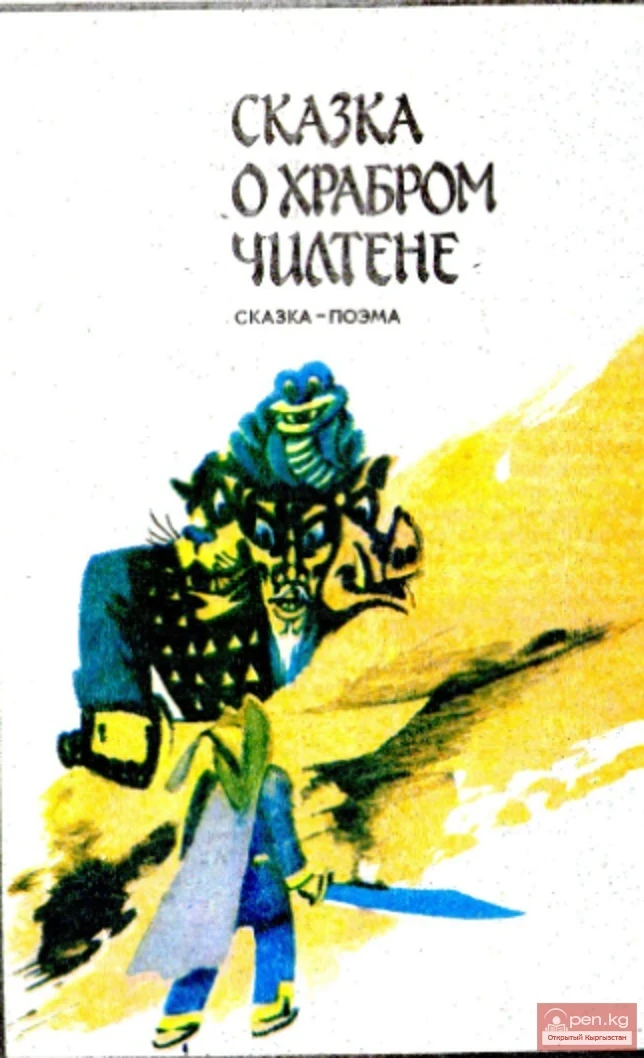

The Tale of the Wise Boy

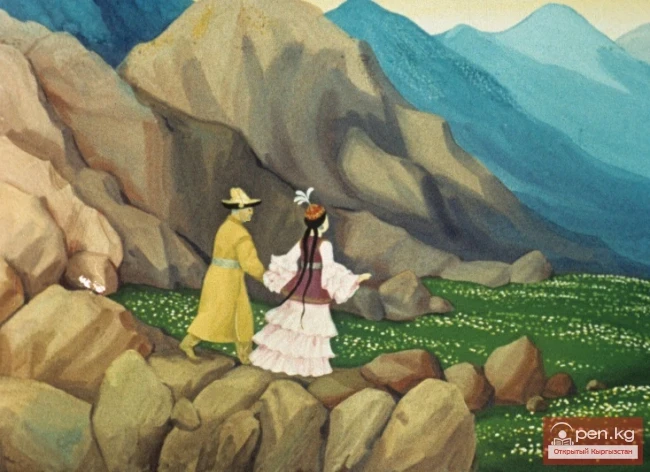

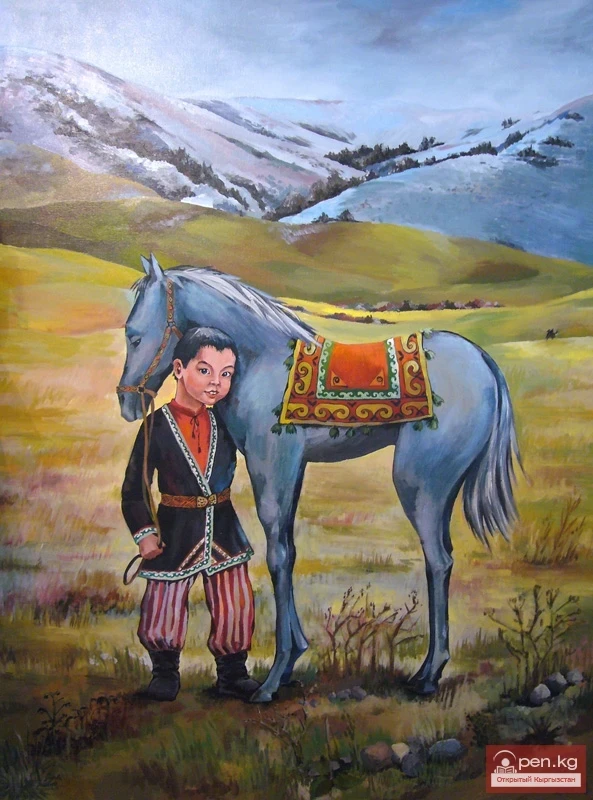

On one of those fine, sunny days, the khan, accompanied by his six closest viziers, went hunting. It was Friday, a day when Muslims work less and pray more to God.

This time, the hunting route passed through a small aiyl called Zhatakchy. Due to the lack of livestock in the summer, they do not migrate to the mountains but remain on the plain, growing wheat, barley, or millet.

It was a hot noon, so all the Zhatakchy people hid in their shabby alachiks—tents—waiting out the scorching heat. Near one alachik, two or three kids were jumping around, and near another, a cow was grazing; that was all the livestock in the aiyl of Zhatakchy. Near the tent where the speckled cow was grazing, a teenage boy was making dung cakes. There was not a single living soul anywhere else...

The khan was surprised to see the boy working in such heat, and he turned his horse to find out how people lived here in the steppe: no trees, no well, just fields of grain around.

— Assalamu alaykum, my dear father! — the khan greeted the boy.

The boy, busy with his task, flinched in surprise and quickly turned around at the sound of the voice:

— Three hundred times I accept.

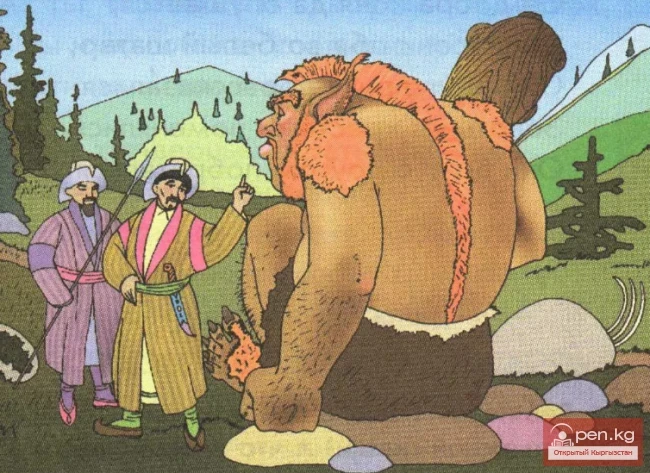

The viziers, hearing the boy's audacious reply, became angry, and one of them raised a whip to strike the boy, but the khan raised his right hand to stop him and signaled for silence.

— Are you not born too early? — asked the khan.

— My parents cried six times before me, — was the boy's reply.

— Are they blind?

— It happened, not by their will.

— Are you not afraid of the heat's revenge?

— It is already pursuing me. What can I do if I am only one third?

— Then change it to three ninths! — advised the khan.

— I know that I will also become an old man. But for now, I have two old pines and one young fir tree. Is it time for me to rest?

— Couldn't someone else water your old pines?

— Three have dried up themselves, and three were cut down by enemies.

— Is there not a main canal for irrigation?

— There is, but the channel is far away.

— And where did the hail come from? Did the wind bring it?

— No. The hail only beat the wheat.

— And where was their main falcon?

— A vulture can never be a falcon.

— How old are they now?

— Multiply my age by five.

— Is it written on your forehead how old you are?

— Add us three to the fingers of your hands.

— Does the earth seem to be the foundation of your deeds?

— It has long been crumbling from the slope.

— Why did your flowers close without blooming?

— There are sunny slopes in your lands, and there are northern ones too.

— And why did a cloud of evil mosquitoes attack?

— They wanted to bring the moon to the earth.

— Farewell, son. Do you have any complaints?

— Tears will dry, but the trace remains.

— I bow low.

— Hands on your chest.

— Art knows no bounds; boldly master it.

— A thousand times. There are eyes, but they do not see, — said the boy, wiping the dried cow dung from his hands and washing them with water.

Propping his chin with the whip, the khan was silent for a while, frowning, and then said:

— Perhaps, perhaps, son. If six come to you, ask for a high price. Everything has its time. I owe you! I will pass the debt with my people. — And the khan, spurring his horse, quickly rode away.

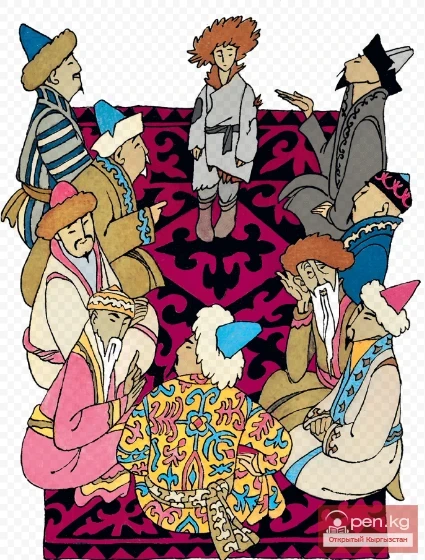

The khan rode in silence for a long time, lost in thought. The six viziers, seeing how suddenly their lord had changed, could not understand what had happened to him. They did not grasp what the khan had talked about with the boy, but they suspected that it was all about that conversation.

For some time, all six rode behind the khan, not daring to approach him: who knows what the lord is thinking? Will he get angry and strike with the whip? Oh, anything can be expected from the khan!

The khan, turning his horse towards the palace, seemed to have forgotten about the hunt. Then the oldest and chief of the viziers, overcoming fear and shyness, caught up with the lord.

— Oh, our lord, if it is not a secret, tell us what you talked about with the boy who was making dung cakes? — asked the vizier.

— Did you not understand anything?

— No, khan, not a single word! — the viziers replied in unison.

— I thought you were the smartest, wisest, and most clairvoyant. If you did not understand a child's babble, then you are the dumbest viziers in the world. Why do I keep you as my chief advisors? Here is my decision: I give you six days. If you do not guess everything I talked about with the boy, say goodbye to life — I will personally chop off your foolish heads!

The viziers dispersed to their homes — of course, no hunt took place. They lost their appetite; even a fatty piece of meat got stuck in their throats at the thought of the khan's threat. They sighed heavily, walked from corner to corner, wringing their hands, tilting their heads to the ceiling — the solution did not come. They secretly invited their best friends, close relatives, old aksakals, and healers. But no one could "translate" the conversation between the khan and the boy.

— So, the khan greeted the boy jokingly, and he replied completely out of place, even rudely, insultingly.

— You speak the truth! If he were a wise, intelligent, clairvoyant boy, why would he be making dung cakes? No, he is most likely the dumbest boy in the world. A fool, that’s all!

— If the boy is a fool, then the khan, who talked to him for so long, is also a fool?

— Be quiet! Do you want to lose your tongue? Our khan is not so foolish as to talk to an abnormal teenager. Something is not right here.

— Most likely, this boy is not an ordinary lad.

— Or maybe he is a shapeshifter, the very Kyzyl-Aley-salam?

The viziers pondered in this manner for a long time, but they could not grasp the essence of the khan's conversation. When all guesses were exhausted, the viziers, driven by the fear of death, saddled the best horses, took food for several days, and rode off in different directions to seek wise men among the people who could decipher the mystery of the conversation. They knew that among the people there were healers, orators, wise men, and magicians: "Perhaps someone among them will help," the viziers hoped.

For four days, the viziers rode through the ails and encampments, telling everyone they met about the khan's conversation, but they did not hear a sensible answer from a single person; and on Friday evening, as agreed, tired and half-hungry, they all gathered at the palace. On Saturday evening, they were to appear before the khan.

Sighing and moaning, pale from fear, sleepless nights, and restless thoughts, they finally decided:

— Let's go to the boy himself. Maybe he will tell us the solution, and everything will somehow work out?

At that time, the boy was boiling water to make tea for his blind parents, slightly diluted with milk, before bedtime. These three unfortunate people — the Zhatakchy — lived on the outskirts of the aiyl.

— Son, do you hear any strange sounds? — the old father pressed his palm to his ear.

— No, father, I hear nothing, — the boy replied, busy with his task.

— I hear the thud of six horses' hooves, and they are good horses, — said the blind mother.

— Yes, yes, those are the tulpars that were here with the khan's horse, — said the old father.

The khan's tulpar is not among them; now I can clearly hear the thud of hooves, — said the son. At that moment, from the western side, over the hills, six of the khan's viziers appeared at full gallop,

Son, they are approaching, hurrying. It feels like they are coming to you or after you, — said the blind father. — In your conversation with them, do not rush, do not get angry, do not be rude. Show what you have learned from us. I hope our teachings have not been in vain. Well, old woman, pay attention with your eyes and ears, I will too. After all, we have seen nothing, we understand everything through hearing and soul.

Blessed be the hour of our son! Go, old man, into the tent. Let the son greet the guests. And the old folks hid in the tent.

The viziers, remembering that the khan greeted the boy first, also wanted to bow to him first, although they secretly despised him, but he, anticipating them, came out to meet them first. They responded to his greeting, dismounted from their horses, and with displeased faces, dragging their whips and leading their horses by the halter, approached the tent and knelt down.

The boy smiled at the strange behavior of the viziers and asked:

— Uncle, did you come for a spark?

The viziers threw a glance at the boy, full of poison and anger, and one of them tried to make a sarcastic remark:

— You guessed it, the khan's fire has gone out, so we came to you for a spark.

— But do not think that all the lights in the khan's city have gone out, — added another. — Stop babbling while you are safe, and better sit with us and tell us what you talked about with the khan then.

— People say: "Evil is an enemy, wisdom is a friend," — said the boy calmly. — I am not afraid of your threats. I will respond to good with good and will decipher the mystery of our conversation. But not for free.

The six viziers were taken aback by the boy's audacious words.

— Do you mean that an ox threatened with death is not afraid of the knife? — one vizier's eyes flashed with malice.

— We can teach you a lesson quickly! — added another. — You will remember your parents. So it is better to open the secret to us quickly; it will be too late later.

— A snake, forgetting that it is crooked, laughs at a frog for being flat, — a furious voice of the father came from the tent. — You want to take our son's life, but who will take your lives? Or are your souls immortal?

At this voice, the viziers flinched: it sounded so deep, as if it came from the underground, as if the old tent itself had spoken. They fell silent and exchanged glances.

— Do not take offense at the words that were said, son, — spoke the bearded vizier. — We have no other choice, so we have come to you. You are not the ox threatened with death, but we are the oxen over whom the knife has already been raised. Speak of your terms.

— Let each of you give me a thousand gold coins, — said the boy calmly and carried a kumgan — an iron teapot with a long spout, filled with boiled water, into the tent. By leaving, he seemed to give the viziers a chance to think about his offer. They argued among themselves a bit and quickly agreed to give a thousand gold coins each.

Of course, they did not have that much money with them, and they sent the youngest to fetch the gold from the palace.

While the boy was having dinner with his parents, the youngest returned with the money.

— Here are your six thousand gold coins, and now quickly reveal your secret, — said the bearded vizier impatiently when the boy appeared at the entrance again.

— What, viziers, son? — asked the father's voice.

— They are petty, father, — replied the boy.

— What, did they not even find a thousand each? — the father's voice asked again.

— Then why did they come? — added the mother's voice.

The viziers exchanged glances and whispered: "I doubt they are normal people," — said one. "I also," — supported another.

— Do not think that I took too much from you, uncles, — said the boy, addressing the viziers. — I asked for the proper payment. So do not be upset. Now I will fully translate our conversation with the khan for you.

Yes, we spoke metaphorically, which is why you did not understand anything. Our conversation concerned many aspects of life, including you. How you did not guess, I do not understand. So listen to what the khan asked me and what I answered him.

Do you remember how the khan first greeted me? He said: "Assalamu alaykum, my dear father." What kind of father am I to him? He called me father because he found me working in the heat. Labor, work — is the father of everything, that is what your khan meant. Everything on earth is created through labor. "I am the khan, I go hunting, to engage in idleness. You are just a simple boy, and you make dung cakes, you engage in work. Therefore, you are greater than I, and I greet you," — that was the meaning the khan put into his greeting.

I replied to him: "Three hundred times I accept," which meant:

"You are the khan, a great man. Thank you for paying attention to me. Who am I compared to you? An ant and a bug? Therefore, I bow to you three hundred times and wish you three hundred blessings in this world."

He replied: "Are you not born too early?" That is, do I not have older brothers? I answered: "My parents cried six times before me," which meant: "Before me, my parents had six boys, but they all died of hunger."

"Are they blind?" — asked the khan. I said: "It happened, not by their will." This should be understood as: "Once enemies attacked us. They took everything, and in addition, deprived my parents of their sight."

"Are you not afraid of the heat's revenge?" — asked the khan. In fact, he was asking: "It is such heat. All the Zhatakchy people have hidden in the shade of the tents, and you are the only one working. Are you not afraid of getting a sunstroke? After all, your head is not even covered."

"It is already pursuing me," — I said. — "What can I do if I am only one third?" I wanted to say that illnesses are already approaching me, but what can I do when I have to feed three, and I still cannot work like an adult. And if I also rest at noon, we will all die of hunger.

"Then change it to three ninths!" — advised the khan. This meant: "Find yourself a job where you can work for three months in sweat, and rest for nine at your leisure."

"I know that I will become an old man too. But for now, I have two old pines and one young fir tree. Is it time for me to rest?" This meant: "I will rest when I grow old. Now, when I have two dependents, working three months and resting for nine, I cannot feed them and myself."

The khan asked: "Could not someone else water your old pines?" That is, do they not have brothers and sisters to whom they could turn for help?

"Three have dried up themselves, and three were cut down by enemies," — I replied. That is, my father had six brothers. Three died of natural causes, and three were killed by enemies.

"Is there not a main canal for irrigation?" — said the khan, which meant: are there other relatives, close ones?

I said: "There is, but the channel is far away," which meant: "There are relatives, but they live very far from here."

"And where did the hail come from? Did the wind bring it?" — asked the khan. This should be understood: "Why did the father leave his tribe? Or did he commit an offense?"

"No. The hail only beat the wheat," — I said. That is, no, my father is a good man; he was expelled by internal enemies...

"And where was their main falcon?" This meant: did your people not have a just khan? Why did the father not turn to him for help?

"A vulture can never be a falcon," — I said. This should be understood as: "They had a khan, but he was dishonest, thinking more about his belly, his entertainment, and not about justice."

"How old are they now?" — asked the khan; he was interested in how old my parents were.

"Multiply my age by five," — I said. "Is it written on your forehead how old you are?" — asked the khan.

"Add us three to the fingers of your hands," — I said.

"Does the earth seem to be the foundation of your deeds?" — said the khan, which meant: "Apparently, your parents are wise people."

"It has long been crumbling from the slope," — I said, that is, they are already so old that they cannot work.

"Why did your flowers close without blooming?" — the khan inquired. He was asking: "If your parents are wise people, why have they not turned to me for help since they settled in my khanate?"

To this question, I replied: "There are sunny slopes in your lands, and there are northern ones too." This should be understood as: "They wanted to turn to you for help, but there are also different people among you. The bad ones deprived my parents of their sight. And how could they appear before your bright eyes if they themselves saw nothing anymore?"

"And why did a cloud of evil mosquitoes attack?" — asked the khan. This meant: "Why did evil people only attack your parents?"

"They wanted to bring the moon to the earth," — I said. This meant: "Mom was a very beautiful woman. She attracted the attention of some rich man. He wanted to take her as his wife. The father, gathering friends from new acquaintances, opposed the rich man. There was a big fight. Three of the father's brothers died in it. But many enemies also fell. The father and mother were captured, and they were deprived of their sight. The rest you already know."

"I bow low," — said the khan. This meant: "You are still very young, but you reason like an adult. You were not afraid to talk to the khan. Well done! Seek your rightful place in life."

I replied: "Hands on your chest," that is, thank you for the interesting conversation, a low bow to your highness.

Then, if you remember, I wiped the dried dung from my hands and washed them. This meant: "Oh, great khan! You are surrounded by many bad people. If you rid yourself of them, as I rid myself of dirt by washing my hands, your future life will be clean and just."

"I owe you," — said the khan as he left. — "I will pass the debt with my people." Do you remember, viziers, such a thing?

— We remember, we remember! — the viziers shouted.

— Well, if you remember, let’s have what the khan passed on.

The viziers exchanged glances.

— He did not pass anything to us! — said the bearded one.

— Yes, yes, nothing, — the others supported him.

— So, your khan is a deceiver? — asked the boy.

— No, he is an honest man!

— Well, then why did he not keep his word?

— We cannot know that.

— Good. Let’s assume he did not pass any item, money, or jewels with you. Perhaps he passed something to me in words? Think carefully. What happened next when you all left me?

The viziers thought for a long time. Finally, the senior vizier remembered:

— When we rode quite far from the aiyl Zhatakchy, we encountered some white-bearded old man in white clothing on a white donkey.

— Did he talk to the khan? What did he ask, what did the khan answer?

— They were silent.

— How? Did they not talk at all? Not even greet each other?

— The khan, pulling the reins of his horse, stood across the road, raising his right hand with the whip to his chest. The old man also pressed his hand to his chest. The khan nodded his head, the old man stroked his beard, then, waving his hand towards the mountains, cried and rode away on his way.

— Understood, understood, — said the boy and fell silent.

The viziers exchanged glances — the boy clearly knew something.

— Do you know what the khan was asking the old man with gestures? — asked the chief vizier.

— I know, — replied the boy. — But you should ask the khan yourself. If he respects you, he will tell everything himself.

— Good. We are leaving.

The boy helped the viziers mount their horses. And they, without saying another word, galloped away. The boy also did not utter a word in their wake.

— Did they not even say goodbye to you? — asked the father when the son entered the tent.

— They did not say goodbye, father, — said the boy.

— The fear of the khan held them back. Otherwise, they would have killed all three of us and taken all their gold. Apparently, these viziers are very bad and evil people, — said the mother.

On the mother’s advice, the son ran to the neighbors and bought a lamb. They slaughtered the lamb in the evening and invited all the neighbors to taste a piece of meat. The Zhatakchy, who were barely surviving on porridge and water, were so pleased with the treat as if they had been at a feast with the khan himself. After eating meat and drinking broth, they thanked the blind old folks, wished them long life, and great happiness for their son, and then dispersed late at night to their shabby tents.

The next day, the boy took his parents by the hand and went with them to the market — it was Sunday. Although the old folks could not see anything, they remembered the colors of the fabrics, the styles of clothing, shoes, and household items well. They told him what and how much to buy, and the son fulfilled their orders. Thus, they bought everything necessary and returned home.

The son prepared a delicious pilaf with fatty lamb. They sat down to dinner outside, in front of the tent, on a new mat. For some reason, the son was pensive and ate the pilaf in silence.

— Son, I do not hear your voice, — said the mother. — What are you thinking about?

— Well, mom, — replied the boy, — I cannot figure out what kind of old man the khan met? What did he talk to him about with gestures? What did he hint at?

— So you are still young, — said the father. — You do not understand some things yet. Then listen to what I will tell you.

— Yes, yes, son, listen to your father, — added the mother. — He is already so old that he will not have time to teach you much. So remember every word of his, and you will draw your own conclusions. Perhaps this is his last instruction.

— The khan, seeing the old man on the path, turned his horse across the path and pressed his right hand with the whip to his chest. Is that right? This should be understood: "Hello, my chief master! What brings you here, in the wilderness, far from the city, where there are no decent roads, and only a rarely visited path flows, which can be blocked by the body of one horse?"

The old man did the same: he raised his hand with the whip to his chest, bowed low, touched his beard, then nodded his head towards the mountains... This meant: "I also greet you, my khan. But behind those mountains hides an enemy; there are as many enemies as there are hairs in my beard. Gather all your troops, prepare for battle. Otherwise, it will be too late."

But the khan misunderstood the old man in a twisted way. He thought the old man was talking about some ransom. Then the old man cried and, lowering his head, rode away on his donkey. His tears meant that the enemies were planning to turn the water back, leaving the khan's people without drinking water and the land without irrigation.

— So that’s what it is! — exclaimed the son. — I also interpreted the old man's gestures the same way the khan did. Now I know what meaning was hidden in them. The khan did not understand the words of the seer! Are we threatened by the enemy? What should we do, father?

— Go, son, without delay to the khan, tell him that the enemy is at the door. If he asks for your advice, then advise the following... — And he whispered something in his ear. — Understood? Do not say a word about our conversation to anyone. If the enemy comes with an army, they may have spies everywhere. God forbid, if they find out that we have uncovered their plans. Then they will undertake a new maneuver, of which we will know nothing.

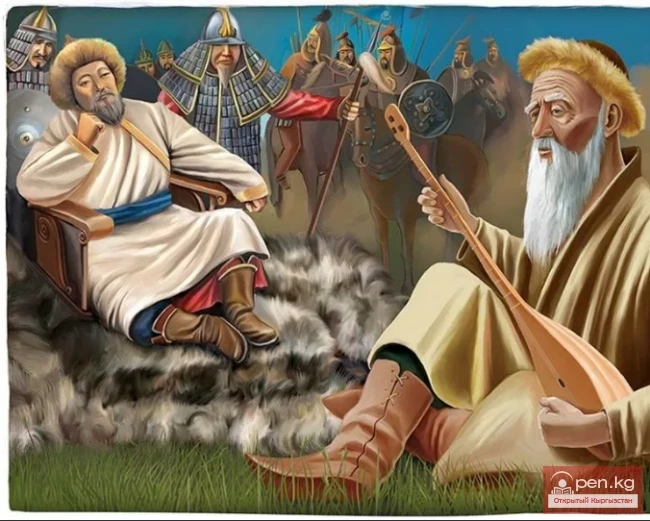

... The khan, seeing the guest in his chambers, immediately recognized him. He greeted the boy like an old acquaintance, with a smile on his lips. But upon learning what news he had brought, he fell into deep thought; the smile vanished from his face like a butterfly flying away from a flower.

"Have I aged so much that I no longer understand the simple signs of the old master? — thought the khan. — Or perhaps I am intoxicated by my boundless power? The enemy has secretly approached my mountains, and I know nothing about him. Urgent measures must be taken!"

The khan summoned all the viziers, advisors, and wise men, told them that the enemy was at the door, that he intended to turn the mountain river in the opposite direction. The courtiers listened to him attentively, with their heads bowed low. But none of them found anything to say. In their speeches, only "ahhs" and "ohhs" could be heard.

— Well, go, — said the khan. — You are all fools, just like me! And it will serve us right if the enemy floods us, takes our livestock and our wives.

All those invited to the council dispersed to their homes. Only the six viziers remained, the same ones who had pleased the khan with the solution to his conversation with the boy. The khan was silent for a while. The viziers were silent too.

— And what do you say, son? — finally asked the khan of the boy. — You see, we are all confused and do not know what to do. Perhaps you can suggest something useful?

— The enemy has come very strong, my lord, — said the boy. — We cannot take him by force. Before coming here, I visited the mountains, where the old master lives. He led me through secret paths to the location of the enemy troops, showed me how many there are, what the warriors are doing, where the sentry posts are set up. At the exit from the gorge, there are a hundred armed horsemen. Behind the mountain, our river flows through a sandy bed. The enemy warriors easily dig that sand, preparing a new bed for the river, thereby depriving us of water. You know that without water we cannot live long. Your enemy is Kara-khan; you have probably heard of him. The great master did not come here; he seems to be offended by you. But he is ready to help you at any time.

— Then, son, go to the Great Master, let him suggest how we should proceed. Take the fastest horse from my stable, gallop without delay.

While the boy was riding to the old man, the khan gathered the people for a meeting, announced preparations for war against the enemy, and ordered to select five hundred of the most resilient, daring, and strong jigits, who could shoot arrows accurately while riding at full gallop. These horsemen, under the cover of darkness, hastily set off towards the mountains, where Kara-khan was now hiding with his army, where they met the Great Master and the boy. The warriors were instructed to destroy the hundred horsemen at the exit from the gorge at the appointed time, and the common people, whom the khan had gathered, all men aged eighteen to sixty, and all women aged twenty to forty, were to stealthily ascend the mountains and prepare to drop stones.

When the enemy warriors, busy digging the earth, went to rest, lit fires, and began to prepare dinner, when they did not expect an attack from anywhere, the khan gave the order to advance. Five hundred of his horsemen quickly removed the guard, and his people unleashed a real landslide on the enemy.

Anyone who has been in the mountains and has seen what it is knows that it is a terrifying sight. One boulder, moved from the top of the mountain, causes a whole avalanche of stones to tumble down the slope.

What began to happen! An avalanche of stones literally crashed down on the enemy warriors who had settled down to rest. Their horses neighed loudly, breaking their reins and hobbles, running in all directions. The warriors were scrambling, trying to find shelter and found none. In just two or three hours, it was all over. Only moans, wails, and cries for help could be heard.

Soon, an anxious night fell over the mountains... They had to wait until morning. The five hundred horsemen hid in a nearby gorge and were ready just in case the enemy had any strength left or reinforcements.

Finally, dawn broke, and a terrible picture appeared before their eyes. Where the enemy warriors had settled for the night, now a mountain of stones rose. Many of the enemy warriors remained buried under the stones and rubble, and those who were lucky enough to survive were mutilated: some had broken arms, legs, shattered spines, and pierced heads. Kara-khan was found in a cave with the viziers, but even he had a cut cheek, a large purple bump on his forehead, and his tongue was bitten so badly that he could not speak. Many warriors were taken prisoner.

— What shall we do with the prisoners and the wounded? — the khan asked the Great Master for advice — he knew that the victory was achieved thanks to the wise old man.

The Great Master, still remaining sad, without looking at the khan, said in a deep voice:

— You managed to defeat the enemy, but you do not know what to do with the prisoners? Well, well!

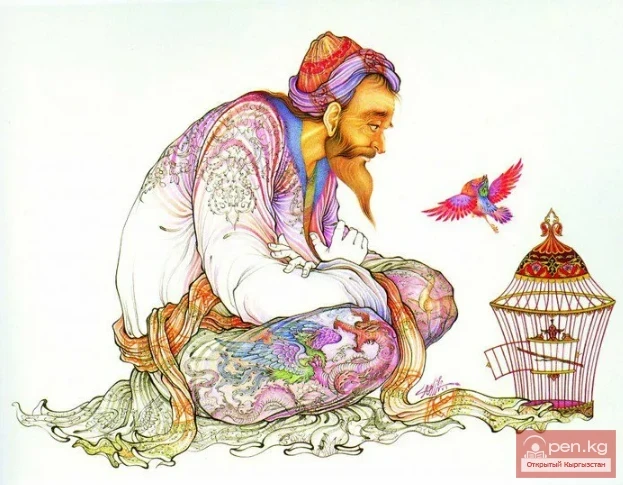

The old man glanced at the boy, gathered a handful of stones from the ground, the size of a small joint bone of a lamb, and, without saying another word, mounted his horse and rode away.

The khan again understood nothing and looked at the boy.

— He said: leave the enemy khan with the viziers in captivity, and let the others, without weapons and horses, go home.

The khan did just that. Then he ordered a great and joyful celebration to be declared for forty days in honor of the victory.