AGAIN HODJA VALIKHAN, AGAIN SHLAGINTWEIT

The caravan of Musabay occupied eleven stalls in the "Kunak" shed. The trade was successful, and by the very first week, almost all the goods were sold at a great profit.

According to the calculations of the caravan-bashi, it took at least two months to fatten the pack animals. Valikhanov decided to take advantage of this and make a trip across the country. He wanted to visit the Yarkand oasis and the city of Yarkand. There was still some un sold sheepskin left in the caravan, and Valikhanov, together with the Bukhara man Mukhsin Sagitov, decided to take it to Yarkand. They received exit tickets from the aksakal, and on October 10, leaving his young wife behind, Valikhanov left Kashgar.

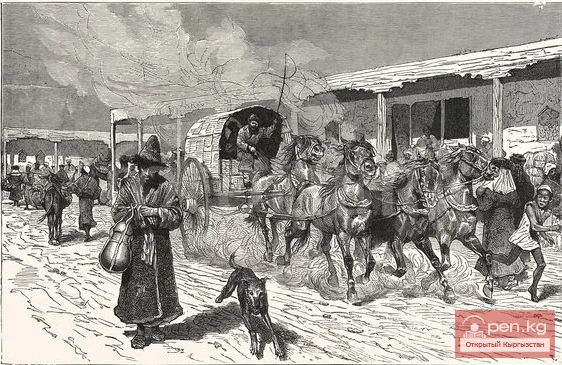

The goods with the contractor were sent ahead in advance, and Valikhanov traveled light. The road to Yangigisar and beyond to the Kokravat Urtenge went through densely populated oases, fed by the waters of mountain rivers, past groves of mulberry, cherry, and peach orchards, fields, and auls. Beyond Kokravat, the oases ended, and the sandy desert of Kum-Shaydan began. Monotonous sandy hills, only occasionally covered with saxaul, stretched from west to east; now and then, there were bitter-salty lakes framed by reeds; sometimes the sandy spaces were replaced by clayey, almost lifeless areas, with protruding whitish salt that looked like snow from afar. Along the road lay half-buried skeletons of fallen camels and horses... Mukhsin-Sagitov told his curious companion that further along, by the great river

Yarkand-Darya, he would encounter coastal forests of dzhengel, stretched in two narrow strips along the

river...

But Valikhanov was not destined to penetrate into Yarkand, nor was he destined to see with his own eyes that the Kum-Shaydan desert was just a small section, separated by the Yarkand-Darya from the vast Takla-Makan desert...

The riders were descending from the sandy ridge when a dull sound of hoofbeats was heard behind them. Someone was catching up with them. Preparing his pistol just in case, Valikhanov waited... However, the alarm turned out to be unfounded: a courier from Kashgar caught up with Valikhanov and handed him a letter in which Musabay reported unpleasant news: in the team, the brother of Khan Khudoyar, Malibek, had raised a rebellion and seized the throne, while Hodja Valikhan had fled in an unknown direction again. Musabay advised him to return to Kashgar immediately.

While Valikhanov was traveling across the country, significant events occurred in Kashgar. Rumors of the uprising in Kokand reached Kashgar in the first half of October, almost immediately after Valikhanov's departure. At that time, messengers arrived at the aksakal Nasyraddin from both Khan Khudoyar and his brother Malibek, demanding the immediate dispatch of zaket. The poor aksakal found himself in an extremely difficult position: if he sent zaket to Khudoyar — what if Malibek wins, if he sends it to Malibek... but it is quite possible that the khan will defeat the rebels. Aksakal Nasyraddin decided to wait, and he was not mistaken: on October 15, reliable news came about Malibek's installation as khan, and Nasyraddin received a khan's decree — he was retained in his previous position and assured of the khan's favor...

But Aksakal Nasyraddin was too experienced a man to believe in the sincerity of the khan — such tactics were often employed by new rulers to prevent the aksakal from hiding the collected money...

The representatives of the new aksakal arrived in Kashgar the next day, immediately placed Nasyraddin under arrest, and completely robbed him. And immediately, the attitude towards the disgraced aksakal and his son changed — former friends ignored them in the narrow streets of Kashgar, where it was already difficult to pass. In this regard, the hospitable Kashgarians were no different from other mortals, and the hot-headed, naive young Valikhanov was sincerely surprised and indignant.

Valikhanov's heart was anxious. Who knows what the arrival of the new aksakal would bring him? And the day, as if on purpose, turned out to be gloomy and cold. The leaves were falling from the poplars, cherries, and mulberries. On the terraces of the mosques, the clergy, the akhuns, along with the students of the madrasah, loudly recited the prayer "Knut," which has a rare ability to disperse clouds, reading for a long time, fervently, for there is nothing more frightening for a clay city than a heavy rain...

Nor-Magomet turned out to be a cheerful and extremely sociable man. He preferred riotous mashrebs to serious matters, and the Semipalatinsk caravan traders easily got along with him. Generous gifts finally convinced the aksakal that his new acquaintances were deeply respectable people, true Muslims, and he invited Musabay and Valikhanov to his home almost every evening. And after the second aksakal stood up for the Semipalatinsk merchants, the Kashgar beks also changed their anger to favor, and the Semipalatinsk traders gained almost fabulous freedom; they were even allowed to walk at night in the streets, which was not recommended for other townspeople, as nighttime walks threatened very unpleasant explanations in the dynza - city police.

In December, the first snow fell, the ponds froze, and the water stopped flowing into the irrigation ditches. To Valikhanov, accustomed to Siberian frosts, the winter did not seem cold — the temperature hovered around zero and only dropped significantly below — to 8-16° frost a couple of times throughout the winter. But the Kashgarians had a different opinion about their winter — especially the street singers, beggars, half-crazed "bengi" addicts, poisoned by hashish and opium — all those who had no means to buy very expensive firewood, who wrapped their bony, unwashed bodies in tattered, worn-out robes or old, discarded Chinese epancha... After such frosty nights, the bodies of the outcasts, unable to find warm shelter, were always taken out of the city, and the songs of the blind sounded particularly sad, telling of the hard life in Kashgar, where it is harder to keep one's head than to feed a horse, about that side of Kashgar life that cheerful legends about the merry city so diligently avoid touching...

However, at lunchtime, the sad songs of the blind successfully drowned out the sounds of the Chinese gongs and drums: according to the rules of city etiquette, the lunch of the hakim-bek should be accompanied by boisterous music, performed on a special tower, specifically built for this purpose in Kashgar...

Valikhanov could not undertake a new trip across the country, but he did not waste time: he searched for ancient handwritten books, decaying in the shops of illiterate merchants; he bought samples of handicrafts, the precious "stone of eternity" jade, so valued by the Chinese — mined in mountain rivers; he collected information on the economy of the region, its history, and especially carefully — about the events of recent years, about Hodja Valikhan.

And gradually, Valikhanov managed to reconstruct the entire history of the rule of the fanatical hodja. He was told about him by the old akhuns, merchants who barely managed to keep their heads, beggars whom Valikhanov fed in his shop, bengi and kumarbazy — gamblers and usually the most zealous participants in any city turmoil...

Hodja Valikhan, the fighter against the infidels, left a terrible memory behind. Trade in the city ceased, industry froze, and the sacredly traditional orders were trampled upon: women were forbidden to go out on the street with their faces uncovered and even to braid their hair, the people, as in Kokand, were forcibly driven into mosques; prisons were filled with both the innocent and the guilty, and the pyramid of human heads on the banks of the Kyzyl-su river grew continuously. Everyone lived in constant "expectation of death" and warned each other: "If it is not hard for you to carry your heads — be silent!" Terrible rumors were passed from mouth to mouth. Yesterday at the mashreb in the palace of hakim-bek, hodja Valikhan ordered the head of a musician who dared to yawn in his presence to be cut off in front of the guests. Today, the best Kashgar gunsmith came to the hodja and brought him as a gift magnificent sabers with blades that shimmered blue. They were so sharp that they could cut a flying feather. But Hodja Valikhan tested their quality differently: he personally cut off the head of the gunsmith's son and rewarded the master with a robe for the good gift...

The Kashgarians cursed the hodja and awaited the Chinese as their saviors...

But Valikhanov had not yet managed to catch up with the German traveler Adolf Shlagintweit...

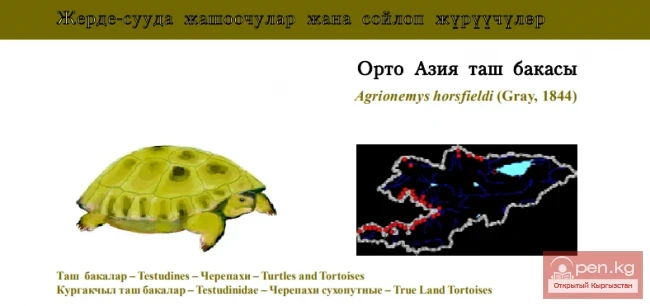

Society in Kashgaria was divided into three classes: beks (administration), akhuns (spiritual figures), and alvonkash (common people). It was not particularly difficult for Valikhanov to familiarize himself with the life of the beks, akhuns, as well as with the merchants who had risen to "people." But it was with great difficulty that he managed to gather information about the life of the frightened and downtrodden common people... And then a sad picture emerged. Heavy taxes eternally condemned artisans and farmers to a semi-poverty existence — they were devised so cunningly that with the slightest increase in wealth, the tax immediately increased as well. Even those who managed to amass a fortune pretended to be beggars, hiding even from their neighbors, or fled from the blessed Altyshar to other countries. Chinese officials, local beks, and even soldiers divided the entire population among themselves, creating an extremely profitable clientelism system for themselves.

The "clients" assigned to officials were obliged to supply their masters with meat, fat, grain, and other food supplies for free if they were townspeople, to plow their land, and to perform household chores in turn if they were villagers... Valikhanov bitterly realized that the slanders of some Kokand or Bukhara people against the inhabitants of Kashgaria were false. No, before him stood not a lazy and depraved, but a hardworking, yet extremely downtrodden people. "If the Kashgarians could enjoy the fruits of their labor," thought Valikhanov, "they would be one of the richest Eastern peoples..." The same high, exorbitantly inflated taxes hindered the development of industry and trade, and in terms of industrial development, Altyshar lagged behind neighboring regions of Central Asia...

One could not help but marvel at the diligence of the farmers who cultivated the meager semi-desert soils with a plow with a wooden share and a board with nails, which served as a harrow. Yet they still harvested large yields of wheat, rice, jugara, barley, corn, hemp, sesame, and tobacco...

Valikhanov managed to obtain the first information about Adolf Shlagintweit, strangely enough, from his own wife, to whom he paid so little attention. She told him that last summer she had seen executioners leading a light-haired and fair-skinned foreigner — a freng — through the streets of the city. The freng's hands were tightly bound behind his back with belts. He walked with long strides, looking straight ahead, and the hems of his robe flared out as he moved. The executioners led the freng out of the city gates, and after that, no one saw him again...

What a strange man the chauken turned out to be — how many people did the hodja execute, and is it really so terrible that he ordered the head of the white-faced freng to be cut off?! But her husband became anxious, left her, and began to pace back and forth in the room.

This is what Valikhanov eventually learned about the fate of Adolf Shlagintweit.

Having infiltrated Kashgar, Shlagintweit decided to introduce himself to Hodja Valikhan and asked a familiar merchant, Naman-bai, a relative of the hodja, to procure him Indian gold brocade and Kashmir shawls as gifts. Shlagintweit told him that he was an Englishman and was on a special mission from Bombay to the Kokand khan. But Naman-bai did not have time to fulfill the traveler's request. The city was already besieged by Chinese troops, and the associates of Hodja Valikhan, believing that the freng was knowledgeable in military affairs and could help defend the city, seized him and took him to the hodja. Valikhan, that day, as usual, indulged in smoking hashish and, almost without talking to Shlagintweit, demanded that he hand over all the documents intended for the Kokand khan. Shlagintweit refused, and this predetermined his fate: Valikhan ordered him to be executed and his head to be thrown on the pyramid... Shlagintweit understood that asking for mercy was useless. And he did not ask for it. With his head held high, accompanied by the astonished gazes of the townspeople, among whom was also the chauken, Shlagintweit walked through the streets of Kashgar for the last time...

Valikhanov experienced his tragedy as his own, and who could guarantee that he himself would safely reach the Russian border?.. Valikhanov remembered too well that almost every volume of the "Notes of the Russian Imperial Geographical Society" published obituaries about the next martyrs of geographical science who perished in Asia, Africa, South America, or the Arctic... Yes, no one better than Valikhanov could imagine the true price of geographical discoveries...

Even if his journey ended successfully, would the price of the information he obtained about Altyshar not be too high?.. After all, in essence, he did not do much — he merely stepped over the threshold that Peter Petrovich Semenov had ascended...

Once again risking, Valikhanov made a desperate attempt to find the precious diaries of Shlagintweit, but unfortunately, it was unsuccessful — Shlagintweit's diaries were irretrievably lost...

The rule of the bloody hodja Valikhan ended soon after the execution of Shlagintweit. Betrayed by almost all his associates and cursed by the population, the hodja fled from Kashgar and, after some adventures that ended quite well for him, settled again in Kokand.

...The horses and camels had long since fattened in the pastures, their wounds had healed, and it was time to prepare for the return journey. But winter raged both on the plain and in the mountains, and the mountain passes were closed. The only accessible route was through the Kashgar gorge to Kokand, but Valikhanov did not dare to go to Kokand, where he could be recognized... And at that time, rumors spread again through Kashgar that a Russian agent had infiltrated the country with Musabay's caravan. It was said that he was hiding behind the City, in the pastures, among the servants of the caravan. One of the cunning beks rode through the pastures afterward, but did not find the Russian. Aksakal Nor-Magomet laughed at the suspicions of the native authorities and was ready to guarantee with his head for every member of the caravan...

But Valikhanov began to urge Musabay to return. The long nervous tension was taking its toll, and it was becoming increasingly difficult for him to play the carefree young reveler. He had long since packed the diaries, ancient Uyghur books, samples of handicrafts — including chekmen, mashru, timpay, daraya, and other woolen and paper materials... Now, the tragic story of Shlagintweit and the thought of the fate of his notes would not leave him in peace. The slightest carelessness and... everything he had done, Valikhanov, would fade into oblivion, and Kashgaria would once again be a blank spot for world science...

New information about the suspicious actions of Hodja Valikhan distracted the Chinese and local beks, and they stopped searching for the Russian agent: a more real danger loomed over the city... Kashgar lived a tense life full of anxious anticipation during those days. In the city police, the dynza, they gathered spears and darts, the guards at the gates were reinforced, and again, with the onset of darkness, horse patrols clattered through the quiet streets.

...Spring began. The city ponds thawed, and water was let into the irrigation ditches. At the end of February, pies stuffed with green sprouts were already being sold at the market... After long delays, on March 7, 1859, the caravan set out from Kashgar.

Valikhanov and his companions faced many trials on the return journey. They learned in the city that they were being closely followed by spies sent by large Kyrgyz clans, that the wealth of the caravan was the subject of the most fantastic rumors, and all lovers of easy profit were eagerly awaiting the caravan's appearance in their territories. They fully experienced the so-called "Eastern hospitality," so celebrated in legends and books: Kyrgyz clan leaders forcibly drove them into their auls, served them two thin rams for dinner, and in the morning demanded expensive gifts, and if the gifts seemed small to them, they simply robbed the caravan.

They faced their final trial already in the Issyk-Kul basin when they were passing through the Zaukin gorge. There, the formidable Kyrgyz clan leader Turgeldy stopped the caravan. He had heard of Valikhanov's presence in the caravan, and one of the Kyrgyz recognized and revealed him. Turgeldy had become brazen: he threatened to send Valikhanov to Kokand and demanded a huge ransom. Fortunately, a Russian military detachment sent to meet the caravan arrived in time, and Turgeldy retreated into the mountains, not risking to worsen relations with the Russians...

For the first time that night, Valikhanov fell asleep completely peacefully. The road ahead led through familiar places. The blue Issyk-Kul, shrouded in a delicate azure haze, was left behind, and ahead loomed the stone barrows of San-Tash, said to have been erected by Timur's warriors...

And again, Chokan Valikhanov pondered the past of this land, its present and future...

Yes, the history of the peoples of Central Asia is complex and tangled. Valikhanov had managed to read only a tiny page from this vast book, which had been written over centuries, a book that no one had yet looked into...

What does Central Asia represent? — Valikhanov asked himself. Slowly but surely, it is turning into a desert with ruins of cities, abandoned aqueducts, canals, wells; ancient oases are being buried by sands, and in place of gardens, only black saxauls stretch their gnarled, sun-dried branches toward the sun. On the ruins of once prosperous cities now stand miserable mud huts, and ignorant people, beaten to idiocy by religious and monarchical despotism, live in them. They are ruled by insignificant little men like Hodja Valikhan, who imagine themselves to be all-powerful rulers, capricious, whimsical, destroying thousands of innocent people without trial or investigation, building pyramids of human heads or barrows of stones — mute witnesses to their bloody atrocities...

With bitterness, Valikhanov thought that in Bukhara, Khiva, Kokand, which were once rich and enlightened cities, poverty and ignorance now reign. The priceless libraries of Samarkand, Tashkent, Fergana, Khiva, Bukhara, the observatory in Samarkand were destroyed by the Mohammedan Inquisition, which condemned any knowledge except religious knowledge. Many monuments of the great cultures of the past were erased from the face of the earth as evidence of the sinful struggle of Man against the creativity of Allah. Only mosques, madrasahs, and the tombs of Mohammedan saints, only kenekhanes — bedbug-infested pits for confinement, only prisons and the Munar tower, from which criminals are thrown, preserved due to their "good" purpose...

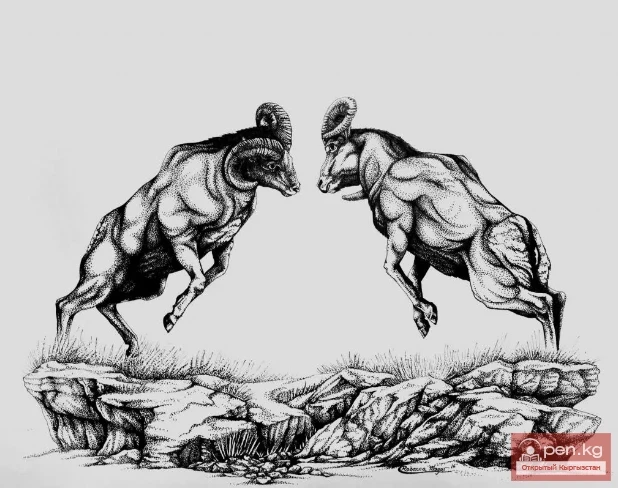

The Central Asian rulers do not write poetry or memoirs, do not compile astronomical tables, as their ancestors did. Instead, every day they head solemn processions to mosques and humbly converse with mullahs, and upon returning home, they go to the arena to enjoy the fight of trained rams. The fierce animals fight until one of them has its skull cracked...

Chokan Valikhanov thought about the future of Central Asia. It appeared to him vaguely — he saw a people living freely, not dependent on the whims of usurpers, saw people unafraid to walk with their heads held high and not trembling before Muslim dogmatists, saw farmers and artisans working for themselves.

Chokan Valikhanov did not know how the peoples of Central Asia would achieve a prosperous free life, who would be able to extinguish national and religious strife. But one thing Chokan Valikhanov was firmly convinced of: the future of Central Asia is inextricably linked to the future of Russia... A thousand times his famous great-grandfather Khan Ablai was right to accept Russian citizenship along with his people... Valikhanov did not like everything about the relationship between Russians and Kazakhs, but he believed that these relations could be improved, made equal for both Russians and Kazakhs, and he mentally vowed to dedicate his whole life to the struggle for a better future for the peoples of Central Asia...

He kept this vow and remained in the memory of descendants not only as a brave traveler, an explorer of Kashgaria, but also as an enlightened democrat who fought against the arbitrariness of the tsarist administration and local wealthy individuals, whose interests, in his words, were always hostile to the interests of the people...

This concludes the story of Chokan Chingisovich Valikhanov's journey through Tian Shan and Kashgaria — he safely reached the Russian military post Verny, and then returned to Omsk, — but the story of Valikhanov's life and activities does not end here.

His report on the trip to Kashgaria so interested the St. Petersburg residents that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs sent him an urgent summons. Valikhanov's dream came true: he was able to go to the city he had long dreamed of.

He rushed along the winter roads and thought of the distant city, the university, the geographical society, and the upcoming meeting with Semenov.

And all this came true: in early 1860, Valikhanov arrived in St. Petersburg and plunged headlong into a new, unusual life for him. Who could complain about the inattention of the St. Petersburg residents! Both geographers and ethnographers-orientalists, military men, and diplomats rushed to get acquainted with the young traveler, to learn more about the results of his research. And Peter Petrovich Semenov, a practical man of broad and sober mind, immediately suggested that Valikhanov write detailed essays about Kashgar, with the aim of publishing them in the publications of the Russian Geographical Society.

But what caused such heightened interest in the young Kazakh? There were many reasons for this. In his works, and primarily in those such as "On the State of Altyshar, or the Six Eastern Cities of the Chinese Province of Nanlu (Little Bukhara) in 1858-1859," "Essays on Dzhungaria," Valikhanov was the first to talk about the state structure of Altyshar, the political situation in this province bordering Russia, the class composition of the population, the economy and nature, and everyday life; he told about the atrocities of the bloody hodja Valikhan, about the fate of the German traveler Adolf Shlagintweit. Before him, no one knew anything about this. He erased another "white spot" on the geographical map of the world: Kashgaria ceased to be a mystery for European science.

But the significance of Chokan Valikhanov's feat lies not only in this: the proverb is true that the hardest step is the first. And Chokan Valikhanov took the first step in the study of Central Asia by Russian geographers.

A little time will pass, and a close friend of Valikhanov from the Omsk Cadet Corps, Grigory Potanin, will head to Central Asia, another Russian traveler — Pevtsov will visit Kashgaria and tell about others who came after Hodja Valikhan, usurpers, about the new sufferings of hardworking Kashgarians. A glorious page in the history of Russian research in Asia will be written by the famous Przhevalsky: his ashes still rest on the high bank of Lake Issyk-Kul.

Valikhanov was a true "treasure" for science in another sense as well. Try to imagine yourself in the place of an orientalist-ethnographer trying to study illiterate Central Asian nomads, their everyday life, culture — a task more than complicated. But Valikhanov, a Kazakh himself, who knew the life of the steppe dwellers, their folklore, their religion, could give a lot to science.

The months that Chokan Valikhanov spent in St. Petersburg must have been the happiest of his life; he studied, worked, communicated with outstanding scientists, met Dostoevsky, got acquainted with his favorite poets Polonsky and Maikov, read "Sovremennik" by Chernyshevsky and "Kolokol" by Herzen, responding vividly to everything progressive, to everything calling forward, to progress. But illness — tuberculosis — was undermining the strength of the young scholar, and in the spring of 1861, he was forced to leave St. Petersburg for his native steppes, taking with him unfinished manuscripts, sketches, still dreaming of scientific work. Unfortunately, Valikhanov did not manage to realize many of his ideas; he died at the age of thirty, just seven years after returning from Kashgar...

Chokan Valikhanov in Kashgar. Part 5