Tax Exploitation in Pre-Revolutionary Osh

After the fall of the Kokand Khanate on February 17, 1876, the Turkestan administration established the "Commission for Clarifying Tax Obligations and State Property of Fergana," which presented a report with its proposals on March 11 of the same year "on the method of revenue collection and the abolition of certain revenue items that do not comply with our laws." Lieutenant General Kolpakovsky imposed a resolution on the report: "Everything proposed for Kokand should be practiced in other cities of the Fergana region." This provision was naturally extended to the city of Osh.

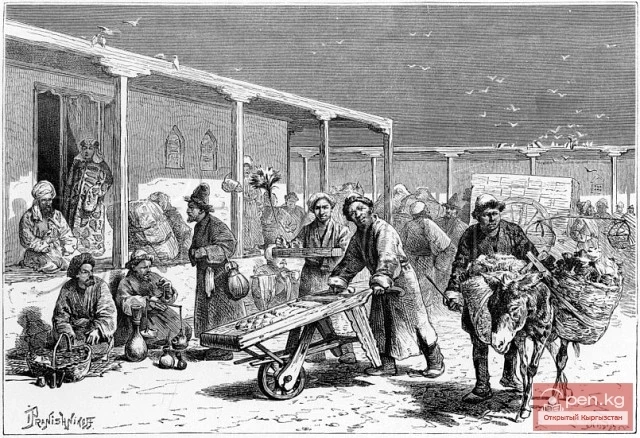

Among the state revenue items were all state properties belonging to the former khans (and there were such in Osh) — houses, lands, gardens, shops, workshops, etc. City revenue items included fees: weight, zakat from industrial establishments, and others. However, hereditary and wedding fees (tarine and nikahane), certain market fees, salt tax, guild fees, broker fees, forest fees, coal fees, and others were abolished.

The levies that, in the opinion of the Russian administration, led to particularly uncontrolled and unrestrained exploitation and that were incompatible with or contradicted Russian legislation were abolished.

Four years later, it was time to introduce a general tax administration regulation for the population of the Fergana region, which existed throughout Russia. To familiarize the urban and rural population of the Fergana region with the new tax regulation, the Turkestan Governor-General Kaufman issued a manifesto on April 6, 1880 — an address to the population of the Fergana region. "The residents of Fergana... now, after four years under the scepter of the Russian Tsar, I find it possible to introduce transformations in the entire Fergana region: public, tax, and land."

The purpose of the tax reform was "to replace the existing land payments under various names with one clearly defined state tax." Along with the permanent rate of the state tax, the size of land obligations, i.e., "fees to meet local needs," was also determined. "I proceed with the aforementioned transformations in confidence," Kaufman stated pathetically, "that they will contribute to the development of agriculture, the eye source of your well-being, the elimination of harmful disputes, and many abuses inevitable under the currently existing orders." There is no doubt — the intentions are good, but in reality — one form of exploitation, crude and openly predatory, was replaced by another, no less exploitative.

Even among the townspeople, the main sphere of production in pre-revolutionary Osh was agriculture.

Hence, the main form of tax exploitation was the land tax on the harvest of grain or melon crops, and on livestock. Then came the levies on handicraft production and trade. These are state taxes. Hired workers and craftsmen were exploited by employers who appropriated their surplus product.