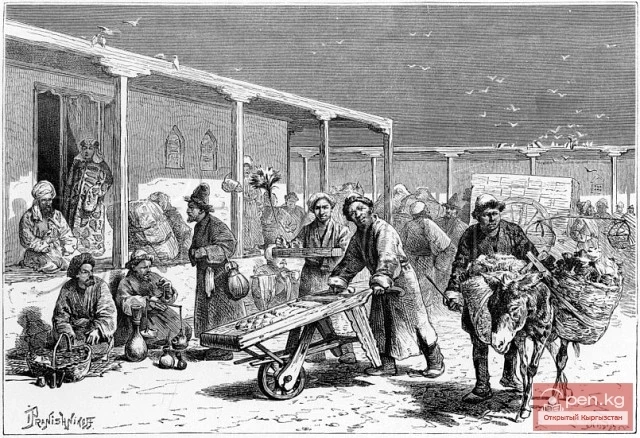

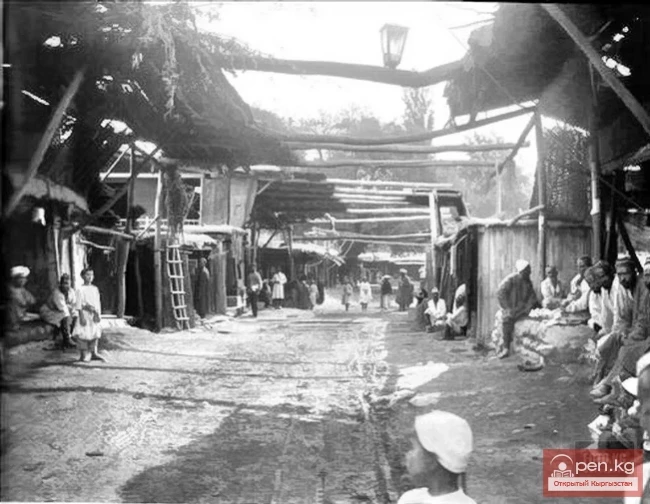

Tax Burdens on the Working Population of the City

Taxes were levied on grain crops from the townspeople — kharaj, on melons — tanap, on livestock — zyaket, on trade — also zyaket, taxes were collected from handicraft production, for legal transactions, for inheritance of property, for gathering firewood, etc. It is no wonder that the Russian orientalist A. L. Kun, who collected tax records after the fall of the Kokand Khanate, wrote about the tax burden: “It seemed that only air remained, for the right to breathe it cost nothing.” Taxes were collected both in kind and in money. Labor obligations in the form of ashar (should not be confused with ashar — mutual aid and collective labor of united neighbors) were widely used. Naturally, military service was a heavy burden — the so-called "blood tax."

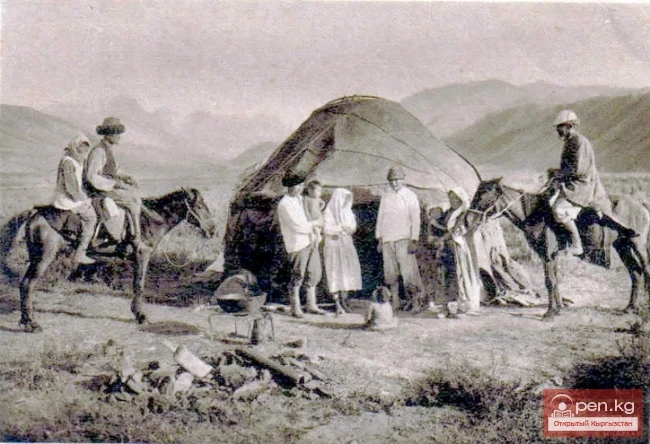

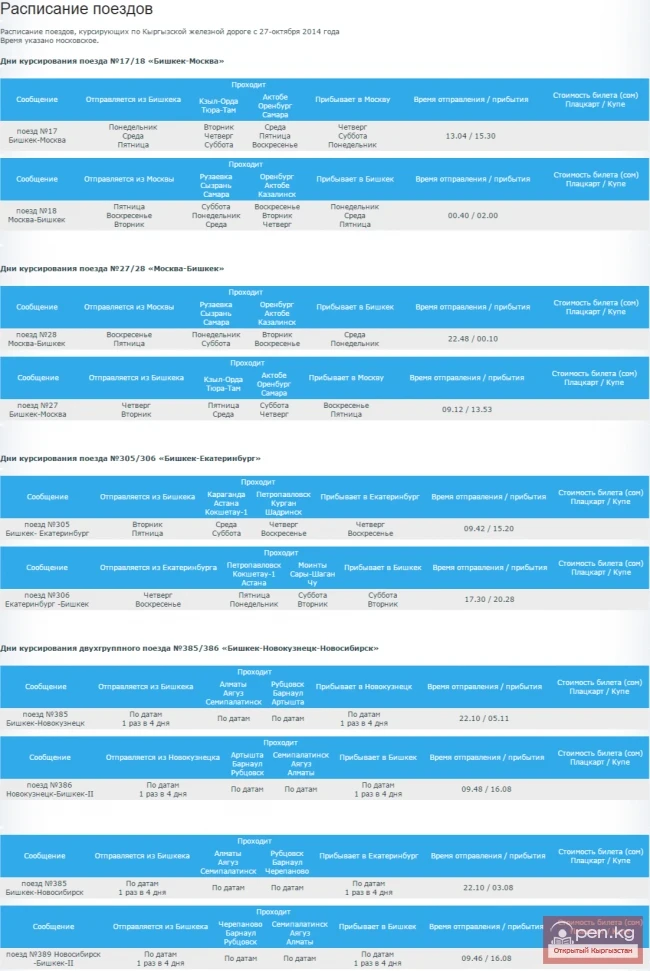

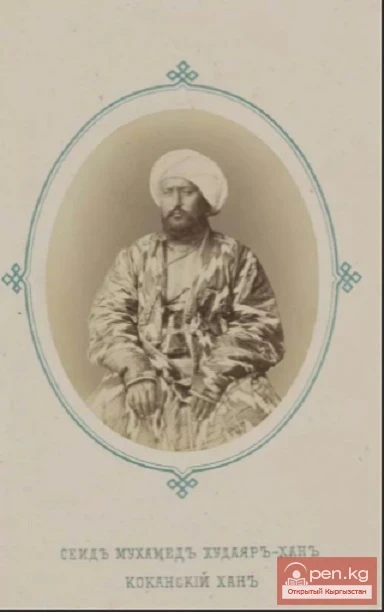

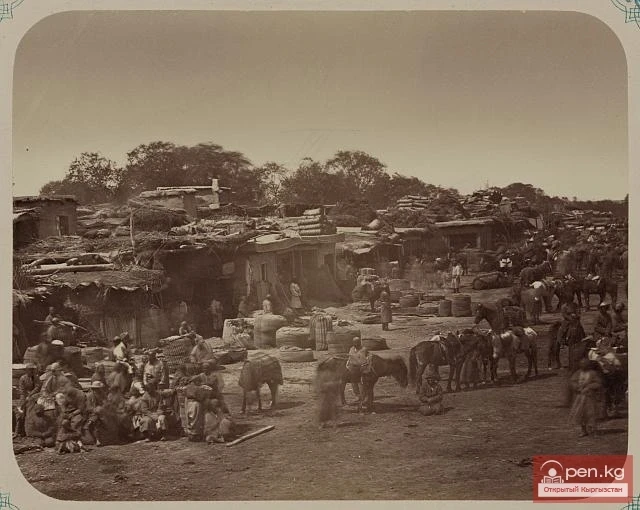

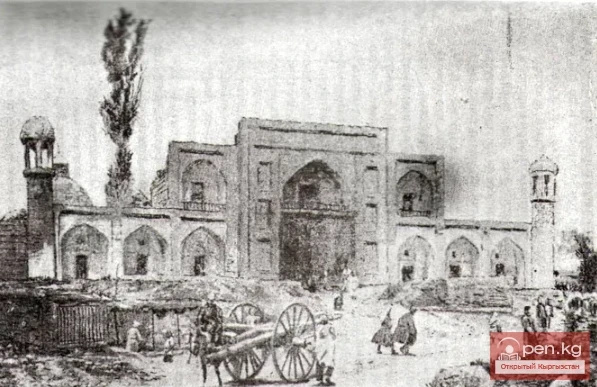

The first rulers of Kokand, who managed to capture Osh, tried to levy taxes from its residents and nearby Kyrgyz nomads for their benefit. The oppression of the Kokand feudal lords increased as their power was established in southern Kyrgyzstan. The amounts of tax revenues to the khan from Osh and its surroundings in the 1840s-70s can be judged by the data from Russian travelers of the past century. For example, the natural tax to the khan from Osh in 1840 amounted to 12,000 chariks (a weight measure of 4 poods) of grain — 10,000 chariks of jujube and 1,000 chariks each of wheat and barley. Converted to Russian banknotes, this brought an income of 38,400 rubles. There was a persistent trend of increasing these taxes, as new and larger taxes were established by each new ruler ascending the throne in the khanate.

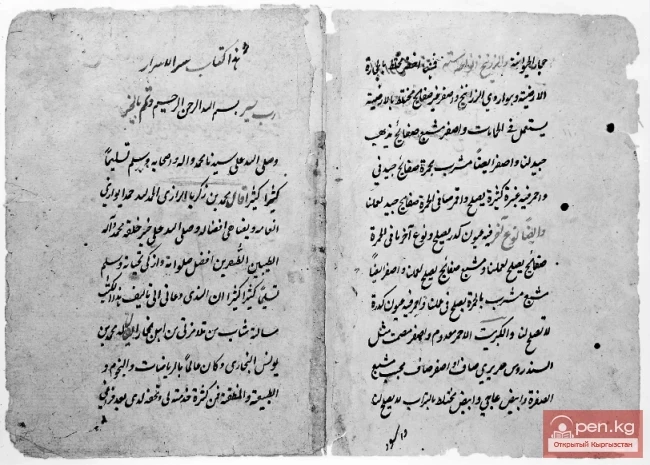

The tax in money from the nomads was likely introduced earlier than from the settled population. In any case, by the 1870s, it had become much more widespread. This is evident from the documents of the Kokand khans' archive, where taxes, for example, in the Margilan district, including Osh, Aravan, and other Kyrgyz areas, were named in natural terms (in chariks of wheat, rice, cotton, flax, opium poppy), while from livestock — in monetary terms (in tanga and tilla).

Monetary zyaket represented a significant item of income for the khan. It is enough to say that in the last years of the khanate, the zyaket from the livestock of the nomads (ilat) of Osh and Aravan, from the tribes of Nayman, Teip, Urgu, Biga, Uighur, Chuchuk, amounted annually to one lakh sixty-two thousand nine hundred and forty tanga - At the same time, the records (defters) indicated either the district, or the clan and tribe, or the leader of the nomads.

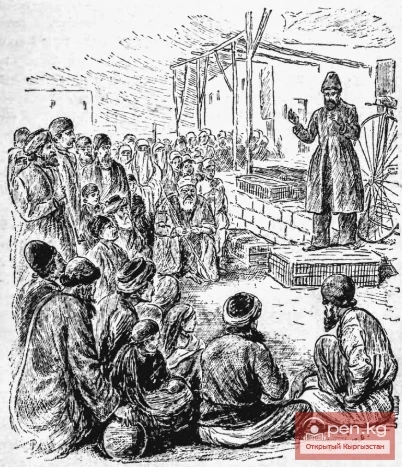

The lack of clear accounting of the tax capabilities of the population led to the widespread development of the tax farming system in Kokand and other cities of the khanate. A. L. Troitskaya, analyzing the economic archive of the Kokand khans, concludes that the last three decades of the Kokand Khanate were characterized by a tax farming system of taxes and government levies. The practice of tax farming descended from the khan to the beks, and from the beks — downwards.

Sometimes the khans, bypassing the beks, themselves leased tax collection from certain districts of the bek's estate or city quarters to tax farmers.

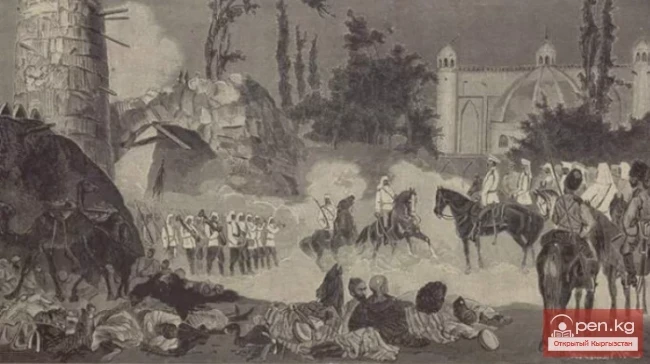

After the occupation of Fergana in 1876, the head of the city of Kokand reported to the military governor of the region: “The entire financial structure in Fergana under the khans was based on the tax farming system, which alone gives serious reason to doubt the accuracy of the information contained in the defters; it is well known that tax collectors always deceived the khans.”

All this led to the fact that when collecting taxes through the tax farming system, “neither time nor deadlines were observed, and often even the amount of the tax itself.” To collect the required amount from the population, tax farmers borrowed money at interest from the nearest merchants, subsequently collecting the tax from the workers, not without profit for themselves.

Thus, merchants gradually became involved in the orbit of tax exploitation of the working population. Receipts from tax farmers of a stencil nature have been preserved: “A subscription stating that instead of the money given by them to the Kokand authorities for the society... — they now with the consent of the society [collect] the following kharaj from the residents.”

To obtain a lease or tax farm for the collection of kharaj, a petition was usually submitted to the khan or bek and a corresponding document was received, while the population of the given area was notified by a special decree or notice, listing the amount of grain leased or farmed. “Apparently,” A. L. Troitskaya notes with full justification, “the lease or tax farm was in some cases resold several times. The first tax farmer or lessee of the kharaj was a sarkar or trusted person of the khan or bek, who in turn leased the kharaj to an amlakdar under his control.”