Early Repertoire of the Ch. T. Aitmatov Russian Drama Theater

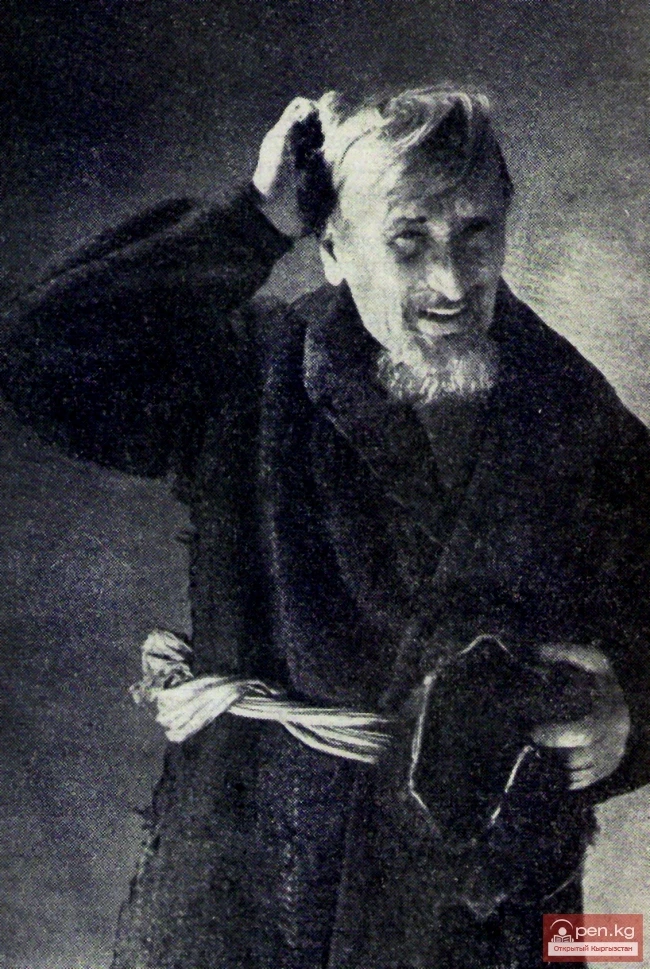

Honored Artist E. V. Zhenin — Kazanok. "Kremlin Chimes"

The repertoire is a mirror of the theater. It is the repertoire that defines the very character of the creative team's work. The choice of dramatic works depends on the creative aspirations of the directors and actors, on that elusive concept that constitutes the face of the theater troupe. One can judge by the repertoire how bold the collective is, whether it aims for well-played and long-known plays or takes on untested novelties.

The resolution of the Central Committee of the VKP(b) "On the Repertoire of Dramatic Theaters" (1948) provided clear guidance for all theaters in our country. Proximity to the people, to modernity, the ability to respond to the most pressing issues of today with their creativity — this is what the party expected from the figures of theatrical art. The latest party documents — N. S. Khrushchev's speech "For a close connection of literature and art with the life of the people" and the resolution of the Central Committee of the CPSU "On correcting mistakes in the assessment of the operas 'Great Friendship' by Muradeli, 'Bogdan Khmelnitsky' by Dankevich, and 'From the Bottom of My Heart' by Zhukovsky" — show how attentively the party monitored the development of art and how it nurtured the cadres of Soviet art figures.

The aspiration to fully embody contemporary themes on stage, to truly become closer to the people defined the theater's repertoire plans.

Today's repertoire of the Russian State Drama Theater named after Ch. T. Aitmatov includes the best works currently available from modern playwrights. The theater eagerly seeks good new plays, and its portfolio invariably contains dozens of new works waiting for their stage embodiment.

Before moving on to a more detailed characterization of this aspect of the collective's activity, it is necessary to focus on the most important feature of the work of the Russian theater in the national republic. From the very first years of its existence, the theater named after Ch. T. Aitmatov sought to master the best works of Kyrgyz dramaturgy. This is natural. Where, if not in a Russian collective, should a full-fledged play by a Kyrgyz writer receive a long stage life? Such a production closely familiarizes the Russian audience with the art and life of the fraternal people and, at the same time, integrates national dramaturgy into the broader context of literature. This is the mutual enrichment that underlies the construction of the entire multinational culture of the Kyrgyz people.

It cannot be said that the theater fully fulfills this very important mission. The number of Kyrgyz works in the repertoire has been small in recent years.

A significant role in mastering the Kyrgyz theme was played by G. Kandel's play "Love." The author is not Kyrgyz, but he lived in the republic for many years and studied the life and history of the people well enough.

This drama tells the story of a young Kyrgyz woman, about true and false love, about unshakeable principles of morality and the corrupting influence of old customs.

"Love," as it appeared on the theater stage, could not be regarded as a fully completed work. Lengthy scenes, which added little to the development of the characters, burdened it and complicated the audience's perception of the drama. Careful work on the text of the play was necessary. The theater undertook this, remembering the value of the essentials: living characters, life conflicts, and good language. Together with director N. A. Belyakov, the author thoroughly "cleaned up" the drama: he removed unnecessary scenes that slowed the development of the conflict and clarified the characters' traits.

The play appeared on stage. The audience warmly accepted it; the characters in "Love" easily resembled familiar people encountered in real life. The author managed to preserve the uniqueness of the national color; the Russian actors did not appear to be costumed but truthfully conveyed the characteristics of the people of Kyrgyzstan.

This can primarily be said about T. Varnavskikh, who played the role of Guljan — the image of a pure and strong woman who has earned the right to universal respect. She denies her husband's right to arbitrariness and contempt towards her. She grows before our eyes from a modest, loving girl into a true daughter of Soviet Kyrgyzstan. Guljan is an artist. She rightly thinks about her high calling.

The husband and his relatives try to hold the young artist back, to lead her away from the great path. Guljan's struggle with them for her right to creativity, for her bright path constitutes the central conflict of the play.

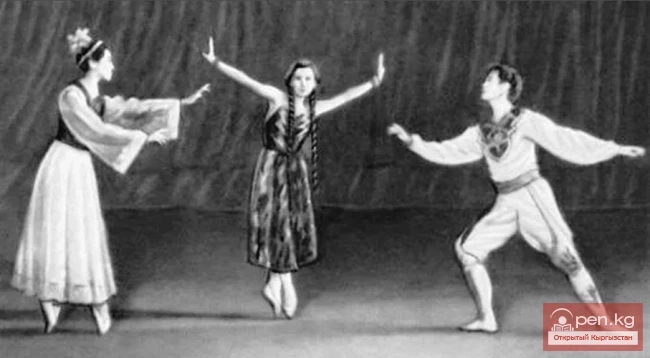

In 1958, the theater turned to the play "Sarynjy" by K. Eshmambetov, adapted by V. Vinnikov. What, in fact, prompted such a choice?

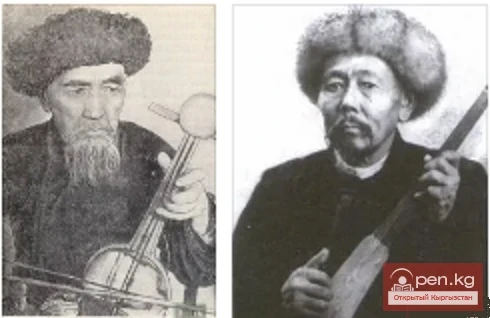

The inexhaustible wealth of Kyrgyz epic is well known. Folk singers — yrchis and akyns, as well as special storytellers of "Manas" — manaschi sing epic works composed many centuries ago for hours on end. It is quite natural that K. Eshmambetov, in search of a plot, turned to the treasure trove of folk creativity. The epic "Sarynjy" offers remarkable opportunities for creating a monumental folk drama.

It should be noted that the first version of "Sarynjy," which appeared in the 1930s, could not be classified as this genre. The tragedy of Sarynjy, the "Kyrgyz Hamlet," through the intricate web of vile intrigues bearing the high and bright, was reduced to the vicissitudes of a family drama. The struggle for the khan's throne, for a woman, became the center, while social motives were veiled.

The drama of K. Eshmambetov sounded differently. The author, together with the theater, reworked it anew and found a new version of the central conflict. Sarynjy now became much more an embodiment of everything new, bright, and progressive, while his enemies symbolized the dark forces of the past. Not the struggle for power, but the struggle for a better future for the people became the foundation of the stage action. The author elevated the drama to the heights of broad generalizations.

And in the high epic style of the legendary storyteller, the words of the finale resonate:

Yes, it was so and will be so, my son!

About what delights us and troubles us,

Someday a truthful tale will be woven

For the great-grandchildren at the akyn's celebration.

And that tale of the descendants, perhaps,

Will teach us to see life even clearer,

To hate enemies even more fiercely,

To love friends even more strongly.

Thus, the voices of distant ancestors resonate with modernity. The author found the correct correlation between the ancient legend, proclaiming "high humanitarian ideals," and living modernity.

At the same time, the collaborative work on the text led to the language of the drama becoming clearer and more concise. The number of characters decreased, and unnecessary episodes that cluttered the development of events disappeared.

Actress T.P. Artamonova as Stepanida. "The Merchants"

The theater perceived the new version of the play "Sarynjy" as a folk drama. The cunning and hypocrisy of Bokoya, Konura, and Jamake are contrasted with the honesty and courage of Sarynjy's friends, who help him overcome his enemies. The key to the new understanding of the drama is given by the words of Sarynjy's father — Jamgyrchi — before his death, addressed to his son:

Do not boast of your generosity, do not lie

And grasp your neighbor's hand with your own,

Do not force your friend to be a servant

And do not replace him with a servant,

Learn to earn the love of the people,

So that before you it rises like a wall,

As it stood before me for ten years, —

Then, my son, you will live in happiness.

In the finale, the people themselves deliver a verdict to the traitors and call Sarynjy to power.

The theater correctly understood the drama, its romantic coloring, its high humanitarian ideals, its excitement. It should be noted that the very development of the action, the abundance of unexpected dramatic turns, the author's ability to maintain tension, coherence, and completeness of the composition make "Sarynjy" a notable phenomenon not only in Kyrgyz dramaturgy. Let us add to this the sonorous and smooth verse of the translation, which excellently reproduces the features of Kyrgyz versification. V. Vinnikov not only translated well but also enriched the original in many ways.

In working on the staging of this work, the theater had to overcome a number of difficulties. The greatest of these was creating a national color. It is not only a matter of the ethnographic accuracy of costumes and settings, the actors' ability to adopt the mannerisms, observe customs on stage, etc. It was important to reproduce the very spirit of the era and the people on stage, for the actors to temporarily become true Kyrgyz.

Some experience in this direction existed — the work on "Love" by G. Kandel posed similar tasks. But it is one thing to show the audience a modern mechanizer Arstan, and another thing to portray the legendary khan Jamgyrchi. Director M. Malamud, artist I. Belevich, costume designers, makeup artists, prop masters, and most of all, the actors had to work very hard to recreate the images of a distant past.

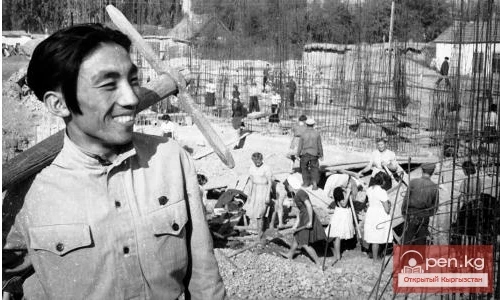

The tasks of the collective looked completely different when staging another play by a Kyrgyz playwright — the comedy "Light in the Valley" ("My Ail") by R. Shukurbekov in the translation of A. Davidson. If "Sarynjy" features high passions and a tragic intertwining of events, then "Light in the Valley" transports the audience to the bright atmosphere of the ail. The comedy is simple, somewhat naive, but the freshness and immediacy of the characters, the charm of youth are captivating. The author knows the village well and managed to convincingly portray the people of modern Kyrgyzstan.

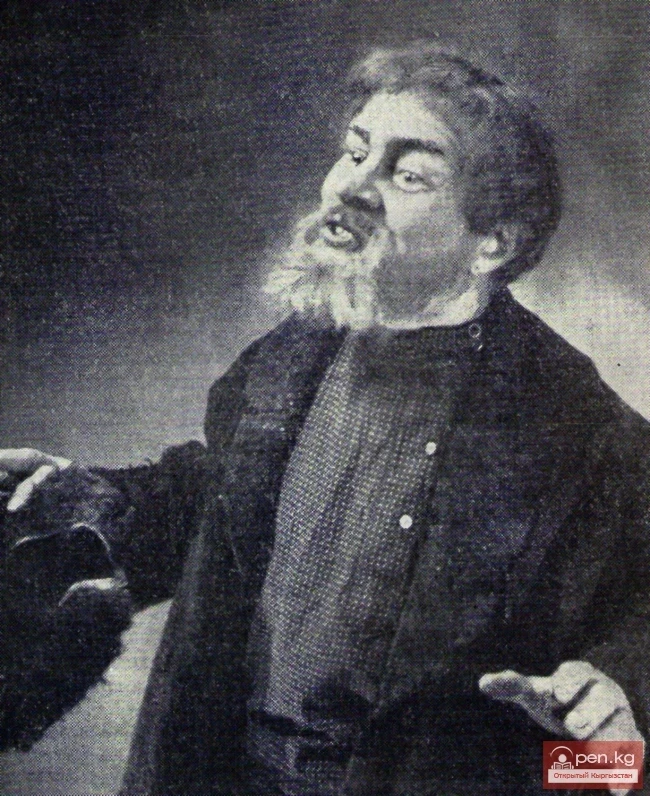

Actor M.K. Pravov as Perchikhin. "The Merchants"

With a smile, we follow the tangled incidents that prevent the lovers from uniting, the troubles that pursue the lazy and idle Rysbek. Some of this comes from vaudeville; the situations in which the hero finds himself at the author's will are not so new. One can debate the supposed "conflict-free" nature of the comedy. But the author achieved the main thing - the images of the people of today's Kyrgyzstan. The image of the young brigade leader Saadat is particularly interesting. The great purity and charm of Saadat, her indomitable energy, inventiveness — how close these traits are to many thousands of such Saadats, the girls of Kyrgyz villages and ails.

Director V. Molchanov and the entire creative team accepted "Light in the Valley" as a lyrical comedy, allowing them to tell about our contemporaries. Bright, festive tones dominate both the design of the performance and the manner of the actors' play. The performance is cheerful, full of optimism.

In the process of preparing the performance, the theater, together with the author and translator, worked thoroughly on the text of the play. The task was clear: to emphasize the theme of labor, to show more fully and deeply the formation of the personality of a young Kyrgyz girl.

Thus, Kyrgyz plays appear in the current repertoire of the theater. Work with local authors continues. K. Eshmambetov and R. Shukurbekov have gained much from the creative collaboration with the Russian theater collective; communication with experienced masters of the stage has helped them master dramatic technique, dialogue mastery, etc. In turn, many Kyrgyz figures of art have come to the aid of the Russian collective to reproduce the life and customs of the Kyrgyz people on stage with the greatest proximity to life’s truth. And here the process of mutual enrichment, so characteristic of the history of theatrical art in Kyrgyzstan, has manifested itself.

Read also:

The Best of Foreign Drama

Cultural contacts with the countries of people's democracy and the West have become...

Repertoire for March 2015 of the Russian Drama Theater named after Ch. Aitmatov

March 7, Saturday. 11:00 Fairy tale "Ivan and Marya," Vladimir Goldfeld 18:00 Comedy...

Russian State Drama Theatre named after Chinghiz Torekulovich Aitmatov

In the evening, the capital of Kyrgyzstan is especially beautiful. Bright rays of streetlights...

Theaters of the City of Osh

Uzbek Musical and Dramatic Theater The city has notable achievements in the field of theatrical...

Organization in Frunze of the Kyrgyz State Drama Theater. Document No. 129 (June 1941)

RESOLUTION OF THE COUNCIL OF PEOPLE'S COMMISSARS OF THE KYRGYZ SSR "ON THE ORGANIZATION...

Working on a Soviet Play

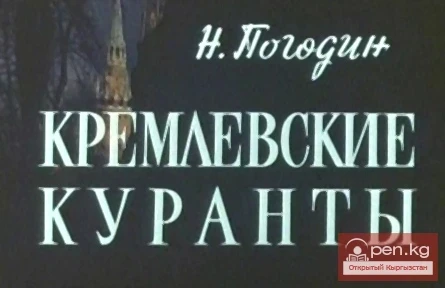

The choice of the "Kremlin Chimes" for the repertoire is quite understandable, although...

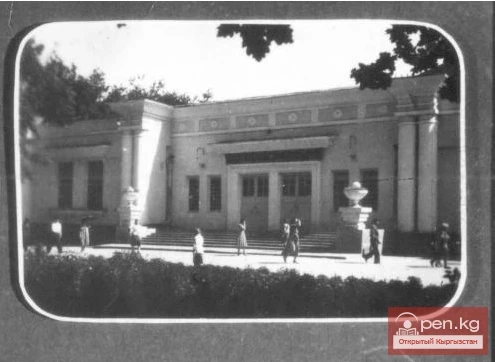

State National Russian Drama Theater named after Ch. Aitmatov

Russian Drama Theater Named After Ch. Aitmatov In 1935, the Government of the Kyrgyz Soviet...

Organization of the Russian Drama Theater in the city of Frunze. Document No. 99. (July 1935)

RESOLUTION OF THE KIROBKOM OF THE VK (B) "ON THE ORGANIZATION OF THE RUSSIAN DRAMA THEATER IN...

Repertoire for April 2015 of the Kyrgyz National Academic Theater of Opera and Ballet named after Abdylas Maldybaev

REPERTOIRE for April 2015...

Kyrgyz State Puppet Theatre named after M. Zhangaziev

The puppet theater in Kyrgyzstan was established for the first time in 1938. For a long time,...

"Raymonda" ballet by A. Glazunov, featuring People's Artist of the Russian Federation prima ballerina of the Bolshoi Theatre Maria Allash

On September 28, Sunday, at 17:00, the Kyrgyz State Opera and Ballet Theatre will present the...

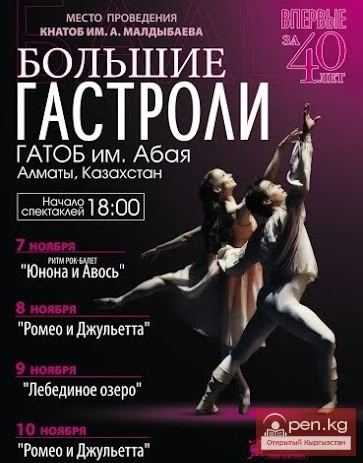

The Kazakh State Academic Theater of Opera and Ballet named after Abai will perform in Bishkek.

For the first time in 40 years, from November 7 to 10, 2014, the Kazakh State Academic Theater of...

The performance "Kremlin Chimes"

By including "Kremlin Chimes" by N. Pogodin in its repertoire, the theater took on a...

Repertoire for March 2015 of the Kyrgyz National Academic Theatre of Opera and Ballet named after Abdylas Maldybaev

March 5, Thursday 18:00 The Public Fund for the Creativity of Children and Adolescents and the...

Issyk-Kul Regional Musical and Drama Theater named after Djantoshev

The Issyk-Kul Regional Musical and Drama Theater named after K. Jantoshov is currently the only...

Further Paths for the Development of Kyrgyz Theater. Document No. 108 (December 1936)

RESOLUTION OF THE KIRGIZ REGIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE VKP (b) "ON THE FURTHER PATHS OF...

Working with the Collective of the Russian Drama Theater named after Krupskaya during the Soviet Period

O.V. Popova, K.Ya. Ivanov, I.K. Tkachuk Regular classes were organized for all young, mostly...

Kyrgyz State Youth and Children's Theater named after B. Kydykeeva

When was the Kyrgyz Youth Theater created? The Kyrgyz Youth Theater was established in the late...

Stoffer Yakov Zinovievich

Shtoffer Yakov Zinovievich Theater artist. Honored Artist of the Kyrgyz SSR. The name of Y....

The II International Small Forms Theater Festival "Impulse" will open in Kyrgyzstan.

Preparations are underway in Bishkek for the II International Theater Festival of Small Forms...

Belkin Georgy Ivanovich

Belkin Georgy Ivanovich Theater artist. People's Artist of the Kyrgyz Republic. Born on...

Actors of the Russian Drama Theater of the Kyrgyz SSR

Actors of the Russian Drama Theater of the Kirghiz SSR: L. V. Nelskaya, V. N. Dostovalov, I. A....

Night at the Theater

On May 24, from 18:00 to 00:30, the State National Russian Drama Theatre named after Ch. Aitmatov...

Kyrgyz National Academic Drama Theatre named after T. Abdumomunov

National Academic Drama Theater named after Toktobolot Abdumomunov By the decision of the Central...

Sharsen Termechikov (1896—1942)

Sharshen Termechikov (1896—1942) — a popular comic-satirist, honored artist of the Kyrgyz SSR,...

Soloists of the Bolshoi Theatre will perform on the stage of the M. Maldybaev Opera and Ballet Theatre.

At the Kyrgyz National Academic Theatre of Opera and Ballet named after A. Maldybaev, preparations...

Organization of a Puppet Theater in the City of Frunze. Document No. 123 (September 1939)

RESOLUTION OF THE COUNCIL OF PEOPLE'S COMMISSARS OF THE KYRGYZ SSR "ON THE ORGANIZATION...

Nurmataov Yuldash Sherovich

Nurmatov Yuldash Sherovich Theater artist, Honored Worker of Culture of the Kyrgyz Republic. Born...

The Russian Drama Theater Celebrates Its 80th Anniversary

On that evening, all performances were canceled. On December 12, all admirers of theatrical art...

The Ministry of Labor selects the best works for the Chingiz Aitmatov Award.

The Ministry of Labor, Migration and Youth is conducting a selection of works for the State Youth...

XII Annual Republican Festival of Children's and School Theaters of Kyrgyzstan

From March 25 to 28, 2015, Bishkek will host the XII Annual Republican Festival of Children's...

Organization of the First Kyrgyz Theater Studio

ON THE PATHS OF CREATING A NATIONAL BALLET After October, the peoples of the former tsarist...

People's Artist of the Kyrgyz Republic Gulshara Dulatova

People's Artist of the KR Gulshara Dulatova was born in 1930 in Tokmok. She began her career...

Mastering the Foundations of Classicism in Kyrgyz Ballet

The First Steps Towards Professional Kyrgyz Ballet Folk dances, based on elements of rituals and...

Moldakhmatov Asanbek

Moldakhmatov Asanbek (1923-1993) Theater artist. Painter. Honored Artist of the Kyrgyz SSR. Born...

Mikhail Ivanovich Novikovsky

Mikhail Ivanovich Novikovsky Theater artist, Honored Artist of the RSFSR. Born on August 19, 1919,...

Osh Academic Musical and Dramatic Theater named after Babur

The dramatic circle in Osh first emerged in 1914. Its organizers were Beknazar Nazarov and...

Theater Scholar, Critic, Translator Avas Syrymbetov

Theater scholar, critic, translator A. Syrymbetov was born on August 22, 1936, in the village of...

Playwright Viktor Shvemberger

Dramatist V. Shvemberger was born on October 23, 1892—January 23, 1970, in the city of Stavropol...

Omuraliyev Baku

Omuraliyev Baky Film actor. Member of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union since 1968. Born on...

Russian Drama Theater named after Krupskaya in the Post-War Period

After the war, the theater troupe was joined by new actors. By this time (1945—1956), the core of...

The Theater of Kyrgyzstan in the 20s-80s

Before the Great October Revolution, the Kyrgyz did not have a national professional theater....

Such "Grooms"!

The State National Russian Drama Theater named after Chinghiz Aitmatov constantly delights art...

Bishkek City Drama Theater named after A. Umuraliyev

Bishkek City Dramatic Theater named after A. Umuraliev The Bishkek City Dramatic Theater named...

Resolution of the Central Election Commission of the Kyrgyz ASSR on the Awarding of Honorary Titles to Artists. Document No. 102 (December 1935)

RESOLUTION OF THE CENTRAL EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE OF THE KYRGYZ ASSR ON AWARDING HONORARY TITLES OF...

The Transition of the Kyrgyz Ballet Theater from Classical to Contemporary Repertoire

Difficulties in the Growth of a Young Theater In 1948, the theater thoughtfully prepared for the...

Theater of Shadows

From April 10 to April 30, 2014, the State Historical Museum of the Kyrgyz Republic will host an...