By including "Kremlin Chimes" by N. Pogodin in its repertoire, the theater took on a very responsible commitment. The image of Lenin, captured through the means of art and theater, is a powerful ideological weapon in the hands of the party. Its impact and influence on the people are limitless. To learn from Lenin, to follow his precepts in everything—this is the aspiration of every communist, every Soviet person. There is no higher, no more honorable task for a writer, artist, or actor than the work of recreating the image of the leader of the socialist revolution.

At the center of the play "Kremlin Chimes" is V. I. Lenin. His words and actions determine the entire development of the plot; all narrative lines lead to him. Unlike his previous works, here N. Pogodin seeks to reveal Lenin's character through his connections with people. The playwright abandoned the "quotational" method, where the role is constructed from fragments of his published speeches and works. His task was to move away from historical chronicle, blindly following the facts, and to create a poetically generalized image of the leader. This is a correct and very fruitful path, for only in this way can one approach the portrayal of the most human of people. However, this is also much more difficult.

"Kremlin Chimes" is a play about Lenin. But at the same time, it is also a play about the era, about the stormy years of the civil war. The ensemble had to recreate the color of the era, to make the audience feel the uniqueness of those unforgettable days. The theater approached the work on the play with great excitement. It truly required the tension of all creative forces to convey to the audience both the greatness of Lenin's simplicity and the grandeur of the era. Only when the thunderous applause resounded from the audience on the premiere day did the ensemble believe that their work was not in vain.

The curtain rises—we are in Lenin's office. In the hall—applause. The audience seems to have entered a familiar office from dozens of photographs and seen a living Lenin. No, it is not the portrait and photographic resemblance that the audience applauds at this moment. They have been transported into the very atmosphere of that time and are grateful for this magic to the theater.

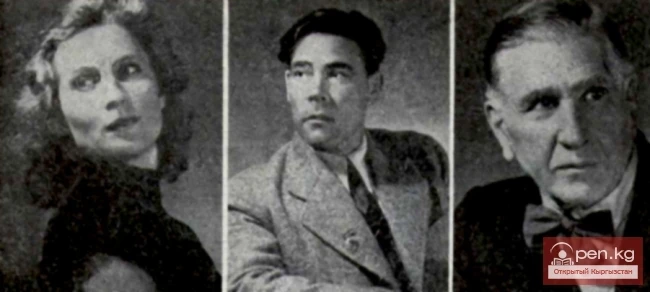

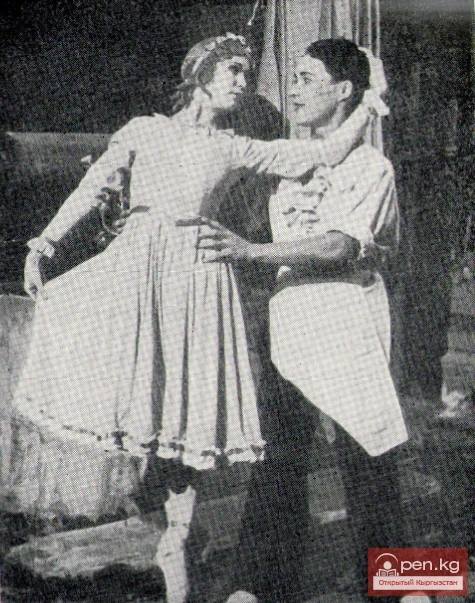

Of course, to achieve perfect portrait resemblance and an accurate reproduction of Lenin's speech required very complex and patient work. How many times the wig was changed and adjusted, how many tiny details in the makeup were sought, how much time the People's Artist of the Kyrgyz SSR V. F. Kazakov rehearsed Lenin's speech. All of this was finally found—the appearance, the gait, and the gestures became organic; the actor ceased to notice them, he merged with the image.

But in the end, this turned out to be a secondary matter. The recreation of external features was only one means of achieving the main goal. It was much more difficult to solve the tasks of a larger scale—to show Lenin as the leader of the revolution, the head of a great country. Copying external traits here was almost of no help. The actor had to feel the era every minute, to correctly understand the people around him, to comprehend the role of the leader of the party and the state at that immeasurably difficult moment in the history of Soviet Russia.

The success of V. F. Kazakov is explained precisely by this. By not emphasizing the peculiarities of appearance and speech, V. F. Kazakov managed to convey the main thing—the simplicity and charm of the leader, the continuous work of his thought, the burning of his indomitable temperament.

Perhaps the most powerful impression is made by the scene on the boulevard. On a dark, pitch-black night, seemingly symbolizing the incredibly difficult position of the young Soviet state, Vladimir Ilyich walks with his young friend, sailor Rybakov, through the Moscow boulevards. A lyrical conversation about dreams, about love. A meeting with workers. A conversation with them—and Lenin is inspired. Thousands of thoughts again engulf him. Here, in the impenetrable Moscow night, thoughts about electrification are born. And the strength of the actor's penetration into the role is such that we almost visually feel the work of Lenin's thought. Yes, this is how great ideas were born!—the audience will say.

It is from such episodes, stroke by stroke, that the image of Lenin is formed and grows. Throughout the play, we live together with Lenin, perceive all the events through his eyes, and observe the state activities of the great organizer of the Communist Party.

In Soviet art, there are many excellent examples of work on the image of Lenin. V. Kazakov does not take the easy path of imitation. He creates his own Lenin, and his image coincides so much with ours, with what everyone carries in their heart, that we do not separate the actor from the image of the leader on stage.

It cannot be said that the work on "Kremlin Chimes" went completely smoothly. The director and the ensemble did not immediately achieve true ensemble performance in the play. The public and the ensemble were particularly dissatisfied with the first scene—"At the Iver Gate." The atmosphere of the time did not come across; the world of random people, speculators, and swindlers was not shown with the necessary brightness. As a result, not everything was clear in the further course of the play. The theater's management decided on a decisive overhaul of this very important scene, meticulously striving for the refinement of each episodic role. Only after this did the scene improve.

Alongside V. Kazakov, the People's Artist of the Kyrgyz SSR A. Kuleshov achieved undeniable success. His Zabelin—a powerful, willful man of great and unique intellect—evokes deep sympathy from the audience. His excellent posture, gait, and deeply concentrated gaze—all of this is done subtly, firmly, and impressively.

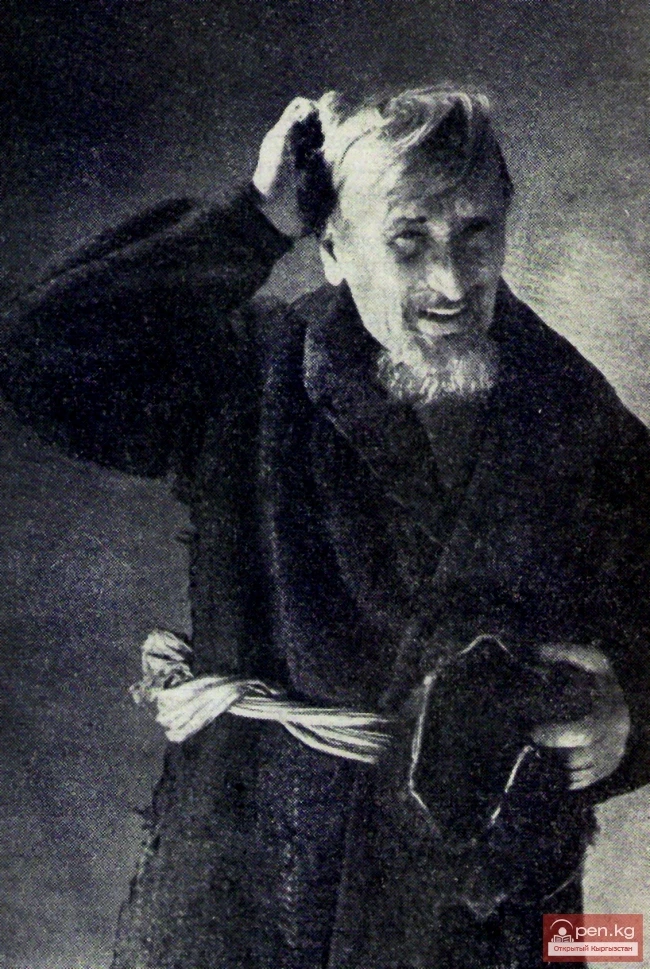

Against the backdrop of the numerous characters in N. Pogodin's play, the watchmaker (artist L. Yasinovsky) stands out particularly. The artist managed to completely captivate the audience, even though Lenin was nearby on stage. The watchmaker is wise; he, an ordinary witness to grand historical events, understands the greatest historical significance of what is happening correctly, truly philosophically (unlike Zabelin). He is the only watchmaker in the world who has the fortune to make the Kremlin chimes play the "Internationale." The title of the play becomes a symbol precisely after the dialogue between Lenin and the watchmaker. And L. Yasinovsky, without pressure, without cheap tricks, shows the heart and mind of this small, but in reality, great man.