SECRET MISSION

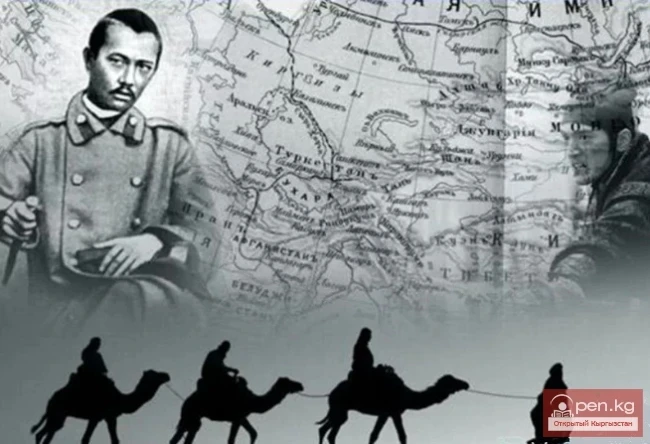

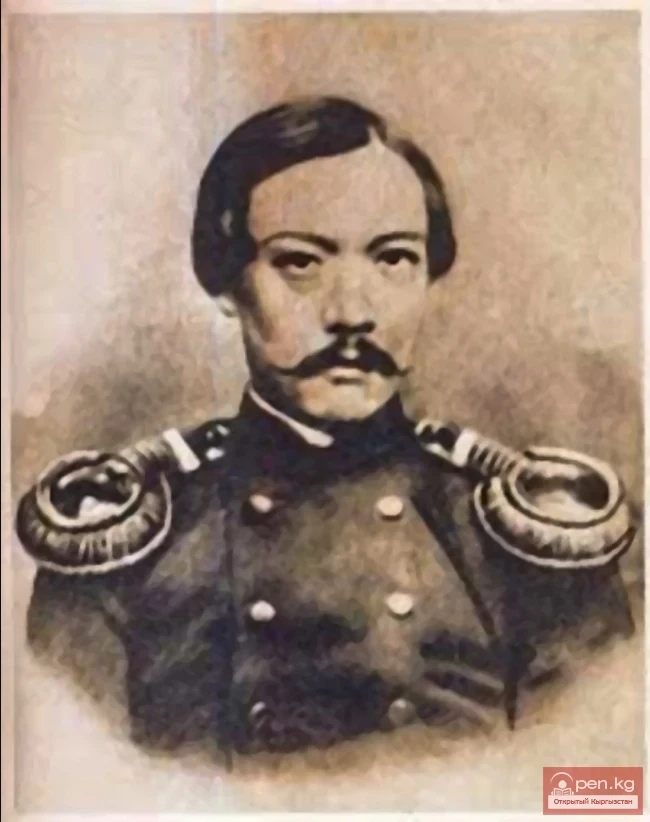

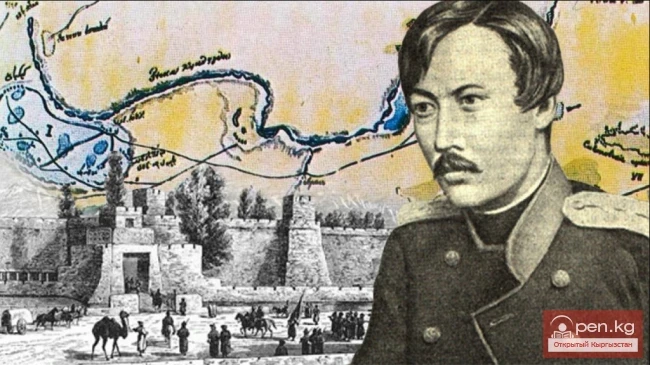

Governor-General Gasfort agreed to secretly send his adjutant Chokan Valikhanov to Kashgar — information about neighboring territories was of interest not only to Siberian military authorities but also to Petersburg.

However, the most difficult task remained — to ensure the success of this complex venture, fraught with many troubles. And here, the wealthy Semipalatinsk merchant Bukash Aupayev came to the rescue. Intelligent and well-acquainted with the customs and traditions of the Central Asian peoples, having traveled to many regions himself, he proposed a plan that was accepted by both Gasfort and Valikhanov. Bukash Aupayev recalled that about twenty years ago, a boy named Alimbai was taken out of Kashgar. According to information cautiously gathered by Aupayev, this Kashgarian, along with his parents, never returned home, and the relatives who remained in Kashgar knew nothing of his fate. Bukash Aupayev suggested that Valikhanov take on the name Alimbai. Additionally, he appointed his trusted man, Musabay, as the leader of the caravan, caravan-bashi, who had been to Kashgar several times and had acquaintances there who could always confirm that Musabay was an honest merchant who had sold quite a few goods in Kashgar in previous years. For reliability, Valikhanov claimed to be a relative of Musabay. Several merchants involved in the conspiracy also provided reliable assistants and servants.

Valikhanov had to shave his head and replace his dapper officer's uniform with a Tatar robe.

On June 28, 1858, Chokan Valikhanov joined the caravan in the Karimula area, located near the city of Kapal.

The caravan consisted of seven assistants and thirty-four servants, all of whom were subordinate to the caravan-bashi.

The main danger lay in the number of people Valikhanov had to initiate into his plans, informing them of his new "origin" and familial ties with the caravan-bashi; they all swore to keep the secret sacred, but there were too many of them for it to last long...

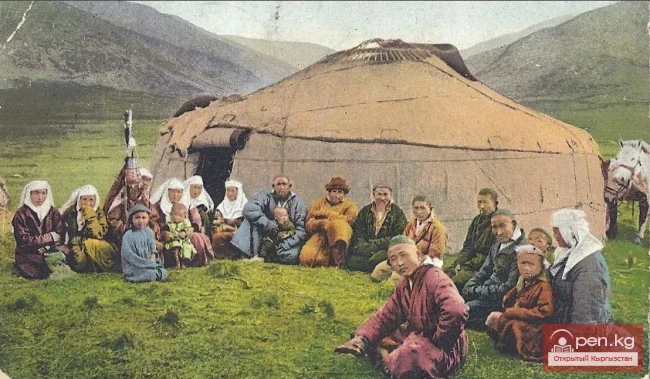

As a relative of the caravan-bashi, Valikhanov-Alimbai was given control of a portion of the caravan — his share — and a portable yurt.

On July 1, the caravan set off and slowly moved along the picket road towards the towering mountains of the Dzhungar Alatau to the south.

Through the Zhak-Altyshmel pass, the caravan crossed the mountains and descended into the desolate, stony valley of the Ili River, which carries its waters to Lake Balkhash... As soon as the eyes adjusted to the harsh desert landscape, a dark strip of tugai — dense riverside vegetation — appeared ahead. The path led directly to a crossing maintained by several enterprising Kazakhs. The camp was set up on a low sandy bank overgrown with reeds, bulrushes, and chiyem. In the evening, clouds of mosquitoes rose from the surrounding marshes and backwaters. There were so many that the hot tea in the bowls was instantly covered with a gray layer of the bodies of the annoying insects, steamed to death, and a constant ringing filled the ears, while the inflamed skin burned from the bites. Valikhanov futilely wrapped his head in rags — he only managed to fall asleep at dawn.

In the morning, a long, complicated crossing began. In a flat-bottomed, poorly caulked boat, they loaded the cargo, and with combined efforts pushed it into the water, while horses tied to the boat by their tails swam alongside, dragging the little vessel to the opposite bank. Of the boatmen, only one sat at the helm, while the others were engaged in the more responsible task of bailing out the quickly accumulating water that seeped through the cracks... The crossing lasted three days, and it was no wonder: there were over a hundred camels in the caravan, sixty-five horses, six yurts, and goods worth 18,545 rubles in silver.

Seven days later, the caravan arrived at the Kegen River, flowing down from the Ketmen Ridge, into the auls of the Adban Kyrgyz...

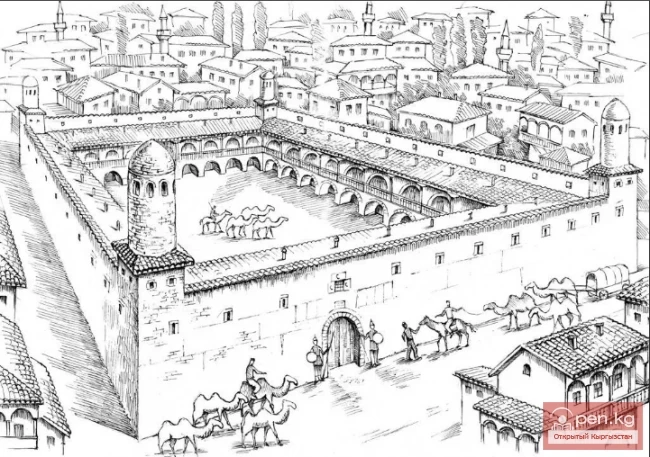

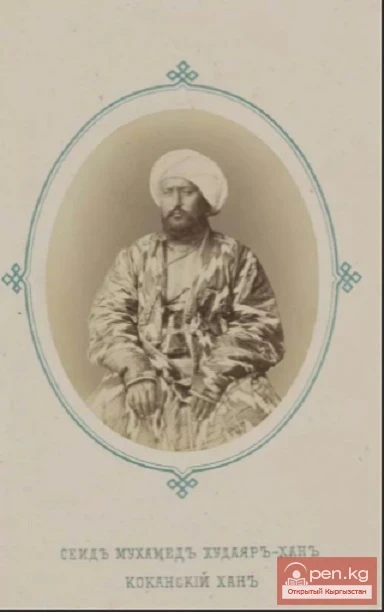

The Chinese authorities allowed all Central Asian peoples to trade with the cities of Altyshar, but the Kokandis enjoyed the privilege — they even had the right to collect duties from all caravans, and in Kashgar, there was a special official appointed by the Kokand khan — an aksakal, who had the rights of a consul and political resident. However, trading caravans were only allowed to pass into Altyshar from the Fergana Valley, through the Kashgar Gorge. The Tien Shan trails were opened by the Chinese only for the passage of livestock, which the inhabitants of Little Bukhara desperately needed; bandits known as barantachi roamed and robbed merchants along the caravan trails of the Tien Shan. Therefore, the Kashgaris proposed to unite, and Musabay readily agreed to this...

Just before their departure, rumors spread among the local population that a Russian officer was hiding in the Semipalatinsk caravan heading to Kashgar. The Kashgaris heard about this too. But neither Musabay nor Valikhanov intended to retreat.

At the last moment, the Kashgar merchants intervened in a fight with Kokand soldiers who were trying to extort a bribe from them, and many of them were delayed until the final resolution.

Thus, strictly following Bukash Aupayev's plan, Musabay's caravan, splitting into separate portions, engaged in barter trade: they bought sheep for Russian goods brought from Semipalatinsk.

Valikhanov was immediately unlucky: by chance, his portion moved to the aul of a familiar Kyrgyz who could recognize the Russian officer in Alimbai and ruin the entire enterprise. Valikhanov had to lie in the yurt for twelve days, citing a severe illness, afraid to show himself to anyone. Fortunately, everything turned out well, and Valikhanov, unrecognized, moved to another aul.

The trade continued for about a month, and the caravan acquired more than three thousand sheep. It was time to move on — winter was approaching, and the high mountain passes could close.

Suddenly, Musabay and Valikhanov encountered the Kashgaris — their caravan was also buying livestock from the Kyrgyz. They had to reveal themselves and say that their caravan was heading to Kashgar. The Kashgaris were not only not surprised but even pleased: according to rumors, the investigation of the matter, Musabay did not wait for them, and although the caravan increased slightly due to the Kashgaris to sixty people, or, as it was counted then, to ten "fires" (there were ten yurts instead of six), they set out on their way.

The meeting with the Kashgaris unsettled Valikhanov and Musabay not only because the rumor about the Russian agent had reached them. From the Kashgaris, they received "the latest," a year-old information about the situation in Kashgar, at that time captured by the hodja Valikhan. Whether the Chinese had driven the hodja away or not — the Kashgar merchants did not know. Both Valikhanov and Musabay understood that going to a city engulfed in rebellion was an extremely risky endeavor. The Kashgaris expressed their attitude towards the rulers of their native city with restraint — they were afraid to say too much, remembering how easily heads could roll in their homeland. But Valikhanov and Musabay had heard enough about the fierce despotism and boundless caprice of the Eastern rulers...

From the Kegen Valley, the caravan began to ascend to the low pass of San-Tash, leading to the Issyk-Kul Basin. The path went among low mounds overgrown with lush, dense grasses — timothy, fescue, hedgehog grass, and reed tangled here with the flexible, creeping branches of galium, wormwood, veronica, and manna grass.

Over the hills and mounds, small steppe eagles soared. Cautious bustards, noticing the caravan from afar, hurried to hide. Occasionally, with the keen eye of a hunter, Valikhanov spotted flickering, like a flash of flame, fiery foxes and involuntarily rose in his stirrups, recalling the hunts in his native steppes with a golden eagle on his leather glove... Here and there on the mounds, old, now collapsed and overgrown with grass watchtowers — circular ramparts — were visible.

At the San-Tash pass, which translates to "counted stones," Musabay showed Valikhanov two mounds — a large one and a small one. They stood side by side, both made of rounded stones smoothed by mountain rivers.

— Brought from afar, — Musabay said mysteriously. — You see, there are no such stones here...

In the evening, by the campfire, Valikhanov heard from Musabay an ancient legend... Many centuries ago, when the mountains were higher and the rivers fuller, almost the whole world submitted to the formidable invincible conqueror — Timur-Leng, overshadowing the glory of all other great commanders. Large and small peoples were submissive to him. But the more power the ruler had, the more despotic he became, demanding ever more proof of his might.

Rumors reached Timur-Leng that the peoples beyond the Heavenly Mountains did not fear him and lived freely, and a huge army led by Timur-Leng himself set out on a campaign against the rebellious... A strange thought came to Timur-Leng: he ordered each warrior to take a stone from the riverbed and carry it with him to the pass. There, at the pass, the warriors piled these stones into a tall mound. Galloping on a battle, under chain mail, Akhal-Teke stallion brought from Turkmenistan (so far did the conqueror's domains extend!), Timur-Leng proudly thought that he had erected yet another monument to his might. Someday, descendants would count the stones and reverently bow before the memory of the ruler who gathered thousands of thousands of warriors under his banners...

Timur-Leng spent many years on campaigns and conquered many new peoples with fire and sword. Returning, he again came to the pass, already well known as San-Tash. And here a new thought struck the ruler, and he ordered that each warrior take a stone from the large mound and place it beside it... The old mound did not decrease in height, but nearby a second, smaller mound arose, tens of times smaller than the first. Thus, Timur-Leng learned how many warriors perished conquering foreign lands for him, and how many returned home. Timur-Leng was satisfied: the more soldiers died in battles, the greater the glory of the conqueror, the more songs the steppe akyns would compose about him, the longer he would be remembered in cities and among nomads...

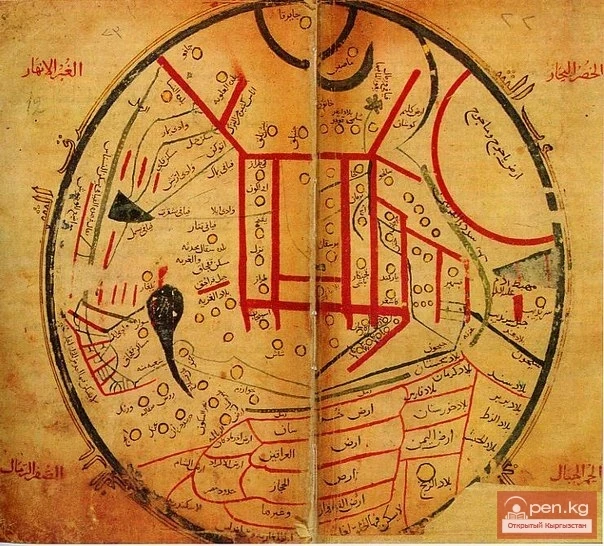

Whether Timur-Leng or another conqueror passed through the Issyk-Kul Basin and the San-Tash pass, Valikhanov could not decide, listening to Musabay's leisurely tale. He stared into the darkness without blinking, and before his mental eye, fantastic visions of the past flashed by... Conqueror replaced conqueror, throngs of slaves were driven along mountain and steppe roads, the ruins of cities smoldered, and gray dust slowly buried the corpses of men, old men, women, and children... So it was. But these lands were not only famous for conquerors. Once, a magnificent culture, whose memory will endure through the ages, flourished under the clear blue Central Asian sky. Here lived and created the immortal works of the great physician and sage Ibn Sina, the unparalleled poet and humane vizier Navoi, here the Bukhara emirs observed the movements of celestial bodies and compiled astronomical tables...

A complex, tangled history, in which the most exalted wisdom is intertwined with baseness, with the gravest vices, the history of peoples who created beautiful cities, and the history of despots who destroyed them at their whim... But what did Valikhanov know about this history?..

Almost nothing... Vague, fragmentary, sometimes contradictory information — that was all he had... And deep down, Valikhanov was angry with himself; he wanted to feel with his own hands, to see with his own eyes every inch of the long-suffering land, to tell the whole world about its glorious and tragic history... And he swore to himself that he would do it...

— What are you thinking about, Alimbai? — asked the caravan-bashi.

Valikhanov flinched and shivered slightly.

— Just, — he replied, shivering. — I was listening to you. But it’s time to sleep.

— Go, sleep. And may you dream of the cheerful city of Kashgar, — Musabay clicked his tongue and squinted slyly. — Oh, what a city Kashgar is! There is no life like it anywhere else...

But Valikhanov remembered the hodja, and Musabay's words did not reach his consciousness.

The next day, the caravan descended into the Issyk-Kul Basin along the valley of the Jargalan River. On the northern shore of Issyk-Kul, by the Kara-Batpak River, a Cossack detachment awaited Musabay and Valikhanov, assigned for protection. However, fearing that the presence of armed Russians might raise suspicion, Valikhanov sent a messenger to the commander of the detachment asking him not to approach the caravan and to follow it at a distance under the guise of reconnaissance of the area.

Valikhanov did not wait for the caravan to reach the shore of Issyk-Kul. Spurring his horse, he galloped ahead and, leaving the road, rode straight to the lake. His path was blocked by the smoky-gray wall of "jirgana" — thorny sea buckthorn, almost surrounding the entire lake in a solid belt. Only here and there among the sea buckthorn were green branches of barberry, with clusters of bluish berries, and the feathery stems of reeds rose high... Valikhanov dismounted and, avoiding the shallow marshes — sazy, sinking into the loose white sand, cautiously made his way through the thickets. The boundless azure expanse of the lake opened before him. Valikhanov looked and did not know what to compare the unique colors of Issyk-Kul to. With the heavenly blue?.. No. Heavenly blue is simpler, coarser, weightier... The delicate blue waters of Issyk-Kul shimmered, flowed, ignited with sparks, and seemed to be illuminated from within, from the dark depths, by silver rays of mysterious lamps; the lake lived, trembled, momentarily frowned, and then brightened again, like a sensitive, responsive organism. A light breeze brought small waves to the gently sloping sandy shore, and they, tumbling onto the sand, flared up in blue flames at the break... And in the distance, on the opposite shore of Issyk-Kul, the peaks of Kunghei-Alatau were faintly visible, hovering above the earth like dark clouds.

Valikhanov crouched down, scooped up water with his hand, and touched it with his lips: the water was slightly salty, unpleasant to taste... Issyk-Kul, the "warm lake," does not freeze even in the harshest frosts, and in autumn, when winds sweep down from the snow-capped peaks, storms arise on Issyk-Kul, which must be just like those at sea, which Chokan Valikhanov had never seen...

He slowly made his way back. Suddenly, with a loud caw, a male pheasant sprang from under his feet and disappeared, flashing a purple feather in the sun. Valikhanov flinched, laughed, and, jumping on his horse, raced after the caravan.

On September 9, after spending the night on the bank of the Kyzylsu River, at the foot of the Terkei-Alatau ridge, the caravan entered the Zaukin Gorge, leading to the pass, while the Cossack detachment turned back. The last thread connecting Valikhanov with his homeland was severed, and now he could no longer hope for anyone's protection.

The Terkei-Alatau mountains, which border the basin from the south, rise two to three thousand meters above the level of Issyk-Kul, forming a massive jagged wall, with gorges cut into this wall in a few places, which Valikhanov was in no hurry to follow his companions — as if he could not part with the blessed Issyk-Kul Basin, with its rare auls and small fields... Writing in his diary about yesterday's observations, he sat by the river, along which poplars grew; the wind tossed the leaves, and the windward edges sparkled in the sun like fish scales. On both sides of the river, parallel to the mountains, stretched flat steppe spaces overgrown with grasses and wormwood; it was dry in the Issyk-Kul Basin — the mountain ranges attracted clouds, and they shed moisture over their peaks. Leaning against the ridge, the narrow and deeply cut waterless ridges (later they would receive another, Russian name — "shelves") were also overgrown with steppe and semi-desert plants — yellow chilik, prickly cushions of acantholimon, rare sprawling bushes of cherry, bluish brushes of ephedra with sweet red berries on leafless branches, grave grass... And only significantly higher in the mountains, where the caravan had already gone, thickets of wild rose, barberry, rowan, and irga descended to the river, and on the gray-green slopes, the color of overcoat cloth, slender Tien Shan firs appeared, resembling cypress trees from a distance...

The previous evening, Musabay had frighteningly recounted that on the other side of the Terkei-Alatau lay a harsh cold desert — syrt. There, eternal, unmelting snows lie, frost grips the earth all year round, and even in the height of summer, snowstorms occur. But the most terrible thing in the syrts is the suffocating air, which causes the disease tutek, from which both people and animals suffer. To protect oneself from it, one must adhere to a diet and eat as much garlic as possible.

This tale could hardly unsettle Valikhanov — where others have passed, he would pass too; besides, Pyotr Petrovich Semenov had already been to the syrts. But Valikhanov imagined that the syrts were at a great height, where due to the thin air, travelers had a hard time.

At night, a horse disappeared from the caravan. Musabay reasonably suspected that it had been stolen by the Kyrgyz who had joined the caravan along with the bian Janet, and sent servants after the trail. They caught up with the thieves in the forest, by the fire.

In the ensuing scuffle, several thieves were captured, including Janet's brother. Janet, who himself engaged in baranta and had a loud bandit reputation, pretended to be angry with his brother, left him in the caravan, and rode off to the aul, promising to immediately return the horse on which one of the thieves had managed to escape.

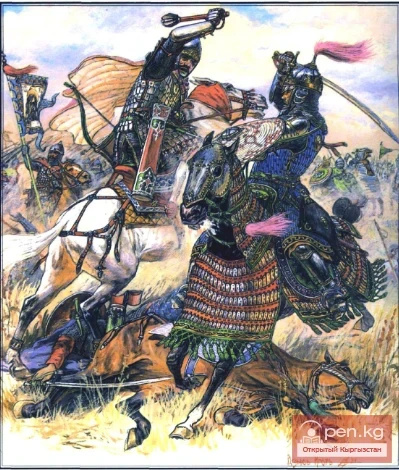

Two days later, an armed gang of Janet, numbering about seventy people, attacked the caravan.

Gunfire forced the barantach to retreat, taking the wounded with them. The first attack was successfully repelled, but everyone understood that this was just the beginning, that new clashes awaited ahead with the greedy barantachi.

Above the forest belt, where Tien Shan firs were replaced by thickets of Turkestan juniper, locally known as archi, the convenient road through the Zaukin Gorge ended, and a steep, difficult ascent began up a slope over a thousand meters high. The white skeletons of animals, washed by the rains, visible below in the bottom of the gorge, foretold difficulties.

Now glaciers, sliding down from the peaks, snowdrifts, and cornices were visible nearby. The caravan spent the night on a still green alpine meadow, but the frosty breath of the glaciers forced them to huddle around the fire, wrapping themselves in fur coats.

The livestock was watered in a small lake — a glacier had been in its place several decades ago, but gradually it had receded, and behind a high transverse mound of moraine, meltwater had accumulated, greenish in color.

In the morning, the sky darkened, and large fluffy snowflakes began to swirl in the gray damp air. The pack horses and camels loaded with cargo slipped on the wet, darkened stones from the melting snow, and some of them fell and died. During the ascent, the caravan lost five camels and two horses...

Having passed the Zaukin pass, Valikhanov, outpacing the caravan, rode ahead and stopped his horse. He entered another, unusual and strange world. Here, the mountain rivers did not roar, and rocky peaks did not rise. A wide, gently rolling plain stretched before him. Here and there, small lakes, already covered with ice along the shores, were visible, quiet rivers, bending between the mounds, flowed slowly eastward. But what struck Valikhanov the most were the mountains: they did not appear majestic, inaccessible, raised to the very sky here. They began right here, and their dome-shaped peaks seemed no higher than the steppe mounds. And the glaciers did not sparkle in the sky, devoid of any grandeur; they crawled, sprawling, onto the plain, and on their murky-white surface, black stripes and speckles of rocky debris were visible.

Several times during the evening, it began to snow, but the night turned out to be clear and frosty. Wrapped in a fox fur coat, Valikhanov stepped out of the yurt. The frozen, motionless world lay before him. The low, perfectly round moon generously illuminated the yellow-tinged black sky. The earth, every stone, every blade of grass was wrapped in thick hoarfrost, and the moonlight shattered, sparkling in the frost crystals with dull little lights. Shadows from the hills, scattered like deep black spots across the silver plain, seemed like bottomless abysses. The silence was so profound that the frozen air could crackle with movement... Only occasionally was it broken by the snorting of horses and the melodic ringing of a bell on the neck of the lead ram; but even this sound, barely starting, cooled and fell to the ground in ice chips... During the night, the inside of the yurt was covered with frost, as in winter in the native Kazakh steppes of Valikhanov...

The caravan set off in the pre-dawn twilight. The frozen ground rang dully under the hooves, but by midday it thawed, and the clay stuck to their feet, making it hard to walk. In the hollows of the lakes, brave diving ducks swam in the icy water, Valikhanov did not feel suffocated by the altitude, and only when he jumped off his horse and walked on foot did he feel his heart pounding heavily and loudly from the unfamiliar exertion, and blood pulsed with a ringing in his temples... The quiet, frozen plain lay at an altitude of about four thousand meters above sea level...

The caravan's path through the syrts was not easy; it was restless around, Musabay discovered the trail of a caravan that had passed through the syrts two days earlier. The caravan was marching at an accelerated pace, not lighting fires at night... The Kashgaris who had joined Musabay and Valikhanov determined from the corpse of a fallen horse that their comrades had passed here, detained by Kokand soldiers.

In Musabay's caravan, the pack animals had become emaciated, their legs damaged, and at each stop, several dead animals were left behind. Dozens of sheep were dying...

Now Valikhanov was riding through places where no scholar had been before him — even Pyotr Petrovich Semenov had not reached here, and he involuntarily remembered his mentor and colleague, about parting with him in Omsk. Semenov had long been living in Petersburg, engaged in important state affairs, and hardly suspected that right now, on this day, at this moment, he, Chokan Valikhanov, was riding through the Tien Shan syrts, continuing his work...

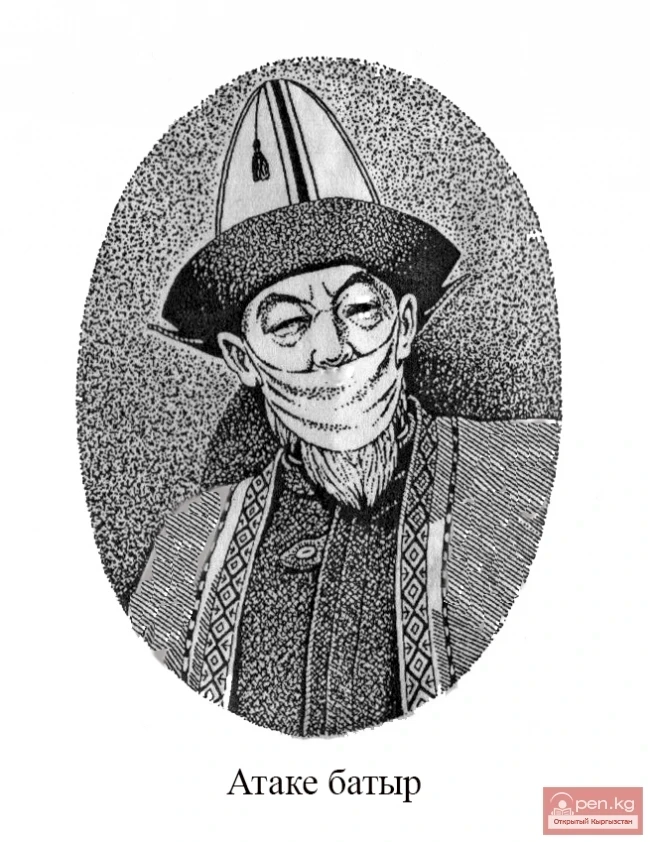

The greatest dangers awaited the caravan at the Terektin Gorge, on the southern edge of the Tien Shan. Only sixty versts separated the gorge from the first Chinese outpost, but near the gorge roamed the scourge of caravans, the barantach Atek, a Kyrgyz from the chon-bagysh tribe. Following the advice of the Kashgaris, Musabay sent messengers to the Kashgar aksakal asking for soldiers to be sent for assistance.

Armed Kyrgyz appeared as soon as the caravan entered the gorge. At first, they circled from a distance, not daring to approach, and then entered into negotiations for a ransom for safe passage. They behaved modestly, did not threaten, and took only eight pieces of red leather from the caravan. Experienced Musabay was astonished, clicked his tongue in surprise, and could not understand why the Kyrgyz were so timid...

In the Terektin Gorge, the caravan caught up with the summer descending into the valleys: the days were blue, warm, the bushes along the river were turning green, and it was hard to believe that just a day ago, in the morning, they had to carefully wipe the curly, hoarfrost-covered backs of the horses with a felt coat.

At the last pass of Kok-Kiya, when the caravan was carelessly ascending to the saddle, loud war cries were heard from behind. A scattered crowd of Kyrgyz horsemen, led by the barantach Atek, overtook the caravan and blocked the narrowest part of the passage, obstructing the caravan's way. These were the same Kyrgyz who had treated the caravan so kindly. Some of them were performing tricks a hundred meters away from the caravan that had taken up defensive positions, shouting threats while waving their straight sabers (sapas) and spears. No one could understand why their attitude had changed so sharply, but Musabay had no way out: the caravan could not pass through the passage occupied by the Kyrgyz, nor could it defeat the numerous gang.

During negotiations, the Kyrgyz demanded an enormous ransom from the caravan and would not make any concessions. It is unknown how the prolonged dispute would have ended if a detachment of Kokand sipahis, sent from Kashgar by the aksakal, had not arrived in time. And although there were only five of them, the caravan drivers, uplifted in spirit, went on the offensive and defeated the barantachis in a short battle.

A Kyrgyz captured explained the reason for the strange behavior of his tribesmen: the caravan of Kashgaris that had passed before them had spread the rumor that behind them, following Musabay's caravan, was a detachment of Russians numbering up to two hundred armed horsemen. That is why Atek had behaved so modestly, and his auls had even moved away from the main road into the gorges — to stay out of trouble. Only after confirming the deception did Atek rush to pursue the caravan.

The leader of the sipahis, toksoba, handed a letter from the aksakal to the caravan-bashi and personally dressed Musabay, Valikhanov, and the other assistants in robes sent as a sign of special favor from the aksakal.

From the toksoba, Valikhanov learned that Kashgar was again under the reliable protection of the Chinese, and the rebellious hodja Valikhan had fled beyond the borders of Altyshar...

On September 27, the caravan crossed the rather conditional border of the Chinese Empire in these regions and approached the first outpost — a small fortress surrounded by a clay wall with four towers at the corners.

They set up camp. That night, Valikhanov could not sleep. Tossing on the felt mat smelling of horse sweat, he tried to imagine what awaited him in this country, and an involuntary anxiety pressed on his chest, driving away sleep. All the difficulties and dangers endured on the way now seemed trivial to him. And the future... If Valikhanov had made snowmen in his childhood, he would have every reason to compare his journey to a rolling snowball; the further he went, the more dangers he encountered on his path... Valikhanov grunted, scratched his narrow chest, and suddenly, as if quite out of place, the thought came that it was long overdue to wash in a bath, even if it was small, heated in the traditional way, with a stove over the heated stones, like in the yard of his landlady in Omsk... This thought amused Valikhanov and distracted him from his gloomy reflections. No, it would not be soon that he would have to scrub his itching, dirty body with a soapy washcloth, change his dirty, heavily sweat-smelling shirt. In the campaign, the pampered, accustomed to a different way of life staff captain of the Russian army should not differ from his companions, who lived by their grandfathers' steppe laws and did not change their lower shirts until they rotted on their bodies...

There was no Chinese officer at the guard post, whose duty it was to count and record the number of people, camels, and horses passing towards Kashgar. They waited a long time for him, but then the Chinese official with a gilded ball on his hat — boshko, after receiving a bribe, allowed the caravan to continue its journey.

Experienced Musabay, however, made an unforgivable mistake at the post, the consequences of which soon became apparent: he did not give a gift to the interpreter, and the offended translator sent false information about them to Kashgar; he called them Tatars (and the Tatars were treated suspiciously in Kashgar), indicated that only fourteen people had come to the post, not fifty-seven, but that in reality, there were more than a hundred of them and they were all armed with rifles.

Unaware of the danger, the caravan calmly made its way to Kashgar, passing low clay ridges, overgrown here and there with prickly yan-tak grass, and finally, from one of them, Valikhanov saw in the distance the bluish-green thickets of gardens surrounding the suburbs of Kashgar...

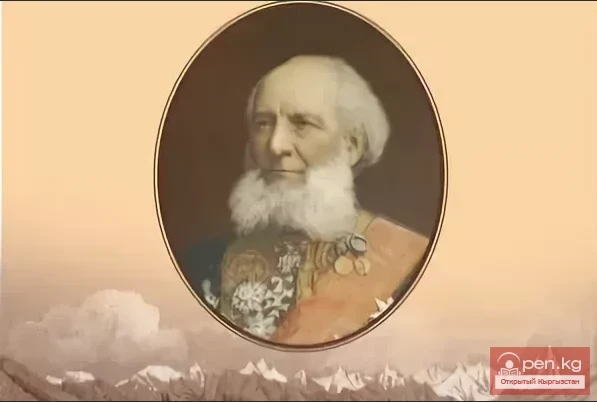

Acquaintance of Chokan Valikhanov with Semenov-Tyan-Shansky. Part 3