Prohibition of the Left Socialist-Revolutionary Party

It is a common belief that the beginning of the split between the Bolsheviks and the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries was marked by the latter's refusal to recognize the Treaty of Brest. In reality, the disagreements began even earlier. Two weeks after the October Revolution, a clash occurred over the closure of several bourgeois newspapers in Petrograd. The training of the Socialist-Revolutionaries let down the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries. They turned out to be more democratic than they would have liked and opposed the closures. Democratic values and principles were seen by them as an independent value, possessing not only tactical but also absolute significance. At a meeting of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee (VTsIK), the People's Commissar for Agriculture, Koligaev, spoke out against the closure of the newspapers, stating that his party does not view the issue of press freedom as a petty-bourgeois prejudice. Trotsky and Lenin opposed this, accusing the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries of ceasing to be socialists. A Bolshevik resolution passed by a margin of ten votes. Making a statement that the resolution on the press was a vivid and definite expression of a system of political terror and incitement of civil war, Proshyan called on all People's Commissars—Left Socialist-Revolutionaries to resign. The scandal was quelled at that time.

Another conflict occurred in December 1917, when the Bolsheviks issued a decree declaring the Cadet Party illegal. Proshyan again addressed the VTsIK in protest, wondering how it was possible to arrest deputies of the Constituent Assembly, who enjoyed immunity, and to ban a party without any accusations against it. But the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries were once again criticized for their insufficient revolutionary spirit, which they endured again.

The Left Socialist-Revolutionaries received another portion of criticism from Lenin when they opposed the official restoration of the death penalty.

In early 1918, they insisted on condemning the sailors who had independently killed two former ministers of the Provisional Government—Kokoshin and Shingarev—in a hospital, but the trial never took place.

These concessions, which the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries made in bits and pieces "in the name of the revolution," led to the situation by the summer of 1918 where the Bolshevik Party was no longer bound by any coalition, laws, democracy, or public opinion.

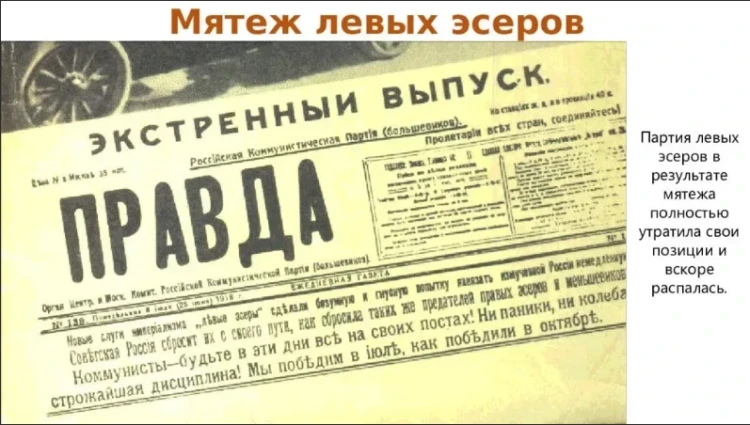

In July 1918, the Left Socialist-Revolutionary uprising was suppressed in Moscow. The ruling coalition of Left Socialist-Revolutionaries and Bolsheviks collapsed, unable to withstand the test of principle. The Left Socialist-Revolutionary Party was banned, and its leaders were arrested and sentenced.

This was the "swan song" of Russian populism as a revolutionary movement. The Bolsheviks achieved autocracy, which they had methodically and persistently pursued. Now, many new studies have been written about this uprising, shedding light on this tragedy from various perspectives. Some of them present irrefutable facts indicating that the uprising was initially and consciously provoked by the Bolsheviks, who began to grow weary of their restless and principled revolutionary comrades. The Left Socialist-Revolutionaries were also complicit in the actions of the Bolshevik Party. However, at least they had the courage to oppose the blatant injustices of the system being created. From the summer of 1918, the party was relentlessly attacked, and by 1922 it was completely eradicated through executions, imprisonments, and exiles. Since then, it was considered "self-dissolved."

Formation of the Socialist-Revolutionary Party (SRs)

Read also:

The First Attempt at Political Discrediting of A. Sydykov and the Left Socialist Revolutionary Movement in Turkestan

One episode from the life of A. Sydykov is associated with his membership in the Left...

Formation of the Socialist-Revolutionary Party (SRs)

The Socialist-Revolutionary Party (SRs) was formed in Russia in 1902 and made a loud statement...

Merger of the Left Socialist-Revolutionary Faction of the Semirechye Regional Soviet Congress with the Bolsheviks

The significant role of the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries in the fate of revolutionary Russia was...

The Masses of Semirechye for a Peaceful Evolutionary Path of Development

On November 12, 1917, elections in Semirechye for the Constituent Assembly were disrupted by armed...

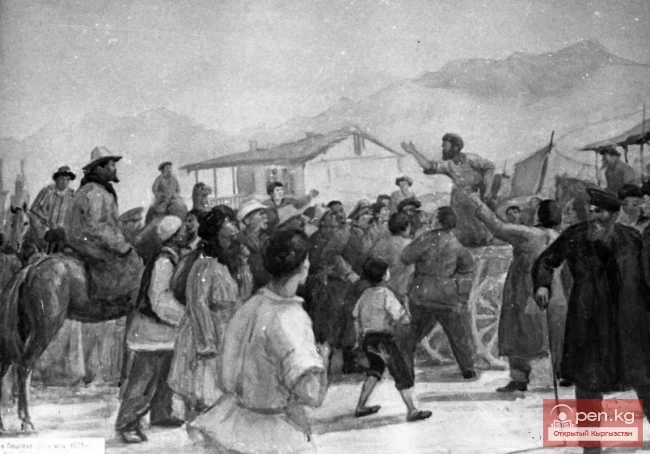

Suppression of the Rebellion in Pishpek

White Guard Armed Rebellion The strengthening of Soviet power deprived the bourgeoisie of any hope...

How the Political Case Against Abdulkarim Sydykov Was Fabricated

In the statement by X. Khasanov regarding the accused, it was written: "1. Citizen Abdulkarim...

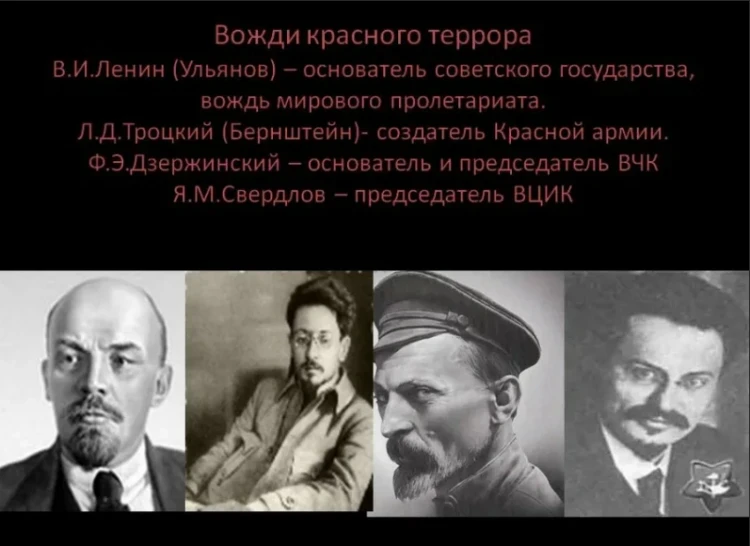

The Beginning of the Formation of the "Red Terror"

Upon coming to power, Lenin did everything to dismantle the old bourgeois legal system as a relic...

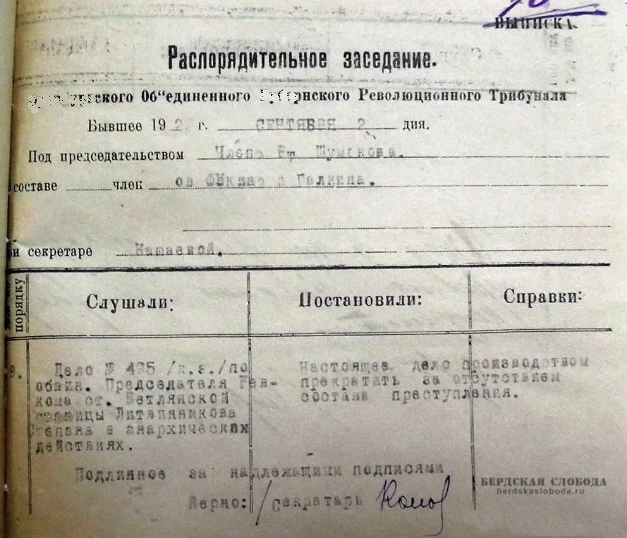

The Failure of the First Attempt to Deal with A. Sydykov

As a result of the investigation, a ruling by the revolutionary tribunal was issued, stating that...

"Red Terror" Against A. Sydykov

Two months before the spontaneously begun Belyvodsk uprising, on September 30, 1918, X. Khasanov,...

The Whirlwind of Revolutionary Events in Kyrgyzstan

The hastily assembled Soviet government clearly lacked people who were not just revolutionaries,...

Nikishev Petr Petrovich

Nikishov Petr Petrovich (1917), Doctor of Historical Sciences (1973) Russian. Born in the...

The closing ceremony of the World Nomad Games took place in Cholpon-Ata.

The solemn closing ceremony of the First World Nomad Games took place at the racetrack in...

U.S. Senate Fails to Pass Shutdown Prevention Bill for the 12th Time

The attempt by the U.S. Senate to approve a bill that would allow the government shutdown to end...

The USA announced sanctions against the companies "Rosneft" and "Lukoil"

U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent announced the introduction of new sanctions against two...

Seven Ejections and Tear Gas at the Match "Blooming" - "Bolivar"

The situation escalated at the end of the first half when a scuffle broke out between players,...

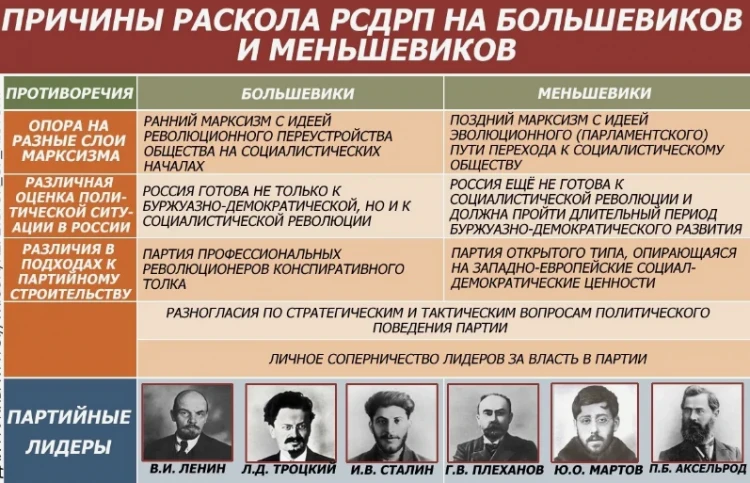

The Struggle of the Bolsheviks Against the SRs and Mensheviks for the Establishment of Soviet Power in Kyrgyzstan

The Soviets became local authorities that primarily influenced representatives of the European...

Preliminary Results of Voting in the 2015 Parliamentary Elections

After the polling stations close, the Central Commission for Elections and Referendums will...

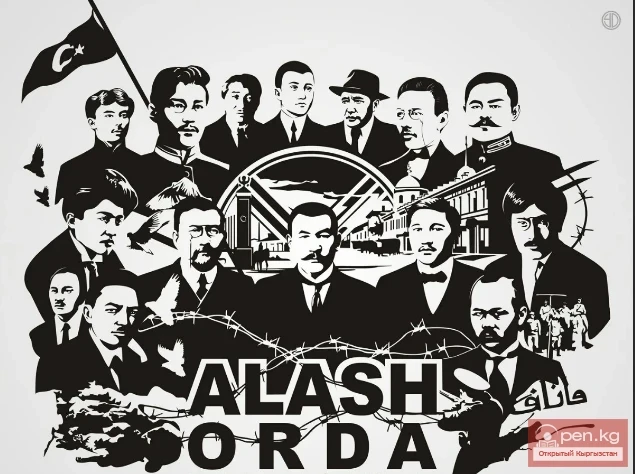

Legalization of the "Alash" Party after the Overthrow of the Tsarist Regime

The Alash Party and its leaders were accused of betraying the interests of their people in 1916,...

Gulzhigit Alykulov named Best Player of the Week in Asia

Footballer from Kyrgyzstan recognized as the best player of the week in Asia Midfielder of the...

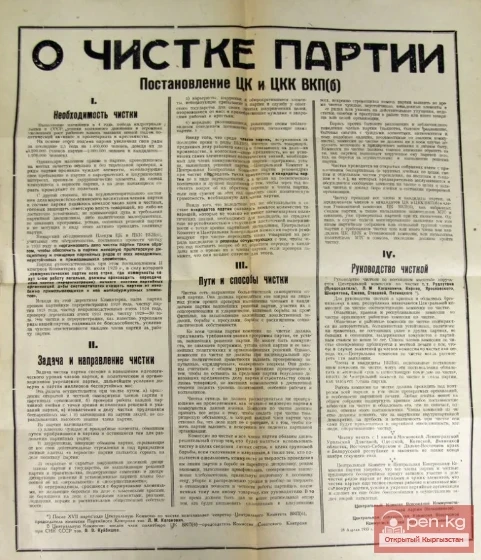

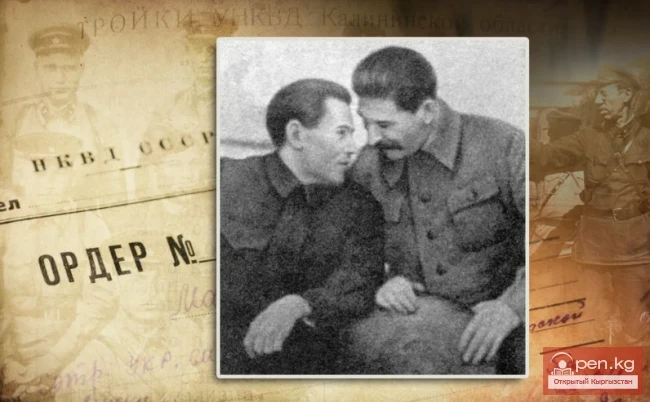

Exclusion from the Party and Arrest of Yu. Abdrakhmanov

Accusations of the Central Control Commission of the VKP(b) Against Abdrakhmanov On October 14,...

Pishpek - the Center of Revolutionary Struggle in the Chui Valley

The Beginning of the Recognition of Soviet Power in Pishpek and the District In the summer,...

Interesting Facts About the Sun

The speed of light in a vacuum is 299,792,458 m/s (≈300,000 km/s) We do not see the Sun; we see...

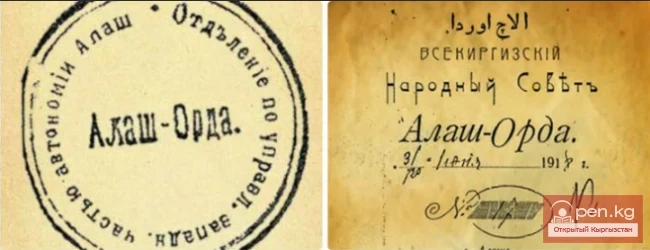

Establishment of the Pishpek Branch of the Kazakh-Kyrgyz Party "Alash-Orda"

Soon A. Sydykov resigned, as the Provisional Government disappointed the expectations of the...

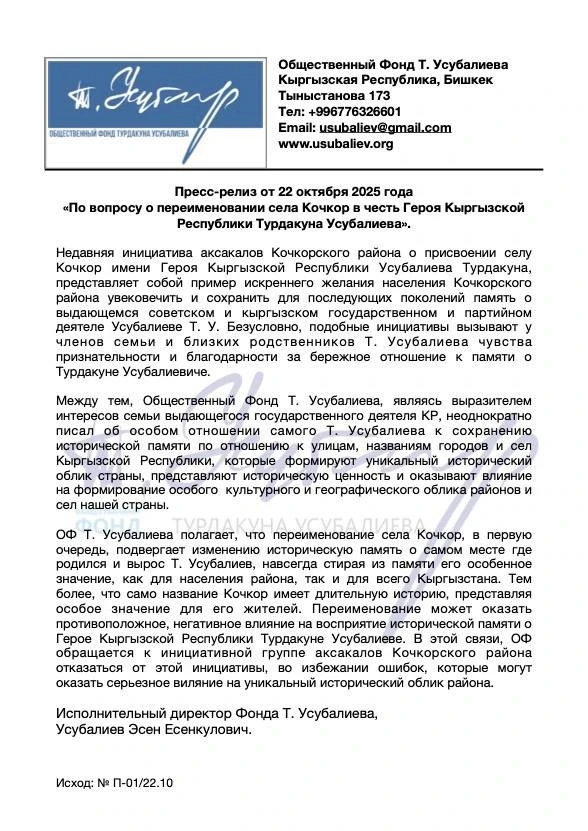

The Turdakun Usubaliev Family Against the Renaming of Kochkor in His Honor

The Turdakun Usubaliev Public Foundation has published an official statement regarding the...

Program of the Alash Party

A. Bukeykhanov, M. Tynyshpayev, Zh. Seydalin, M. Dulatov, and others played a significant role in...

Protocols of the Meetings of the New Authorities in June 1918 in the City of Pishpek. Documents No. 37 - No. 41

FROM THE PROTOCOL OF THE MEETING OF THE PISHPEK DISTRICT SOVIET ON THE NATIONALIZATION OF THE...

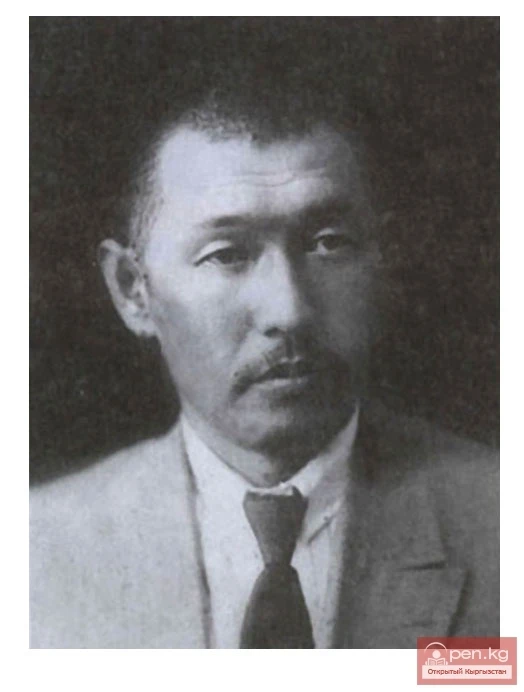

Sentencing of Tokchoro Joldoshev

Dzholdoshev and a number of other comrades were vilified at the V Plenary of the Kirgiz Regional...

"Punitive Operation Against the Rebel Workers in the City of Andijan"

Brutal actions of the punitive detachment against the rebelling Uzbek, Kyrgyz, Tajik, and Kipchak...

The future People's Commissar of Education of the Kirghiz ASSR, Tokchoro Joldoshev

“I AM A COMMUNIST!..”...

Communist Party, Komsomol, Trade Union of Soviet Kyrgyzstan

Development of Soviet Kyrgyzstan On October 14, 1924, the second session of the All-Russian...

Republic of El Salvador

SALVADOR. Republic of El Salvador A country in Central America on the Pacific Ocean coast. Area -...

Republic of Iceland

ICELAND. Republic of Iceland A country in Europe located on the island of the same name in the...

Mogul-Uzbek Forces Against the Kazakhs and Kyrgyz

The Murder of Abd ar-Rashid's Son. Mahmud ibn Wali and Shah-Mahmud Churas, authors of the...

Osh. Events in Southern Kyrgyzstan in February 1917

February Bourgeois-Democratic Revolution of 1917 in Osh. The overthrow of the tsarist autocracy on...

The Development of Printing in Kyrgyzstan in the Second Half of the 1920s.

At the beginning of 1925, together with the governing bodies of the Kyrgyz Autonomous Region, the...

A Man Reported Fraud by Car Dealership Employees. They Cannot Be Found

Takhir Tashirov, a resident of the village of Iskra in the Chuy region, demands that law...

"Theory" of Mass Organization by Yu. Abdrakhmanov

Disagreements between Kamensky and Abdrakhmanov In the early 1920s, Yu. Abdrakhmanov worked as the...

Erzhan Tokotaev did not concede a single goal in three matches of the AFC Champions League

The goalkeeper of the Kyrgyzstan national football team, Erjan Tokotaev, continues to impress in...

From the Kokand Fortress to the City of Frunze. The City of Frunze

CITY OF FRUNZE After the Great October Socialist Revolution, Kyrgyzstan was partially included in...

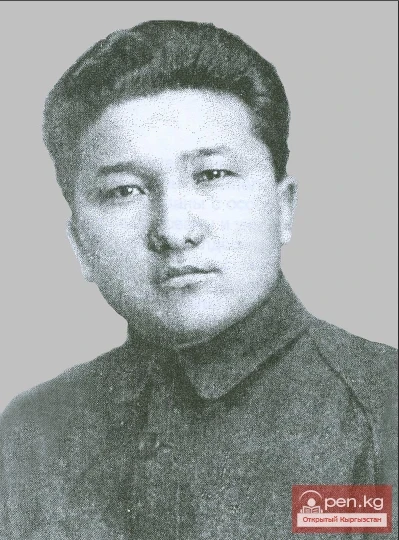

Abdykerim Sydyk uulu, Sydykov (1889 - 1938)

Abdykerim Sydyk uulu, Sydykov (1889 -1938) - one of the first Kyrgyz scholars who wrote works on...

Trump refused to approve the transfer of Tomahawk missiles to Ukraine after meeting with Zelensky

After the meeting, Zelensky noted that he and Trump discussed issues related to missiles but...

Historical Perspective of the Kyrgyz People under Soviet Power

The Achievement of Greatness by A. Sydykov Thanks to the Soviet System The fate of A. Sydykov and...

Kingdom of the Netherlands

NETHERLANDS. Kingdom of the Netherlands A country on the northern coast of Western Europe,...

The Printing and Book Publishing of Kyrgyzstan in the Soviet Period

The establishment of printing and book publishing in the republic was fraught with great...

The Beautiful Country Known as Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan is a small country bordering Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Russia. The main attractions...