanaaly Arstambekovich Painter. Born on February 2, 1952, in the village of Kerben,...

Bicycle Touring Routes by Difficulty Categories

2 difficulty categories...

Zakirov Saparbek

Zakir Saparbek (1931-2001), Candidate of Philological Sciences (1962), Professor (1993) Kyrgyz....

Critic, Poet, Prose Writer Kambarly Bobulov

Critic, poet, prose writer K. Bobulov was born on May 15, 1936, in the village of Osor, Nookat...

Critic, Literary Scholar Kadyrbek Matiyev

Critic, literary scholar Kadyrbek Matiev was born in the village of Ak-Took in the Suzak district...

The Poet Alykul Osmonov

Poet A. Osmonov was born in the village of Kaptal-Aryk in what is now the Panfilov District of the...

The Poet Tenti Adysheva

Poet T. Adysheva was born in 1920 and passed away on April 19, 1984, in the village of...

Poet Musa Djangaziev

Poet M. Djangaziev was born in the village of Karasakal in the Sokuluk district of the Kyrgyz SSR...

Bicycle Tourism Routes by Difficulty Categories

2 difficulty categories...

Estebes Tursunaliev

Estebes Tursunaliev (born 1931) — akyn-improviser, People's Artist of the USSR (1988),...

The Poet Smar Shimeev

Poet S. Shimeev was born on November 15, 1921—September 3, 1976, in the village of Almaluu, Kemin...

Poet, Prose Writer Abdrasul Kylychev

Poet and prose writer A. Kilychev was born in the village of Orto-Sai near the city of Naryn in...

Ecosystems and Protected Areas of Kyrgyzstan

Protected Natural Areas of the Kyrgyz Republic “We, the people, will lose part of our essence if...