The Role of Osh in Other Regions of Central Asia

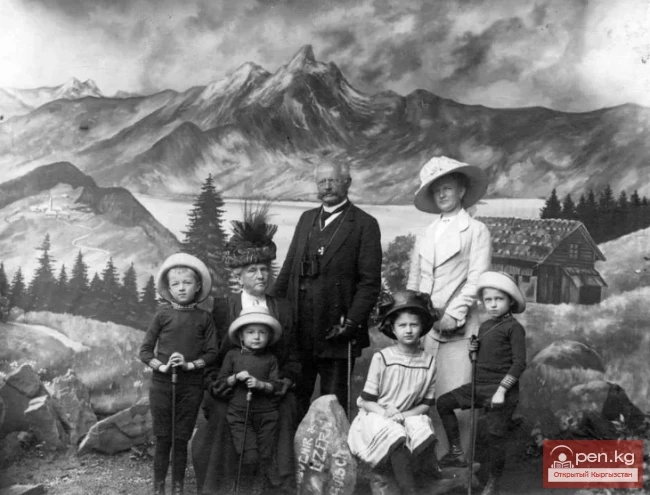

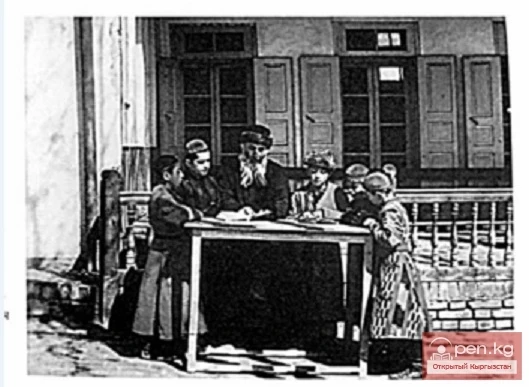

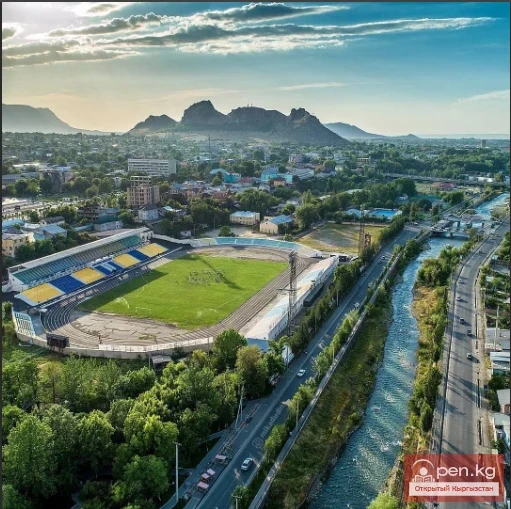

Positive changes occurred not only in daily life but also in people's consciousness. Russian and other merchants began to bring goods here that the local population had not seen before. The construction of roads and bridges began. Pack transport was replaced by wheeled transport. Postal services and telegraphs appeared, as did secular schools... The influx of non-native populations, craftsmen, and intelligentsia into the city increased. It became the homeland for many Russians, Ukrainians, Tatars, Armenians, Poles, Germans, Georgians, Jews, and other peoples. The new Osh owes its revival, as mentioned above, to two captains: Sergey Topornin (1853—1916), commander of the 4th Turkestan Linear Battalion, and Mikhail Ionov (1846—1923), the first district chief of Osh. These undoubtedly talented and energetic officers worked together effectively for a long time. Upon their recommendation, the first urban development plan for Osh was developed in the regional center—New Margelan—according to which it began to be built quite successfully. The responsibility for constructing the new city fell on Topornin S. N., who had to accommodate the garrison's personnel practically on a wasteland. Essentially, without construction machinery, with an acute shortage of building materials, and without experienced builders, it was necessary to quickly build the city before winter: auxiliary premises, a dining hall, a bakery, a bathhouse, stables, warehouses, etc. Topornin S. N. completed his remarkable life journey in Tashkent at the age of 63 and was buried in a family crypt near the cemetery church.

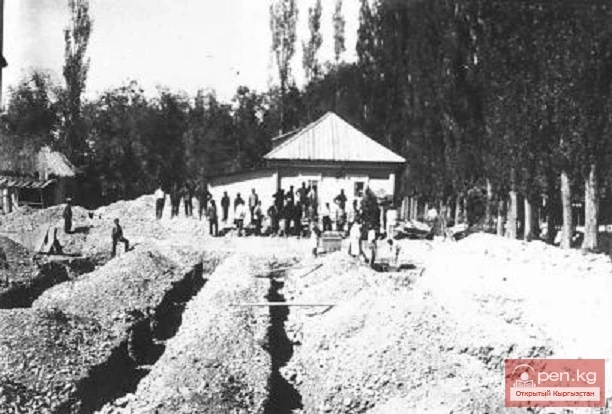

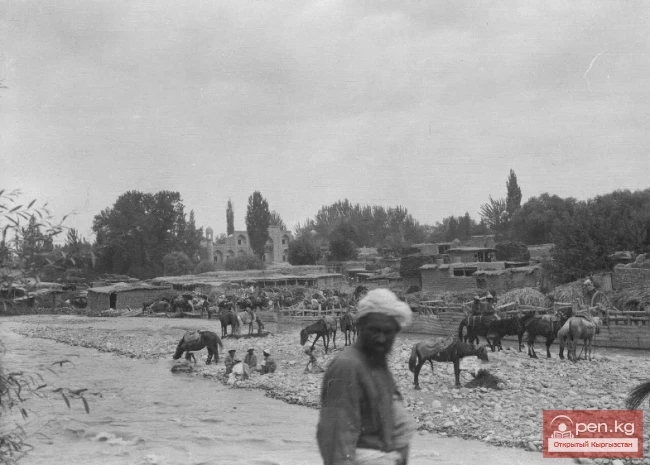

The tsarist authorities established a new part of the city next to the old city of Osh as their military-colonial stronghold.

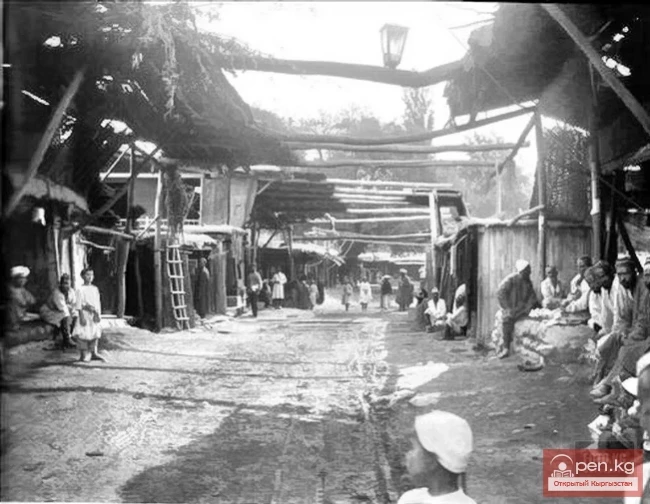

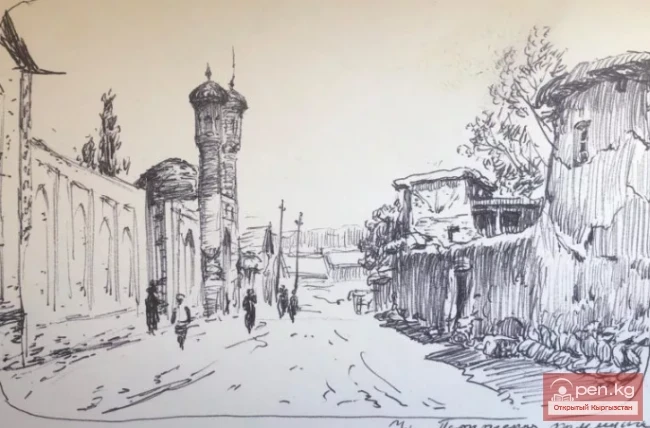

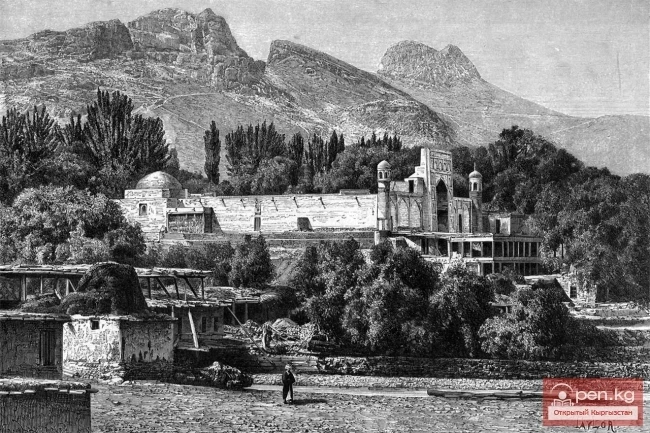

The new "Russian" part of the city was favorably distinguished from the old city with its labyrinth of narrow, winding streets, dead ends, and haphazardly built adobe houses, with a vast market, numerous shops, and mosques, by a well-planned grid of wide streets lined with poplars and European-style houses. Here were located the colonial administration offices, the estates of Russian officials, merchants, industrialists, and townspeople. At that time, the city was divided into quarters (mahallas) in terms of construction and planned structure. Each quarter had a name, such as Khojagan, Char-Kucha, Jindalik, Kyrgyz-Alibay, Tokmok Karayach, and others.

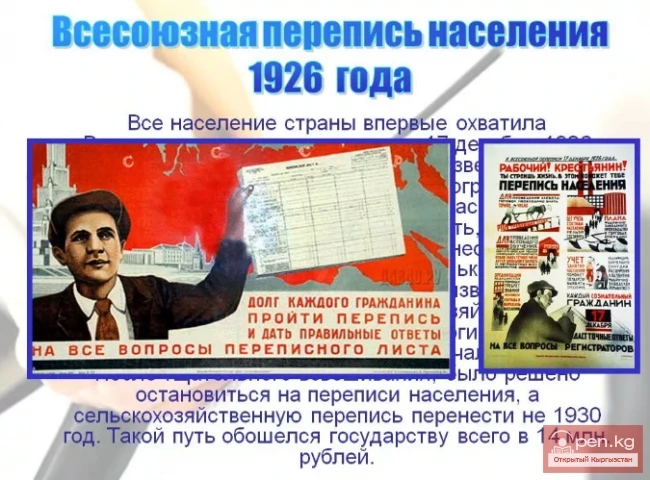

The difference in the development of these two parts of the city was noticeable for a long time, with the old "native" city, which was only superficially overseen by the authorities in a police-fiscal manner, continuing to be the center of all economic and spiritual life of the local population. Thus, in 1882-1883, the new city had fewer than 50 houses and one and a half hundred Russian residents (excluding troops), while the old city had about 2800 houses and several thousand residents. During these years, the Osh district had 16 state and 78 public buildings—mainly religious, 4 caravanserais, and 852 shops. In 1914, the new city had 140 courtyards and about 1200 residents, while the old city had over 6300 courtyards and more than 46000 residents. The national composition was very diverse, but the majority were Uzbeks. There were about 1000 Kyrgyz in Osh in 1911.

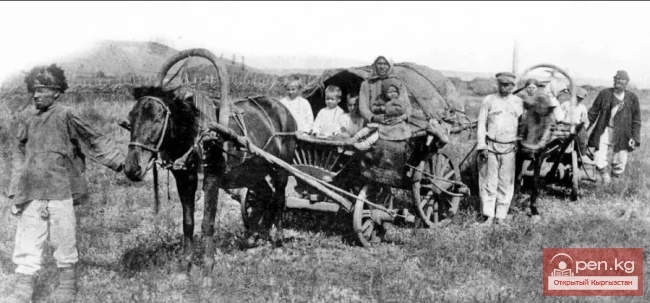

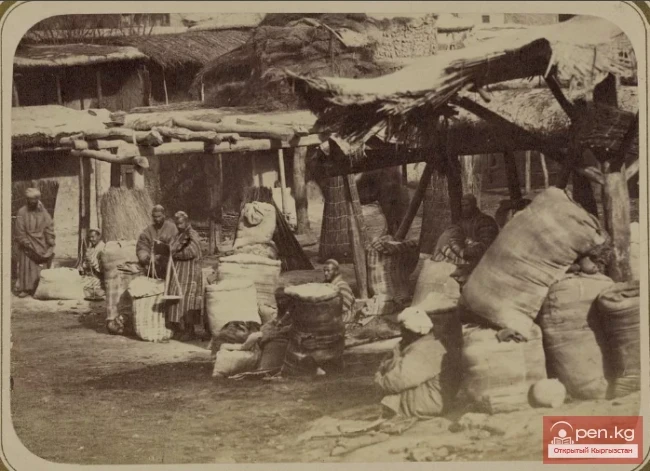

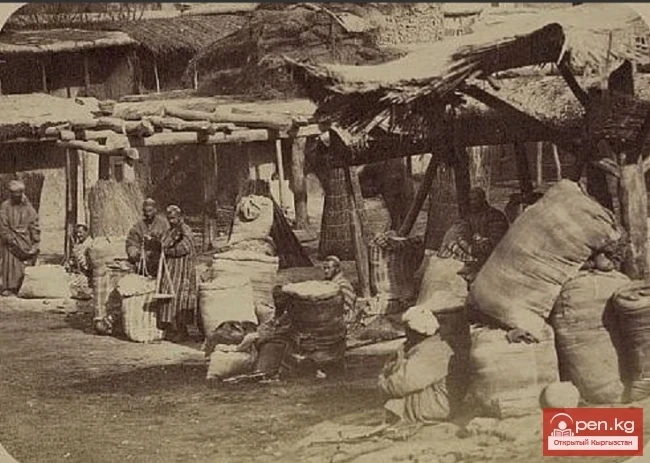

The nature of the economic activities of the urban residents at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century can be judged by their sources of income. Thus, out of 34.2 thousand Osh residents in 1897, for 17.7 thousand city dwellers, agriculture was the main occupation, for 8 thousand it was artisanal crafts, and for 4.6 thousand people, it was trade. The incorporation of southern Kyrgyzstan into Russia had a favorable effect on the development of trade in Osh, which reached several million rubles in annual turnover at the beginning of the 20th century. At the largest market in the region, the Osh bazaar, livestock, grain, and other agricultural products brought by Kyrgyz and Russian peasants were exchanged for manufactured goods and other factory products. Alongside market trading, stationary trade also developed significantly, with the number of points exceeding a thousand at the beginning of the 20th century.

The city of Osh played a significant role in trade with Semirechye, Fergana, and other regions of Central Asia, as well as in external (transit) trade with eastern countries. In Osh, one could purchase not only local handicrafts and products of Russian industry but also various goods from Kashgar, Afghanistan, and India.

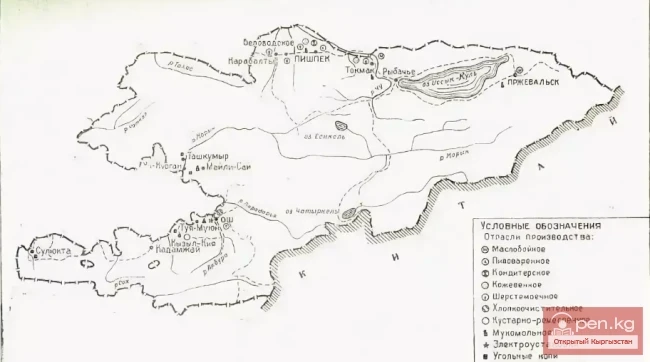

Being the largest city in Kyrgyzstan by population and trade development, Osh significantly lagged behind in industrial terms compared to Pishpek, Przhevalsk, and especially Fergana. In 1913, Osh had an electric power station, a mill, oil extraction, and brewing plants (Orlova and Moneta), and numerous artisanal workshops producing carpets, embroidery, footwear, clothing, etc. In 1913, only 25 hired workers were employed at four relatively large enterprises in Osh, which produced goods worth about 30 thousand rubles per year. "Due to the insignificant importance of Osh, it may not be considered as an industrial point..." wrote pre-revolutionary authors in their studies of the industry of Turkestan. However, the number of various artisanal establishments in Osh was quite significant. In 1914, there were 369 rice husking mills and 490 oil extraction facilities of "native type." Osh was an important center of crafts and artisanal production in Southern Kyrgyzstan.

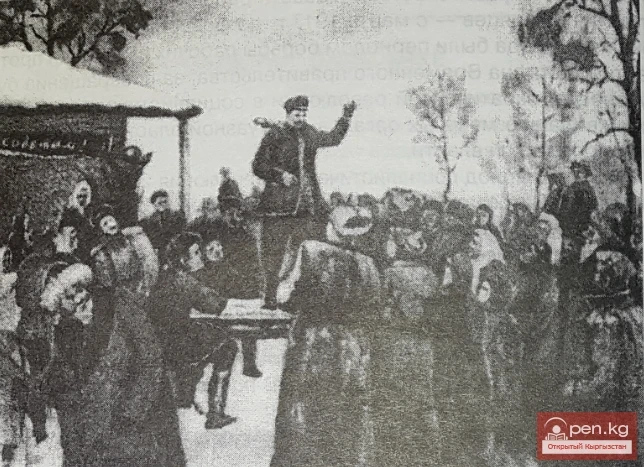

Qualitative Transformation of the Old Khan's Osh