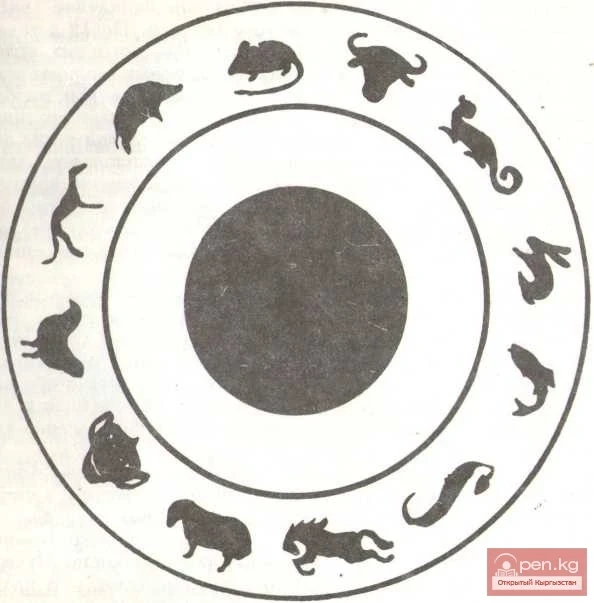

Annual Cycle of Pastoral Livestock Breeding

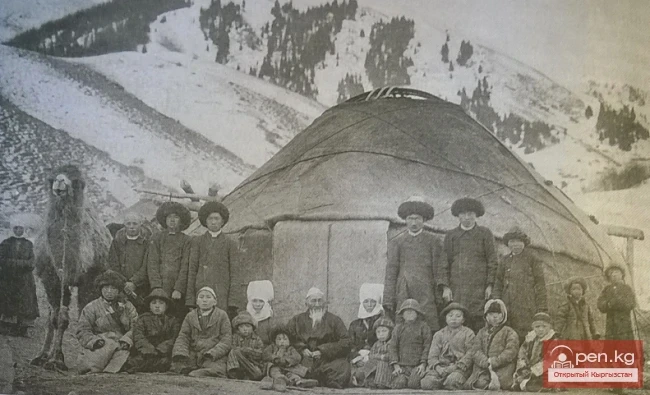

All pastures were divided into summer (jailoo), autumn (kuzdov), winter (kyshtoo), and spring (zhazdoo). The most intense and responsible period was the wintering of livestock. The harsh, prolonged cold period with severe frosts, winds, frequent and heavy snowfalls, as well as the constant need for tebenevka (snow digging) required efforts to maintain the herd, especially since the nutritional value of the plants obtained by animals from under the snow was quite low.

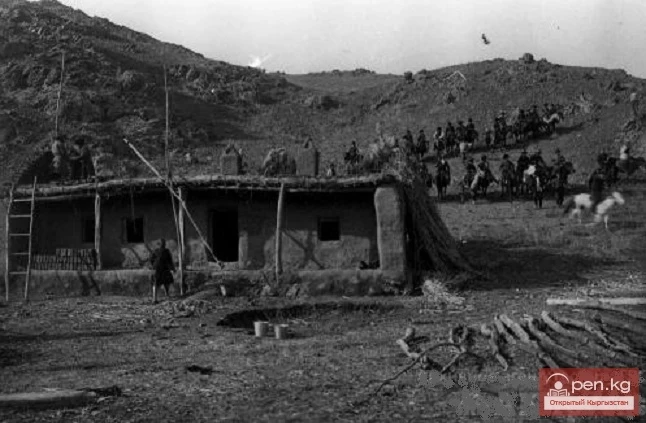

At the end of November - beginning of December, the livestock that could winter in the mountains were driven to convenient places and left until the snow melted, while the rest (as well as the livestock of those owners who mainly engaged in agriculture) were driven to the ails. For winter pastures, places with dense, tall grass and a thin layer of snow cover were chosen (Masanov, 1995. P. 88-90; Rakitnikov, 1936. P. 86).

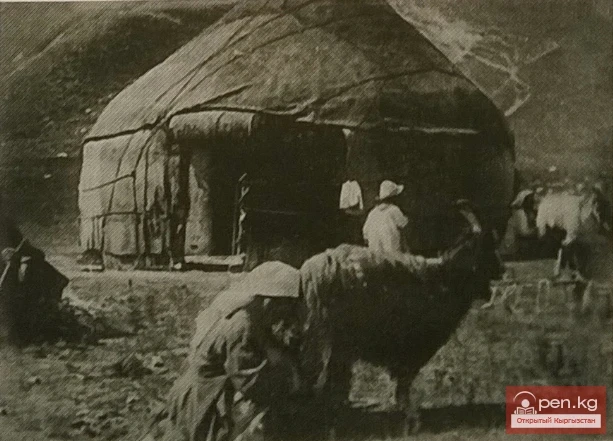

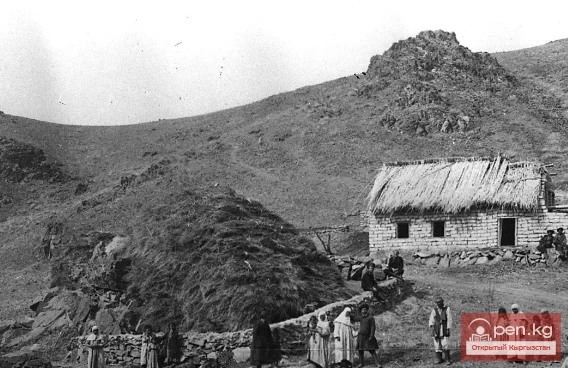

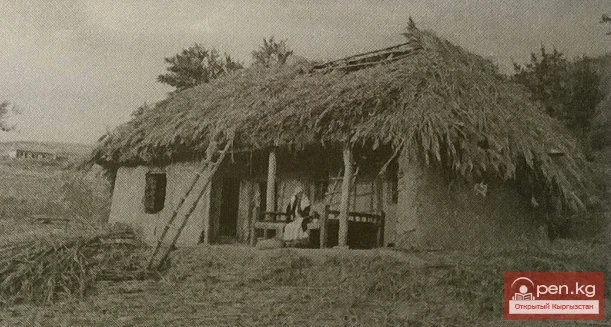

At the winter camps, the Kyrgyz built enclosures for the herd, mainly sheep and goats, from available materials - stone (tash), clay (ylay), branches of sea buckthorn (chychirkanak), and yellow acacia (altygana). The animals were kept behind the enclosure in the open air, with only a few fine-wool rams being provided with special conditions. Large cattle could be kept in closed premises. In the Przhevalsky district in the 1920s, there were 36 winter buildings for every 100 households (Rakitnikov, 1936. P. 86, 178; MKZ, 1911. Vol. 4. P. 70). In some areas, enclosures were not built at all, leaving animals at night in naturally protected from the wind places.

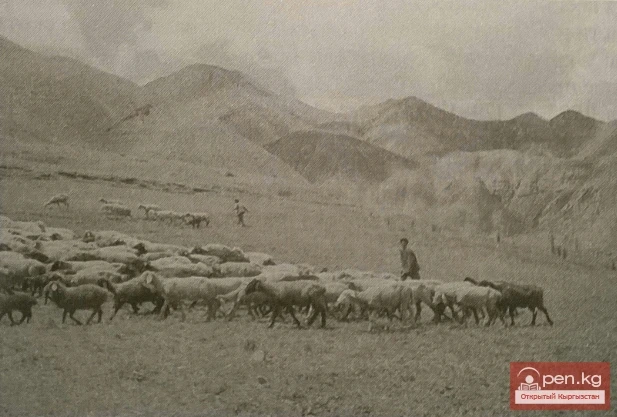

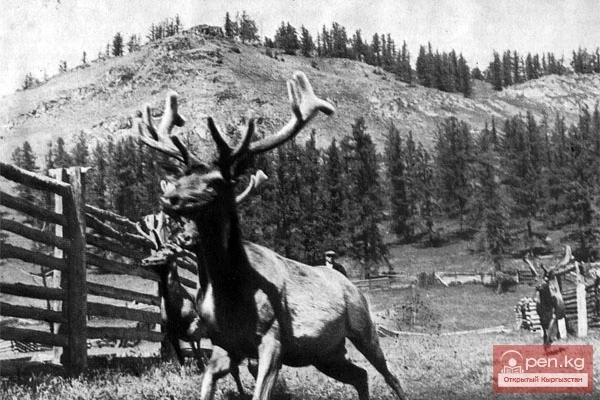

Some herders wintered high in the mountains, choosing almost snow-free hollows and shallow valleys with sufficient forage, good sun exposure, and protection from winds. There were wealthy individuals who did not leave the highlands during migrations at all; in the Przhevalsky district at the beginning of the 20th century, there were about 100 such households (Rakitnikov, 1936. P. 86-88). In the mountains, on jailoo, they left sheep, horses, and yaks (Severtzov, 1873. P. 374), particularly in the valley of the Tulek River, Kara-Kudzhur, Solton-Sary, and others (Sydykov, 1992. P. 123). The number of sheep and goats in winter herds ranged from 300 to 600 heads, while in the herds of wealthy herders, there could be up to 1,000 heads; the optimal size of a herd was considered to be 450-500 ewes or 600-700 rams.

They grazed in narrow strips within 3-4 km from the camp. When pastures were covered with snow, livestock were grazed on the southern slopes of the mountains and hills, strictly adhering to the designated boundaries, as trampled areas could become covered with an icy crust. Horses were grazed both on migratory pastures and on pre-wintering territories.

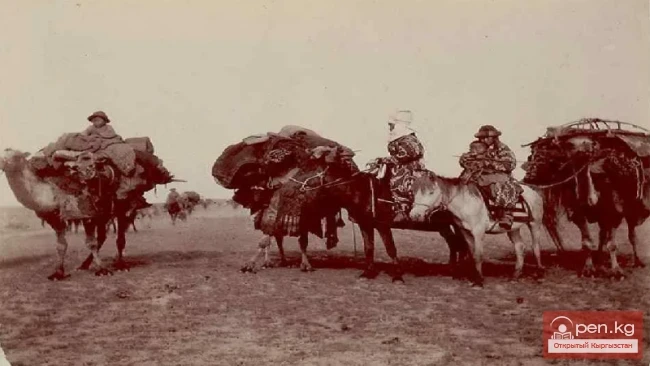

Transport, sick, old horses intended for slaughter remained at the camps. Cows and camels, which poorly tolerate cold and are not adapted to forage from under the snow, were fed with prepared hay and straw (Japarov, 1999). If a strong snow crust formed, tebenevka was used: first, horses were let out to break up the snow, followed by large cattle, and only after that were sheep and goats grazed (Aitbaev, 1957. P. 60; Abramzon, 1971. P. 73). In areas where the snow cover was too high for such grazing, part of the livestock had to be kept in stalls, while part was driven to low-snow and snow-free pastures. The number of livestock wintering on migratory pastures varied from 1/5 of the total herd - where there were many in the valleys of winter pastures - to 2/3 (Rakitnikov, 1936. P. 88, 89),

During the period between the melting of the snow and the beginning of grass growth (late March - early April), herders migrated to spring pastures (kektyoo), located not far from the wintering grounds on plains and foothills, where moisture-loving plants thrived during a short period.

The young stock was expected to appear already on the spring pastures (Masanov, 1995. P. 103).

The period of lambing required great physical effort. A suitable place was chosen, preferably near water sources and in hollows. Ewes were grazed at a short distance from the enclosure. Those animals that were close to giving birth were kept closer to the camp and under observation. If lambing occurred in the presence of a person, they participated in ensuring a successful outcome by removing the afterbirth (ton) and placing the lamb to the ewe for feeding. Wealthy individuals allocated several people to assist the shepherd during lambing.

When fresh grass appeared (the time of kek kubalap kalgan uak), sheep and goats scattered across the pastures, which required special attention from the shepherds. When the vegetation covered the pasture evenly, the intensity of movement decreased. The spring period included castration, branding, shearing, separating flocks from the general herd, etc.

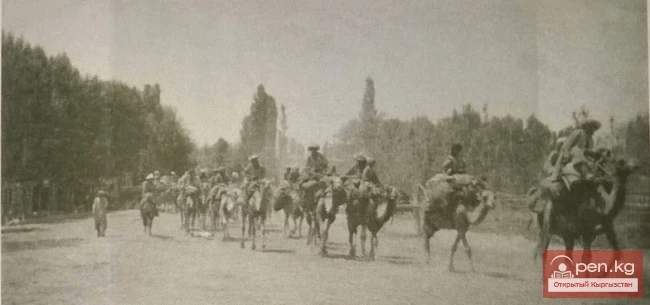

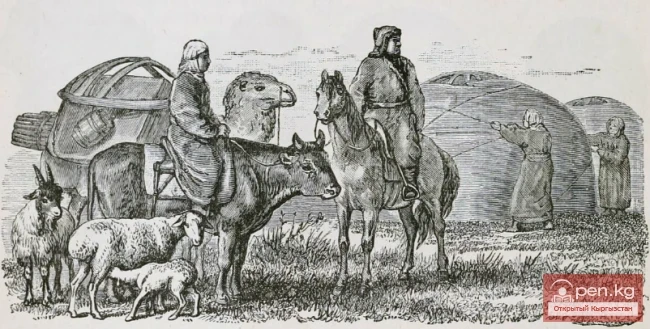

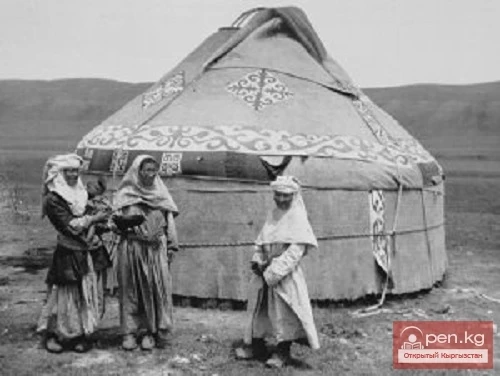

With the onset of summer heat, herders began to drive their herds to high-altitude summer pastures (jailoo), located at an altitude of 2500-3000 m above sea level and higher. This occurred in late May - early June after the harvest of winter crops and spring sowing (Voronkov, 1908. P. 26). The herd was driven a short distance that young stock could easily cover, then a rest was arranged, and only after that did they continue the journey (kozu kyochulop kyochuu - migration possible even for the lamb). They covered approximately 4-5 km per day (Aitbaev, 1957. P. 63). During this time, the grass began to spike (chop zhetildi), marking the "meat time" (maldyn ettenuumezghili) - when animals gain weight. Then came the time of seed ripening (chop byshty) and fattening (maylanuu). The Kyrgyz spoke of this time: "In one day, a sheep eats a thousand varieties of grass" (Baibosunov, 1990. P. 108).

At the summer pastures, livestock grazed until the coolness set in. During this time, they significantly gained weight. Animals were usually driven to pasture early in the morning, and at noon, during the hottest part of the day, they did not graze. While grazing, to ensure the integrity of the herd, shepherds monitored the leaders (rams or goats), as well as weak animals at the back. Guard dogs were reliable helpers for the shepherds. To ensure better fattening, animals were given salt or driven to saline areas.

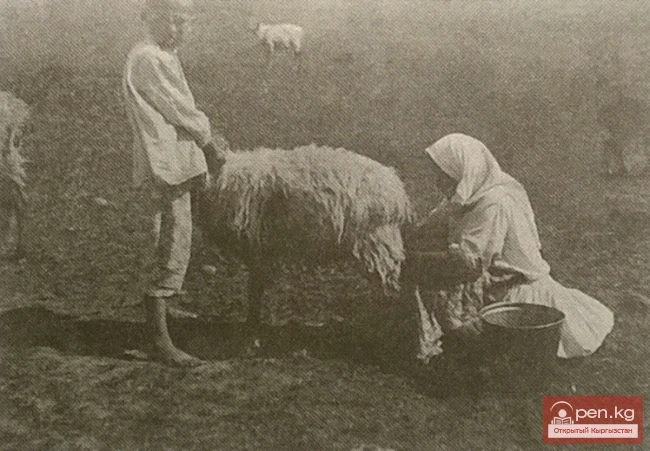

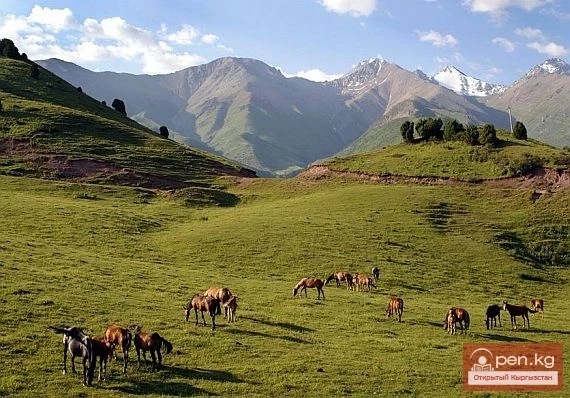

Horses were grazed separately - usually in a closed mountain gorge with water streams, making it difficult to exit. A herd of horses without young stock (subay zhylkilar) could stay in such places around the clock, while mares needed to be brought to tether several times a day for milking. Wealthy individuals milked mares three times a day, while the poor did so seven or more times (Fielstrup, 1920). Foals remained tethered all day, and from evening until morning, they were with their mothers.

In early autumn, herders migrated to autumn pastures (kuzdoo). It became cold in the high mountains already in late July-August, and herders left from there (Fielstrup, 1924). The migration to kuzdoo occurred in mid or even late October, when the first snow fell and the forage was eaten (Aitbaev, 1962. P. 18); generally, they tried to stay longer at summer pastures for better fattening of the livestock. Small livestock was kept in the general herd - both males and lambs. Horses were also grouped in a common herd.

For camels, this period was also favorable. Upon returning from summer pastures, herds of animals grazed in the foothills (boksyo), where they fed on wormwood (ak shybak), zhyltyrkan (kohi), saltwort (kuuduruk), and others. They also grazed on mowed fields (zhnivye). In autumn pastures, sheep mating and their autumn shearing took place: fat-tailed sheep were supposed to be sheared twice a year, with autumn wool being valued higher than spring wool (in total, a ewe gave 3-4 kg) (Abramzon, 1971. P. 79; Aitbaev, 1957. P. 58, 59; Kushner, 1929. P. 18-20).

Composition of the Kyrgyz Herd