Use of Pastures by Kyrgyz People

The natural conditions themselves suggested how to use the pastures more effectively, considering their seasonality. The non-simultaneous growth of vegetation in different zonal areas historically determined the sequential use of pastures: koktoo — spring pastures, jaiyloo — summer pastures, kuzdoo — autumn pastures, and kyshtoo — winter pastures, the boundaries of which have mostly remained unchanged to this day. Driving animals to seasonal pastures better provided them with forage, while the variety of grasses created a sort of prevention against infectious diseases. As a result of the alternation and strictly uniform use of pastures, the grass cover was protected from depletion, ensuring its recovery.

This form of using seasonal pastures was widely applied earlier in collective and state farm animal husbandry, allowing for the avoidance of feed imbalances through more appropriate distribution of pastures by seasons of use and the introduction of supplementary feeding for animals.

After winter, plants initially awaken in the plains and foothills, that is, in the lower vertical zone. Here, spring plants with a short growing season usually prevail; before the hot summer days arrive, the seeds of plants in this zone manage to ripen and fall off. These pastures were popularly called koktoo — spring pastures, and the period of time — chöp chykty — the grasses have appeared.

Initially, livestock grazed in the foothills, then on the warmed southwestern slopes. Later, grasses on the northern slopes grew and ripened, and the livestock were driven to them.

With the onset of summer, plants in the lower zones finished their growing season, while the vegetation cover in the upper zones only began to flourish: the time of chöp zhetildi arrived, i.e., the grass reached the height suitable for grazing (the heading phase — beginning of flowering). This period is called ettenuu by the Kyrgyz — meat time, when animals regain the weight lost during winter and gain weight. Then came the ripening time (the phase of fruiting and seed ripening), the time of maylanuu — shearing. During this period, the Kyrgyz said: "In one day, a sheep eats thousands of varieties of grasses."

Long-term studies by botanists confirm how finely all these features of the mountainous region were noted by the Kyrgyz people. The coincidence of maylanuu with the phase of fruiting and seed ripening is quite understandable. During this time, sheep consume not only leaves and young shoots, in which the content of protein, fat, and other nutrients significantly decreases, but also the fruits of various grasses, including plants that are usually inedible or poorly edible (such as Eremurus kodonopsis, and others), as well as ears, spikes, and panicles of cereals.

With the onset of cool weather, closer to autumn, the grasses on the jaiyloo begin to dry out, and the time comes, called by the Kyrgyz chöp kuurady — the grass has dried (end of vegetation). During this time, herders descend to the lower zones and graze numerous herds on autumn and winter pastures, again on the hay in the foothills, on the sunny, southern side of rocky slopes, where there is a lot of ak shybak — wormwood, zhyltyrkan — kochia, and other plants.

All pastures had natural boundaries (ridges, watersheds, rivers, hollows), along which it was easy to outline daily grazing areas, that is, a kind of enclosures. In this system, the pasture around the camp was first grazed, and the sequence of use of its individual sections was mainly determined by the unevenness of the growth and ripening of grasses on different slopes. Then the shepherds with the livestock moved to a new location. The transition from one pasture to another (between seasons) was also determined by the growth and ripening of grasses, so pastures even within one season are located at different altitudes.

Read also:

Kyrgyzstan, Autumn-Winter 2014-2015

YouTube user Alexey Nikitin previously published a video about the beauty of Kyrgyzstan...

Indian Crested Porcupine / Jeyre, Chutkjor / Indian Porcupine

Indian Crested Porcupine Status: Category VII, Lower Risk/least concerned, LR/lc, poorly studied...

Summer in Kyrgyzstan

No one has seen Kyrgyzstan from such angles before. YouTube user Alexey Nikitin published a video...

Chesneya Woolly / Tuktuk Coin / Kostyczewia, Pilose Chesneya

Chesneya villosa Status: EN. One of the three very rarely encountered species of this genus in...

Chikeev Asylbek Asakeevich

Chekeev Asylbek Asakeevich (1962), Doctor of Physical and Mathematical Sciences (1998), Professor...

Noble Deer (Tien Shan subspecies), Maral / Bugu (male), Maral (female) / Asiatic Red Deer, Tien Shan Maral, Tien Shan stag

Noble deer (Tien Shan subspecies), Maral Status: Category IV, Endangered, EN C2a(i): R. A sharply...

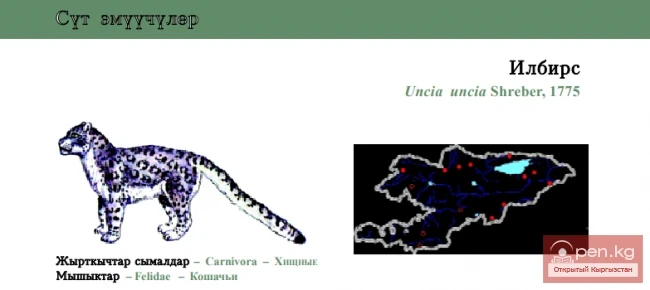

Snow Leopard / Ilbirs / Snow Leopard

Snow Leopard Status: III. Critically Endangered, CR C2a(i): R, C1....

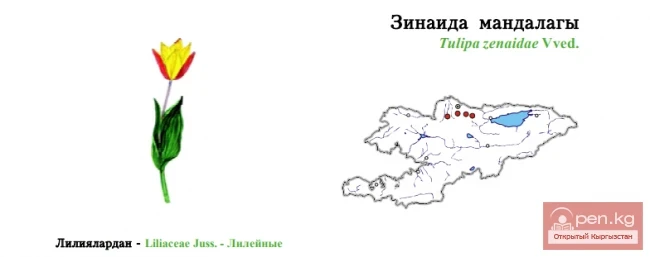

Zenaida's Tulip / Zinaida Mandala

Zenaida’s Tulip Status: VU. A narrowly endemic species of the Kyrgyz Ridge, at risk of rapidly...

Issyk-Kul Marinka / Carp Fish / Issyk-Kul Marinka

Issyk-Kul Marinka Status: 2 [EN: D]. A rare taxon inhabiting Lake Issyk-Kul. Its...

Niedzvetzki’s Apple-tree \ Red-leaved Apple

Niedzvetzki’s Apple-tree Status: VU. Very rare, endemic, endangered species with a small...

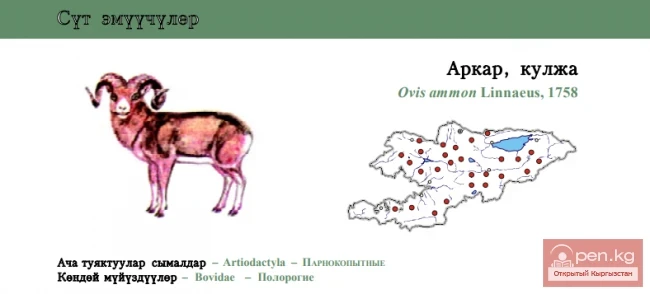

Mountain sheep / Argali, kulja / Argali

Mountain Ram Status: Three subspecies with different statuses inhabit the territory of the...

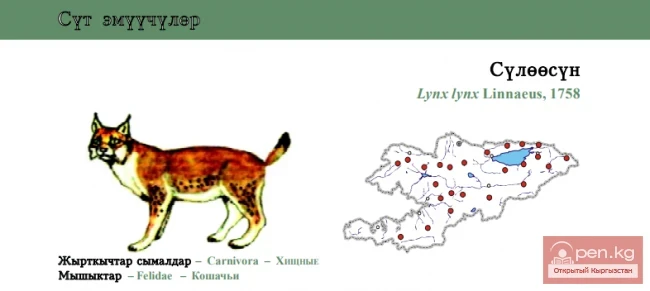

Lynx / Sulyoyosun / Eurasian Lynx

Lynx Status: V! category, Nearly Threatened, NT. A rare subspecies Lynx lynx isabellinus Blyth,...

Nathaliella Alai / Alai Nathaliella / Nathaliella

Nathaliella alaica Status: CR B2ab(iii). A rare, endemic species of a monotypic genus of Himalayan...

Crane Beauty / Karkyra / Demoiselle - Crane

Demoiselle Crane Status: Category VI, Near Threatened, NT: R. One of two species of the genus in...

Jumping Jerboa / Koshayak / Jerboa

Jerboa Status: Near Threatened, NT: R...

Acantholimon Dense / Nyk Työ Tamán / Dense Prickly-thrift

Acantholimon compactum Status: VU. A very rare narrowly endemic species....

Asian Barbastelle / Asiatic Wide-eared Bat

Asian Barbastelle Status: VI category, Near Threatened, NT: R....

Pennywort with Bristly Fruits / Memёsu Tuktuu Tyinchanak / Chaeto-fruited Sweet Broom

Chaeto-fruited Sweet Broom Status: EN. A relic endemic species found in walnut-fruit forests....

Steppe Harrier \ Kubargan Kulaaly \ Pallid Harrier

Steppe Harrier Status: Category VI, Near Threatened, NT. One of 4 representatives of the genus in...

Short-winged Bladder-senna / Baibiche Chekey

Short-winged Bladder-senna Status: VU. One of three very rarely occurring species of this genus in...

Twelve-dentate Onion

Twelve-dentate Onion Status: VU. A narrowly endemic species of the Chatkal Ridge. Description. A...

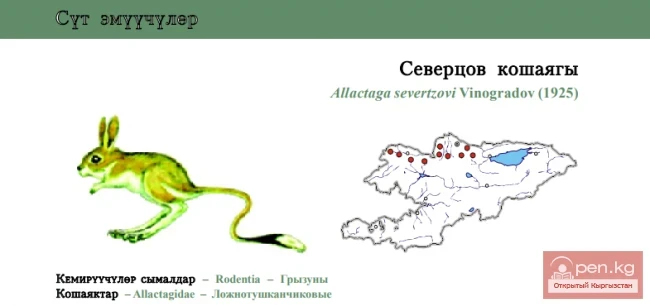

Severtzov’s Jerboa

Severtzov’s Jerboa Status: VII category, Lower Risk/least concerned, C^//rare, poorly studied...

Lesser Horseshoe Bat / Kidik Taka Tumshuktyu Jarganat / Малый подковонос

Lesser Horseshoe Bat Status: Category VI, Near Threatened, NT: R. A species with a declining...

Broad-eared bat / Erin's bat / European Free-tailed bat

Broad-eared bat Status: Category VII, Lower Risk/least concerned, LR/lc....

Brown Bear \ Ayyu / Brown Bear

Brown Bear Status: VII category, Lower Risk/least concerned, LR/lc. A rare subspecies of bear...

Dwarf Ammopiptanth / Baibiche Chekey / Ammopiptanth Dwarf

Dwarf Ammopiptanth Status: EN. A rare species with a disjunctive range. One of two known...

Chonbasheva Cholpon Keneshovna

Chonbasheva Cholpon Keneshovna (1959), Doctor of Medical Sciences (1998) Worked as a professor at...

Kosopolyan Turkestan / Turkestan Kosopoljanskia

Kosopoljanskaya Turkestanian Status: VU. One of the two endemic species of this genus found in...

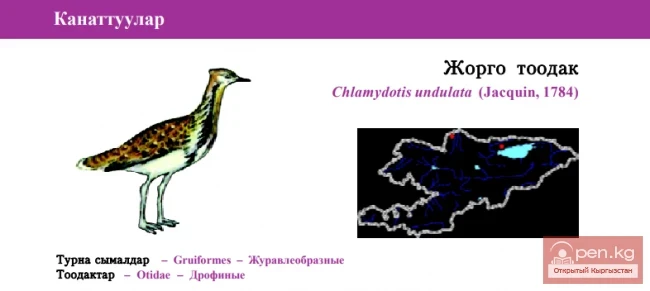

Houbara Bustard / Gorgeous Bustard / Houbara Bustard

Houbara Bustard Status: III category, Critically Endangered, CR: R, A1. The subspecies Chlamydotis...

Events on Saturday, August 3 in Bishkek

Saturday Events in Bishkek "Culture" Summer Edition. For those tired of the heat, 191Bar...

Mazaris Longhorned Wasp / Mazaris Yellow Wasp / Kuznetzov’s Longicorn Wasp

Kuznetzov’s Longicorn Wasp Status: Category III (LR-nt). A naturally rare Central Asian species...

Issyk-Kul Scaleless Osman / Kök Chaar, Ala Buga

Issyk-Kul Scaleless Osman Status: 2 [CR: D]. Lake form, very rare, critically endangered....

Tulip Aspiring Upward / Chatkal Yellow Tulip

Chatkal Yellow Tulip Status: VU. An endemic species of the Chatkal Ridge with a decreasing...

Small Jerboa / Kidik Koshayak / Small Five-toed Jerboa

Small Five-toed Jerboa Status: VII category, Lower Risk/least concerned, LR/lc....

Turkestan Smoke Plant / Turkestan Fumitory / Microfumitory

Turkestan fumitory Status: Category ENBlab(iii,iv). A representative of the monotypic [60,...

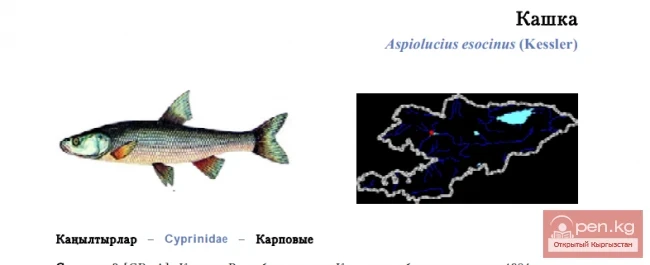

Pike Asp / Kashka / Pike Asp

Pike Asp Status: 2 [CR: A]. Listed in the Red Book of the Kyrgyz SSR in 1984. A rare...

Turkestan Tuvik \ Kuryonkyokuryktuu Kyguy / Shikra

Turkestan Shikra Status: VI category Near Threatened, NT: R. One of ten species of the genus in...

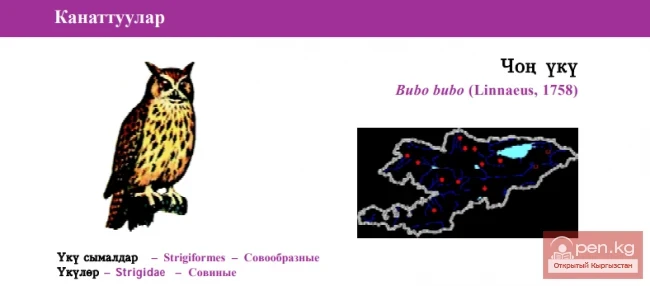

Eurasian Eagle-Owl / Chon Uku / Owl

Eurasian Eagle-Owl Status: VII, Least Concern, LC. In Kyrgyzstan, Bubo bubo hemachalanus Hume,...

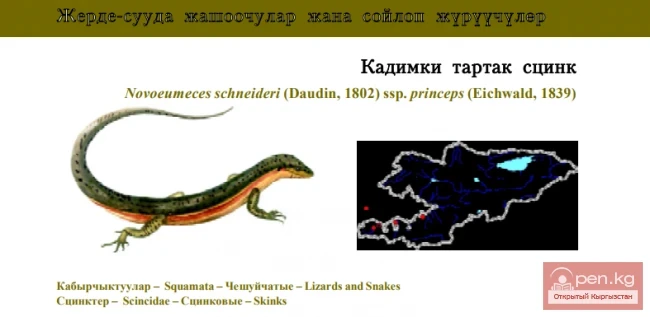

Schneider's Gold Skink / Kadimka Tartak Skink

Schneider’s Gold Skink Status: Category ENB1ab(iii). A sporadically distributed south-Turanian...

Menzbier's Marmot / Menzbir Squirrel / Menzbier's Marmot

Menzbier’s marmot Status: V category, Vulnerable, VUB1+2c. Rare species. Endemic to the Western...

White-headed Vulture \ Aк кaжыр / Eurasian Griffon

Eurasian Griffon Status: Category VI, Near Threatened, NT: R. One of two species of this genus in...

Long-tailed Sea Eagle / Pallas’s Fish Eagle

Pallas’s Fish Eagle Status: V category, Vulnerable, VU, Cl. A species at risk of extinction. One...

Dressing / Chaar Kusen / Marbled Polecat

Marbled Polecat Status: III category, Critically Endangered, CR: R, Cl. Close to extinction. The...