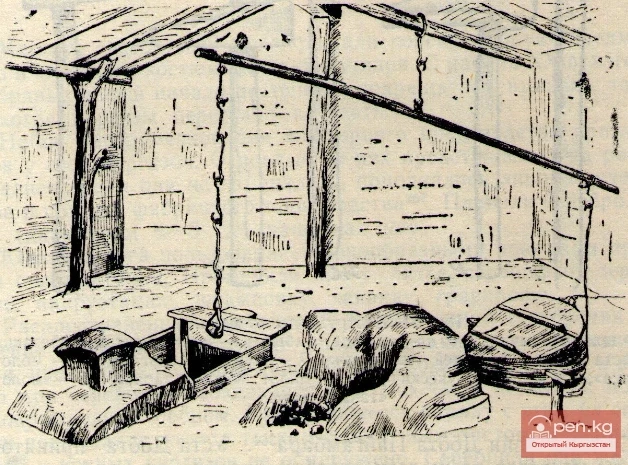

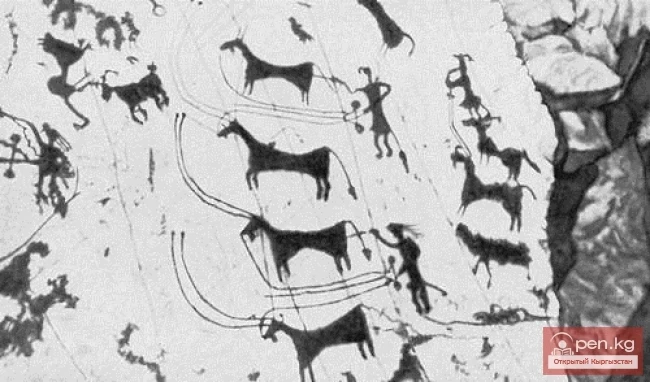

In the music for choor, sybyzgy, and other wind instruments, there is a special figurative sphere that is hard to imagine without in the national culture. It provides a sense of the eternity of existence and a mood of calm contemplation. Furthermore, wind instruments traditionally carry practical functions, serving the labor, daily life, and leisure of the Kyrgyz people. The oldest types of wind instruments, preserved to this day in certain samples, refer us to the "primordial music," the era of the birth of this art from natural sounds.

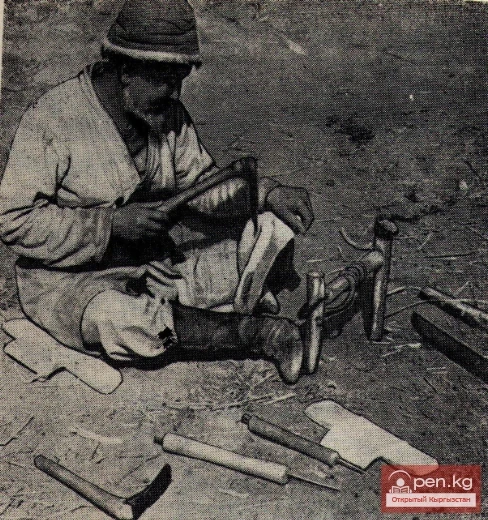

Nowadays, wind instruments are not as widely used compared to komuz, kyak, and temir komuz. The reasons include the lack of specialized workshops for their manufacture and professional schools for learning to play these instruments. Their mastery is mainly undertaken by performers of other instruments. However, in recent years, this area of instrumental culture has also been developing. Choor, chopo choor, chon choor, and sybyzgy have entered the repertoire of several folklore ensembles.

The repertoire of wind instruments includes kuyu-improvisations, based on a distinct, well-formed thematic "seed" that sprouts into a whole series of quite close variations. Almost all melodies for wind instruments have a monochromatic dramaturgy.

Since ancient times, choor and sybyzgy have been associated with the original activities of the Kyrgyz, with the harsh living and working conditions of shepherds (koychular). Perhaps that is why they still sound so mournful today: most kuyu are created in minor keys. These instruments, pastoral and lyrical-narrative by their very nature, were also quite simple in design and accessible for manufacture.

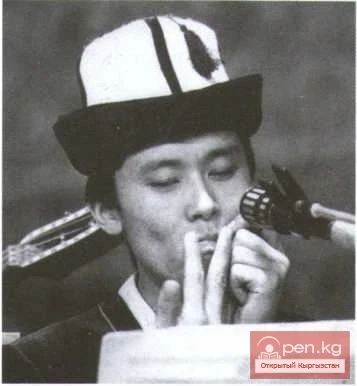

Playing certain types of choor is a labor-intensive process and therefore is a prerogative of men. The soft, somewhat nasal sounds of choor give the melodies a special color, in contrast to the sound of kerney, surnai, which are more powerful in volume and used in ceremonial situations—at holidays and public ceremonies.

The rich timbre of sybyzgy and less complex sound production (without a mouthpiece) allowed for a significant expansion of its repertoire—not only for practical but also for aesthetic purposes.

The melodies of the folk chopo choor are extremely concise and almost always anonymous. Modernized instruments of this group have acquired a small contemporary composer repertoire.

Kuyu for choor and sybyzgy have much in common with the intonational structure of speech and vocalization, as, firstly, the phrasing in them is determined by the characteristics of the performer's respiratory apparatus, and secondly, this is facilitated by the timbral properties and ranges of the instruments. Moreover, in achieving similarity with the human voice, the best choorchu have achieved impressive results. These instruments are also capable of producing various sound-imitation and sound-imitating effects.

Kuyu for choor and sybyzgy, as well as for other folk wind instruments, are poorly studied and almost not represented in notated form. For the first time, several pieces for these instruments were published in S. Subanaliev's study "Kyrgyz Musical Instruments" (Frunze, 1986).

Below is an analysis of several typical pieces for various types of choor and sybyzgy from the gramophone "Anthology of Kyrgyz Kuyu," based on the notated transcriptions by K. Dyushaliev.

"The Lament of Chiybula's Daughter" ("Chiybyldyn kyzy's Koshogu")—a kuyu for chogoyno-choor. The very title indicates the connection of this instrumental piece with vocal genres of Kyrgyz music, namely with "koshok"—the lament of a girl for her father. Therefore, the syntactic structure of the kuyu theme is subordinated to the norms of poetic text of lamentation. In each melodic construction, one can easily discern an eight-syllable line. However, the melody is significantly complicated instrumentally due to rhythmic combinations that reproduce the presumed intonations of the text's syllables.

The form of the kuyu is also typical for many genres of both instrumental and vocal music—repetitive-variant development of the main thematic core.

The kuyu "Akmaktym" (a female name) is recorded in performance on sybyzgy. The content of this kuyu embodies imagery typical for folk wind music in general. It has a palpable lyrical essence, a romantic spirit. It is a kind of instrumental "arman-dastan."

The piece is based on the well-known Kyrgyz folk poem "Baatyr Bekarstaan" ("Bekarstaan taychy"), in which one of the main characters is the girl Akmaktym. As an oral musical-poetic work, "Bekarstaan taychy" originally arose and spread widely in southern Kyrgyzstan. Then, with the development of interregional ties, the dastan also appeared in the repertoire of northern Kyrgyz storytellers.

The dastan exists in several variants, both in vocal and instrumental genres. Here is one of the instrumental variants of the dastan, more precisely, its part dedicated to the image of the heroine—the kuyu "Akmaktym." The melody is based on melodic variation of a relatively large initial construction. There are seven such variants. The basis of the modal organization of the presented sample is a five-step scale that fits within the range of a tritone. The sounds re-bemol and do consistently cadences the variant phrases of the kuyu.

And finally, a piece for brass choor "Kuyu of the Shepherd" ("Koychunun kuusu").

This kuyu is characterized by calm narrative and emotional restraint. In the imagination, a picture of picturesque Kyrgyz nature arises, and the melody of the shepherd seems to dissolve in the boundless space like a musical echo.

The form of the kuyu consists of five whimsically improvisational variants of the initial melodic phrase. The registral variation is achieved by shifting the melody up an octave. New intricate rhythmic details are introduced, enriching the theme.

The melody of "Koychunun kuusu" in modal terms represents a Phrygian pentachord B. The rhythm is characterized by activity, and various articulations, including forshlag, staccato, and harmonics, contribute to the articulation. Nevertheless, the prolonged intonations remind one of elements of lyrical genres "sekhetbay" and "kuygon," in which folk singers introduce exclamations and interjections like "ey" and "oy."

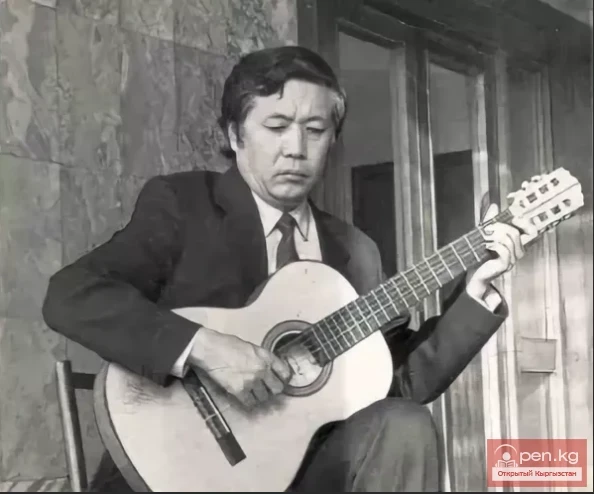

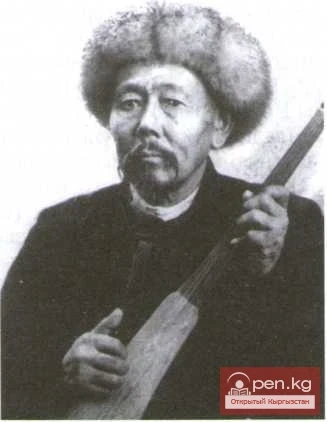

In the 20th century, the performing mastery is celebrated by Rayimberdi Sakeev (sybyzgy), Manat Kalzhigitov (baltyrkan choor), Subanaly Kalchoroev (yshkyrik choor, kamysh surnai), Junusaly Kuttubaev, Toykojo Buchukov (surnai), Asanbay Karimov (choor), and others. As a rule, each major performer possesses the secrets of making musical instruments.